90s All Over Me takes inspiration from 80s All Over, the Drew McWeeny/Scott Weinberg podcast that attempted to review every major film release of the 80s one month at a time; that podcast ended circa early 1985 and McWeeny has continued the project on his Substack. The aims of this series are somewhat more modest; rather than covering every month and release in said month, each entry will cover a year of the 1990s, focusing solely on what I’ve seen from that year. The first half of each instalment spotlights what I saw theatrically at the time, contextualising those works in my own moviegoing journey from ages seven to 17 as well as their wider cultural import. The second half covers every other release I’ve seen of that year across physical media, television, and streaming.

Read the previous instalments on 1989, 1990, 1991, and 1992.

- 1993 Total films seen: 118

- Total seen theatrically: 10

- VHS/TV/DVD/Streaming: 108

Theatrical

As an 11-year-old who read Archie comics and not industry tea leaves, I enjoyed all of these cinema experiences, but looking at this list—four sequels, seven films drawn from other intellectual property—it’s evident which direction the Hollywood tide was turning in 1993. I was also starting to hanker for films that were more geared towards adults—piqued by working through the James Bond, Bruce Lee, and Stallone back catalogues on VHS—and testing the waters for maturer fare, some of which I’ll spotlight below. But first …

Jurassic Park

Director: Steven Spielberg; Cast: Sam Neill, Laura Dern, Jeff Goldblum, Richard Attenborough; Writer: David Koepp.

Thrilling at age eleven, and still holds up incredibly well. Where every sequel has progressively escalated the dinosaur mayhem, here Spielberg—drawing from his own proven playbook for Duel and Jaws—is conservative, milking their onscreen moments for maximum impact. The suspenseful blocking and strategic humour of the T-Rex scene is a true filmmaking masterclass. While the 1990s yielded lots of sequels to 80s successes, as well as birthing franchises whose entire cradle-to-grave lifespan fell between 1990 to 1999, it produced surprisingly few franchises—especially compared to 1980s and 21st century properties—that were wholly born of the decade and still thrive today: Jurassic Park was the first, with just a handful more (Bad Boys, Mission: Impossible, The Matrix) to follow.

Super Mario Bros: The Movie

Directors: Annabel Jankel, Rocky Morton; Cast: Bob Hoskins, John Leguizamo, Samantha Mathis, Dennis Hopper; Writers: Parker Bennett, Terry Runte, Ed Solomon.

The live-action adaptation of the Nintendo game series was briefly—at least in my playground—as major an event as Jurassic Park. Then we saw the movie. Lots of good people toiled on this garish but perhaps undeservedly infamous film, among them Bob Hoskins, Dennis Hopper, Bill & Ted writer Ed Solomon, Oscar-winning DP Dean Semler, The Killing Fields director Roland Joffe (as producer), frequent James Cameron editor Mark Goldblatt, and Back to the Future composer Alan Silvestri. Entertaining on a scene-to-scene basis, but neither fish nor fowl, the movie’s failure benched this particular IP as fodder for cinema for three decades.

The Three Musketeers

Director: Stephen Herek; Cast: Chris O’Donnell, Kiefer Sutherland, Charlie Sheen, Oliver Platt, Rebecca De Mornay; Writer: David Loughery.

Perhaps the most “1993” of all these titles, The Three Musketeers follows the template of Young Guns and Mobsters (hot young things play old timey archetypes), stars Kiefer Sutherland and Charlie Sheen, features Tim Curry and Michael Wincott as villains (see also Home Alone 2 and Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves), has Robin Hood’s Bryan Adams crooning on the soundtrack alongside Sting and Rod Stewart, and is helmed by Stephen Herek of Bill & Ted and Don’t Tell Mom the Babysitter’s Dead. This is an enjoyable retread of the oft-filmed Musketeer lore that holds up respectably, if not spectacularly, with well-staged action scenes cleanly shot by the aforementioned (and busy) Dean Semler. Casting Charlie Sheen as the devout Aramis remains a winking choice 30+ years later.

