Lucy Lawless. If you don’t know who this Kiwi screen legend is, shame on you! The woman repeatedly got to smack Kevin Sorbo on television and became an ideal woman for a generation of straight and queer folks via her role as Xena: Warrior Princess. Lawless is an industry professional with years of experience and acting credits.

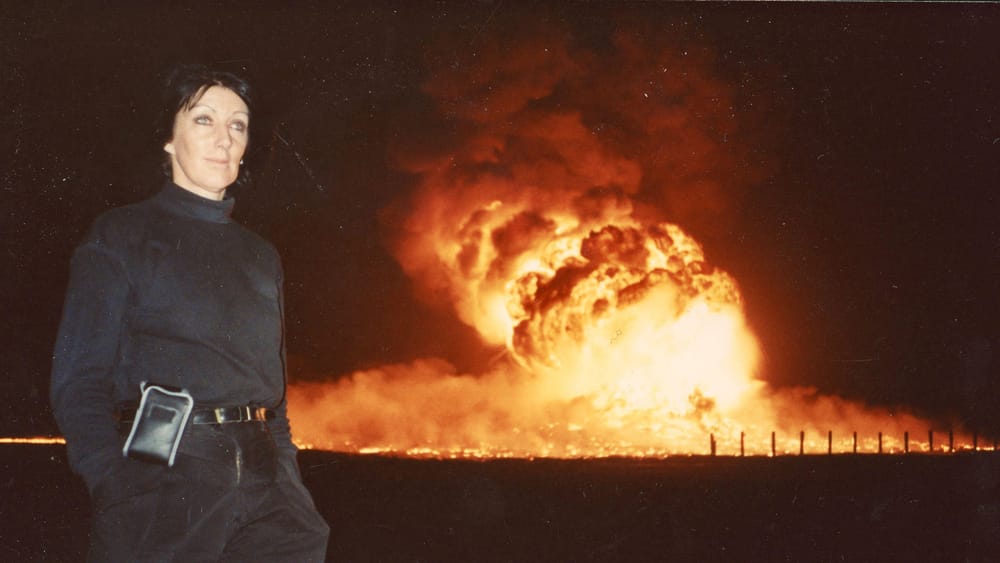

In her directorial debut, the documentary Never Look Away about the incredibly complex war correspondent, Margaret Moth, Lucy captures the spirit of another warrior princess. A kick arse camera commando shining her camera light on a world in conflict. Margaret Moth was uncompromising, bold, reckless, and dangerous. Never Look Away is a testament, not a hagiography.

Nadine Whitney talks to Lucy Lawless about a woman who changed the way people saw the world through her news footage and the multiple prices she paid personally and professionally by marching into war.

Nadine and Lucy begin the interview exchanging Australian and Kiwi greetings. From Kia Ora, babe, to G’day, mate. Lucy is infectious with her energy.

Margaret Moth. I didn't even know she existed until you brought her on to my radar what brought her onto yours?

Lucy Lawless: I got this email, and I was immediately jettisoned back to a news report I saw in New Zealand that one of our own journalists had been shot in Sarajevo. A camerawoman for CNN. And everything that I knew about Margaret must have been from that moment. I don’t know what possessed me. I wrote back straight away making all these crazy promises. I was terrified someone else would get it before me. I was like “Yes! I’ll find the money! I’ll hire the producers! It HAS to be made!” I was thinking I have to be the one to make it. I didn’t say that, of course. But I was thinking, “It HAS to be me.”

I pushed send and went, “Holy shit, Lucy! You’ve never done anything like this before. What are you talking about?” (Lucy cackles). I realised that I was in it too deep now so I can only go forward. I swear to God it was never a plan for me to direct. I guess I didn’t think I was capable of directing.

You’ve proven yourself wrong about that, haven’t you?

LL: Yeah! I’m so delighted I was wrong. I have never been so delighted to be wrong.

The documentary is so important right now because it’s tapping into not only the real-world events playing out on our screens in some of the same political and regional war zones, but also because it’s joining in with a cultural conversation happening in both documentary and fictional filmmaking. On the fictional side there are films such as Civil War, September 5, and Lee the Kate Winslet led biopic about pioneering photojournalist Lee Miller. The lives of people who throw themselves headfirst into conflicts to bear witness for the world are being examined.

LL: Yes! Truth telling is a big part of the conversation right now. And women on the frontlines.

How did you go about getting the archive together? That must have been a massive challenge considering all the places Moth travelled and reported on.

LL: Ooh. That was tricky. Oh my god, that was really hard because CNN were as willing to be as helpful as they could. However, the problem is that in those days (the early 1990s) all the news footage was shot on massive Betamax tapes and was edited in the field and the finished product would be sent back by satellite to Atlanta. Then the tapes would either be taped over or destroyed. So, there was no way to be entirely sure whose work or footage it was. Plus, a lot of Margaret’s work had just gone. There was no crediting for camera people back then so cross referencing was difficult.

