The linking thread through the work of storyteller, filmmaker, and cultural historian Kalu Oji is the theme of connection to family, and by extension, a connection to culture. Both are linked to his notion of narratives being artifacts, historical documents that present the lives of characters existing in a time which could be now, then, or somewhere in the future.

This sense of timelessness is connected to the way Kalu Oji shoots his films with long time collaborator, cinematographer Gabriel Hutchings: namely, on film. Powerful shorts like Blackwood and What’s in a Name? act as a bedrock in their filmographies, giving way to the feature film Pasa Faho, a tender portrayal of a divorced dad, Azubuike (Okey Bakassi), who is trying to raise his son, Obinna (Tyson Palmer), while also navigating the difficult world of running a small business in a rapidly changing Melbourne. If families and culture connects these films together, then the warm texture of celluloid acts as the visual motif that makes up Oji’s body of work.

Shooting on film isn’t a nostalgic endeavour for Oji, it’s a creative and narrative choice which connects his films to the audience that’s viewing them, acting as an extension of the filmic experience and encouraging viewers to interact with the tangible nature of film. Watching Blackwood or Pasa Faho is akin to feeling like you’re in the presence of a living, breathing entity, something that exists out of a need to present an underrepresented culture on screen.

Kalu Oji’s films speak to the African-Australian experience, with the filmmaker centring Azubuike’s Igbo community in Pasa Faho. The title is a play on words – parts of a whole – and with that notion in mind, Oji walks us through the growing relationship between Azubuike and Obinna and they each find their own part of the community that they’re part of.

For Azubuike, there’s the expectation of success and stature that moves in conflict with the relationship he has with his brother, a priest at their church who has grand ideas about expanding the footprint for his congregation. Then there’s the cultural conflict that exists between Azubuike and Obinna, namely Obinna’s choice to use an Anglo name at school, amongst other aspects.

The other aspect that stands out from Kalu Oji’s filmography is the way he explores imperfect people. His characters are grounded individuals whose lives carry on off screen. In their hopes, dreams, and aspirations for themselves and their family, they make mistakes and fumble. There’s a considered presentation of humanity with Oji’s films that gives way to a kindness and supportive nature that elevates his characters, lifting them up in a way where you can almost hear Oji saying to them off camera ‘you’re doing your best, keep going.’

I’m deeply impressed by Oji’s work and was frustrated that it’s taken me this long to immerse myself in his worlds. Blackwood and What’s in a Name? are available online to view, and I urge you to watch them yourself, especially if you’re anticipating seeking out Pasa Faho as it makes its way around Australia with filmmaker Q&A sessions taking place. Check out the list below for dates in your area and visit the cinemas directly for tickets.

12 February – Mercury Cinemas, SA; 15 February – Cinematheque at GOMA, Qld; 21 February – Thornbury Picture House, Vic; 21 February – Brunswick Picture House, Vic; 19 February – ACMI, Vic; 23, 25, 26 February – Launceston Film Society, Tas; 25 February – Luna Leederville, WA; 28 February – National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, ACT

The following interview was recorded in early-February 2026 with Kalu Oji talking about the importance of shooting on film, how Deadly Prey Gallery factors into Pasa Faho’s life, and more.

This interview has been edited for clarity and conciseness purposes.

I’ve been immersing myself in your work ahead of this interview, and there's this beautiful vibe that you've built up over your filmography. This comes from your direction and writing, but it also comes from the way you shoot your films too. I’d love to start our conversation by talking about your choice to shoot on film and what that means for you in a narrative sense?

Kalu Oji: That's such a nice way to start the conversation. I'm glad that's something you picked up or you felt when watching the works. When I set out to make a film, whether it be at the short or a feature or any of these future projects, I [am] quite aware of the feeling I want the audience to have. What initially drew me to cinema and what keeps me coming back and keeps me falling in love with the practice is this idea, this feeling, of having this world open up to you, or stepping into this world [where] there are characters that you see reflections of, [and] that the ideas feel familiar and close enough to be in conversation with, but that the world feels very much like a world of its own.