Beethoven’s 2nd and Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit

Beethoven and Sister Act were both 1992 releases, making this a rapid turnaround for both sequels ala Look Who’s Talking Too. I remember very little of Beethoven’s 2nd, apart from Chris Penn falling from ahigh and landing headfirst in a tree trunk, which in 1993 felt the height of comedy. I’m sure it’s fine. Sister Act 2, which took an existing script and tweaked it to Whoopi’s persona, is a predictable but amiable programmer.

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles III

Unlike the two sequels above, this came out two years after the previous instalment, though I don’t believe that time was spent refining the material. It certainly wasn’t spent refining the turtle suits, now even more plastic and fake than The Secret of the Ooze. Perhaps two years was too long, as the Turtle mania had largely subsided: I remember seeing this on opening weekend in a largely unoccupied theatre. Having said that, I enjoyed the film then and it remains very watchable.

Addams Family Values

Widely adored and hallowed as that rare follow-up that improves upon its predecessor. I appreciate its wit and cinematic flair, but it doesn’t feel substantially different to the Home Alone 2 or Lethal Weapon 2 formula of “same, but different, and more”.

The Beverly Hillbillies

Penelope Spheeris’ follow-up to Wayne’s World, updating the 1960s sitcom. At eleven I thought this was hilarious; at 42, I’ll meet it halfway at amusing.

Dennis the Menace

I don’t envy child actors and am generally sympathetic to even the most affected of child performances, but this kid is rough. Nonetheless, tolerable post-Home Alone John Hughes-scripted slap-schtick.

Mrs Doubtfire

The best of the comedies I saw in theatres in 1993, with a sturdy if saccharine emotional core and a tour de force performance from Robin Williams.

The Rest: From The Fugitive to Yahoo Serious

I mentioned hankering for more adult fare in 1993. Chief in that echelon was The Fugitive, an immediate rental when it hit home video. The Fugitive draws from television source material like Addams Family Values, The Beverly Hillbillies, and Dennis the Menace, but the film transcends its source series and medium. Headlined by an oft-silent Harrison Ford and conversely motor-mouthed Tommy Lee Jones as hunted and hunter respectively, the film is meaty, propulsive, skilfully directed by Under Siege’s Andrew Davis, and a rare action thriller to be Oscar-sanctioned (see more on this topic below). On my last rewatch, I was reminded of Richard Donner’s emphasis on verisimilitude when making Superman: The Movie; though The Fugitive doesn’t have quite as outlandish a concept to land, it nonetheless tackles its IP popcorn premise seriously and credibly.

Rising Sun was another adult thriller I was keen to see, enticed by reading Michael Crichton’s source novel—after seeing and reading Jurassic Park—and Sean Connery’s casting. This proved to be one of the very first times, if not the first, that I read a book and was disappointed by the adaptation. In retrospect, Rising Sun is, like its source, a serviceable potboiler with some Orientalist sheen.

Another novel I read and hankered to see on film was The Firm. I love Sydney Pollack’s smart and polished adaptation of the John Grisham novel, with its stacked cast, effective streamlining of the material, and use of its Memphis setting. It’s also, like 1990’s Pretty Woman and another title spotlighted later in this piece, one of those fascinating post-Reaganomics 90s titles where money—abundance of it or lack thereof—is the fetishistic catalyst for much of the drama. Another Grisham adaptation of 1993, The Pelican Brief, was sturdily executed by the dependable Alan Pakula (his penultimate project).

