Over on Letterboxd, I’ve been quietly maintaining a personal list of lost or unavailable Australian films. Since I started the list a few years back, one film that sat at the top of the list was Daniel Nettheim’s Angst, written by Anthony O’Connor and starring Sam Lewis, Jessica Napier, Justin Smith, and Abi Tucker.

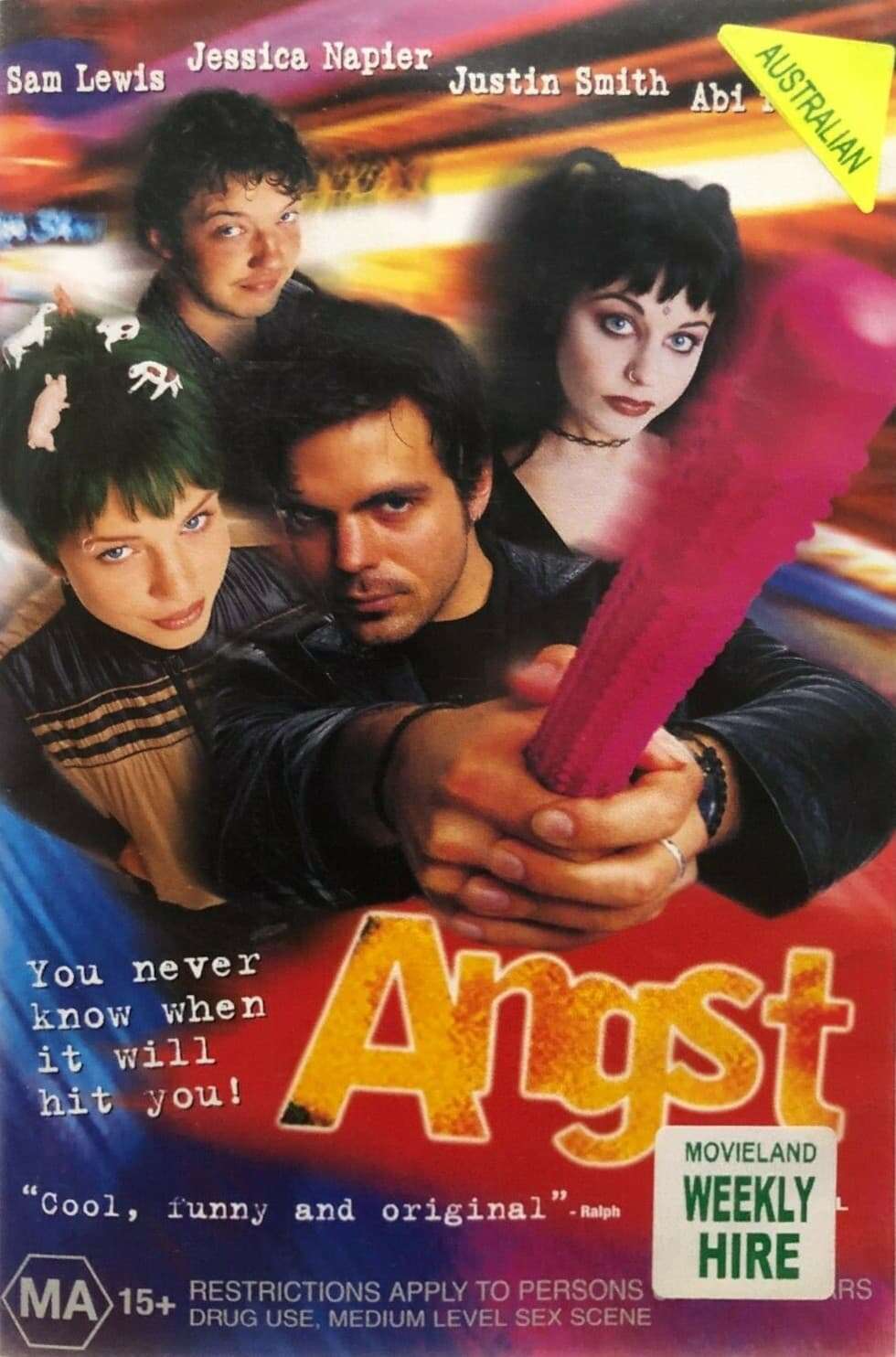

It says a lot about the underground nature of the film in that the image used for the Letterboxd profile is a photo of a VHS copy of the film sporting the neon yellow genre label proudly proclaiming this is an AUSTRALIAN film, while the Movieland Weekly Hire sticker in the bottom right corner partially covers the MA 15+ rating, but not the quote from the review from Ralph magazine. A real sign of the era.

