How should we view our relationship with Artificial Intelligence (AI)? What if AI was like a child, and part of how we train AI algorithms relied on the basics of good parenting? This is the fundamental moral question at the centre of Aranya Sahay’s debut feature, Humans in the Loop.

Drawing from Karishma Mehrotra’s investigative journalism piece ‘Human Touch’ published back in 2022 and his own research while spending time in the Indigenous state of Jharkhand in India, Sahay knits a taut 75-minute screenplay that forces us to consider who really is the beneficiary of the AI revolution. And importantly, whose labour is this promised future predicated upon?

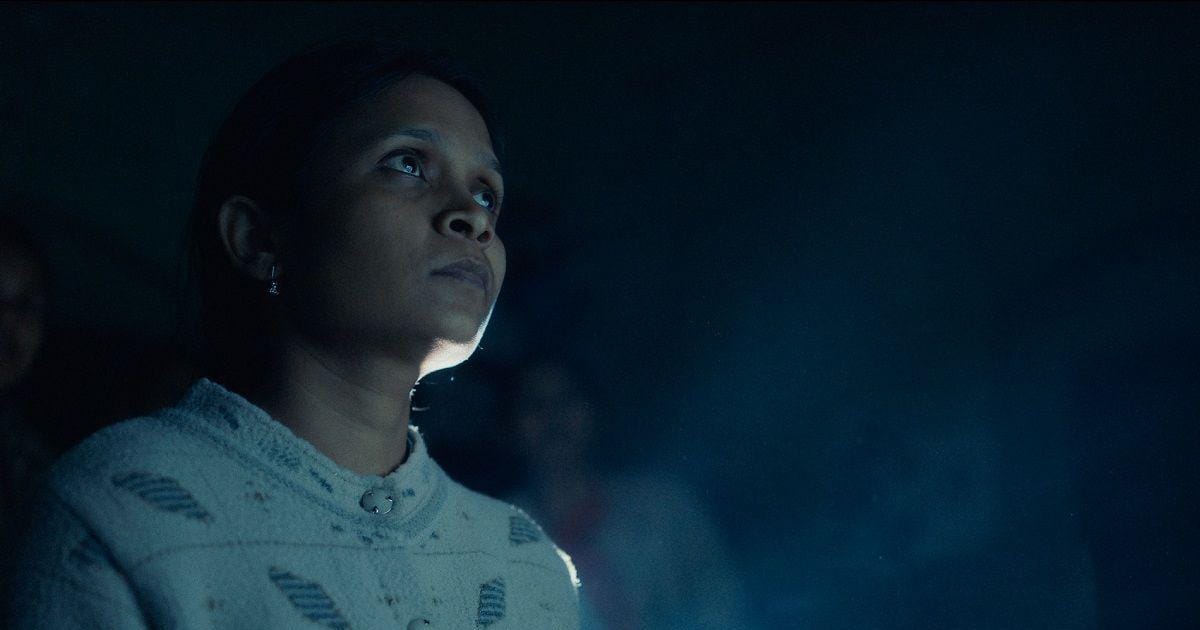

The film follows Nehma (Sonal Madhushankar), a single parent from a tribal background, who takes a job as an AI data labeller in Jharkhand. Her collectivist beliefs about nature and ecological systems come into conflict with the data she’s expected to feed into the AI algorithm, leading her to question her place in the world and her responsibility as a parent to her young daughter and toddler.

Sahay’s film arrives at a time when we are all grappling with the reality of how AI is changing the way we live, including the unavoidable environmental and workforce-related impact of this technology. The Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA) currently has an exhibition titled Data Dreams: Art & AI that invites audiences to reflect on the impact of the data economy on contemporary life.

In the middle of an awards season push, I caught up with Sahay for a deep dive about the film, including expanding on the ‘parent-child’ metaphor that holds the story together, the research that underpins the screenplay, the responsibility one carries when telling a story from another community, and why cinema shouldn’t always be oriented towards a conclusion.