I filed my last piece prior to Gene Hackman’s passing, hence I’ll take a moment here to sing the praises of this titan who, following his Oscar-winning supporting turn in 1992’s Unforgiven, became an ever-welcome part of the tapestry of the 1990s: essaying roles big and small, never bad, always good—even in bad titles—and often great. Hackman never doodled—or showcased doodle—in art films like Harvey Keitel (see below), never suffered for his art like Pacino or Hoffman, never transformed for a role like De Niro; he was very much a company guy working on comfortable productions, but always a consummate pro drawing from that bountiful reservoir of gravitas time and again. In The Firm, he’s the crooked mentor and agreeable serpent; in Geronimo, he’s the military man of influence. Both were types he’d played before and would play again in the 90s, sometimes mixing and matching, but always bringing shading and conviction. In The Firm in particular, his ostensibly amiable snake oil salesman character enjoys an emotional arc all his own, inessential to the main story but delivered with nuance and thoughtfulness. And when Hackman occasionally digressed from his stock of types, such as playing a low-rent, low-status B-producer in Get Shorty, results were especially delightful.

Point of no Return—titled The Assassin in Australia and a remake of Nikita—was another film I hankered to see, enticed by the striking poster design of Bridget Fonda in a sleek dinner dress holding a silencer. Though directed capably by John Badham and featuring a charmingly ambiguous turn by Gabriel Byrne as the Henry Higgins remoulding Fonda’s Eliza Doolittle, this is really Fonda’s show. I love and miss Bridget Fonda—she’s been retired since 2002—but her filmography is largely devoid of classics, so opportunity and motivation to revisit her work are relatively thin.

Two more titles I hankered to see, both featuring stars—Clint Eastwood and Sylvester Stallone—who would become fast favourites, were the classy, suspenseful In the Line of Fire and bombastic, stunt-laden Cliffhanger. Both films are impressively executed by their imported European directors, Wolfgang Petersen and Renny Harlin. Both filmmakers had big American productions already under their belt, but here were working with major stars renowned for dominating their productions. As the teaser below highlights, the entire selling point of In the Line of Fire boiled down to “Eastwood protects President”.

However, as the finished products attest, both skilfully navigated this terrain. In the Line of Fire is easily Petersen’s best English-language film, and Cliffhanger probably Harlin’s. Both films are enlivened by playful villain performances from Johns Malkovich and Lithgow respectively, the former Oscar-nominated for his efforts. Between The Fugitive, Cliffhanger, In the Line of Fire, Jurassic Park, and The Firm, 1993 was an excellent year for well-above-average mainstream thrillers.

Where Stallone bounced back with Cliffhanger following two unsuccessful comedies, action rival Arnold Schwarzenegger stumbled with Last Action Hero. Another misstep for John McTiernan after Medicine Man, Last Action Hero was a perfect storm of troubled production and preposterously over-hyped release, with the film at the centre of all the fuss a messy family-action-comedy that’s infrequently funny, too rough for the family, and not rough enough for action fans. A director with a flair for the postmodern and the intertextual—a Joe Dante or a Robert Zemeckis or a John Landis—might have nailed the tone, but McTiernan falters. Yet another film shot by Dean Semler, who between Super Mario Bros, Last Action Hero, and 1995’s Waterworld enjoyed (perhaps) a front row seat on three of the most notorious productions of the 90s. The Hamlet parody clicks though.

Steven Seagal also faltered with his directorial debut and swansong, On Deadly Ground. The film is competently made and its environmental message would be more warmly received today, but viewers couldn’t quite take Steven Seagal delivering said message seriously, nor the Dances with Wolves-style transformation he undergoes in Act 2.

Charting a course decidedly down the middle were Bruce Willis with Striking Distance—essaying a less charismatic version of his burnout sleuth from The Last Boy Scout—along with Wesley Snipes in Boiling Point, Dolph Lundgren in Joshua Tree, and Van Damme in Nowhere to Run. Van Damme also headlined John Woo’s flamboyant and very engaging American debut Hard Target. Sniper launched a franchise that’s now 11 films strong, while the defanged Robocop 3 was so poor it makes Robocop 2 look like Robocop.

Rob Cohen helmed a very “Hollywood” biopic of Bruce Lee in Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story, while over in Hong Kong Lee’s martial arts movie offspring Jackie Chan and Donnie Yen headlined Crime Story—a police procedural slim on martial arts set pieces—and Iron Monkey respectively, the latter a prequel of sorts to Once Upon a Time in China.