I grew up watching films shot on film, and I've got such an attachment to that feeling, the magic of cinema, and what it evokes when I sit down and I see all that. I think that's what I'm trying to create in my own work. That's where that comes from.

To me, it captures this sense of warmth, but also a sense of history; what we’re seeing is happening now, but it also could be happening a decade ago. It speaks of the present and the past, and the importance of capturing these stories. The sense of history comes with shooting on film and the warmth and nature of the format. Migrant stories have been around for a long time, so it raises the question of why we haven't had more African-Australian stories on screen? It's a gift to have your voice out there and to be growing African-Australian stories on screen.

KO: I'm really glad that this comes across in the work, especially with Pasa Faho, it was very, very important for me. I've described the film a lot throughout the development process as it being this ‘artifact’. I wanted it to be an artifact.

It was shot in 2024. It was released in 2025. The characters have smartphones, and I guess that that maybe dates it a little bit, but beyond that, I wanted it to feel like the stories and the questions and the conflicts that the characters are grappling with aren't things that just pertain to the last two or three years. Like you said, they've been here for generations. We've been here for generations, and it's just now because of a whole number of reasons that we're sharing these stories on screen. I did want to honour that in a way.

For me, that looked like having a piece of work that was very present, but also could have taken place 20 years ago, that kind of captured that history, while still not kind of straddling the past too heavily.

Your two lead actors, Okey Bakassi and Tyson Palmer, gel together so well. Their relationship is one where they're discovering who they are as father and son, but there is also this sense that they've known each other for a long time. It’s a father and son relationship that's trying to figure out how it sits in their home, but also, from the father’s perspective, how it sits in Australia as someone with Nigerian heritage. They’re both great. Can you talk about building the characters with Okey and Tyson?

KO: That's a credit to both of them. The casting was so particular. It took a very long time to cast the film. Once we'd cast both of them, we were quite confident in what each of them could bring. Because we'd cast both of them online, you don't know what it's going to be like when they step in the room, but I think there's obviously so much of their own experiences and their own bodies that they were bringing to their roles.

We had a week of rehearsals. It was a very rushed week, but we did a lot; we hung out, we went to the arcade, we went and got food. We spent a lot of that time just getting to know each other. There's a kind of irony as well that Tyson is growing up in Australia, he's not Nigerian, he's a mixed-race kid growing up in this country, so he knows the parts of his identity that he can tap into quite easily.

For Okey, he has three children, and I think the youngest is a bit older than Tyson. As we were doing rehearsals that week before we were shooting the film, Okey was delivering lines and we were workshopping this material. Then a call comes in from Canada, where his family is, and I think his son was going through exams or something at that time, and he's like, ‘No, listen to your mother. You're not doing this.’ He put the phone down, ‘Sorry, guys, sorry, guys. Let's get back to it.’ That happened a lot throughout the rehearsal period.

There was a very solid understanding between the three of us of who these people were. And then thematically, within that rehearsal period and the online meetings we had beforehand, there was a lot of conversations about what we were trying to set out to achieve, thematically and tonally. It was a testament to them as actors, and the collaboration and the openness [they had with each other]; it was a really beautiful experience.

I read that you wanted to get Okey across a couple of weeks before you started shooting to acclimatise him to Australia and to recover from jet lag. What did you get him to do in those weeks before you were shooting?

KO: Man, in the end, we had one week. With Okey, it was quite a funny conversation. It's something that we reflect on humorously. He's a stand-up comedian veteran, and a Nollywood veteran. He's worked a lot in Nigeria, in the movie industry, and he's worked in London as well.