There’s every chance that this photo of the VHS cover is from one of the many stolen copies of Angst that made the film the most stolen videotape in Australia. It’s also one of the rare films to feature an actor brandishing a bright pink dildo on its cover.

Angst is peak turn of the millennium stuff, sitting comfortably alongside films like Clinton Smith’s Sample People or Emma-Kate Croghan’s Love and Other Catastrophes, or even the likes of the long unavailable and dormant (yet still fondly remembered by me) ABC series Love is a Four Letter Word. There’s a whole library full of films from that decade or so period – Garage Days, All My Friends Are Leaving Brisbane, The Secret Life of Us, to name a few – that spoke to an undervalued slice of Australiana. The twenty-somethings finding their place in the world, seeking an avenue for their voices to be heard, valued, and understood.

Angst sits firmly in that space, telling the story of four people floating in and out of the lives of one another. A group of roommates existing in the flurry of Kings Cross, Sam Lewis’ Dean works at a video store, while Justin Smith’s Ian is trying to get over his ex, and Jessica Napier’s Jade can’t seem to get rid of her ex-in-waiting. Meanwhile, Abi Tucker’s May is as perfect an example of goth girls of that era.

Watching Angst some twenty-five years on from when it was released is a charming experience. The artefacts of the era standout in a way that they may not have been as clear back then; namely, the inspirations from filmmakers like Kevin Smith, whose Clerks transformed the way independent filmmaking occurred back then, not just on a financial level, but also in a way it invited people to tell versions of their own lives on screen.

In some way, Angst is a cultural curiosity, existing as an example of what ‘back then’ was like, but it’s also a mighty entertaining flick to watch, with the lead four actors having superb chemistry and screen presence that feels organic and realistic.

Unavailable for far too long, Angst made a triumphant return at the Inner West Film Festival in 2024, and has now been re-released on physical media with a DVD that contains an array of great special features. It’s also available on demand to watch. Given its life as a notoriously thieved disc, here’s hoping it gets a chance to reach a new audience, or reconnect those from back in the day who loved the film back then.

I caught up with writer Anthony O’Connor on the release day of Angst on DVD and streaming to talk about his journey into writing scripts, what the production was like for the film, how the dire box office for the film felt at the time, and what it meant for the film to get a new life on VHS. We also chat about the still live website for the film too.

Screening or Streaming Availability from JustWatch:

Congratulations on this Angst physical release day.

Anthony O’Connor: Thank you. It's been really interesting to revisit a film that is a quarter of a century old now. It's older than that for me, because I started writing it when I was about 18, which is a long time ago; we're talking 30-some years. Watching it now it feels like it was written by a different person, which in a lot of ways it was, but it has been really nice to revisit it.

It's great for it to be able to be seen by an audience, because the point of a film is to be seen. It doesn't necessarily need to be like a blockbuster or a kind of Avatar situation, but you definitely want an audience to watch the film, particularly the intended audience, the people that you were trying to reach. And when that doesn't happen in the case of Angst because of both business and technical issues, [then] it's really disappointing to watch your film become almost lost media. And to see that change has just been really, really gratifying.

Before you wrote Angst, you tried your hand at horror scripts. I want to put people into the mindset of what it was like being a film nerd in the 90s and seeing all the different kinds of stuff that were coming out. There were a whole bunch of different things that were moving along in film during that era - horror, Kevin Smith, Tarantino, all that kind of stuff. I'm curious about what your mindset was like in trying to find your voice through horror scripts and then navigating it to writing a script like Angst.

AO’C: I've been a horror nerd from a single digit age, from before I could watch horror movies. I used to go to the video shop with my parents and just be fascinated by the covers. I would just stare at them for as long as they'd let me stay. Of course, it was many years before I got to see the actual movies, many of which were nowhere near as good as the covers. I used to go home and make up my own stories about what happened in them and whatnot. Those garish plastic covers really stuck with me. I think the first two that I was finally allowed to see were Creepshow and American Werewolf in London. I'm not sure which order I watched them in, but those were the first two and I just adored them. I think they have aged quite well. That began a love of horror that continues to this day.

