This review contains spoilers for Vulcanizadora and Buzzard.

Vulcanizadora is a gnarly word, one that–out of context–suggests a fury of rage and violence at the centre of a chaos of noise, conjuring associations with Vikings or death metal music. Its true meaning is something quite different, describing someone who ‘treats crude rubber with sulphur, exposing it to high temperatures to increase its durability and elasticity.’ For Joel Potrykus, Vulcanizadora becomes an apt word to title his follow up to the 2014 slacker dramedy Buzzard, with the filmmaker subverting audience expectations by skewing away from the notion of a grotesque flick into something of a depression-laden trek in the woods, testing his characters durability in the process.

In Buzzard, Marty was a temp worker who thought he found a way to game the system by cashing cheques returned to the company he works at, signing them over to himself for small gains. Burge imbued a youthful Marty with a deep level of naivety and ignorance, presenting a teen in a man’s body who is still learning the rules of the world and thinks he can be king for a day, or maybe even a week. A central scene in Buzzard sees Marty sitting in a white robe, devouring a plate of spaghetti as he sits in the low-class luxury of a cheap hotel room paid for by his ill-gotten gains. With a grin on his face, Marty shovels spoonfuls of pasta into his gob, munching it down with open chews, sauce dripping onto his chest, all the while watching mindless TV. This is the life; no responsibility, no accountability.

Vulcanizadora picks up with Buzzard’s main characters Martin Jackitansky (Joshua Burge) and Derek (Joel Potrykus) a decade after their office work exploits. Potrykus slowly ekes out information in Vulcanizadora, asking us to follow Marty and Derek on a surreptitious journey through the Michigan forest. Marty is mostly silent, an unspoken end goal as the guiding force in his mind, all the while Derek provides a running commentary of nothingness, liberally using ‘oh yeah’ and ‘dude’ like connecting words, seemingly just happy enough to chill with his mate as they walk along, throwing out the occasional ‘this’ll be great’ like a mantra, as if he’s trying to will a good time into existence.

Vulcanizadora has been marketed as a horror-comedy, and while I’ll dismantle those genre-definitions a bit later on, it is fair to say that in the opening half hour, Derek exists almost solely as the films comedic offering. Derek is dressed in camo-attire, replete with a hiking backpack and a neck-covered hat to keep his balding head protected from the sun. He looks comically out of touch with his surroundings, as if he's long talked about being one with nature, but in reality he's never left the carpark. His presence is a comedically defensive one, set in place as a distraction from the gravity of the end goal of their hike.

The Marty at the end of Buzzard is in a state of vagrancy, having assaulted a banker with a homemade Freddy Krueger Nintendo power glove after the police are called after trying to cash stolen cheques. The Marty we meet in Vulcanizadora has had his mind scraped away by the scalpel of time and a stint in prison; a decade of baggage hangs under his eyes, a result of the endless running from petty crimes. To manhandle a square analogy into a round hole, if the Marty we met in Buzzard was a flexible, reactive slice of crude rubber, bending a system to fit his existence, then the Marty we see here has had his durability and elasticity pushed to the limit, a person fraying at the seams, the morality of his soul having finally caught up to him. Potrykus later makes that analogy explicit when we discover that Marty is facing trial for burning down a tyre store, providing some reason why he and Derek are on a journey to nowhere. The lessons of life don’t linger long in Marty’s mind it seems.

These are the slackers of the nineties evolved into feckless and focus free adults, inert in their roles in life, as useless and unmemorable as the last Gatorade you’ll ever drink. But Potrykus ensures that we do remember them and that their existence lingers in our mind, just as much as he forces us to consider the feel of the last drink you'll ever have or the taste of the final cake you'll ever eat. They may be disposable food, but for someone, they might be the last meal they'll ever eat. And that must mean something, as must as Derek and Marty do at least.

The opening of Vulcanizadora carries an odd level of comfort to it. Derek and Marty engage in frivolous activities on their journey through the woods: repeatedly hitting a tree with sticks–‘this one’s a good one Marty,’ Derek exclaims with absolute joy, holding up an admittedly good looking stick–, discovering a weathered plastic bag of ancient porno mags left behind by an acquaintance, reconnecting with a boyish giddiness over the sight of consensual nudity, playing ‘cool’ music on a Discman attached to PC speakers in the middle of the night, mindless chatter about nothing just to fill the void of time while existence peters out. Even Derek’s attempt to recreate a Faces of Death video with Marty shooting a bottle rocket at his face carries a perverse level of charm to it.

