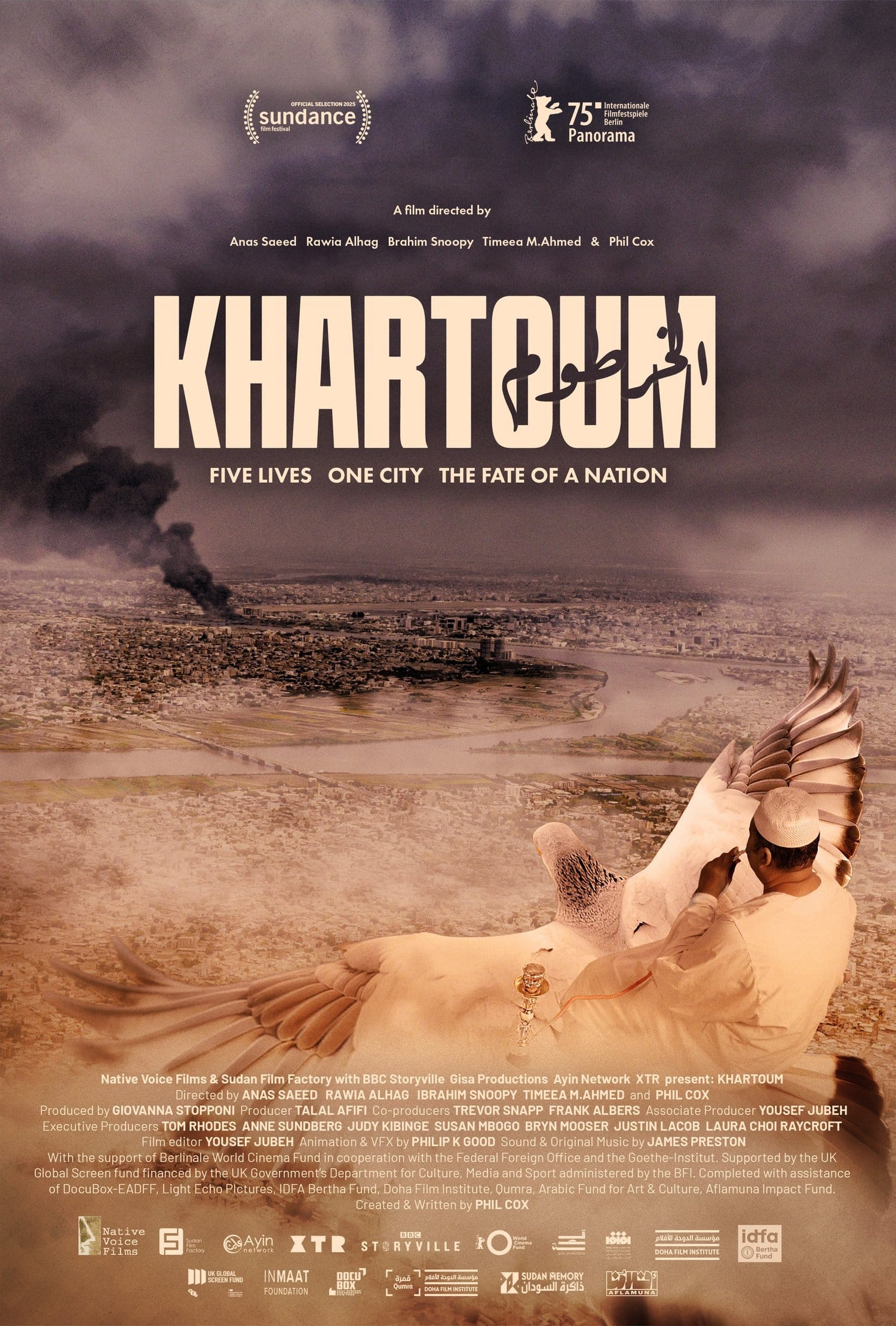

Image: Top L-R: Yousef Jubeh, Brahim Snoopy, Anas Saeed, Phil Cox; Bottom L-R: Giovanna Stopponi, Rawia Alhag, Timeea Mohamed Ahmed; Photo Copyright: Native Voice Films

Five lives. One city. The fate of a nation.