The action genre was flanked in 1993 by two parodies. The hilarious Hot Shots: Part Deux took aim specifically at the Rambo series, but other action and high-profile films fell prey to its parodic sights, including Terminator 2 and Apocalypse Now. Less funny, but perhaps more tasteful, was Mel Brooks’ Robin Hood: Men in Tights, parodying Costner’s Robin Hood. The erotic thrillers of the era were also parodied by Carl Reiner in Fatal Instinct, the least of these three but with a game, energetic cast including Armand Assante, Sherilyn Fenn, and Sean Young.

Like action movies, erotic thrillers continued to survive—if not thrive—in 1993 despite being parodic targets, with several releases chasing the tail of Basic Instinct: Body of Evidence with Madonna and Willem Dafoe, Dream Lover with James Spader and Madchen Amick, and Sliver, directed by Phillip Noyce from an Ira Levin novel and reuniting Sharon Stone, less successfully, with the genre and screenwriter (Joe Esterhaz) of her previous triumph.

Satellites of the genre included polished studio thrillers Blink and Malice, spirited indies Red Rock West and Romeo is Bleeding—Peter Medak’s bonkers noir affording Gary Oldman a rare post-Dracula lead in a period mostly essaying colourful supporting antagonists—and conversation pieces Boxing Helena and Indecent Proposal. Few had nice things to say about Jennifer Lynch’s debut, underwhelming dramatically and accused of misogyny, but Indecent Proposal was a big hit. The other Reaganomics mutant offspring of 1993, Adrian Lyne’s film handles its premise—millionaire Robert Redford offers broke married couple Demi Moore and Woody Harrelson a million dollars to sleep with Moore—with lots of sizzle but little steak and an overall evasive touch; Redford’s casting and suave performance help the film circumvent, like Pretty Woman, the murkier implications of its story.

A couple of friends have complained I talk too much about the Oscars and box office in these pieces. I disagree: while neither is a seal of quality or longevity, when I touch on these things I do so because, as part of the context and circus of the film industry, awards and box office dictate what achieves some measure of posterity from a given year and what gets made in subsequent years. A case in point: despite Batman Returns’ wobbly reception, the long tail of Batman’s success was still evident in 1993 with animated film Batman: The Mask of Phantasm and, especially, Henry Selick’s stop-motion-animated musical Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas.

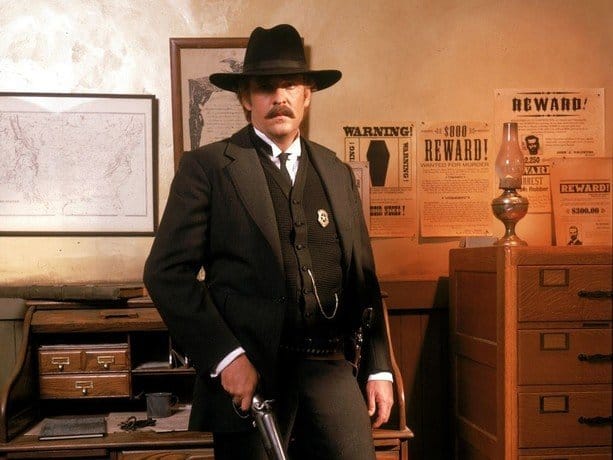

Meanwhile, the dustier tail of Dances with Wolves and Unforgiven is evident in A Perfect World, an effective Eastwood-directed road movie thriller with the director himself chasing down Kevin Costner’s escaped convict with child in tow; Lawrence Kasdan’s luxuriously paced Costner-starring character study Wyatt Earp, epic and thoughtful but also bloated and not always engaging; the smaller, swifter, less thoughtful, but far more entertaining Tombstone; Mario van Peebles’ solid black Western Posse; and Walter Hill’s abovementioned Geronimo.

None of these children of Dances with Wolves or Unforgiven were courted by the Academy, but 1993 is a rare year where I like all the Best Picture nominees unconditionally. Competing alongside The Fugitive were victor Schindler’s List, The Piano, The Remains of the Day, and In the Name of the Father.

