90s All Over Me takes inspiration from 80s All Over, the Drew McWeeny/Scott Weinberg podcast that attempted to review every major film release of the 80s one month at a time; that podcast ended circa early 1985 and McWeeny has continued the project on his Substack. The aims of this series are somewhat more modest; rather than covering every month and release in said month, each entry will cover a year of the 1990s, focusing solely on what I’ve seen from that year. The first half of each instalment spotlights what I saw theatrically at the time, contextualising those works in my own moviegoing journey from ages seven to 17 as well as their wider cultural import. The second half covers every other release I’ve seen of that year across physical media, television, and streaming.

Read the previous instalments on 1989, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, and 1995.

- 1996 Total films seen: 150

- Total seen theatrically: 27

- VHS/TV/DVD/Streaming: 123

Theatrical

Independence Day

Director: Roland Emmerich; Cast: Will Smith, Bill Pullman, Jeff Goldblum, Randy Quaid; Writers: Roland Emmerich, Dean Devlin.

Roland Emmerich and Dean Devlin’s signature collaboration—though there are better ones—Independence Day was omnipresent in 1996. An Irwin Allen-style take on alien invasion, fourteen-year-old me found it very enjoyable in 1996, if not completely satisfying, the hype machine having built up expectations it couldn’t possibly meet. Like Batman Forever, it’s been a rollercoaster from liking to loathing to liking to begrudging respect, with its terrible 2015 sequel serving to accentuate its merits. There’s plenty of killer, but also a lot of filler.

Mars Attacks!

Director: Tim Burton; Cast: Jack Nicholson, Glenn Close, Pierce Brosnan, Michael J. Fox, Sarah Jessica Parker, Annette Bening, Tom Jones, Danny De Vito, Rod Steiger; Writer: Jonathan Gems.

Though not an Independence Day parody, Mars Attacks! nonetheless feels like its mischievous, parasitic, snickering rebel sibling, which makes it both obnoxious and endearing. Tim Burton’s colourful sci-fi comedy, studded with stars gladly hamming it up in the spirit of the assignment, is terrific and one of the director’s last unconditionally fun films.

Twister

Director: Jan De Bont; Cast: Bill Paxton, Helen Hunt, Jami Gertz, Cary Elwes; Writers: Michael Crichton, Anne-Marie Martin.

A more grounded, scrappier take on the disaster film than Independence Day—one that ushered in a wave of natural disaster movies over the rest of the decade and its own belated 21st century sequel—Twister is also Jan De Bont’s last unconditionally fun film. Looking back, it’s amusing that European directors delivered the biggest popcorn Americana hits of 1996, this one deep in the Heartland.

Mission: Impossible

Director: Brian De Palma; Cast: Tom Cruise, Emmanuelle Beart, Jean Reno, Ving Rhames, Jon Voight; Writers: David Koepp, Steve Zaillan, Robert Towne.

Great fun. Loved it then, love it now, and while I’ve enjoyed the direction the franchise has gone this remains my favourite, in part because of its tightness and economy. Back in 1996 the media grumbled how Hollywood action movies were just special effects soups, but looking at these films it’s striking—compared to modern spectacle films—how sparse and strategic the spectacle scenes were: five twisters in Twister; one multi-city sequence of devastation and two sequences of aerial dogfights in Independence Day, and here an exploding fish tank (more exciting than it sounds), the fight atop the bullet train, and the suspenseful CIA vault break-in. Between and around those excellent sequences, Mission Impossible’s a Tom Cruise star vehicle brushing against a Brian De Palma espionage thriller, and it’s a fascinating fusion from the era when Cruise sought to work with the very best of filmmakers, as opposed to the three or four guys in his inner circle (who are nonetheless gifted).

Jerry Maguire

Director: Cameron Crowe; Cast: Tom Cruise, Renee Zellwegger, Cuba Gooding Jr., Jonathan Lipnicki; Writer: Cameron Crowe.

Not really my thing, but very good at what it does, and with Mission: Impossible makes for a hell of a one-two movie star punch for Cruise.

In Love and War and The Chamber

Not quite the one-two movie star punch intended for Chris O’ Donnell, clearly being groomed for stardom after Batman Forever, which he would find on TV in the 21st century. On paper, these are strong choices: starring as Ernest Hemingway in a wartime romance alongside Sandra Bullock, helmed by the distinguished Richard Attenborough; and headlining a John Grisham adaptation with stacked support from Gene Hackman and Faye Dunaway, in a genre (legal thriller) that was pretty durable movie comfort food throughout the decade, from A Few Good Men to the Grishams to another title this year, Primal Fear. But both The Chamber and In Love and War are terminal snoozes.

Eraser

Classic Arnold, though not an Arnold classic. A comfort food assemblage of Arnold action beats and wisecracks that never quite gets the pulse racing, this was nonetheless executed with some junky flair by The Mask’s Chuck Russell and was clearly Schwarzenegger’s penance for Junior.