For a horror fan, and particularly in Australia, the 90s weren’t a good time. It was not a good place or time to be a horror fan. Horror was considered by so many to be this real kind of ghetto genre, there was something wrong with you if you liked it. They would do the thing that people do when they just don't like something and they wanted to make a moral point about it. It's like they would compare every horror film to the worst example of the genre, like the most exploitative, the most sleazy, they're like they're all like that, which, of course, we now know is nonsense, thank God. But at the time, that was a really prevalent attitude.

That attitude continued in the kind of films that were getting made in Australia, and certainly the way that we showed them. Queensland banned so many horror films. The ‘Banned in Queensland’ sticker at the video shop was always a badge of honour for me. George A Romero's Day of the Dead was a really notable example of something that was banned in Queensland. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 didn't come here until relatively recently. I'm not even sure it's legally allowed there.[1] You can get around that now, obviously with ordering online.

There was a real sense that horror just wasn't for us here in Australia. I remember distinctly early on, having a meeting at Fox where a very earnest and pleasant but demonstrably wrong producer told me there will never be a big Australian horror film and there will never be a mainstream zombie film. ‘These things just don't happen so stop trying to pitch them, because it's never going to happen.’ I was a huge zombie nerd back in the 90s before it became a thing, so it was really frustrating to have people not understand gleefully what you loved about the genre and what you were trying to do.

It didn't help that the screenplays I wrote then were absolutely crap. I mean, they were like a lot of first-time writers for screenplays very self-conscious, derivative versions of the films they love. For me, it was lots of American Werewolf stuff, lots of kind of Cronenberg stuff, but with none of the intelligence or wit or perceptiveness that made stuff so good, particularly Cronenberg. It was like I understood that heads exploding are cool, but not why a head exploding is actually a combination of a bunch of different themes and whatnot. People were nice, but you could tell that it's like ‘you can write, but this is all crap that you're doing.’ Again, this is 30 years ago. I'm sure I wasn't as sanguine as I would have liked to have been about that, but eventually I took on board that perhaps I should try something a little more in the ‘write what you know’ wheelhouse. The problem being is that I was 18 and I didn't know fucking anything. That was kind of where the seeds of Angst started.

But yeah, 90s horror fans were done dirty, it was not a good time. The 70s and 80s were fantastic, and in the 90s, there was a real move against us. There was a lot of censorship. There was a lot of social pressure to avoid these sorts of films. I think it was the OFLC at the time who was also banning or cutting films in the most arbitrary ways. I remember Henry Portrait of a Serial Killer had a bunch of scenes just trimmed because of ‘a general tone’. What does that mean? The tone is meant it's Henry Portrait of a Serial Killer. The tone is meant to be that you can't censor a tone. What the hell is that? I'm still angry after 30 years. As you can see I've moved on.

I want to talk about then writing Angst. You blast out these horror scripts, and then you give them to other people, and they say, ‘it's terrible’. Then you have to learn how to rewrite and rewrite and polish it and shape it into something workable. As you said, you start writing it at 18 years of age, so it wasn't like you were shooting that same year, so it took a bit of time to get it polished. It's teaching you discipline to actually do that. How did you get into that mindset of getting the discipline to get the script to a state that would work?

AO’C: I'd love to say that it was just discipline. I think it was kind of an overweening passion as well, because for all my lack of practical talent in the area, I had such a drive to tell stories. I always had, even when I was very young, I used to draw and I always had that sort of burning urge to create. So the key then was to A) learn technique, and B) learn good work practice. The technique I learned; the work practice, I'm not sure. It was quite kind of unwieldy and inconsistent a lot of the time.

There's a real stop start nature to that vibe as well. Because once I'd started writing what was then called Angst for the Memories – apologies for the pun – and then became Angst, it was stop-start, because people liked it, and then they cooled on it, and then they liked it, then they cooled on it. Different people had different inputs, so I had to be prepared to kind of stop-start.