The Piano remains Jane Campion’s richest, most accomplished, most coherent film. Unlike Indecent Proposal, it wrestles with the thorniness of its concept—in mid-1800s New Zealand, a mute woman is coerced into sexual favours in exchange for her piano, one key at a time—perhaps because the seducer is Harvey Keitel and not Robert Redford. Keitel, Holly Hunter, and Anna Paquin (both actresses Oscar-minted) are superb, but the best performance is Sam Neill, who’d been quietly adding feathers to an already impressive filmography since the start of the 90s—some good like Hunt for Red October, some not so good like Memoirs of an Invisible Man, though his work there is reliable—before pulling off 1993’s one-two punch of Jurassic Park and The Piano.

Emma Thompson has the distinction of featuring in two 1993 Best Picture nominees, along with Kenneth Branagh’s delightful, sun-kissed ensemble comedy and return to Shakespeare Much Ado About Nothing. In the Name of the Father is a strong political prison drama from Jim Sheridan, with a compelling lead performance by Daniel Day-Lewis, but I prefer The Remains of the Day, arguably the best work produced by the Merchant Ivory producer-director team: I love the film’s stillness and composure, its measured pacing, the unspoken yearnings of leads Anthony Hopkins and Thompson, and its portrait of the deeply entrenched, stifling hold of the British class caste.

Mining similar territory of class and unspoken yearnings to The Remains of the Day—and echoing the triangular romantic dynamics of The Piano and Indecent Proposal—was Martin Scorsese’s formally ravishing period drama The Age of Innocence. The film afforded yet another 1993 one-two punch—to the abovementioned Daniel Day-Lewis—along with meaty, nuanced roles to Michelle Pfeiffer and Winona Ryder.

However, the undisputed one-two punch of 1993 belonged to Steven Spielberg with Jurassic Park and Schindler’s List. The latter is masterful filmmaking, impeccably crafted and performed, intelligent and harrowing but—like Jurassic Park—strategically finding moments of levity for emotional release. If awards and box office dictate what achieves some measure of posterity and what gets made in subsequent years, the perhaps very obvious and long-entrenched message of 1993 was to let Steven Spielberg make movies, which he would do from within his very own studio in the second half of the 90s.

Braveheart and its Oscar victory were two years away, but for his 1993 directorial debut Mel Gibson chose more modest material in The Man Without a Face. A contemporary-set, not-remotely-violent drama about friendship between a fatherless boy and disfigured man, the film is an outlier in Gibson’s directorial filmography, though the themes of martyrdom and persecution that pervade his full-bodied historical epics and many of his performances are apparent.

Another Bildungsroman was Searching for Bobby Fischer, scripted and directed by Schindler’s List screenwriter Steve Zaillian: a film I admire but can’t say I particularly warm to, despite its evident craft and gifted cast. Robert De Niro also made his filmmaking debut with A Bronx Tale, like Gibson choosing modest coming-of-age material and steering young co-stars. He also appeared in This Boy’s Life in one of his most grating performances, channelling his worst acting excesses and tics into his scum-bum role as Leonardo Di Caprio’s abusive stepfather.

A crop of young stars both new and rising—some of whom went the distance, others crashing and burning in Hollywood’s survival of the fittest—made their presence felt in 1993, among them DiCaprio in This Boy’s Life, DiCaprio and Johnny Depp in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, Depp in Arizona Dream, and the young cast of Richard Linklater’s very watchable Dazed and Confused.

Like Beethoven’s 2nd and Sister Act 2, Wayne’s Word 2 unspooled a mere year after the original, and while there are good gags, it shows. Myers also headlined the enjoyable So I Married an Axe Murderer, while Coneheads saw Dan Aykroyd and Jane Curtin reprising their Saturday Night Live roles as pointy-headed extra-terrestrials. Directed by Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles’ Steve Barron and co-scripted by Aykroyd—with three other scribes keeping in check the Aykroydian excesses of Nothing but Trouble—Coneheads is amusing at best but I have a big soft spot for it.