Daylight

The second of three 1996 actioners from the three titans of 90s action movies & famed co-restauranteurs. However, Daylight has more in common with Twister and Independence Day: it’s an Irwin Allen-style architectural disaster movie with Stallone—continuing to very incrementally play against type following Assassins—leading an ensemble of whining character actors trapped in a collapsed tunnel to safety. My Stallonean biases are well-documented, both here and throughout this series, so naturally I like this one a lot, plus it continues Stallone’s stellar run of 90s character names: Snaps Provalone, Gabe Walker, John Spartan, Ray Quick, Joseph Dredd, Robert Rath, and now Kit Latura.

Last Man Standing

Walter Hill’s dusty, underrated Prohibition-era riff on Yojimbo and A Fistful of Dollars, with Bruce Willis’s vagabond playing rival Italian and Irish gangs against one another. Directed with style by Hill and effectively scored by Ry Cooder, this sees Willis neither reverting to type like Arnold in Eraser nor incrementally stretching like Stallone in Daylight: it’s a straight-down-the-middle Bruce performance, but neither this nor 12 Monkeys nor the following year’s The Fifth Element were no-brainer safe commercial choices in the wake of Die Hard With a Vengeance, and revisiting his eclectic 90s filmography it’s evident Willis was frequently following his own muse, with interesting results.

Ransom

This film and Eraser I have an abiding fondness for as the first MA-rated films I saw theatrically, the kind of thing only deeply nerdy film fans remember and care about (ditto American Psycho, Boys Don’t Cry, and Chopper as my first R-rated theatrical screenings in 2000). As a huge Mel Gibson fan I was super-psyched for Ransom, the gripping trailer above with its emphatic punctuation point of “Give me back my son!!” further stoking that excitement. It didn’t disappoint, and Ron Howard’s then-atypical film holds up remarkably well as a first-class, satisfying mainstream thriller for adults.

Chain Reaction

I was also stoked for Chain Reaction as a huge fan of The Fugitive and a fan of Keanu, though the previous year’s Johnny Mnemonic had planted the seed that perhaps he wasn’t very good at his job. The finished product didn’t really help that cause and was a disappointment from director Andrew Davis. I’m sure it’s fine as far as movies where hunky scientists outrun hydrogen bomb explosions on their motorcycles.

Michael Collins

These next two films were notable viewings as I saw them with both parents, an atypical experience as dad didn’t go to the movies very often. However, I remember both fondly for reasons that have nothing to do with nostalgia. Neil Jordan’s follow-up to The Crying Game and Interview with the Vampire, this biopic of the titular Irish freedom fighter inevitably brushes against some of the cliches of the genre, and Julia Roberts is an unnecessary bit of Hollywood ornamentation, but for the most part this is a sturdy, meaty film with more vinegar and grit than the norm and an excellent lead performance from Liam Neeson.

The Ghost and the Darkness

Easily Stephen Hopkins’ best film, a well-crafted, period-set “Jaws in Kenya” with two deadly lions. This was Val Kilmer’s first major post-Batman Forever role; the prickly star did not get along with producer/miscast co-star Michael Douglas, as memorably recounted by screenwriter William Goldman, and the lack of chemistry is obvious onscreen. Bad blood between actors didn’t sink Jaws, but Jaws wasn’t directed by Stephen Hopkins.

101 Dalmatians

Once again, to all those who hold up John Hughes as a Salinger-esque voice of a generation and recluse, J.D. Salinger didn’t make bank writing movies where Richard Widmark got hit on the head with a coconut before falling into sewerage and getting bitten in the nuts by a piranha. Slap-schtick aside, this OG live-action Disney remake at least has cute dogs and Glenn Close vamping it up.

Jack and The Nutty Professor and The Cable Guy

Three comedy giants—Robin Williams, Eddie Murphy, Jim Carrey—at very different career junctures and crossroads. Jack gets a bad rap, perhaps because director Francis Coppola’s presence raises expectations, but the film is exactly what’s on the packaging: an amusing but schmaltzy Robin Williams family film, with Williams in total control of his instrument. So too are Eddie Murphy, entering family-friendly fray for the first time with The Nutty Professor—albeit with one foot in edgier terrain as Buddy Love, the antagonistic Id to lovable lard Sherman Klump—and Jim Carrey, on the cusp of embracing more sentimental material but an absolute comedic beast in Ben Stiller’s The Cable Guy as a stalker raining chaos upon Matthew Broderick’s parade.

Space Jam and Muppet Treasure Island

Neither deserving of a generation’s affections nor worthy of outright dismissal as a crass exercise in corporate synergy, Space Jam is a perfectly fine programmer that pales in class, craft, and comedy to Who Framed Roger Rabbit and the bulk of the preceding Looney Tunes canon. Muppet Treasure Island makes better use of its felt stars, aided by the sturdy frame of Robert Louis Stevenson’s oft-told tale and a healthy non-Miss Piggy injection of ham from Tim Curry, but Jim Henson’s creations too have had more memorable exploits. As a thought experiment, consider if the Muppets co-starred in Space Jam and Looney Tunes did Treasure Island. The switch makes sense, given the Muppets’ previous interactions with IRL celebrities and Looney Tunes’ adaptations of Robin Hood, opera, and Casablanca.