The way we were shooting is that we had five-weeks pre-production, five weeks production, and we had big, long edit. When we were having early discussions with Okey, I described this format to him, ‘Okey, everybody has to shoot for five weeks.’ The way I ideally wanted to work is that I would have had him over three months earlier. I love working like that and taking that time. I thought, because you're flying in from Lagos, maybe if you come two or three weeks earlier, it'd be fine. He said, ‘Ah, brother, wow. Two or three weeks? We don’t need to shoot for five weeks. Man, I'm reading the script. I can do it in one week. All we need is one week. Why are you stretching it out like this?’ I think our methodologies were quite different in that way.

He didn't come for a week. That's all we could get him for. But in that week, it was a lot of catching up on jet lag and a lot of discussions about the material. We rehearsed a bit. Even though we'd spoken about the film online and had all these meetings and talked about the material, once we were together in the same room, there were a lot of scenes we went through. I'd expressed what I wanted to communicate in the scene, and then both Tyson and Okey with their different toolkits would improv things or workshop things or present different ideas. A lot of those ideas made it into the final piece.

With Pasa Faho, alongside the family story, you centre the importance of third places that are outside home, places where community can commune and meet and catch up. Whether that's a church or a shopping area, it highlights the importance of these places away from home. Can you talk about the exploration of third places in the film and what that means, not just for the characters, but for continuing culture too?

KO: It's interesting to think about. It kind of exists at the heart of the conflict between the shoe store and the church. I don't think I have probably intellectualised it or sat down so intentionally and drafted it up. I think the idea was to capture the duality or the complexity of these places that somewhere like the shoe shop, which is this beautiful space that Azubuike has made his own and he's enjoyed many good years in and then it’s come to represents this place of stress, this place of shame or downfall.

There was a big conversation about the amount of energy [put into things], especially as someone who's in a position like Azubuike who is a migrant. You put so much energy into your business, into the shop, and your home is neglected. His home is kind of empty. He's sold his TV. It's a bit bare. I wanted to capture this contrast of how we kind of break up that attention.

And then, similarly, the duality of the church being this beautiful place where community comes to celebrate and to gather and to find support and safety and all these sorts of things. And at the same time, it can be this kind of vessel to oust your brother. There's this kind of capitalistic perspective to it too, you're at the disservice of your community. It's about trying to capture the greyness of these spaces.

I want to quote from your short Blackwood: “If I'm going to tell you how I feel, I want your full attention, so child, tell me, are you listening?” It’s such a beautiful line which feels applicable to all of your work. Your characters are speaking to one another, but then you're also speaking to the audience and saying ‘I'm telling you how I'm feeling, how I'm living, what I'm doing: pay attention. Recognise these lives exist.’ Can you talk about the importance of dialogue like that in a film like Blackwood, and how that sentiment lingers and carries on through your work in wanting the audience to pay attention to what you're doing?

KO: Oh, man, yeah, yeah, wow. I've come to describe the films I make as ‘quiet films.’ I don't think I'll make quiet films forever. I don't think the next one will be like that, necessarily. But I think something like Blackwood, even What’s in a Name? and Pasa Faho, they're these films that are quite domestic, they're quite tempered in many ways and I guess that's what I'm drawn to, tonally, and it’s the kind of work I've been wanting to see.

Beneath the surface of all these films, I'm trying to explore ideas and themes and questions that I feel are quite significant to me. They feel like life and death to me or to my existence, my understanding of self. This idea of wanting an audience to sit down and engage with something I guess speaks to that work but also speaks to how I see my career and see the films we make moving forward in a more general way.

You know, I always hope it's very intentional. And I always hope that even if people only engage with our films once every two years, and to come and sit in the cinema for an hour and a half, I hope that hour and a half is really, really intentional. Whether you hate it or like it or tear it apart or fall in love with it, whatever it is, I like seeing cinema as an active conversation between the viewer and the filmmakers.

Your main characters in both Blackwood and Pasa Faho are single parents. They’re divorced and trying to create the best life for their kids. Why is it so important to see those kinds of relationships on screen?