A big part of comedy is comfort food, so Aykroyd films of this era hit that spot; ditto seeing Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau in sparring form in Grumpy Old Men. Similarly, in seemingly every piece in this series I’ve said nice things about Kevin Kline, so my fondness for political comedy Dave should be unsurprising. Other comedies of 1993 included Cool Runnings, Made in America, Heart and Soul, and Harold Ramis’ dexterous blend of black comedy, rom-com, and Capra-corn Groundhog Day, showcasing some of Bill Murray’s finest and most textured screen work. Murray also appears as a gangster in a little gem called Mad Dog and Glory alongside Robert De Niro and Uma Thurman, under the unlikely direction of Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer’s John McNaughton.

While Bill Murray stretched incrementally with Groundhog Day and Mad Dog and Glory, Woody Allen remained firmly in his wheelhouse with Manhattan Murder Mystery. Dismissed by the filmmaker as a light trifle—and a timely one following his offscreen scandals—the film makes the curious stylistic choice of employing the handheld Cassevetes-esque shooting style of Allen’s previous film Husbands and Wives, which doesn’t always gel with the old-school Allen comedy. But the film entertains and there’s pleasure in seeing Allen and Keaton onscreen again for the first time since Manhattan.

Other veteran directors with major releases in 1993 included Robert Altman with Short Cuts, a multi-character network drama adapted from Raymond Carver’s short stories; the first of Polish director Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Three Colours trilogy, Three Colours: Blue; Oliver Stone’s third Vietnam drama Heaven & Earth, wrestling with the conflict from the vantage point of Le Ly Hayslip, a Vietnamese woman whose life was upended by the war; and Brian De Palma in crowd-pleasing mode in the satisfying and oddly touching gangster thriller Carlito’s Way.

Rom-coms and communal tearjerkers continued to be commercially and critically viable, most clearly demonstrated by the success of rom-com Sleepless in Seattle, the second of three teamings of Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan, cleverly building a romance between characters who don’t meet until film’s end.

Notable tear-jerkers of the year included Shadowlands, a gentle portrait of author C.S. Lewis—tenderly played by Anthony Hopkins—and his relationship with poet Joy Davidman, with Debra Winger dying of cancer on screen for the second time in her career; My Life, directed by Ghost screenwriter Bruce Joel Rubin, in which a dying Michael Keaton records videos for his unborn child; and period romance Sommersby, remaking the French film The Return of Martin Guerre with Richard Gere subbing for Gerard Depardieu as a soldier returned from war who may not be who he says he is, with Jodie Foster as his ambivalent wife.

Sandwiched between Quentin Tarantino’s debut Reservoir Dogs and sophomore triumph Pulp Fiction were True Romance and Killing Zoe. The former, scripted by Tarantino and directed by Tony Scott, is my favourite thing either filmmaker has ever created: funny, fresh, coarse and violent but big-hearted, served with Scott’s signature style and polish, and peppered with excellent performances from leads Christian Slater and Patricia Arquette to colourful support from Gary Oldman, Dennis Hopper and Christopher Walken in an all-timer scene, Bronson Pinchot, Chris Penn and Tom Sizemore, James Gandolfini, Brad Pitt, Val Kilmer, and more. There’s also a wonderful Hans Zimmer score riffing on Carl Orff’s ‘Gassenhauer’ (memorably used in Malick’s Badlands).

Meanwhile, Killing Zoe marked the directorial debut of Roger Avary, Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction co-screenwriter, former Video Archives co-worker, and current Video Archives podcast co-host. Killing Zoe belongs in the camp of Tarantino’s imitators, but has more crude charm than typical. That film’s lead, indie king Eric Stoltz, also pops up in one of those “you had to be there” 90s indies with an upmarket cast, Bodies, Rest and Motion.