Star Trek: First Contact

Indisputably the best of the Next Generation crew’s feature film adventures. The reheated Aliens leftovers that made the film exciting in 1996 feel a little stale now, but director-star Jonathan Frakes nails the character grace notes and Trek optimism.

The Phantom

Another IP adaptation from a capable journeyman—Australia’s Simon Wincer—here of a comic-book hero known to generations via newspaper strips, newsagent shelves, and (in Australia) cheap showbags. Of the four notable post-Batman 30s-set pulp hero popcorn flicks of the 90s—see also Dick Tracy, The Rocketeer, and The Shadow—this is the most colourful and breeziest. In an interview with Den of Geek, Joe Dante—Wincer’s predecessor on the project—noted his version was intended as a parody and Wincer erred by playing it straight, which strikes me as a hip director punching down on a square director. If the film does err closely to Dante’s template, in form if not tone, then neither director was particularly ashamed of its many Spielberg derivations, from a rope bridge set piece ala Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom to a finale in a pirate cave ala The Goonies, all centred around a trio of exotic MacGuffins.

Dragonheart

This feels very much of a piece with Star Trek: First Contact and The Phantom, as a genre film that doesn’t play too rough, from a journeyman director (Rob Cohen), with a solid but un-exorbitant cast (Sean Connery’s dragon voice aside). Randy Edelman’s much-plundered score and the groundbreaking (now quaint-looking) creature digital effects give the film a touch of import.

One Fine Day

Two movie stars—George Clooney, Michelle Pfeiffer—falling in love over the course of a high-stakes day, two cute kids in tow. Like Jack, the film is pretty much what the packaging promises, and while Out of Sight in two years would be the guarantor of Clooney’s stardom—as well as mostly breaking his bobble head tic—he matches Pfeiffer at her already well-honed movie star game.

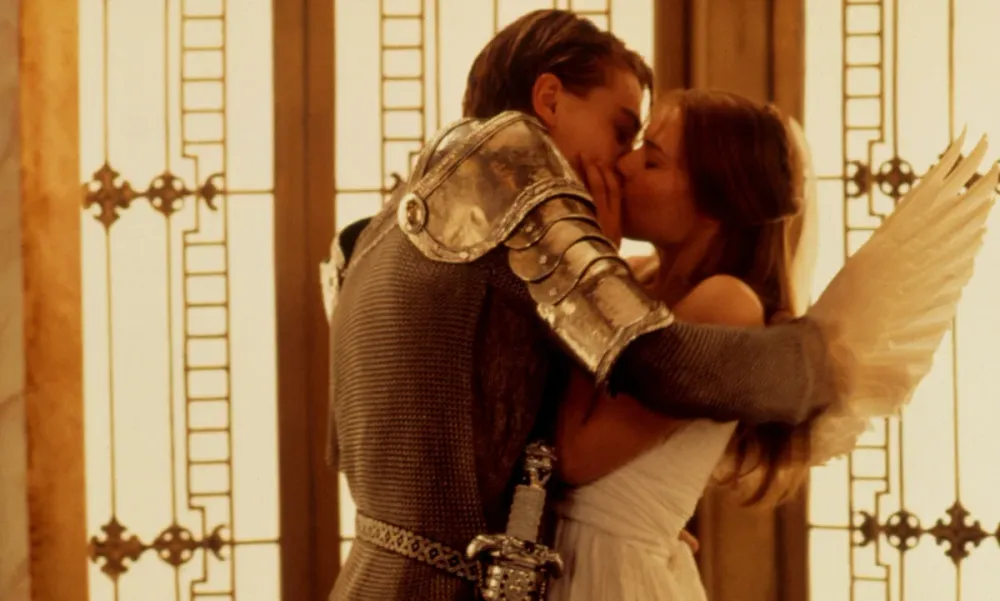

William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet

Baz Luhrmann’s sophomore feature and a quantum leap from the already confident craft and fully-formed sensibility of Strictly Ballroom. Moulding Shakespeare’s play to the recurring rhythms of his storytelling—ballistic and comedic opening, slow down to get swoony, then gradually racket up to a tragic denouement—Romeo + Juliet remains striking.

Evita

Also quite striking, Alan Parker’s final musical is, by virtue of its subject and stage source, a bigger and more bloated undertaking than the likes of Fame and The Commitments. But its casting coup in Madonna offers fascinating opportunities to riff on the mass manufacturing of star iconography.

Shine

Scott Hicks’s breakthrough and best film, which launched local industry veterans Geoffrey Rush and Noah Taylor on the world stage through some savvy awards season engineering. Though not undeserving of its acclaim, looking back at this biopic of pianist David Helfgott I’m intrigued by the absence of connective tissue bridging Helfgott as played by Taylor and Helfgott as played by Rush. A lot of impeccable craft and style and care is invested into making each individual scene pop, but the whole is predicated on the fallacy that experience X logically equals circumstance Y. Ultimately, all the hard work has gone into the trimmings and not the turkey, making Shine a series of quite splendid scenes and moments without a centre.