The key thing for me was working on other stuff as well. I worked at a company called Brilliant Interactive Ideas, which kind of was a precursor to Telltale Games type games, choose your own adventure style games. Choose your own nightmare was one of the series that I did. You can find them on YouTube. There's one I did called How I Became a Freak that got a cult following from teens or tweens at the time who had watched these things thinking they were kid appropriate. I had snuck in all this horrible Lovecraft and Junji Ito stuff that they're reacting to.

Having multiple projects on the go meant that I could then, with a bit of objectivity, go, ‘wait, if this didn't work here and I need to have less dialogue here, then maybe Angst should also have less dialogue here, and maybe this should happen faster.’ There was a lot of on the ‘on the job, practical experience’ that really helped me hone my craft and technique. I freelance script edit for people now, and one thing I always say is to have more than one project on the go, because if you relax the muscle that's controlling Project A, then project B gets better, and vice versa, because start tootling away on Project B, and then that helps that one. I think it was about having multiple irons in the fire. Being able to see where my attention was drilled into really helped me along the way in a way that I didn't realise at the time. Like, I was just annoyed that it was taking so long, but in retrospect, it was the best thing.

I think developing a script over time, particularly when you have other people read it out in a kind of table read scenario, which I did with a class with a guy called Steve Worland, is hugely helpful. When you hear other people say your words, sometimes it's like, ‘wow, this was god awful. I’ve gotta work on that entire section.’ Or, conversely, ‘hey, that actually works. That's a good moment. I can see if I can build on that.’

Going back to the vibe of that 90s aesthetic, there’s Tarantino-esque films, there were the horror films trying to copy Scream. Then probably the most pivotal ones were the lo-fi indie films, following the likes of Soderberg, Clerks, Linklater. I think Clerks was transferable to a lot of places, because the place it represented was so familiar to a lot of places. Was that an influence for you with Angst?

AO’C: Clerks, for me, was like a miracle. I can still remember seeing it at the Verona in Paddington with a bunch of friends, all of us either stoned or drunk or whatever we did then. We'd heard it was good, but it wasn't like now, where you can watch trailers online and know everything about the film before you see it. And it just blew the back of my head off. I just thought it was so smart and so witty and so knowing and wry and human. I remember seeing a Kevin Smith interview, and he talks about watching Slacker and having that experience, I had that experience with Clerks. I was just, I don't know if this is a movie, but whatever it is is extraordinary. I remember thinking, ‘I want to get some of that into it. I want to be able to do that to the degree where it's Smith-esque without just being a rip off of Clerks.’ Because that was always obviously a concern, we had similar jobs and all that kind of stuff.

Clerks was really a revelation for me, as for a lot of films were at the time. Woody Allen films and Hal Hartley films and Jim Jarmusch, anything that kind of focused on a lot of people walking and talking and talking about life and smoking and drinking coffee was very much in my wheelhouse, because that was life then. We were these absurd 18- or 19-year-olds talking about life like we knew a fucking thing, because that is, I guess, the first time that you are treated like an adult. You kind of do see the world as this new playground, and you're trying to figure it out, and you're fairly convinced that you haven't figured out – of course, you don't at all. The point of stuff like that is that you're trying to make sense of everything and to find your place in it and that's very appealing for a young person.

And look, it’s very appealing looking back too, there's a real nostalgia riff of a lot of those films. I still love Clerks. I still think it’s a really smart, whip smart film. It's probably his best film, to be honest. I’m not a fan of much of his more recent stuff, but he did get better at directing and visualising. There's a purity to Clerks that that still resonates.

I haven't revisited it in a long time, but the memory that sticks with me of it is that it's a film that feels true because it feels like it's about people who genuinely exist. It’s almost documentary like, and while there is an obvious artifice to it, it’s shining a light on people who are doing what they would probably be doing otherwise, just in a heightened way. I look at a whole bunch of Australian films and TV shows at the cusp of the millennium, the late 90s, early 2000s – The Secret Life of Us, Love and Other Catastrophes, All My Friends are Leaving Brisbane – these kinds of films are about vibes and feelings and presenting a slice of Australiana that wasn't really getting shown on screen much at all. Angst is part of that.