So goes the tagline for the stunning collaborative documentary Khartoum, which had its world premiere at the 2025 Sundance Film Festival. Khartoum sees four directors, Brahim Snoopy, Rawia Alhag, Timeea Mohamed Ahmed, and Anas Saeed, who come together as story custodians to amplify the stories of five participants, Lokain & Wilson, two young boys who navigate the streets of Khartoum, seeing a world that is different from the adults who run the city, all the while continually searching for an elusive lion that they are yet to see; Khadmallah, a tea vendor who talks with her patrons over cardamom coffee about their lives in Khartoum, all the while she dreams of starting her own business; Jawad, a Sufi Rastafarian resistance volunteer who patrols the streets of the city on his motorcycle, engaging in vital acts of protest for the existence of a civilian government; and finally, Majdi, a civil servant who engages in pigeon racing while dreaming of a great life for his son.

These five voices are supported tenderly by Snoopy, Rawia, Timeea, and Anas, who, as directors, each give space to hear stories of the Khartoum of the past, and each of their journeys as survivors of the war that broke out between the army and the Rapid Support Forces. This is a war that caused the upheaval and displacement of over eleven million people, with everyone involved in the production of Khartoum impacted by the war.

Filming on Khartoum began in 2022, commencing as a collaborative process between the Sudanese filmmakers, Phil Cox, a British writer/director, Yousef Jubeh, a Palestinian-Irish editor and associate producer, alongside the work of indie company Native Voice Films and Sudan Film Factory with Ayin Network. During the process of shooting, the war broke out, with the production shifting funds towards to ensuring that all involved in the film were able to escape to East Africa.

Once safe, the production considered an approach to continuing telling these stories which saw the utilisation of green screen reconstructions which allowed the participants to safely retell their stories, including powerful moments of ‘dream reversions’. While the narrative is one that emerges out of the impact of an ongoing war state, Khartoum is a film that honours Sudanese culture and community, embracing moments of joy, warmth, and positivity with sequences where participants dance between stories, or, more importantly, find moments of tenderness between each other, the directors, and the crew, as they embrace each other after retelling their stories.

Khartoum is an act of cinematic resistance. It is a filmic protest for the right for the lives and soul of a nation to continue living. It is a narrative driven by cinematic ingenuity and the need for stories about conflict are continued to be heard and shared across the globe. As Snoopy mentions in the below interview, Khartoum is not an act of reportage, but rather an emotion driven experience that lingers long after the credits have rolled.

Yes, again, this is an act of cinematic resistance, but more importantly, Khartoum is an act of community. It is a film that shows the strength, power, and enduring humanity that emerges from communities, and in the light in the resilient eyes of each of the participants and the directors, we are able to see the place of hope in their souls. You owe it to yourself to watch Khartoum and to hear their stories.

In the following interview with Brahim Snoopy, Rawia Alhag, Timeea Mohamed Ahmed, Anas Saeed, and Phil Cox, that role of community and the ethos behind Khartoum is discussed.

To read more about Khartoum and how to support the film, its participants, and the ongoing fight for free media in Sudan, visit the films website here.

Timeea and Snoopy assisted with translating during the interview. The transcript has been edited for clarity purposes.

I’d like to start our conversation by reading a quote on the Khartoum film website which reads: “This film represents our resistance to war and our belief in the Sudanese people to overcome.” Can you talk about the way that the art of cinema is an act of resistance in itself?

Brahim Snoopy: We've been for a long while resisting in many different forms in Sudan, going on the street, dodging bullets, getting almost killed. A lot of us, especially Anas who was on the front line, [were] documenting what the old regime was doing to the youth and all that. So, I think that cinema is the ultimate form to put all of these things in the one platform in a more thorough way, meaning that we don't want also to be traumatising people or recreating some kind of a bad memory, you know?

That's why on this film specifically we didn't want to do another reportage; you can always find the up-to-date information of what's happening in South Sudan, North Sudan, Kordofan, all these areas. We also wanted to let the world know what's happening in Sudan, but not in a very gory way [or a] very negative way, so we try to as much as possible to align the negative but also the positive side of war; it impacted people on a personal level and a community level and on a full country scale level, but also [we didn’t want to] forget about their dreams and ambitions. At the end of the day, we're human beings, right? So, we wanted to reflect what their inner hopes and dreams [are] right before war, during war and right now, after war, and I think cinema is the best platform to portray that.

People can see like two- three-minute [news] reports, but it never conveys the full internal feelings of people. We tried to digest that into five characters, and all these characters have like different layers in the community. Some of them didn't even see each other, because you'll be living in a specific bubble, and you wouldn't see what [is] right above your shoulder. We try to, as much as possible, portray all these different layers, not only for the world to know, but also us as Sudanese people to know each other so we can understand each other and prevent what's happening right now from happening again in the future.