KO: I've come to reflect on this myself. It's just the characters I write because of the things I'm drawn to, and the spaces I grew up around. The parent archetype in that dynamic is someone who tries and tries and tries and tries and fails, and doesn't succeed in the end, but were able to pick themselves up and is able to be held into and to hold and to smile and to celebrate and to feel love and express love. I don't want to name names, but that's the people I grew up around and I think many of the archetypes I saw around me. I'm drawn to that type of character. So much so I don't think it's been a conscious thing to be a single parent, but it's just all the people in my mind's eye when I sit down to write these films, those kinds of characters. That's how it's been so far.

The way that you write not only the parents, but the kids too, is delivered with such compassion for the struggles or the successes that they experience. It's almost like you're breaking the concept of needing to have an antagonist and a protagonist. You can have dual protagonists, and you can empathise and can have compassion for both of them. Neither need to be an antagonist or a villain of the story.

KO: That's really cool. I love flawed characters. I love seeing imperfect experiences that are told with optimism or joy.

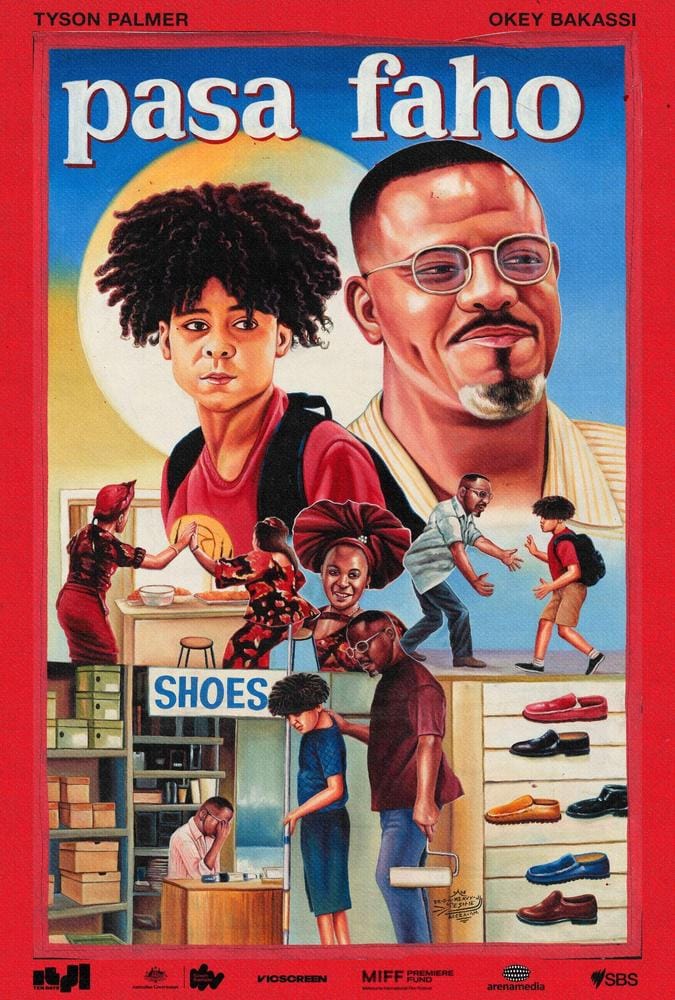

Finally, I want to talk about the poster for Pasa Faho. I love the Ghana style posters. Tell me about making sure that you had something that represented Africa in a poster.

KO: Throughout production we came across Deadly Prey Gallery's work. Not to sound like a broken record, but what we really, really wanted with this film was it to feel like this artifact, to feel like it's something handmade. When people watch it, it feels like you've spent the weekend at your Auntie's house, and you've gone into a wardrobe and you've pulled out this VHS, and it’s opened up this whole world to you. Whether you're familiar with it or not, [it was important] for it to feel tangible and tactile. That was down to every element of the film and of the process. The poster is the first impression people see when they’re introduced to the work. Everything felt right. It was West African. It was hand painted. It was handmade. We’ve got the big poster now here in Melbourne. I'm so, so happy with it.