While we become comfortable to the mateship of Derek and Marty, Potrykus also toys with our patience. The two guys are loud eaters, crunching chip pack and moaning with delight over the taste, crinkling the packet in their hands as they anticipate cramming the next handful in their mouth. They repeat lines of meaningless dialogue like an annoying parrot. They're messy, disorganised men who are ill prepared for a night in the woods. If they were Australian, we'd say they could barely organise a piss up in a brewery or couldn't find a root in a brothel. But, even with their annoyances, there’s something oddly alluring about seeing two guys killing time before time kills them.

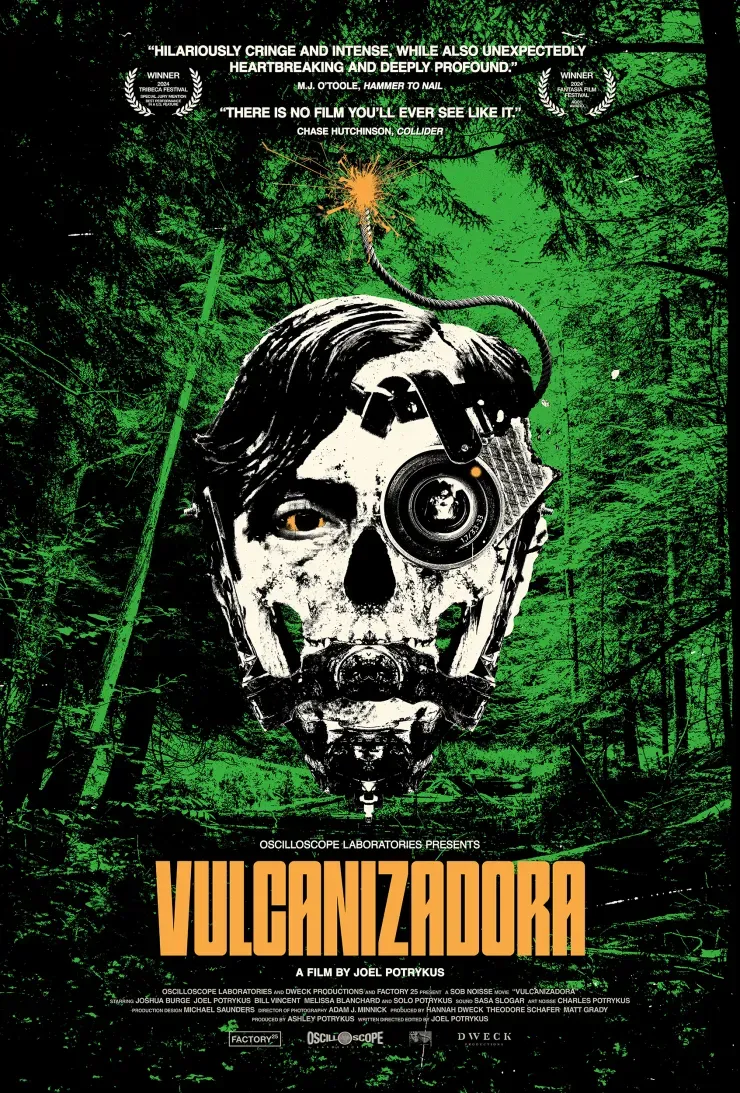

Which brings me back to the title of Vulcanizadora, and by virtue, the poster for the film; in unison, they suggest a grotesque, heavy metal flick, gnarly, obscene, gruesome, like caked in blood under fingernails. The poster is akin to something you’d expect to see on the cover of a Faces of Death video, one that you’ve smuggled into your bedroom to watch with stoned mates in between rounds of Smash TV on the NES, collectively leaning into the hope of seeing some poor sod getting mangled to pieces by some harbinger of death and destruction, a train, a high rise fall, a stampede of bulls, or maybe a home-made metal contraption that is designed to blast a hole in your head from the brute force of a store bought firework.

The promise of something forbidden has been amplified by Vulcanizadora’s presence at film festivals, often playing in horror friendly sessions, like its 11:45pm run at the Melbourne International Film Festival which caused the film to garner polarising reactions from audience members. An offering of reactions saw one Letterboxd user give the film a solitary star, saying ‘I stayed up past 1am for this…? […] My tolerance for literal grown-ass middle-aged men behaving like pathetic little children in the woods for 45 minutes has its limits.’, while another user praised the film with a four-star rating, saying ‘Really liked the first half, the fuck around camping trip slowly taking a darker edge until its in full-on horror mode.’