Then, outside of Two Hands, we don't really get to see King's Cross from that era on screen all that much. Especially outside of the criminal aspects or anything like that, there's nothing really on film or TV from that time that is about the people who were living there, working there, and calling it home. And so it's that slice of life which feels authentic in Angst. It's documentary-like in some capacity, but not really. Was that something that was on your mind when writing Angst? ‘I don't get to see this slice of the world on screen. I've got to bring this level of “us” into the world.’

AO’C: I think it was a preoccupation of mine, but it was also a preoccupation of the 90s, as I'm sure you remember, that authenticity and truth were real catch words for that generation growing up for Gen Xers like me. We had so much corporate slop over so many years that kind of defined the young experience or the working experience in ways that were so truth avoidant and so edgeless and so devoid of anything authentic, that anything that had the smack of authenticity about it, like Clerks that despite looking like it was shot for 10 bucks and in black and white that was crappy and grainy, was hugely appealing.

And all those Aussie films you mentioned, they were all trying to say, ‘this is this slice of life for us. This is what it is like here.’ All the way along, I wanted that to be the case as well. Obviously, the gags heighten things and exaggerate things for comedic purpose, but the basic premise of everything had to feel real. Not every second in the Cross is a stabbing or a shooting or a home invasion. Not everyone's off their tits on heroin the whole time, although God knows that was a lot. People do navigate their way through the strange land that was King's Cross. If you worked in customer facing jobs back then, you faced a lot of gronks and psychopaths and just insane shit all the time, and that was just part of your day. That was just what you did. So yeah, the authenticity was a huge part of it.

And the authenticity of what it was like to be a very specific type of nerd as well, like Clerks, it was all comic book nerds and Star Wars nerds, they never quite got the treatment that horror nerds got; horror nerds were freaks and weirdos, and not in a good way. This is before ‘Freaks and Weirdos’ became like the number one show on Netflix. So, yeah, I wanted to really drill into what it felt like.

When Dean is on his net date accidentally with two 12-year-old girls, one of them says something about horror movies, ‘isn't there enough violence in the world?’ I heard that so many damn times. ‘What do you like?’ ‘I like horror movies.’ ‘Isn’t there enough violence in the world?’ Which is such a disingenuous take. It’s like, if you like dramas, ‘isn’t there enough drama in the world?’ Why don't we just have porridge flavoured bland, beige experiences, instead of having anything spicy? That line I got a lot, ‘isn't there enough violence in the world?’, and it’s like there are cool zombies and allegorical horror tales and cathartic splatterfests, these are all valid forms of expression. You’re allowed to not like them, what you're not allowed to do is make everyone who does like them feel like shit. What a weird thing to do. I wanted to kind of get across that this is what it feels like when you say that you absolute frauds.

We got some really good reviews. Two that I remember really well. One was David Stratton, who gave us four out of five, which blew me away. Margaret was not a fan. Megan Spencer from Triple J at the time, she said, ‘it is so accurate being this very specific type of nerd, and it feels exactly what this feels like.’ I was like, thank you Megan. I went to a screening of I think it was The Devil’s Rejects years ago, and believe it or, the people behind me were Megan Spencer and David Stratton. I wanted to thank them both for their lovely review, and I was too shy and I didn't. I'll never forget those two reviews because they meant so much to me. At the time, pre-internet and whatnot, you basically had the reviews that were out in the paper and The Movie Show, and that was the lot. Having some feedback that it meant a lot to people was really nice.

That was the mission statement, that it needed to feel authentic and it had to feel true, obviously the laughs have got to be big as well, but this not be an exaggeration and not a kind of bevelling of the edges of what it felt like to love something that people thought was at the time wrong or morally suspect.

I want to quote from The Movie Show review for a moment. David gives a spiel about what the film's about, and Margaret says “This is for the 15 to 25 age group, and I don't qualify.” She gave it two stars, so it's not exactly the most positive review. She clearly hadn't stepped into her give ‘Australian films an extra half star just because they're an Australian film’ era at that point.

AO’C: She also said people don't talk like that. That was a big thing. ‘People don't talk like that.’ I've met her since then, and we're cool, I'm very fond of her and I think she's a great critic. But Margaret mate, I can assure you, people do talk like that. There's a bunch of us and we talk like that.

