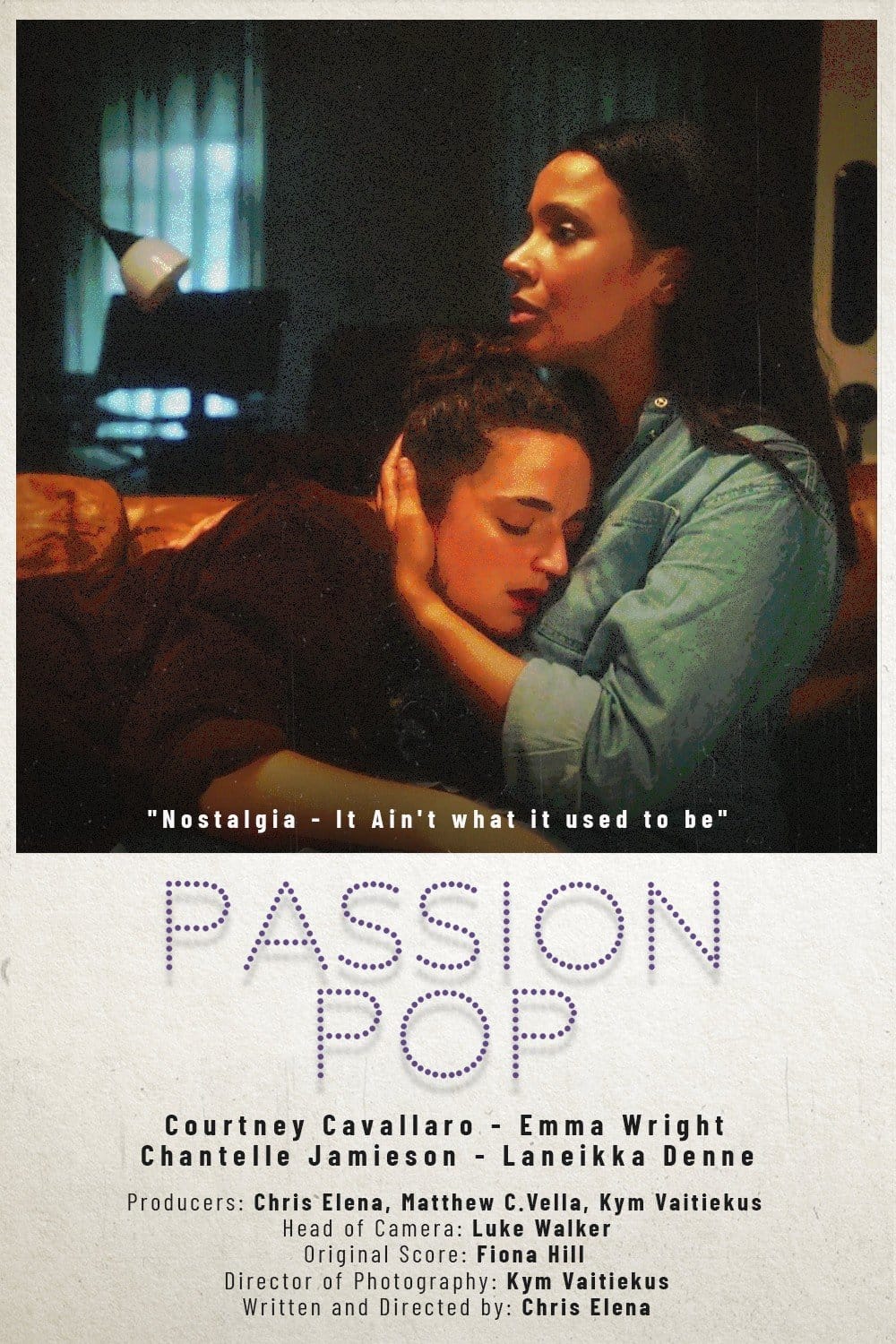

Fantastic Film Festival Australia is here once again and with it, a program blending strange and exciting new genre films with a slew of retro romps like never before. From Salt Along the Tongue’s mix of Suspira and 70’s Australiana to Hard Boiled (1992) and its freshly jazzed up score courtesy of The Rookies, it seems that this year has more than enough nostalgia to flood directly into our veins. And director Chris Elena, whose film, Passion Pop (2025), is showing as part of the Sydney lineup of shorts, feels right at home. A lover of genre, celluloid film and, unsurprisingly, Passion Pops, Elena’s filmography is eclectic, unpretentious yet insightful – often using the ridiculousness of his films to explore something far deeper.