Gay characters and relationships were becoming more visible on screen in 90s releases, often through independent or foreign titles and often adapted from other sources. That’s very much the case with Denys Arcand’s Canadian stage adaptation Love and Human Remains; fellow Canuck David Cronenberg’s stage adaptation M. Butterfly, featuring Jeremy Irons reuniting with his Dead Ringers director; Fred Schepisi’s witty and nimble stage adaptation Six Degrees of Separation, headlined by Stockard Channing, Donald Sutherland, and Will Smith in an important early role departing from his Fresh Prince persona; Ang Lee’s The Wedding Banquet; and Cuban drama Strawberry and Chocolate. Jonathan Demme’s Philadelphia—starring Tom Hanks in his first Oscar-winning role as a wrongly-dismissed lawyer dying of AIDS and Denzel Washington as the homophobic lawyer representing him—was an empathetic work spurred into existence by the criticisms levelled at Demme for transphobic elements of The Silence of the Lambs.

In previous pieces I mentioned films watched on TVs wheeled into classrooms for educational or edification purposes. A couple of 1993 titles in that canon were underdog sports drama Rudy and true-life survival drama Alive, about plane crash survivors in inhospitable surrounds forced into cannibalism. Not wheeled into the classroom: Trey Parker’s Cannibal: The Musical.

Horror releases of 1993 included remake Body Snatchers, one of two Abel Ferrara films in theatres alongside Dangerous Game; sequels Jason Goes to Hell and Godzilla vs Mecha-Godzilla; anthology Body Bags hosted by John Carpenter; Joe Dante’s William Castle homage Matinee; Dario Argento’s Trauma; and Leprechaun. At the more mainstream end of the genre, a bespectacled and flat-topped Michael Douglas headlined Joel Schumacher’s sweaty Falling Down and a bearded, gnarly Brad Pitt headlined Kalifornia. Like John Grisham, Stephen King was adapted twice in 1993, with Needful Things and The Dark Half, the latter George A. Romero’s final film of the 90s.

Australian releases of 1993 included Blackfellas, James Ricketson’s drama about struggles facing contemporary Indigenous men; Rolf De Heer’s sometimes repellent, never boring Bad Boy Bubby; a pedestrian potboiler in Gross Misconduct; both The Heartbreak Kid and The Nostradamus Kid, both good; family film The Silver Brumby; and Reckless Kelly, one of three truly singular oddball works—along with Young Einstein and Mr. Accident—from the hugely resourceful and sadly M.I.A. director-writer-producer-star-composer Yahoo Serious.

From Australian directors toiling abroad came the aforementioned Sliver and Six Degrees of Separation, but also The Real McCoy, another anonymous and unmemorable work from Russell Mulcahy following Blue Ice; family hit Free Willy from capable journeyman Simon Wincer; and Peter Weir’s Fearless, a sharp and earnest film grappling with the confusing after-effects of trauma and featuring another tremendous, exposed nerve performance from Jeff Bridges following The Fisher King.

Finally, there’s no elegant segue or cohesive theme to introduce or unite these final films, except to say here are some foreign films: from Japan, Takashi Kitano’s melancholic Sonatine and notable anime Ninja Scroll; from the UK, Peter Greenaway’s taxing The Baby of Mâcon and Mike Leigh’s Naked, featuring a tour de force talent-announcing performance from David Thewlis; and from Spain, the Almodovar comedy Kika.

For the record, some notable films of 1993 that I have not included because I haven’t seen them: The Good Son, What’s Love Got to Do With It, Gettysburg, The Joy Luck Club, We’re Back: A Dinosaur’s Story, Poetic Justice, Menace II Society, Benny & Joon, Flesh and Bone, Wrestling Ernest Hemingway, Hocus Pocus, Even Cowgirls Get the Blues, Son in Law, Another Stakeout, The Thing Called Love, Cop and a Half, Look Who’s Talking Now, The House of the Spirits, The War, and Farewell my Concubine.

If you’re still here, thanks for enduring and see you back here for 1994, when Jim Carrey explodes, Macauley Culkin implodes, Forrest Gumps, Tarantino gimps, and Tim Robbins crawled through a river of shit (not AntiTrust) and came out the other side. Til then …