For that user, NotASexyVamp (chuck them a follow on Letterboxd, they write great reviews), the horror of the piece is the ‘empty sadness of these two men’s lives.’ Derek and Marty call each other best friends, but they talk about nothing of substance, filling the air with grunts and slang, skirting around the situation at hand and avoiding any kind of deep discussion. When Derek probes about Marty’s time in prison, he can’t help but lean into a childish mindset that prison life would be easy–‘I’d just get ripped’–or that he’d have seen countless naked men in the showers. It’s juvenile and yeah, it’s a little bit funny, but it’s mostly pathetic and sad. While Derek might see this as him being there for Marty, as an act of easing his pain, in reality he’s reduced the situation to a bit.

Given the lack of depth to their chats, I can only imagine how awkward the conversation between Marty and Derek would have been about Marty’s request to head to the shores of Lake Michigan, strap a metal mask to their heads, and murder each other in a suicide pact by blowing off their faces, having filmed it all on a Mini-DV camera for some poor soul to discover. I feel Derek would respond with a beat of silence followed by a ‘ride or die’ remark of sorts.

So, what of that horror in Vulcanizadora then? Is it the explicit horror of the splintered face of someone who ate a firework, their teeth in splinters, their jaw asunder? Or is it the pain of existence and the absolute, unceasing sadness of depression? Or, is the horror about the insurmountable fear one person feels about the possibility of going back to prison so he instead of facing a judge, he convinces his ‘best friend’ to join a suicide pact with him? A best friend who, just like Marty, needs some kind of guidance, understanding, and support to be a better person and to live with society, rather than against it. A third act reveal about the legal repercussions for Marty’s tyre burning bonanza adds a late slice of cruel comedy to the film, causing nauseating levels of uncomfortable humour to rise.

This, to me, is the horror of Vulcanizadora, and by extension, Buzzard. Two men perpetuating generations of shattered masculinity that have been haphazardly patched up by failing systems held together with Clag glue made from hundred-year-old horses. It just doesn’t stick. Again, the cover and title of Vulcanizadora suggests something forbidden, something taboo, but if we collectively dig out that caked blood and grime, then we’ll see that the forbidden thing is the way we talk about men’s health and the structure’s we need to put in place to stop the myriad of problems spiralling out from broken men. To me, that’s horror.

Seeing the lack of significant growth for either character between films is a sad point - one has grown inwards, the other treats their trudge to terminality as if it's a minor camping experience, all the while still attempting to show his mate how cool he might be. These moments are amusing, but they're also so pathetic and dispiriting that I couldn't help but shed a tear for these wayward men. There’s a line in Buzzard that acts like a message from the past to the present: ‘They don’t even know I’m gone.’ Taken out of context, it carries a weight when applied to Derek and Marty in Vulcanizadora. They have nothing. They are nothing. They will always be nothing. Take them out of existence and you'd barely notice they were ever there at all. That is, until a broken body is unearthed.

And maybe that’s the most brilliant thing about Potrykus’ film; he squirrels the promise of gore and violence and, most importantly, like Faces of Death, a body, into a film about depression, anxiety, despair, and sadness, just so those gorehounds, those violence fiends, those people just like me who see a title like Vulcanizadora and then see the poster, and say ‘yeah, I want to see some messed up shit,’ find themselves hollowed out by the time credits role. And when you have a Saw-like head trap device or someone who has made a Freddy Krueger glove out of a failed Nintendo device, you're understanably drawn into their machinations, adding to the morbid allure of seeing what they might do to a human body.

But Potrykus embeds the truth of these men so deeply in his script, one written and built on genuine fears: the responsibility of being a father, the guilt of existence, the remorse of making mistakes. While these are aspects that plague all of us, Marty and Derek aren't exactly the kinds of men who engage in deep discussions about their mental states, that is, until they're on the precipice of deciding their own fates.

When Marty and Derek talk about what hell might be like, they resolve that instead of eternal flames and pain and torture, that it would being anxious and sad and nervous forever. That’s Potrykus showing us true, genuine horror. The horror of being alone. The horror of being trapped with your thoughts and your feelings and waiting and hoping for the repercussion of your actions, but instead, you’re left with that sense of anxious anticipation of what's to come from the result of your actions. It's the sense of knowing you’ve done wrong but have not, and maybe will never be, freed from that guilt or shame by way of retribution.