Timeea Mohamed Ahmed: It's also a new way to tell the narrative. It's like people are fatigued with all the information they have from Sudan CNN reports or [other news agencies], it's like, ‘Okay, that's a new revelation of the story of Sudan.’ People could think about it in a different perspective and could feel it more than they just know it. That is what most of us would love to have as an impact from the film to the international audience, and specifically in Sundance.

One of the things which I really appreciate about the movie is the use of song and dance in between the stories. We're getting to see a slice of Sudanese culture that we rarely get to see amidst the news reports of the war. We rarely get to see Sudanese culture in a vibrant way. Can you talk about the importance of being able to see that kind of joy – the smiling, the dancing – in the face of this kind of difficulty?

Anas Saeed: It is very important to also reflect the Sudanese community [on screen], the cultural side of Sudan, not just the war side, also the diversity, the revolution, and the resistance, that we had for so many years. It started many years ago, but in 2018 it started to accumulate into what happened now. So, it’s great to reflect on all of that. It’s also in one big mix between archive, recreating all of these scenes, and for all of that to reflect Sudanese culture and community.

Phil Cox: I’ll just come in briefly to answer the first question. I am an outsider on this. The simple act of these filmmakers coming together is an act of resistance, because Sudan has always been fuelled by ethnic division and separation. The British presence has left a strong legacy about division; Arab African, ethnicity against ethnicity, class against class. All the people behind the camera represent such a different ethnic background, gender approach and that in itself is a huge statement.

The people in front of the camera, the stories that the directors chose, also represent a massive diversity in modern Sudan. The bureaucrat would never meet the street boys, it would be untouchable. The stories behind the camera and in front of the camera, the fact of it is this is a kind of resistance against the constant division and separation which has fuelled war and division in society, which we all face globally with people dividing us.

I think, regarding the question about the culture and art, the film started before the war, and the filmmakers were all making a cinematic poem about Khartoum. That was so vibrant and such a part of it that they all stated, like Snoopy said, that they didn't want this to be a reportage, but an experience. The film needed to be a kind of ethereal sensory experience, not just information. They were quite ambitious, but we didn't know if it was gonna work or not, but that was their thing, that the film should be felt, not just inform.

You can feel that it is a mixture of pain, sadness, but also joy. I know the path to getting to now, to screening at Sundance is a long one, and I know that you've each gone through your own personal journey of escaping Sudan to get to safety. As safely as we can talk about this, knowing that you had already shot part of the film, and that you were going to have to escape war, then, to continue telling this story in some capacity, while all this turmoil is taking place, what was that experience like for you?

Rawia Alhag: We started shooting before the war with big hopes and dreams for the film and in a way that we would love to document and reflect the city that we all love the most, Khartoum, which represents all of Sudan. After the war, everyone was separated. We lost communication with each other and for some participants for more than five months. We were lost for [some] times, and then we decided that we can reunite and continue producing the film.

All of the team decided that we want to pursue with the film. We need to show our stories to the world. When we communicated with the participants regarding this matter, they said, ‘Yes, we want to continue producing and we want to keep making the film.’ Then we decided that we can go to Kenya to keep creating the film.

Anas Saeed: It affected us all in a bad way, for the participants and the team. As Rawia said, we didn’t know if we could continue or not. We had a bad time, but after that, we did it.

Phil Cox: Obviously, we lost everything, and all the film funds were used to help the participants evacuate. Then when everyone arrived in Kenya, it wasn't all happy and smiling. Then the priority was about mental health support and housing and the film took a real back step. The way we work, or the way I work, is that there's the film, and then there's us as the community of filmmakers, so the film really stopped completely while everyone addressed themselves. People have been through trauma, so we had to address that first in a way. Then, I think with that time and space, they all thought, ‘Well, everyone's lost everything. What can we do?’ And the film became this act of resistance, in a way. It was a big space that the producers gave the team to be able to do that.

Brahim Snoopy: Also, part of the journey of this film was also us all being together and living together, that was part of the healing process, because the participants have seen a lot of gory scenes in Khartoum. Once we brought them here, we had all been living together for a few months, and that was part of the healing. We're trying to switch the damage that's in their head with beautiful images. We were going around Nairobi seeing beautiful places, always going together, eating together, living together in the same apartment, so we can all ease the impact of war [on each other’s mind.]

We, the directors, came a few months earlier because we were trying to figure out what the next plan but once that was figured out, then the participants came. We had to make sure that they healed. We can't heal them 100% but at least just to ease the impact of war on them.

Phil Cox: I think the film was a cathartic process for the people behind the camera and in front. What Snoopy says is really important in that when these participants came to do their reconstructions, and they decided which bits they would choose, the directors before that had in front of the participants themselves reconstructed or re-performed their own moments.