The rest: Oscar insiders and outsiders, rising talents, and a Travolta triple bill

Looking at the list above and then examining the broader sweep of 1996, I’m struck by what I didn’t see in theatres. I understand why I didn’t see The English Patient—which looked terribly boring—in theatres, though when I saw it on VHS I liked it and have grown infatuated with it over time. Anthony Minghella’s wartime puzzle box, piecing together the tragic backstory of a disfigured burns victim and his doomed romance, is elegant and impeccably made, with superb performances from Ralph Fiennes, Kristin Scott-Thomas, Willem Dafoe, and Juliette Binoche. But if you told me in 1996 that the dry-looking wartime romance not starring Sandra Bullock would not only be the better film but become a favourite, that would not have computed.

In 1996, the cinema where I saw new releases—the only one in our region—upgraded from a two- to four-screen complex. I distinctly remember seeing One Fine Day on one of the new screens, while Space Jam was one of the hyped releases coinciding with the expansion. The upgrade enabled more movies to play and more screening times each day, but even still many titles—not just art and indie films, but some mainstream ones as well—simply didn’t roll into town. For example, neither Escape from LA nor The Island of Doctor Moreau, both dogged by bad buzz, made it our way, though I was hankering to see both.

Escape from LA continued director John Carpenter’s patchy 90s, but it’s much more enjoyable than Memoirs of an Invisible Man or Village of the Damned and its tone & oddball ensemble feel embryonic of what James Gunn and Taika Watiti would deliver in their Marvel films. In contrast, The Island of Doctor Moreau is a rough, ropey film borne of a troubled production, and is too boring—even with Marlon Brando in white face paint and mumu accompanied by a 71cm sidekick—to sustain what could and should be a car crash-style fascination.

Of films that did screen locally, I’m puzzled I didn’t see The Rock or Broken Arrow, both heavily-hyped action releases of the year. The Rock is Michael Bay’s best film, stylish and propulsive and shorn of the bloat that would creep into his work immediately afterwards. It also launched Nicolas Cage as an action movie star, albeit transplanting the kind of manic put-upon characters he was playing in Honeymoon in Vegas and Trapped in Paradise into an action film context.

Broken Arrow was a very deliberate attempt by John Woo to emulate the style and rhythms of mainstream Hollywood action movies; the result is diluted Woo, but still executed with flair well above most of his peers and affording John Travolta some tasty scenery to chew on. 1996 was a big year for Travolta between Broken Arrow, Phenomena, and Michael, the latter pair serviceable programmers elevated by his presence.

I’m also puzzled that I didn’t see A Time to Kill (as a fan of John Grisham adaptations), Multiplicity (as a Michael Keaton fan), or Jingle All the Way (as an Arnold fan) in theatres, though none were great losses. A Time to Kill was director Joel Schumacher’s second Grisham film after the excellent The Client, falling between Batman assignments; in contrast to those three features—both good and bad—it’s a dreadfully boring film. Of course, the subject matter—an African-American father on trial for killing his daughter’s rapists—does not cry for a garish colourful approach, but on the flip side John Grisham and Joel Schumacher are not the guys I want or need grappling with racial tensions in modern America. Multiplicity and Jingle All the Way, meanwhile, are perfectly fine. The former effectively milks its star’s elasticity, while the latter effectively milks Arnold’s lack thereof.

I’ve touched on several of the Oscar winners and/or competitors of 1996: The English Patient, Shine, and Jerry Maguire. The Oscar year was notable as a year of indie takeover, where much of the prestige fare manufactured by the major studios failed to connect with the Academy but smaller, scrappier titles did. Those films included Sling Blade, an assured and thoughtful showcase for Billy Bob Thornton as writer, director, and star; Milos Forman’s The People vs. Larry Flynt, a meaty, tonally dexterous, and very entertaining biopic of the smut publisher; Breaking the Waves, Lars Von Trier’s ambitious, inventive, and taxing drama about a paralysed man who persuades his sheltered wife to sleep with other men; and Fargo, the Coen Brothers‘ black comedy about a crime gone terribly wrong in Minnesota, which has a lot of heart—in the form of Frances McDormand’s heavily pregnant police chief—to offset the filmmakers’ trademark style and misanthropy.

The list of major studio Academy-baiting sure things that missed out on nominations to these indie firebrands is a fascinating one. To be clear, some of these did earn craft or performance nominations, and the very idea of an Oscar snub is misguided, suggesting a coordinated effort by a diverse 10,000+ member organisation. Regardless, there’s an alternate 1996 Oscars where major nominees and/or winners included the abovementioned Michael Collins, Evita, and In Love and War; Rob Reiner’s serviceable race drama Ghosts of Mississippi; Barbra Streisand’s third and final film as director, the witty The Mirror Has Two Faces; Barry Levinson’s Sleepers, a starry-cast, well-crafted based-on-a-true-story-that-proved-bogus drama; Woody Allen’s entertaining musical Everyone Says I Love You, with a starry cast of questionable singing skill; and The Portrait of a Lady, Jane Campion’s cold and coolly received follow-up to The Piano.