Then there’s the time capsule aspect of Angst. I found it fascinating how you’ve captured the turn of the era in the film. There's the discussion about the new big video store that's opened up, but then there’s this recognition of the future state of the characters, of Dean realising that the old guys on the street, the homeless people, that could be him in the future. That's kind of sad to see. The lines are delivered in a ‘shit, if I don't do something about my life, then this is how I'm going to be’ kind of way, which is a fascinating thing to embed in a film that's quite light for the most part. Then there’s the cultural artifacts of what Kings Cross was like too. Were you conscious of this time capsule aspect of it when you were writing it?

AO’C: Andrew, I would love to say that I was. We had a dial up modem, because that's what we used at the time. We had the concept of internet dating being this thing that only losers did, because that was of the time. We had VHS, because I remember thinking that DVD was probably a flash in the pan, so again, not exactly on the ball with that one.

I think capturing an era realistically is always going to make it a time capsule. We happened to capture an era that was right on the cusp of a huge change. I started writing it somewhere in 94-95, sold it in 95 and then developed it until 99 when we shot it. I think a way the development time was good, because if it had come out in 96 it would not feel anywhere near as much of a time capsule, I think, because that would be much more 90s. But this was right on the cusp of everything changing. The internet went from something that obsessive Star Trek fans and weirdos used, to how we literally communicate and do all the stuff that we do. VHS was about to pivot to DVD, but more importantly, it was about to pivot to something else entirely, which was physical media being such a small component compared to the juggernaut that it was at the time.

And King’s Cross, this wild and woolly kind of environment that we literally needed to hire a gangster to keep it safe during the shoot in the exteriors in the Cross, it has become kind of a strip mall now, it's such a Bougie [area] or dull, the Bougie sectors are nice, the dull sections are kind of depressing. You could not walk in the street without being offered sex or drugs or being punched in the head, sometimes, all three. Now, I mean, there are still strip clubs there, and I'm sure, if you looked hard enough, you could find drugs for sure, but the out in the open sense that if you were there, and you didn't like any of that stuff, then that was your problem, like, they're not going to clean this stuff up. This is just what the Cross is. If you didn’t want the pig, don’t run to the market. Now, it’s been cleaned up and everything's pushed into where it is, into alleys and side streets and subways. Everything has changed.

The monorail is gone. We had a lovely monorail in Sydney, and that went soon after. So all these things that were just part of life, that was just a normal part of doing business, either changed dramatically or destroyed entirely. It's a real edge of whatever the change was from the 90s to the 2000s. It captures that accidentally.

RIP the monorail. I think Angst and Two Hands, and maybe one or two other films are the cinematic representations of that, which is quite something.

AO’C: Yeah, I would literally get on it because it was cheap and it was a great place to talk because you see a bunch of places. It was good, in general. I mean, it wasn't most useful public transportation, but I loved it.

Let's swap over to talking about the cast as well. Alongside Daniel Nettheim, how did you go about getting the right people on screen?

AO’C: I was very lucky in that I was allowed to come to a lot of the casting sessions. I would read against people we had coming in. We saw I think it must have been in the hundreds. We needed dynamic between people. At one stage audition, we saw Matt Newton and Joel Edgerton. Joel was going to be in it for a while, but then he had, I think it was the Sydney Theatre Company Bell Shakespeare commitments.

Because it is such a dialogue heavy film, and such a vibe film, the casting process was genuinely exhaustive. We would hold all these kinds of events and get so many people in, and a lot of people, while they were fantastic, they just weren't quite right for how we wanted the role to be. I was not the decision maker, at this stage the script was locked or mostly locked off, and so if you're lucky, the writer is listened to but is not the driving force at this stage. They would hear what I said, but this was mainly Daniel and Jonathon Green's party, the director and producer, respectively.

It was fun. It was really in depth. It was really engaging. I was delighted with the cast we got. Still to this day, you look back at the way they play it, and to me, they feel even better now. Maybe it kind of hits my ear different, but now, watching it years later, I think everyone does a great job. I'm particularly taken with the core three, and the dynamic they have. They play up each other beautifully.

You've got a cameo as Toaster Junkie. What was the decision behind playing that character?

AO’C: I can't remember specifically why. I think we always wanted me to have a small role in something, because I'm an okay actor. For a while we were talking about me for Logan, who is Dean's rather sleazy co-worker, but then we got Jonathan Devoy, who was really great in that role.