Audio Guide (2020) turns existential when a gallery visitor not only discovers that her recorded guide has facts on everything in the gallery, but everyone; including every agonising detail of their deaths. Film Ratings become questionable in Refused Classification (2023), when a polyamorous couple are placed under the scrutiny of the Film Classifications Board. But Passion Pop (2025) doesn’t criticise our need to know everything or even condemn the bureaucrats deciding what love is acceptable to see. Ironically, it criticises nostalgia itself, as a clinically depressed woman is forced to go to her thirtieth birthday party while her family and friends try to help her forget her problems with a surprise blast to the past.

Chatting with Chris, Finn Dall asks all things nostalgia, film, and mental health, as the pair discuss the troubles with staying stuck in the past, the rise of appreciation for older films in online communities like Letterboxd, and the gems hidden amongst the festival program and abroad.

Passion Pop screens in the Sydney Shorts 2025 package, alongside other great local filmmakers like Darwin Schulze with Bluebird. For tickets and the rest of the line-up, visit FantasticFilmFestival.com.au.

Audio Guide (2020) and Refused Classification (2023) are fairly straightforward titles, but Passion Pop (2025) feels like the outlier. Where did the title Passion Pop come from?

Chris Elena: The drink Passion Pop is linked with nostalgia to [anyone of] a certain age. I'm very aware of that. I just heard the title for the drink and thought, “God, I wish there was a movie called Passion Pop.” I just love the name of the drink. Also, the fact that it was linked to nostalgia [was great]. Anytime I said Passion Pop, any Australian residents twenty-five or over – whether they were from Sydney or wherever – would just go, “Oh, I remember drinking Passion Pop.” And I'm like, “Okay, great. I've got this story about nostalgia that lines up. The film’s also quite melodramatic, so I thought having ‘Passion’ in the title just linked quite nicely.

Do you feel like Passion Pop fits thematically as well? Like the main character literally finds their passion ‘popping’?

CE: One thousand percent, yes! Because it's passion. It's literally got a punch, it's got something that happens, and it's kind of like the film's own narrative big bang. It really is just linking it with that feeling that nostalgia brings people of a certain age at a certain time.

I noticed similarly that your films often open differently. For example, Audio Guide and Passion Pop start with the credits and then end with the title sequence. Whereas something like Refused Classification has this whole intro themed after a red band trailer. Do you adapt your opening and credits based on the story you're building?

CE: Absolutely. I love films that start with their end credits at the beginning. I think the films The Forgiven (2023) and Vox Lux (2018) have it. When you do that, it brings attention to the narrative first and foremost, because you're doing something different, but [at the same time,] credits always have to be there. So, I think it throws the audience into the narrative [straight away]. [That’s why I] loved doing that for Audio Guide and Passion Pop, because when the story starts, there's a build up for both stories.

For Passion Pop especially, it's someone's anxiety and depression [that’s building]. We've got to get that out of the gate, or else the movie doesn't work. Audio Guide as well. We had to establish the device before you met the characters – and I could do that through credits. Refused though, you had to meet the characters first. You had to be thrown in and just know who they were and just be in the room with them. I knew people would have difficulty with the setup of their relationship.

Passion Pop’s title sequence made me think of Enter the Void (2009), Where you’ve got those colourful credits flashing by and telling you exactly what kind of film it’s going to be.

CE: Thank you, I love that film. But no, I do have a love for striking opening credits or something that makes you perk up. Might be me going, “Oh, my narrative is not strong enough, have some [flashy] credits,” but I just love it as an audience member, right? I know that I'm being taken care of [by a filmmaker] when I see good credits.

About the performances. You've got Emma Wright back from Audio Guide, you've got Courtney Cavallaro playing our main character; both have these quite emotionally vulnerable moments. Like when Courtney has to act out this rather confronting panic attack, and Emma meanwhile, is on the verge of tears for most of the runtime. As a director, how do you navigate vulnerable scenes, and how do you make sure your actors are looked after?

CE: There were two things that I did. I don't know if this is something I always plan for, but with any film I've made, but particularly this one, it's conversations that I have with the actors. I get them to know me and know that I'm quite emotionally open and vulnerable. “This is where this melodrama is coming from, and I want to ground it, because that's who I am. But I also want it to be yours.” I have conversations with them about who that character is, why they're having those emotions.

I don't usually do much in the way of rehearsals, but this one, I had to because it was so big emotionally. I also leave it open to the actor to change that character if need be. We’re discussing where they need to go, where they need to be. How comfortable do you feel? [The other thing is], because I had to go digital this time, [I could worry less about needing too many takes]. I love one to two takes when I know that the emotions are so high, because I don't want to put these actors through hell.