Thank you so much for your time. I believe it’s about 10 pm in Los Angeles (LA) and you’re in the middle of an Academy Awards campaign for the Best Original Screenplay category. You’ve still managed to take out time to have a chat halfway around the world.

Aranya Sahay: Thank you for doing this halfway around the world and getting our film out there.

Let’s start with how this idea took shape. When we look at AI, most conversations in the Western world revolve around the economic impact; it’s all about jobs, it’s all about the environmental impact. But this is not that story. It’s a very different kind of story. Where did this story come from, and why tell this story?

AS: When I started to grapple with AI, I used to believe that algorithms learn on their own. Rarely have we found examples in sci-fi and science-oriented storytelling that focus on the backend of a technology like AI. When I read Karishma Mehrotra’s article, she spoke about Indigenous women working as data labellers. It was very, very interesting for me, because data labelling is the first step of machine learning. AI and machine learning are not just another technology; it's a tectonic shift. When I started to grapple with the subject of an Indigenous woman working with AI, I was thinking of approaching it in a slightly different way. Initially, I thought about deepfakes and content moderation.

I love screenwriting in that sense. It is a unique art form. It's not like prose writing. You inhabit a world, and then the world starts to dictate where you need to go. When I started to understand data labelling, I began to ask myself, what is it that these indigenous women are doing in these remote parts of the country? What has it got to do with AI? I realised that the job of repeatedly tagging a chair and a table to make an algorithm understand the difference is very much akin to parenting.

I was like, okay, if this job is like parenting, can AI be viewed as a child? That's when the whole thing opened up. If you view AI as a child, is it possible that AI is capable of only dystopia, or is it capable of the empathy of its ancestors, of the weaknesses and strengths of its ancestors? If I were not writing a screenplay, I would never have come this way. I would have perhaps gone into the content moderation zone, because violence is easy, right? Violence and pulp are easy things to do. But telling a civilisational story is not easy. The story itself: the milieu, Indigenous women, that space led me into this context.

AI systems are primarily first-world; they represent most of the Global North’s perspectives. This is evident in the way algorithms are designed. When an Indigenous woman works with these algorithms, does her perspective come into things? When I was in Jharkhand, the Indigenous state where this story is set, for close to a year, I realised that the place revealed the theme to me.

What happened in these Indigenous parts three hundred years ago was that settlers arrived from outside. They not only plundered these areas' resources but also disrupted the cultural fabric of these places. They left these Indigenous communities with a feeling that their cultures and their knowledge systems are lesser than the rest of the world. They left them with words like ‘savages’.

If AI was being trained primarily on first-world data, the same thing that happened almost 300 years ago could happen again. And that realisation only happened because I approached this material as a film and was physically in that Indigenous state. I read a lot of Robert McKee. He has said in his book [Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting] that when you entirely inhabit a space, when you entirely inhabit a milieu, the place begins to dictate the story to you. And that really happened to me.

Let's touch on the mix of secondary and primary research and how they come together. As you mentioned, Karishma's piece is the starting point that prompts you to go to Jharkhand and conduct your own primary research. The article ‘Human Touch’ also gives the film's title. Was that enough in there for you to be interested? How much of the story took shape once you were there in Jharkhand?

AS: Well, it's a very lucrative premise. There's so much to dive into just by the premise itself. But as they say, a great premise is a great curse. Because the film can get limited to being just a spotlight on this job happening, or this thing happening. It’s all about where you take this seed of an idea, narratively. What’s the end of it? Being in Jharkhand had a significant impact. I would be travelling every day, and I would see my protagonist in many of the women I met. I would see the divorce centres. I would see the way that place is structured. I would interact with many data labellers. The scene where my protagonist pushes back against a worm being labelled a pest because her paymasters are dictating to her is based on a woman I met at a data labelling centre. She was working on an agricultural module in which they were supposed to name a specific seed aligned with a particular season and crop cycle. Her manager said that you have to put it in a specific season. She pushed back, saying, ‘No ma'am, if you put it in this crop cycle, it'll not have the same impact as it would have otherwise.’ When I heard that, I was like, there is agency here.

