Right, there’s no beating around the bush: 2024 was a hard year for Australian films.

An engaged film critic should hold their local film industry to account, with the following piece delving into the current state of the Australian film industry and where it might be headed. This is a companion piece to my Best Australian Films of 2024 list, which can be found here.

2024 presented us with a reduction in Aussie film productions after the years of record-breaking peaks that were sustained through the Covid-era partly thanks to various funding initiatives[i]. The Screen Australia drama[ii] report highlights the sobering figure of a near 30 per cent drop off in year-on-year spending for scripted content (their word, not mine), even though the report continues to neglect the active and productive Australian film industry which operates outside of the funding body system.

To put that in raw monetary perspective, in the 2022-23 report, there was some $1.13 billion spent on Australian projects, while in 23-24, $929 million went in Australian projects. I recommend reading Sean Slatter’s less emotive, data-driven examination of the report on IF.com.au for more details.

I mention this to outline that while 2024 was a lesser year for Australian cinema, it is a precursor of what’s to come, and by all accounts, it’s not going to get much better. That is, unless Australian audiences start advocating and fighting for Australian films in cinemas and on streaming services.

But that’s an inherently backwards statement, as the onus isn’t on Australian audiences to seek out Australian films. The industry itself needs to work harder to engage Australian audiences, to encourage chatter about Australian films, and to break through the algorithm of our continued existence to put Australian films in front of faces. Not just the online algorithm we tackle on a daily basis on the modern internet where we’re forced to duck and swerve through computer generated crap in a bid to see what your long lost niece and nephew are up to, but rather the algorithm of reality.

Not to go all ‘old person’ on you all, but when I was a kid, printed film sessions in newspaper made for exciting reading. The possibilities of what was screening at your local multiplex meant that you could plan out a whole day at the cinema and catch three or four films and escape the world for a bit. Newspapers are effectively dead as avenues to get one-stop information, and in turn, that guide for all the cinemas in your city no longer exists. The gradual awareness of filmic information over time has lost its organic reach. Where you might hear about a film and then still catch it in a cinema months later, you’re now having to jump on it immediately for fear it’ll disappear. That means you have to think about going to see a film, and then hope your local cinema is showing it. The ability to stumble upon a film is a rarity, instead you now need to be at this place at this time and have purchased a ticket in advance to show your support otherwise the screening is cancelled.

It's a metric fuck tonne of hurdles for an Aussie film to navigate just to find someone who might want to see it; if only they knew it existed.

Again, the onus isn't on audiences. It isn't even on filmmakers or cinemas. It's on the world as a whole, which is driven in a capitalistic, monocratic manner that actively smothers uniqueness and cultural identity.

Australian films find a way. They persist because creativity persists. They persist because the filmmakers in this country have something to say about the state of this country. They want to hear stories told in our own accent, with the ducks nuts cultural quirks emerging from the way we yarn. This form of art is just one of the ways to communicate with the world and the ideas that continue to burp forward out of its experimental existence.

From a government level, any sense of a mandated national identity on streamers has been scarpered as the notion of quotas for ‘Australian content’ (again, their words, not mine) on platforms has been pushed aside as Anthony Albanese’s Federal government struggles to navigate US free trade deals which act as an impediment to implementing quotas. Any suggestion of this being tackled in a positive manner after the next Federal election and in the second era of a Trump presidency is as fantastical as a giant lizard beating up a giant gorilla. Just less colourful.

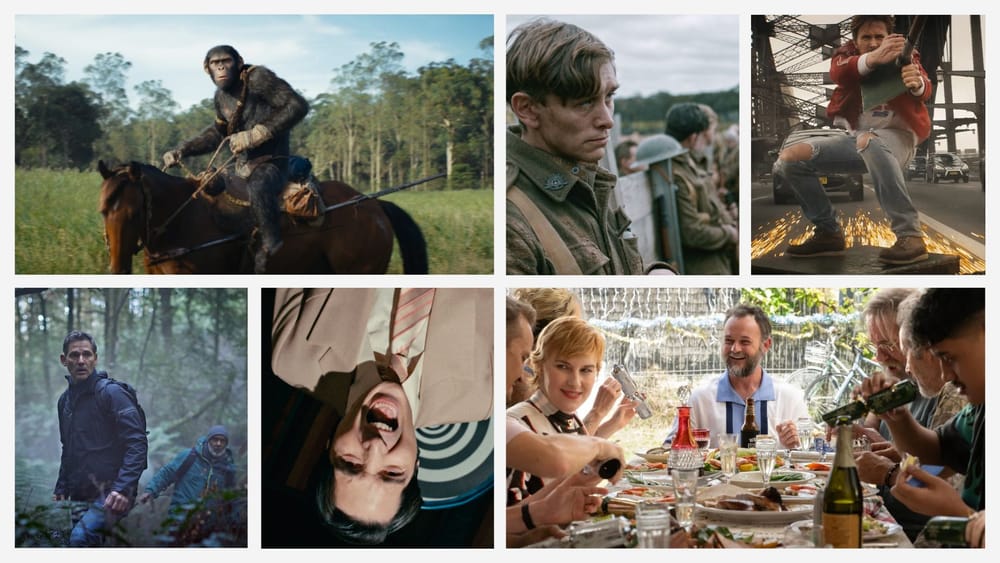

With the funds for the Australian film industry predominantly sitting in the purse of the Australian government (Federal and State alike), Australian stories are once more at risk of fading into the jungle as apes of all sizes wage war on digital playgrounds while not far away, gargantuan killer snakes tackle America’s funny men.