Toaster Junkie gets a few lines, and he gets to be funny and odd and quirky, and I could do that. I had cheek bones and had very, very pale skin back then, like more pale than now, and they told me not to wash my hair for a few days or a week, I can't remember, and then just kind of slump on set wrapped in a beanie. I’d have that nasal kind of voice. As a guy who worked in a video shop would often have to politely decline junkies attempting to join or attempting to rob the place, so I was well versed in the look and feel of those characters.

At that time, you’d get offered things on the street for sale. I was never offered a toaster but again, that's a heightened view. Boom boxes and stuff like that were always being sold because they’re always easy to flog. So, I was kind of like a slightly quirkier version of that. That was a fun shoot. That was crazy, though, because we were right on the drag of the Cross and we had a gangster walk ahead of us to tell everyone ‘everything’s alright’. He got paid a substantial amount of money from what I understand. So we were able to kind of continue with the shot unmolested. But, you needed that. If you didn't have that, you would absolutely get fucked. You were very motivated. ‘Let's get this done in a few takes.’

Then you get the final cut. What's the experience like for you watching the film for the first time and seeing what you’ve been working hard to achieve over all those years?

AO’C: You’re never just shown the final cut. You’ve got the assembly, the rough cut, the cut that doesn’t have the music yet, it doesn’t look great because it’s assembled roughly and it hasn’t been colour graded. At first you kind of look at it like, “Is this even really a film?” The first few times you see a film that you've written and shot, it can be quite confronting.

Then you see it at the cast and crew screening, or maybe the premier, and then you see it play in front of an audience, and you get to experience the film in a way that you hadn't before. I remember the premiere we had at Hoyts on George Street, and right as the lights went down, Johnathan, who is a dear friend of mine, leaned over and said, “this is all happening because one day, four years ago, you decided to sit down and write something and not stop.” Lights went off and the movie started. That was hugely gratifying and emotional, because I never really thought about it like that before.

I think experiencing it then with an audience was really a proper time to see it. Even at the cast and crew screening, they all knew what was happening. By seeing it at the premiere, you get to have the most objective experience possible. Seeing it again at the Inner West Film Fest, which was basically the screening that caused this re-release to happen. And we were like, ‘Oh, shit. This actually plays with an audience. This still works.’ So it was a bit like that. It was a bit like we were so close to it, we didn't know that it worked. And then it did, and that's an amazing thing.

It's huge. And then you go to Cannes as well.

AO’C: We did go to Cannes. That was crazy. If you are Australian in Cannes, you don't stay sober at all. I ran into some Australians on the plane, and then I drank and didn't stop until I got back to England, I was staying with some friends in England. It was just this kind of booze soaked roller coaster. I was 23 so I had no self-control at all. It was the opposite of self-control. So I have great, but also vague, memories of my time there. I watched a lot of films and drank a lot of booze and met a lot of great people. It was a crazy time. I’d travelled before, but I travelled with my parents. I’d never travelled because of something I did.

I met Lloyd Kaufman and talked his ear off for 20 minutes. He was very pleasant. I have no idea if he enjoyed the experience. I have some photos of me there next to Lloyd Kaufman. I got to see O Brother Where Art Thou right near the Coen’s. That was very exciting for me, because I love that film.

Let's talk about the theatrical release. It doesn't do huge numbers, but it finds a life on VHS. How did it feel seeing the film not track with an audience and then getting to see it find a life on VHS.

AO’C: I’ve gotta be honest, the cinema release was brutal. We had a lot of people in the know, in film business, who said ‘it’ll do this and this, and at a minimum it’ll do this.’ And it didn’t even get close to it. It was very sparsely attended. It came out at the same time as Scary Movie, which was going for the similar kind of audience. I think the niche that it speaks to saw it, but that niche across the country is tiny, and we needed everyone to come along, or at least more people to come along. That was brutal.

Don’t get me wrong. I was super grateful to have a film at the movies, and it was a wonderful feeling and all that kind of stuff. But having it underperform to that level it did wasn't great. It felt bad. You feel like you’ve done something wrong. It took me a lot of years to realise ‘you did your job. Your job was to write a script, and you wrote a script.’ You did what you could. But you have that kind of internalised sense of regret and kind of self-loathing and all that kind of stuff. I was a weird, pale goth kid anyway, so I had enough already.