With a Tombstone-level heritage cinema cast led by Nicole Kidman, John Malkovich, and Barbara Hershey, The Portrait of a Lady is perhaps Campion’s bleakest meditation on gender politics. It lacks The Piano’s novel setting, is heavily dialogue-driven, and is an unsentimental, resolutely no-swoon zone, turning a cold shoulder to The Piano’s complicated romanticism and eroticism. Yet even at its most baroque and remote, there’s much to admire about The Portrait of a Lady’s infusion of Gothic romance with feminist lament, and there’s a tactility to the film not typically seen in heritage cinema, nor in those other noteworthy adaptations of Henry James by the Merchant-Ivory team.

Whilst not as high profile as the abovementioned Oscar misses, I’m sure there was awards consideration for Italian masters Franco Zeffirelli’s Jane Eyre and Bernardo Bertolucci’s Stealing Beauty, as well as Bruce Beresford’s Last Dance, like The Chamber about a convict on death row—played capably by Sharon Stone in a deliberate effort to de-glam—and the ticking clock to prove their innocence.

While I use the term Oscar bait to characterise particular productions, it’s worth stressing that this is the domain of financing and marketing. Directors (mostly) don’t make films to win awards, but for a myriad reasons, including opportunity to tackle a piece of material they care about, to work in a particular genre or style, to film in a particular setting, or to work with specific actors. I imagine all those factors were behind Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet, as well as the historical import of adapting the full text of arguably Shakespeare’s greatest work to screen in its entirety. A directorial magpie, Branagh updates Hamlet’s medieval setting to a quasi-Russian aristocracy and mounts a lavish 70mm spectacle, pillaging cast, crew, moments, and motifs from epic cinema ranging from Dr Zhivago and Lawrence of Arabia to Gone with the Wind to Biblical epics. It’s an impressive achievement, absorbing despite its luxurious length, and like Henry V sees Branagh pressing into everything that makes him great as an actor and filmmaker.

Another impressive piece of theatrical adaptation, and to this day quite underrated, is Nicholas Hytner’s The Crucible. Adapted for the screen by Arthur Miller from his Tony-winning play, Miller and Hytner open up the play from its four-Act, four-location setting, making it feel more cinematic, whilst largely preserving the playtext. The result is a loss of the play’s theatrical claustrophobia and steadily mounting dread, but the trade-off is a fascinating fusion of heightened cinematic style, the rich and meaty theatrical text and texture, and Daniel Day-Lewis’s utterly convicted, bone-deep performance as John Proctor. These contradictory elements coalesce throughout and the conclusion feels especially transcendent, as Day-Lewis—spoiler—delivers Miller’s final lines fully immersed in character, seemingly believing he is a Salem farmer in the 1690s on the brink of being hanged for refusing to put his name to the lies that will save his life.

While Hamlet and The Crucible are generously-budgeted prestige pictures, there were a lot of lower-budget sneaky gems of different genres and styles throughout 1996. I’ll highlight seven. Firstly, Big Night, directed by Stanley Tucci and Campbell Scott, is a delightful and authentic-feeling dramedy about Italian restauranteur brothers sinking their skill and savings into a game-changing dinner party. The film has one of the all-time great final scenes: revisit here if you’ve seen it before; if not, watch the movie first. Another very Italian production is Abel Ferrara’s mob drama The Funeral, a mature and measured work from the oft-trashy provocateur.

Blood and Wine was Jack Nicholson and Bob Rafelson’s final collaboration, much better than Man Trouble earlier in the decade: a smart crime thriller with a strong supporting cast including Jennifer Lopez, Judy Davis, and Michael Caine. Lee Tamahori’s Mulholland Falls was the New Zealand director’s American debut and follow-up to the raw and compelling Once Were Warriors. A muscular and stylish 50s-set Los Angeles noir romp, it’s a little classier than Mobsters or Gangster Squad, a little junkier than Chinatown or LA Confidential, and has a stacked macho cast led by Nick Nolte.

Screenwriter David Twohy’s directorial debut The Arrival is a lot of fun; like Larry Cohen, the gifted genre artisan has a knack for wringing every inch of juice from a novel premise, and Charlie Sheen is in peak Charlie Sheen mode. Albert Brooks as actor-director is a cinematic blind spot that remains to be filled, but I have seen and very much enjoyed Mother, an acerbic but warm comedy co-starring Debbie Reynolds. Finally, Brassed Off, a British film about Yorkshire coal miners in a brass band facing unemployment, is a charming little gem and avoids the trap of Billy Elliott a few years later of presenting regional working-class Britons in a condescending light.

In addition to headlining Brassed Off, Ewan McGregor also popped up in Jane Austen adaptation Emma, with Gwyneth Paltrow charming and flexing her posh British accent as the titular matchmaker—Clueless savvily updated the same material the year before—and took the plunge (into the worst toilet in Scotland) in Trainspotting. Danny Boyle’s energetic take on ugly subject matter, with its virtuoso filmmaking and memorable soundtrack, pops from scene to scene and shares a similar vignetticism to Shine, but is more upfront about its style as substance.