Amplifying that unsettling tone is the way Potrykus underscores Vulcanizadora with an operatic soundscape, making this horror experience feel like the cinematic depiction of sad bastard music for the slacker generation. While the music is grand and glorious, the film it's scoring is discordant and lacks melody, unearthing a tune that rattles around in your mind like marbles bashing against each other, struggling to find the exit point that'll free them from their plight.

When I started writing my notes for Vulcanizadora, I wanted to critique and slam my fellow critics for highlighting the comedy or horror of the film. I said to myself that this is not what kind of film this is. I wanted to shout and say, how can you find this kind of pain funny? I wanted to rail against the notion of slamming a film like this into the genre pigeonhole of being a ‘comedy-horror’ film. When you say that, people expect a Scream or a Cabin in the Woods. They don’t expect this. I wanted to condemn those that called this a bleak buddy comedy or a morbid laugh fest, as if it diminished the sadness of the film.

Or, more significantly, as if it diminished my sadness. There's something truly absurd about having viewed two films released* in the last year that I feel reflect my own experiences, and then to have both end with main characters walking into waters, never to return; and it’s taken me more than a moment to disconnect myself from the audience reaction of the film.

I wrote notes pointing at the sadness of men, notes about why stories about men's mental health matter. I was ready to ride at dawn to fight for stories about cisgender white dudes. Yes, they matter, but spending thousands of words defending them? That's not exactly compelling reading.**

But, I did laugh at Vulcanizadora, and I am horrified by it. As I reflect on it, I find more situations to laugh at. So much so that my understanding of what comedy and horror is has been shifted. I laughed as I cried during Derek's annoying antics; he eats with his mouth open, chips falling down his shirt. He has no concept of an internal thought. He is so abrasive and it's so hard to find an entry point to care for him, that it's a testament to Potrykus performance that we do actually have sympathy for Derek.

Then there's the horror of Marty's existence which I've already detailed. What I haven't fully explored is the brilliance and depth of Joshua Burge’s performance, one that feels as if he's been keeping Marty alive off screen in between films. Burge is heavy here, desolate and hollowed out. There a looks he gives here when he has to spell out his surname, as if he's been here so many times before and he's so tired, so so tired of it. That look lingers in my mind, flashing across the darkness of my eyelids when I blink. Despair has rarely been captured like this on screen.

Despair is a constant with fellow filmmaker Kelly Reichardt, who has so keenly explored that state of mind in Wendy and Lucy and Meek's Cutoff. Yet, it's her earlier film Old Joy that stands as a tonal template for Vulcanizadora. Those men are differently cultured, having grown up on literature and folk music, they know how to salve their searing minds. There's a mood and a vibe in Reichardt’s work that is echoed in Vulcanizadora, a vibe that's also realised in its backwater cousin, Robert Machoian’s The Integrity of Joseph Chambers. This unsung gem is a similar comedy-horror which sees a man trying to reconnect with nature and his manhood, only to encounter another man, and for death and desolation to result from that encounter.

These films about men and nature hail from similar rugged landscapes where they can't see the forest for the trees, exploring similar themes of how tomes of torment are discussed in deep, long silences that would wake a slumbering bear. They talk about modern masculinity, showing men in trouble and not knowing how to get out of their well of despair.

With Vulcanizadora, Potrykus is asking us to consider the plight of the men who are living examples of detritus and refuse. Men who have no concept of self-care or brotherly support. Men who the concept of a midlife crisis is a farce when their whole adult existence has been a mismanaged crisis. Men who can't be neatly crushed into a box of labels and disorders. And, within that level of disorder and crisis, Potrykus is asking us to find the bleak comedy of the situation, to ensure that we’re laughing with the crow call in the night rather than at it.

When I pushed genre misconceptions aside, Vulcanizadora showed me how to find comedy in the horror of despair, and that is a minor miracle.

Director: Joel Potrykus

Cast: Joshua Burge, Joel Potrykus, Solo Potrykus

Writer: Joel Potrykus

Producers: Hannah Dweck, Matt Grady, Ashley Potrykus, Theodore Scahefer

Cinematographer: Adam J. Minnick

Editor: Joel Potrykus

Screening or Streaming Availability:

*The other being Giles Chan's superb debut feature Jellyfish.

**For a slight taste: Men without dads, and dads without sons. Untethered men floating in the orbit of friends who also don't know who their dad is or where he might be. It's a cyclical relationship of fucked up masculinity. We keep telling these stories because the framework of society is continually broken. 'It's not our responsibility to fix men,' might be the response, but it is. For society to be fixed, men need to be fixed. Or else, they'll just keep confusing a lake for an ocean. At the end of the day, you're still somebody's son.