I could never have made this film, because I don't have that power of parity in the sense of trauma, both in front and behind the scenes. The directors gave themselves, and the participants saw that, and then came on board with them. That was a huge thing for why you see the participants so giving of themselves on the green screen because the directors did it themselves, but you don't see that in the film.

It feels vitally important that we get to see you hugging the participants. It is a healing process, both off screen and on screen that we get to see that that it is a supportive healing process.

The young boys in the film, Lokain and Wilson, talk about the world that kids exist in that adults cannot see. You're all adults listening to their story, and I'm curious what you learned from them in your interactions with Lokain and Wilson? How has seeing the world through their eyes changed you?

Anas Saeed: It was very hard on the kids to go through war and to see all of the imagery of people getting killed. Also, at some point they were used to do labour for one of the sites, and that had a very bad impact on the kids. They were used also in many different, abusive way, such as cleaning cars. There was a specific strategy that one of the sides was doing which was to fill the cars with mud so that the drone doesn't couldn't detect which side it was. We were saddened to see this happen to them. They didn't have any hand in all of this. Maybe Rawia, you can explain a bit more, because it's their story.

Rawia Alhag: Before and after the war, everything bad that happened to Lokain and Wilson was from the adults. In the healing and support processes, before even filming, we were not trying to change [that] idea, but trying to give them more ideas about what elder people can also do. They can be also good people, like maybe us, and they can help, they can support. We can be friends.

And now, Lokain and Wilson are my kids. I am their guardian.

That's wonderful to hear. Will they also hopefully be able to get to see a lion?

Phil Cox: They’re the naughtiest boys you'll ever meet right at the moment, Andrew. I think they've impacted the whole team. The transition from when they arrived to now has a lot to do with Rawia who found them before the war. I think it's just about the commitment to the people you work with in front of your camera that everyone has shown in this film that has just been really exceptional. Rawia is their guardian in Nairobi, and the whole team has been supporting them, and the production have been supporting their education. They'll all be looking after us soon enough,

As the youth always do. They do a very good job of it as well when they're given great support and guidance, like you all have given them.

I want to close by asking about the mental safety that you have in place for each other when you're going through this process of now doing press for your film and sharing it with the world. How do you stay mentally safe when entering a discussion like the one we’ve just had?

Anas Saeed & Brahim Snoopy: There's a saying in Sudan that once you see other people's issues, your issue would be the least painful one. So, in the sense that there are other people who are going through way more difficult stuff than what we're going through. I think we're lucky right now to be impacted by work, but not that as much as other people who are still living in danger zones and going through massive abuse and rape and killing to the point where they're committing suicide.

So, us being here today, with a great team all together, is a healing process which keeps us all sane. I think that part of all of this success is that we have great people, a great team, producers, directors, even editors. We're not even working together anymore. We're just one big family. We're looking out for each other, even the participants. Like the tea lady, you always go to her, you support her, drink tea, and have these discussions, a couple of laughs over here and over there. And I think all of this together, when you look at it from a distance, it can be all healing, right? And that eases the impact of war and the impact of the issues that we went through.

Sometimes we look at what we went through and we just laugh at the situation. I know that it's not something to laugh about, but it's also because we're now here altogether, we just ease the pain.

Timeea Mohamed Ahmed: If I may also add to this, as Snoopy said, it is a collaborative sense of a family. On a very personal level, we lived together for a few months. This production and the creation of film, and with the amazing producers, we can say that the path of our lives almost change, even for most of the participants. We are now in other places that most of us [did] not expect to be at. We're now living other lives. For me especially, I feel very privileged towards what I have in life and where I am in life now.

As Anassaid, when I'm comparing that to all other Sudanese people, I feel more of liability than it's a trauma. I feel that I have a weight, that I have to reflect the Sudan cause and what's happening to the people on the ground now; there is hunger, there is displacement, there are border issues. We have way more issues to worry about for other people than us in the moment, and that we need to feel like we're obligated to speak. That's the least what we can do with this film and the impact campaign that will come with it, that will be led by Giovanna Stopponi and Tala Afifi.

Rawia Alhag: Anas, Timeea, and I were the last people from the crew, from the directing team, who went out of Sudan to Kenya to continue producing. What felt the most important for me is that we went together in the same flight, in the same movement, and that meant a lot to me. Once we were in Nairobi, we discussed and told our personal stories about the world which was very similar to each other, and we felt each other, and that also felt like a healing phase of the production.