It came out on VHS and we all expected a similar kind of response, and I don't think I still was in video shop at the time. I think I was pretty much writing full time then, but I still had a lot of friends and former flatmate and a bunch of people really close to me, the manager of a video store where I worked, and they were like, ‘it's never in. It's never on the shelf. People just keep renting it. It’s always out. People reserve it weeks ahead of time.’ So that's cool, you’ve got to order more copies in.

And then people were just stealing it. It’d been out for a while now, and people were just like, ‘oh, we're just gonna take it.’ They’d rent it over and over again and eventually people would just keep it. It was officially Australia's most stolen movie prior to internet piracy. Something like hundreds of copies just flew off the shelves. People just loved it and never returned it. They’d never pay the fines, so we had a lot of thieves who loved the film, so that was great.

So we were kind of thinking, ‘well, okay, now we’ll do a DVD release, maybe we can turn the story around a little’. Again, here I have to plead vagaries of time, it was either one of the distribution companies or two of the distribution companies or something, business was never my forte in this, they went bust, and all were amalgamated into something else, and, despite not using the rights for anything, they retained the rights for, I think ten years, it might have been five, but it was a period past which the momentum was completely lost. So it was a crash, and then it was like a rocket ship, and then a crash again.

Over the years we’ve revisited the concept of remastering and re-release it. We got asked about it a lot, like, any kind of event or sort of professional shindig, I’d have at least one or two people comment on it and ask ‘is it ever going to get a re-release?’ That eventually lead to Dov Kornits of FilmInk going, ‘hey, let’s bring it to the Inner West Film Fest, that's kind of the right crowd for it.’ We all thought ‘not many people will turn up’, and a lot of people turned up and they really liked it. That kind of lit a fire under us a little bit, Johnathon in particular, and we were like, ‘alright, let's see if we can make this happen.’ Then Screen Inc and Defiant got involved. And now here we are on launch day. It’s out on DVD and digital platform, and there will eventually be a Bluray.

The last thing I want to talk about is as much as the film is a wonderful artifact, the Angst website, angstthemovie.com, still exists and is accessible. It’s got all these great historical things on it, dildos for sale and more.

AO’C: So in 1999-2000 we started the website, and it wasn’t the normal film to have a website then. It was usually just here’s the poster and here’s the trailer. Jonathan in particular was really invested in having a lot of stuff there. So there's like articles, you could order the Grim Reaper bong or learn how to make a potato bong. It's just this fun little kind of time capsule. I think it's telling that Jonathan never shut it down. I think he probably always had the hope, as we all did, that one day maybe people would rediscover the film and I think rediscover the website. We talk about in some of the DVD extras. It used to be a more elaborate, there was a lot of flash animation. It's a little simplified now. There's still that little animation bits and whatnot. Yeah, look, it was just a funny little addition to the film sort of quirky world that some that we just thought it was just fun to interact with at the time in as much as anything actually was the time. I'm sure the people that stole copies of it well acquainted with the website.

It's got a real GeoCities vibe. I love it.

AO’C: I'm totally old enough to understand that reference.

I had more than a few GeoCities websites back in the day, and I'm glad they no longer exist, because I'm sure they'll be ended up on some list. There's a certain early internet vibe to it. I'm so glad that it still exists, because not only is the film itself this beautiful memory of what the time was like then, but having a website like this takes you right back to that period of the internet where that kind of stuff existed.

AO’C: It's funny too, because I just assumed the people into the film would be my age, or within 10 years either way. But at the Inner West screening, we had younger kids there, and they just loved it, ‘it's really about me.’ I think there are transferable and universal themes that they’re able to deal with. It's about belonging. It's about finding a place with your tribe and finding your people, which is evergreen. It's something that we never lose.

This has been lovely experience. Even if we only sell ten copies, it's been a lovely experience. I hope all ten are paid for, do not steal them people.

[1] The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 had its ban lifted in 2006. It was previously Refused Classification in Queensland, and is now available there. For a full history of film censorship in Australia, take a look at Simon Miraudo’s Book of the Banned.