In an act of amelioration, the Federal government is seeking to attract more international productions by cutting back the Location Offset for minimum qualifying Australian production expenditure. I say international, but the reality is that the types of films the government is looking to attract are traditionally American productions which are able to tap into the active post-production facilities and varied landscape Australia has to offer.

Funding bodies should take note that there is a growing industry of cross-continent filmmakers seeking to collaborate ways that aren’t directly from the Anglosphere; see: the Australia India Film Council and the work that Anupam Sharma and his colleagues have been doing to further the amount of Indian-Australian film productions shot across Australia.

The short of it is: expect more global productions to be made in Australia that aren’t always noticeably ‘Australian stories’, even if they were made here.

One last condemnation before I put away the steelcaps, holding myself back from a proper work over of the Australian film industry[iii], of the over 100 plus Australian films released in 2024 many were afraid of engaging in something important, powerful, or in its rarest form, genuinely transformative. Serviceable fare littered Letterboxd with screen bodies rushing to fund yet another run of films from the stalwarts of the Australian film industry, all the while ensuring that minimal space is ceded for new and emerging talent; I’d let my auto predict to fill in their names here, but you’ve already ticked them off in your mind.

A commonality with many of the Australian features and documentaries released in 2024 is the over-representation of men in key roles like writing and directing. The Screen Australia Gender Matters initiative for the 22/23 FY showed a worrying trend of reduced numbers of women in key creative positions, with only producing sitting comfortably over 50% for the three year average. The 23/24 Gender Matters KPI results show a positive trend, but women writers and directors are still continually underrepresented.

Here we are in 2024 with the same men getting continued work as writers and directors while women with established careers abroad on TV and film are funnelled into speed dating events to match up with each other to get a project off the ground.

While the Australian film industry is hardly an outlier compared to the rest of the world, it’s clear that it has a long way to go in ensuring that the voices of women[iv], gender diverse, and non-binary folks are heard in creative roles that guide and drive the narrative of a feature film like writing and directing. Who gets to tell stories on screen is as important as where the stories are told.

The past year has been a rough one, with the trek to find Australian films to hold onto, champion, and shine a spotlight on as examples of cinema that stand up with the greatest out there difficult to achieve on a regular basis.

That is in part why this my Best Australian Films of 2024 list is dominated by shorts and independent fare where the language of cinema features words and phrases that would otherwise be shunned in the routinely culturally and politically stagnant field of Hollywood and screen body funded films. In other words, genuinely memorable experiences that have left an emotional mark[v] on my mind.

I started 2024 with a beleaguered state of mind. I wanted to walk away from this website, from writing about Australian film, from running interviews with filmmakers. I wanted to put it all behind me and never look at it again. I was starting to become a bitter soul, overtly critical and a little bit cruel. But then I spent time talking with people about what some recent Australian films have meant to them and how it’s changed how they see the world.

David Easteal’s The Plains is a shining example of how one film can transform how our relationship with time can be accentuated and amplified to a level where we examine the expenditure of each minute of our day and how to make those seconds worthwhile. I keep thinking of Nicolette Axiak and Jelena Sinik’s two-minute short film, 101 Days of Lockdown, and how these two friends found a form of animation that acted as daily postcards to one another about the simple aspects of their life that mattered each day. Then, I kept thinking about the joyous climax of Tim Carlier’s ecstatic Paco, a film which brings the vitality of Adelaide to life in a manner that still manages to feel positively transformative. In those closing moments, a musical troop marches through the streets of Adelaide towards a sporting ground, their harmony filling the air with joy and lightness. There’s an unbridled enthusiasm for existing and putting out creativity into the world, no matter who might be absorbing it, because sometimes just being creative is enough. Sometimes you don’t need an audience.

I’m critical of the Australian film industry because it means something to me and I want it to continue to exist because of people like David Easteal, Nicolette Axiak, Jelena Sinik, and Tim Carlier. It matters, and somehow, if I keep doing this, then I might matter too.

Finally: Films are not content. Cinema is a church. These artistic endeavours enrich us, build our minds, and grow our worlds. They are not chicken feed to churn through as we move towards inevitable death. They make life worth living, and when we watch them together, communing in the dark, we become stronger, connected in shared experiences. Great filmmaking can birth us into the foyer, blinking at our new world, babes changed by the brilliance of light, sound, and that little thing called empathy.

With that all said, won’t you go read the Best Australian Films of 2024 for me?

[i] https://theconversation.com/400-million-in-government-funding-for-hollywood-but-only-scraps-for-australian-film-142979#:~:text=On%20July%2017%2C%20Prime%20Minister,success%20in%20managing%20COVID%2D19.

[ii] Once again, Screen Australia opts for the term ‘drama’ to reflect all non-documentary forms of filmmaking, as if drama is the only genre that matters.

[iii] Take How to Make Gravy for example, a film which works to the recipe and forgets to push the boundaries of its existence by adding that dollop of tomato sauce, you know, for the sweetness and extra tang. While I’m loathe to put forward a ‘worst of’ list – after all, omission from conversation can be as damning as being part of the conversation itself –, I do find the particular strand of manufactured Australiana within How to Make Gravy unpalatable, with the film standing as an example of why many have turned away from Australian films altogether.

[iv] Transwomen are women.

[v] A reminder that joy, fear, disgust, and sorrow are each emotions. Emotional films don’t always have to leave you in tears of sadness. They can leave you with tears of joy too.