McGregor and Boyle’s Shallow Grave collaborator Christopher Eccleston also had a busy 1996, headlining Michael Winterbottom’s tragic Thomas Hardy adaptation Jude but also two major television works in Hillsborough—about the stadium tragedy that claimed 97 lives and its aftermath—and Our Friends in the North. Across the Atlantic, Cameron Diaz—Boyle and McGregor’s partner in screwball caper crime in 1997—appeared in black comedy Head Above Water, grungy comedy Feeling Minnesota, and Edward Burns romantic comedy She’s the One; none particulary funny nor durable, but each with things to recommend, among them Diaz.

In addition to Hamlet and Romeo + Juliet, the 1990s rush of high-profile Shakespeare adaptations continued apace with Twelfth Night, an unremarkable but amiable adaptation from stage director Trevor Nunn with a talented ensemble; Looking for Richard, a very entertaining documentary on Richard III from Al Pacino—part meditation, part small group study, part talking heads, and part staging and recreation—that deepened my fondness for both the play and Pacino; and Troma’s schlocky Tromeo & Juliet, one of the company’s better productions.

One might be forgiven for assuming Tromeo & Juliet was a mercenary cash-in on Romeo + Juliet; it actually debuted at Cannes five months before Luhrmann’s film’s release. However, the long tails of other 90s successes can be seen in 1996. Notably, the continuing tail of Pulp Fiction is evident with two black comedy crime thrillers with stacked casts, Two Days in the Valley and Albino Alligator—both fine, the latter directed by Kevin Spacey—and Robert Rodriguez’s spirited Tarantino-scripted romp From Dusk Til Dawn.

Whilst this was a year between Batman films, that franchise’s continuing influence was evident in Olivier Assayas’s Irma Vep, an intriguing French film about filmmaking with Maggie Cheung playing herself as an imported star cast as the titular latex-suited heroine; Assayas and Cheung knowingly reference Michelle Pfeiffer’s role in Batman Returns. The inferior sequels The Crow: City of Angels—a really quite ugly and gnarly film—and Darkman III spun off from their excellent originals.

Finally, Steven Seagal appeared in films continuing the buddy cop movie tradition—The Glimmer Man—and the “Die Hard in an X” tradition—Executive Decision, aka “Die Hard in a plane”. However, Seagal pulls a Janet-Leigh-in-Psycho early exit in Executive Decision, handing the heroic reins to Kurt Russell. The film was the directorial debut of Stuart Baird, the wizard editor and Warner Bros fixer I’ve mentioned a few times in this series—see also The Last Boy Scout, Tango & Cash, Demolition Man, Maverick et al.—who over three directorial efforts would prove a much better editor.

Elsewhere in the action genre, Maggie Cheung’s frequent co-star Jackie Chan continued to carve an international profile with Jackie Chan’s First Strike, shot partly in Australia. Then-husband-wife team Renny Harlin and Geena Davis do penance for Cutthroat Island with The Long Kiss Goodnight, a very enjoyable actioner that’s more in Harlin’s wheelhouse and bolstered by a whip-smart dumb script (if that makes sense) by Shane Black. Van Damme starred in another Hong Kong action director’s Hollywood debut, Ringo Lam’s Maximum Risk; Dolph Lundgren headlined Russell Mulcahy’s very stylish Silent Trigger; and Stephen Baldwin and Laurence Fishburne riff on The Defiant Ones as manacled fugitives in Fled.

Horror titles included Peter Jackson’s The Frighteners, Dario Argento’s The Stendhal Syndrome, teen-centric The Craft, the trashy Freeway, and Stephen Frears Mary Reilly, which retold the Jekyll and Hyde story from Jekyll’s housemaid’s perspective and afforded Julia Roberts’ another stab at an Albion accent. Additionally, Wes Craven’s Scream ushered in a slasher film revival and initiated a new generation into the genre.

Comedy-wise, the genre continued to be driven by marquee names, with the occasional adaptation of IP (the clever A Very Brady Sequel) or combo of star plus IP (Steve Martin in Sergeant Bilko). Star vehicles of the year included The Associate (Whoopi Goldberg), Carpool (Tom Arnold), Spy Hard (Leslie Nielsen), The Birdcage (Robin Williams, though Nathan Lane was the film’s breakout), Down Periscope (Kelsey Grammer), Happy Gilmore (Adam Sandler), Black Sheep (Farley and Spade), and Bio-Dome (Paulie Shore): a bag of trash and treasure, of which The Birdcage, Happy Gilmore and—come at me—Bio-Dome have aged the best. Ensemble-based comedies included family-friendly House Arrest, David O’ Russell’s acidic Flirting with Disaster, Christopher Guest’s mockumentary Waiting for Guffman, and the likeable The First Wives Club.