I would have to trek a lot to find locations. And I would trek with Indigenous boys who were wearing Naruto anime t-shirts. One of them said, ‘Look at that tree? Can you see that worm there?’ I was like, ‘No, I can't see that worm, but tell me what your story is.’ So he started telling me that the worm on that tree is a specific kind that doesn't harm the tree. It doesn't hurt the plant. It protects the plant. And when these two points of research came in, they all of a sudden merged into an idea to include in the film—my protagonist being asked to label a worm that protects the plant as a pest.

Your protagonist is an amalgamation of several women that one finds in Karishma’s article, and also some of the stories that you've come across. When did you decide on the main through-line that you're going to follow? The film is not just about growing as a parent; it's about reclaiming your culture and understanding your own place in the world. It’s doing a lot in 75 minutes. When did you realise the film's main emotional beat?

AS: The realisation that data-labelling is like parenting, and then the exploration of AI as a child, it’s important to note that these are women doing these jobs, not men. If AI was like a child and my protagonist was the parent, that became the point of exploration. Who is this woman who begins to think that AI is her child? That really was the fundamental place where it started. In screenwriting, you tend to give your character a wound that sends them on a journey. What is Nehma’s wound? I kept thinking, and it took me some time to associate with it. What if she has a child who doesn't see things from her perspective? Then, her growing closer to AI as a child and believing in that idea would make sense.

Also, fundamentally, because she's an Indigenous woman, because she has tribal beliefs, that there is life in the inanimate, she believes AI could possess life. If this were a woman from any other background, she might not have even taken this idea seriously, that AI is like a child. She may have felt it was a euphemism. Arriving at the emotional wound opened up the story—why is it that she has an issue with her daughter? What is that issue? What happened in her life? It all starts with Nehma’s attraction and inclination towards AI. The fact that her daughter is half Indigenous, half city-oriented, all these themes, it's beautiful how they come together. I'm not just saying it because we're competing in this category, but screenwriting is the most beautiful art form to practice.

Towards the end, when she interacts with a particular animal, it reveals an unspoken connection between the daughter and her mother. And this brings everything full circle: the idea of AI, like a child, and this daughter, her own child, finally seeing through her perspective. This can only happen if you write a film. Films are like memories. The language of a good film can be that it'll jump from one space to another at one time, jump to another space at another time, and come back to the present, which is what happens in the film. Screenwriting can allow you to craft a visual language that’s like a fluid memory, a fluid dream. The idea that your parents reside within you, your ancestors reside within you, it all comes together for AI and for her daughter. You arrive at that theme gradually as you write. You don't arrive at it on the first day.

There's often a breakthrough moment that happens during screenplays, that ‘aha!’ moment when you finally crack the way you want to tell your story. At what point did you realise that this is what you want to say through your film?

AS: In the first two months of researching and writing, I cracked the fact that I wanted to do a mother-daughter story. But the moment I really felt I had the story was when a girl who's been raised in a city returns to her ancestral village. Her mother wakes up every day to take her to the forest to forage, and she’s not taking to this life at all. At some point, this girl will decide to leave. It's an easy writing sort of thing, right? When she decides to leave, she will get lost in the forest. That's also easy, because you want to give the idea of a ticking clock. You want to have some dramatic tension in that scene. But, you know what happened? That scene could have just been that. She would’ve got lost in the forest, and then she would’ve got out of the forest. And that also would have held some meaning for her, right? It can drive the story forward. But that’s not what happened. I meditate when I’m writing; I meditate with the images flowing through my mind. I was meditating, and I saw a quill pop up. I immediately knew this was a porcupine. I shut down my meditation. I immediately went to Google, and I searched for porcupines in Jharkhand. It turns out Jharkhand has the highest number of porcupines in the country, because it's an Indigenous state.

Virat, that's when I finally cracked the story. Like, now it's elevated. Now, the story is not just a story about AI. It's a story about connection—an intergenerational connection, you know? When that porcupine leads her out of the forest, and they develop a relationship, without knowing that the porcupine was her mother's friend, that was really the moment for me.