What we did is we went back to conflicts I knew she was at by checking her press passes, passports, and had been told about anecdotally. There is likely a lot of other people’s work in the final product. But that’s the ‘cost’ of making a film. I’m trying to take the audience on a journey and also entertain. I’m not a journalist. I bend the rules a little for effect.

Margaret Moth is a fascinating and paradoxical woman. It’s impossible not to be interested in her psychology. When you were reaching out to speak to people about her, especially other women in the film like Christiane Amanpour, how did you gauge how they wanted to talk about Margaret? There are quite a few men talking about her – importantly her best friend and colleague, Joe Duran. But it feels like there are parts not being said.

LL: A lot of people wouldn’t talk about Margaret and I’m not entirely sure why. Maybe they didn’t particularly like her. She was not always agreeable. Or they perhaps thought I was just going to make a hagiography. With the journalists I had to earn their trust. I had to assure them I wasn’t making a film sanctifying Margaret. I’m interested in humanity and our warts and all. I believe our flaws connect us. I got some great help from dear colleagues of hers. But you have to earn people’s trust, and you have to keep it.

I think anyone who sees the documentary can tell that Margaret was not the easiest person in the world to get on with. She also wasn’t a one-dimensional human. The way people speak about her there are a lot of repeated adjectives. “Gutsy, fearless, terrifying, reckless, indefatigable.” But there are people such as Stefanos Kotsonis and Joe Duran saying she was also vulnerable and lonely, and predominantly she cared about the people she was filming.

LL: She was sometimes mean to people too. Vulnerable and mean.

Margaret stood on a roof waiting for the IDF to send a missile at the building she was on with her camera on her shoulder. Everyone else was scrambling downstairs in panic and she stood defiant. How can the ‘average’ person unpack doing something like that?

LL: I feel like once death had come for her after being sniped in the face in Sarajevo, there was an element in her mind which responded, “If death comes for me again, I’m going to film it.” It’s like an Ellen Ripley moment from Aliens where she says, “Come on, you bitch!” I think she believed she was taking calculated risks. I think she thought they wouldn’t get her. But there is no way to truly know that.

There aren’t many ways to know what life has in store for us. But very few of us go out and bear witness and share witness. It’s an incredible thing to have done. Even with the complexity of her character, her work needs recognition despite the fact that you can’t cover up the difficult parts of who she was. Her relationships with very young men – seventeen-year-old Jeff Russi for example.

LL: Her relationship with Jeff wasn’t her first with someone that young. Part of what I felt was my deal with Margaret and her legacy was to be unsparingly non-judgmental about all of it. In that way, I kind of made it the audience’s problem. I’m putting it in your lap and now you have to deal with it. She’s thirty and she’s with someone who is seventeen.

It was interesting to see how different countries and cultures dealt with that kind of information. I’ve been in Europe, Canada, Australia, North America. All over the English-speaking world with the documentary. People react to it differently. Nevertheless, I wanted it to be non-judgmental because she was.

I realised from my acting that if I don’t put a spin on something, it’s like a character. You take it all the way to wanting to cry, but if you don’t cry and keep a lid on it, the audience cries for you. That’s the sweet spot. I want to basically give people pain. I want people to feel something for Margaret and for those in her orbit.

You can’t, in good conscience, make a real person unreal. Many of the people interviewed in the documentary attempt to explain how their minds began to react as war correspondents. The feeling of not knowing which chemicals were being fed into their brain via their body’s adrenal system. Is it dopamine? Is it adrenaline? Is it serotonin? Which impulse do they follow first? And what happens when someone is out of a war zone? Margaret looked for other (often illegal) highs. She had complex PTSD.

LL: I think she had PTSD from her childhood that was unexamined. That’s why she was able to live her life the way she did. She had shut certain doors. She wanted to be nothing like her New Zealand family. Her mother and her sisters had babies young, and everyone left home at fifteen and got married. Everybody got knocked up. Her mother didn’t want babies but kept getting pregnant. Margaret experienced a horrible legacy of abandonment.

Margaret shut the door on all of it. Changed her last name. Changed her look – going from a blonde to a dyed-black haired proto-punk. She said she couldn’t remember anything of her past at all. And let’s face it, we all love an amnesiac. So that’s where I started the story because it’s so ‘lean in.’ Then we follow up with a bloody rousing rendition of ‘Barracuda’ and some war footage, and then we’re off to races!

It’s very hard to get traction on a film about a non-famous person. So, I’m really grateful people are taking the time.

Making a film about someone like Margaret Moth is uncovering history. It’s putting women in the conversation around being active participants in global events. Margaret Moth’s camera is and was vital.

LL: Yes! We need this! We need her to be seen. Let’s make her famous.