Sports comedies were also big in 1996, the sub-genre yielding Kingpin, The Great White Hype and Celtic Pride (both featuring Damon Wayans), and Tin Cup, a delightful rom-com from sports movie poet laureate Ron Shelton pairing Kevin Costner and Rene Russo between Costner’s pricey post-apocalyptic films of 1995 and 1997. At the more serious end of the sports movie spectrum, documentary When We Were Kings explored the famous Rumble in the Jungle between Muhammad Ali and George Forman. Similarly, the puerile animated comedy Beavis & Butthead Do America was flanked by the earnest Disney release The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, like Pocahontas aspiring for classiness at the expense of fun.

Demi Moore lent her voice talent to both Hunchback and Beavis & Butthead, but gave and bared all for Striptease. A media cause de célèbre—for the subject matter, Moore’s nudity, and the actress’s handsome $12.5 million payday—Andrew Bergman’s comedy drama is really too slight and middling an affair for the disproportionate weight of media attention upon it. David Cronenberg’s clinical Crash was a meatier work and another cause de célèbre, though as a Canadian art film on which no actors were paid $12.5 million, the tabloids did not breathlessly follow production. Lesbian drama Fire also caused a stir in its home country India when released there four years later.

As seen with action and comedy, stars came and went, exploded and flamed out, but still carried sway above properties in 1997, with the poster for Striptease—Moore in her birthday garb—the nakedest illustration of this. Similarly, stars sold—and in some cases didn’t—legal potboiler Primal Fear (Richard Gere, though Edward Norton broke out), rom-com Up Close and Personal (Robert Redford and Michelle Pfeiffer), political drama City Hall (which looked—and was—rather dreary, but with Pacino in City Hall someone would certainly be yelled at), boarding school drama Boys (Winona Ryder), and noir thriller Heaven’s Prisoners (Alec Baldwin, attempting another franchise after Jack Ryan and The Shadow), their faces and little else emblazoned on their posters.

Stars also featured prominently on the marketing for war procedural Courage Under Fire (Denzel Washington, Meg Ryan) and medical thriller Extreme Measures (Hugh Grant, Gene Hackman), with Ryan and Grant attempting new genres, the former quite capably, the latter much wobblier. While Meryl Streep had a shaky stretch in the 90s—not headlining as prestigious fare as the 80s nor as populist fare as the 2000s—she’s nonetheless central to the marketing of the average and largely forgotten Marvin’s Room and Before & After.

I have plenty of VHS store memories peppered across eight stores that operated around my town at different points of the 1990s. One of those memories, drilled in by TV commercials, was the Video Ezy movie guarantee: a promotion where there were so many copies of a particular title that it would become a free rental if not in stock. The three movies I remember from this promotion were Scream, Last Man Standing, and The Fan.

Tony Scott’s baseball thriller has, expectedly, a ton of style and gloss as well as sturdy leads in Robert De Niro and Wesley Snipes as stalker and stalked respectively. But it’s a bit like tasking a master carpenter to assemble an IKEA table: for all the craft and precision and burnish, it’s still an IKEA table. Scott and James Foley could have swapped directorial chores on this and Fear—another generic stalker movie with Mark Wahlberg obsessing over Reese Witherspoon, to dad William Petersen’s chagrin—and neither film would be significantly better or worse.

Brother Ridley Scott, meanwhile, delivered White Squall, his second and last nautical adventure film after 1492: this particular sub-genre defeated him, as it clearly pummelled Harlin and Reynolds & Costner in the same era. There are Ridley Scott films I love or like, ones I dislike, and ones I don’t have much opinion on, a camp White Squall falls into. But I love that Scott exists, that he had a second wind with Thelma & Louise after a patchy mid to late 80s, followed by a third wind with Gladiator after a patchy 90s, and that this third wind continues and he’s become a sort of brusque John Huston type making muscular, large-scale historical and adventure romps of varying quality at exotic locations with first-class actors.

Working at a smaller scale, a handful of new directors—some of whom would command their own military-level budgets and casts & crews within a few years—broke out with smart, arresting debuts. While it might be my least favourite of his films, Bottle Rocket is instantly recognisable as a Wes Anderson film, the director arriving almost fully formed. Ditto for Bound, the Wachowski Siblings’—then Brothers’—debut feature, a nimble thriller where Gina Gershon and Jennifer Tilly are lovers who cross Tilly’s mobster husband. As their work and identities have evolved, Bound—at one point an anomaly in their filmography—has proven a Rosetta Stone for much of what followed.

Hard Eight doesn’t really hint at the ambition, eccentricity, and greatness that would characterise Paul Thomas Anderson’s subsequent body of work, but several of his preoccupations and utility players are introduced here and it’s an impressive, stylish debut. Finally, while technically his sophomore effort, Swingers became the calling card for Doug Liman as well as writer-star Jon Favreau.

In addition to Stanley Tucci, Campbell Scott, and Billy Bob Thornton making their directorial debuts, another pair of very different actors—Tom Hanks and Jean-Claude Van Damme—made their directorial debuts with pop musical That Thing You Do and ropey adventure The Quest respectively, while Bullet, teaming Mickey Rourke and Tupac Shakur, was one of three uncredited scripts written by Rourke.