It's a moment that lets the film breathe. And it alludes to so many things. And, as I'm wearing David Lynch's t-shirt, if you try to analyse consciously, it just ruins it. There's a subconscious beauty to that image and that sort of resolution that feels complete.

AS: The intangible things don't reach a conclusion in life. You don't reach a conclusion for your trauma, for your well-being, you work with what you have. Why is cinema so oriented towards a conclusion? In that sense, the porcupine was a real breakthrough. How beautifully creativity works. I feel like something channels through you. Many creative people have spoken about that, that you're not writing something as much as channeling through you, and I have felt that as well.

Centering the story from a tribal perspective entails a particular responsibility for cultural sensitivity. What gave you confidence that you were the right person to tell this story? Obviously, the research was one part of it. But embedding yourself within the culture would have been equally important, and that would not have been easy.

AS: Of course, it's never easy if you're not from the community. I think these stories first belong to the community itself. I went from a very sociological and anthropological idea in the beginning, and then I understood the emotional plane of it. Filmmaker Emir Kusturica—who made a beautiful film called Time of the Gypsies (1988)—said in one of his interviews that if you don't belong to a community and you're making a film on them, try to align your own emotional logic with the logic of the community. And that's what I did. I mean, the whole mother-daughter story is actually a little bit of my own mom. I come from a broken family; my parents have not been together for a long time, and all of that seeps in, which is why it rings a lot more true, I think.

The one thing you can do sincerely is collaborate with filmmakers and artists from the region. We did that from the beginning. The first person I went to after a few days of research was Biju Toppo [Jharkhand-based anthropological award-winning filmmaker of tribal background], who later became my Executive Producer. We would speak for hours, and at every step of the screenplay and the edit, I would get his feedback on whether I was getting it right or wrong.

The promise of what AI can deliver to the First World is predicated on the invisible labour performed by much of the Third World. This in itself carries a colonial hangover. But the film's politics is a lot more subtle than that. How do we reckon with this complex truth that this invisible labour still goes a fair way in providing financial independence to a whole generation of women who would otherwise be stuck in less than ideal situations? It’s not your convenient white liberal feminist lens that you can lift and shift. How do we navigate this moral complexity in a post-capitalist society?

AS: We need to have an honest conversation about our privilege and also look at people who are less privileged. What does actual emancipation and empowerment mean for them? One of the fundamental things about the film is that it spotlights the invisible labour that is propelling AI, while the laurels of the AI revolution are awarded to the countries of the Global North. The backbone and foundation of this AI revolution are being laid by people who are entirely invisible in the media landscape and in any kind of conversation. And while on the outside it may look like a very exploitative world—these places where people are being paid one-tenth what they would be paid in the US—while all of that is true, these are places where the alternative to this work is to work in a field. And those systems are also exploitative, not just now, they've been exploitative for centuries.

If a woman can do this work and earn, say, 15,000 rupees in a remote Indian village while serving her family, it's really empowering. But it’s also really very embarrassing for the Global North. I've not tried to romanticise or demonise the invisible labour. We've tried to talk about a lot of other things, like our relationship with AI. What’s our relationship with nature, and where do we hang in that balance? I think that is more front and centre than the invisible labour conversation in the film.

Every film is a transformative journey in itself. And this is a film that is very much about being at the precipice of transformation. What did you discover about yourself by the end that you didn't know when you started the film?

AS: Wow, that's a great question. Well, this film is my child, it's my first child. I didn't know I had it in me to fight this hard to raise it and to find its own wings.

And now I know that maybe I had that in me, at least for my first film. I don't know about another. It’s been a long journey since our first screening. One hundred screenings, 35,000 people seeing it, and then Netflix getting interested because of the conversations that were happening. Then the grant [from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation], and then the theatrical here [in the United States]. This resilience is something that I didn't know I had. I thought I would have given up earlier.

Humans in the Loop was the joint winner of the FIPRESCI-India Grand Prix award, along with Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine as Light. It had its Australian Premiere at the Indian Film Festival of Melbourne. The film is currently available on Netflix.