I occasionally touch on telemovies and event miniseries—like Hillsborough and Our Friends in the North above—and a few more warrant mentions: the Ted Danson-starring, family-friendly Gulliver’s Travels; Moses featuring Ben Kingsley as the titular leader of the Exodus and a pair of Draculas in Christopher Lee and Frank Langella; Rasputin featuring Alan Rickman as the Russian Machiavel; and the Americanised Doctor Who featuring Paul McGann’s debut and swansong as the Eighth Doctor. None of them rival Breaking Bad as great television, but all are memorable, with the latter three showcasing great villain performances from Langella, Rickman, and Eric Roberts, all bringing glazed ham to the party.

Three Australian releases of 1996 derived from stage works. Dead Heart, a dramatic thriller grappling with uneasy relations between Indigenous Australians and white authorities in a remote community, was adapted by Nick Parsons from his own play and has the meat and texture of a sturdy piece of theatre. Brilliant Lies, adapted from David Williamson’s play about sexual harassment and office gender politics, is executed with skill by Richard Franklin and a talented cast including Anthony La Paglia and the Carides sisters. Mark Joffe’s Cosi, about patients at a mental hospital staging Mozart’s opera of the same name, updates Louis Nowra’s play from the 1970s to 1990s, eliminating its counter-culture and anti-war themes, but on the flip side creating sequences—including a montage of the inmates’ performance—that would not be feasible in a stage production.

Ben Mendelsohn features in both Cosi and Idiot Box, David Caesar’s angry drama about TV-addled bogans turning to crime. The wonderfully expressive Miranda Otto, meanwhile, is the MVP of Love Serenade, Shirley Barrett’s wilfully offbeat Camera d’Or winning film about small-town sisters enchanted by the arrival of a new radio host, while Judy Davis dominates the political black comedy Children of the Revolution, about an Australian communist who has an affair with Stalin before his death and gives birth to Stalin’s son in Australia, who proceeds to become a polarising political leader.

Also hailing from Australia, Dating the Enemy sees sparring couple Guy Pearce and Claudia Karvan switch bodies; gender-bending fish-out-of-water comedy ensues. Clara Law’s Floating Life is a perceptive study of Chinese diaspora, where humorous vignettes about culture clash give way to drama and melancholy as one-dimensional characters reveal new dimensions. Similarly, Nadia Tass’s Mr Reliable begins as a droll comedy of errors with an accidental hostage situation, then gains dramatic heft as the stakes escalate, tapping into the pro-battler, anti-police, anti-authority sentiments that pervade much of Australian cinema.

Finally, Love and Other Catastrophes, about the trials and tribulations of five university students, is one of those films where you can almost pinpoint the month, date, and day of the week it was shot: it’s a film both by and about the very kids that Quentin Tarantino and Kevin Smith sent scurrying to film school. Budgetary constraints prevent the film from conveying the genuine swarm and bustle of a lively campus, and it exhibits tell-tale signs of a young filmmaker in its blemishes, pretensions, and self-deprecations. But it’s also spunky, charismatically cast and acted, and both preposterous and deeply earnest in its trivial pursuits.

I clocked 151 films from 1996 for this piece, a large number of movies to wrangle into a narrative. Therefore, I’m going to close with a rather inelegant dump of titles, mostly good, that didn’t slot in logically elsewhere in this article: Stuart Gordon’s weirdo working-class sci-fi comedy Space Truckers; David Koepp’s sweaty three-hander psychological thriller Trigger Effect; Spike Lee’s Get on the Bus, a road movie with a deep bench of character players; thoughtful biopic Basquiat with Jeffrey Wright as the titular artist and David Bowie as Andy Warhol; and French thriller The Apartment teaming Vincent Cassell and Monica Bellucci.

For the record, some notable films of 1996 that I have not included because I haven’t seen them: Secrets and Lies (the biggest ongoing omission of the year), Night Falls on Manhattan, Lone Star, Surviving Picasso, The Evening Star, Grace of My Heart, Beautiful Girls, Diabolique, The Juror, The Secret Agent, The Truth About Cats and Dogs, Mother Night, Some Mother’s Son, High School High, Barb Wire, Flipper, Pusher, Dunston Checks In, Matilda, James and the Giant Peach, Kazaam, The Preacher’s Wife, Bulletproof, Bed of Roses, To Gillian on Her 37th Birthday, Mrs Winterbourne, The Pallbearer, Two if by Sea, Citizen Ruth, Tales From the Crypt: Bordello of Blood, and If These Walls Could Talk.

If you’re still here, thanks for enduring and see you back here for 1997, when the Titanic sails and sinks, two Australian talents break through internationally, Robert Carlyle bares all, gigantic sequels disappoint, shiny new studio DreamWorks launches, Nicolas Cage cements himself as an action hero, the volcano movie war erupts and sputters, and Danny Boyle misfires adorably. Til then …