I try to make the loveliest, happiest, sweetest set imaginable. When I'm there, I'm trying to make everyone laugh and be really happy. My crew will often go, “Shut up! You're a nightmare because your shot lists are terrible.” But for the actors I just make it really warm and kind. I want them to feel welcomed and everything they're doing is not for naught.

That's a great answer, because obviously it's a lot to deal with as an actor, but also that you deal with as a director, navigating those difficult situations.

CE: One thing that was interesting was talking about movies with the actors, because they'd say things like, “Oh, should we be prepping the scene?” and I'm like, “I think you've got it, right… Anyways, What did you think of Todd Haynes' new film?”, and that gave the crew time to set up. So, it's just keeping it like we're all hanging out for a day. And it really just helped lift everybody’s spirits.

Nostalgia in the film is kind of seen as this way to placate your mental state instead of actually dealing with it. Courtney's character basically asks for help, she's very depressed, but her friends still try to push the party onto her. She says, “None of this was ever about me.” How do you feel about nostalgia?

CE: I think there are positives to nostalgia only if you're visiting it. If you're living in it, then it's a problem. Because then it becomes a mask, it becomes a band aid for your current state and your current issues, and then you're never propelling forward or growing emotionally. I still have friends who love listening to the same music. Love drinking those drinks at the time. They enjoy it, and they love it, but they keep it to that evening, and then the next day they go to work, keeping up with their responsibilities as a person.

It's kind of like forcing you to go back to this stage that you're not ready to move on, but you need to move on.

CE: Yes, yes. It's the thing of, you can't go forward if you're going back, right? And I think with these characters, and especially them trying to keep the party going, it really is that metaphor of when the party ends, the party ends. Nostalgia won't keep [the party] going, it's just you forcing something. Also, the friends are using it to save themselves, not Courtney’s character. So, there is an inherent sort of selfishness to nostalgia when you're trying really hard to grasp it, because it's about you going back and you're holding someone else back.

I didn't realise you were shooting on digital for this one. Once Courtney is hypnotised, there's this really interesting effect that you have that uses a wide-angle lens, and some weird noise and distortion. How did you go about working with your team to achieve that?

CE: I think it's a mix, because I did a big chunk of the editing (although I won’t take credit for it as the other editors came in and saved it). It really came down to the cinematographer and the colourist, because I explained to Kym, my cinematographer, that because we were shooting digitally, I was very afraid of it looking flat. Well, I wanted to really make the conscious choice of having the colour scheme increase, and the texture become more prevalent, as the film went on. So, it looks digital, but then has a little something else [on top]. I think when you're shooting digital, especially with iPhones and whatever 4K cameras Netflix are using, it looks [too modern]. When you're adding grain, texture and colour and back in, it's like the film itself is going back [in time with the characters] – back to celluloid.

Kym had done mostly film projects with you up until that point. Was it a difficult transition for you two going digital?

CE: No, if anything, it was easier. But it did make us miss film more. Because you can become complacent in your lighting and setups [with digital]. You can drop the ball on certain things and there's inconsistencies. With film, I'm very much dedicated to not having a monitor. If the framing is great and the focus pull is ready, we're going to get it in two takes, and everyone’s on the same level [with nailing those few takes]. With digital, we had a monitor so everyone could see everything. We could have seven or eight takes and less setups. So that was scaring me, but it helped this time, because we had a lot more pages to get through in a short amount of time.

What’s your opinion on modern film scans for major theatre releases and physical media? 4K Laser scans, oftentimes it will lose its colour or distributors will upscale or denoise Blu-ray remasters.

CE: I despise it. I can give you an example: Se7en (1995). That film is one of the most beautiful looking films out there. And I think the one of the big reasons that film is what it is is that noise and that dirt and that grit. And when I watched that remaster, there was a lot of noise gone, there were a lot of muted colours. I was taken aback. Why the hell would you do that? A lot of people say that stuff ages the film. And to me, no, it makes it timeless.

Lately, we don't really absorb vibrant colours in our cinematography anymore, everything is clean. So it dates the film [to the camera your shooting with]. Grit gives it character. They did it for The Warriors too, I believe. Now it looks too clean. Why the hell does it look clean? We're on the streets with some rough gangs!

You almost see an opposite shift in the indie landscape. I know Salt Along the Tongue, which is also part of Fantastic Fest, is shot on digital, but they keep the ISO high and the discolouration of the sensor to create more noise, not less. And with We're All Going to the World’s Fair (2021), Schoenbrun used Skype cameras and low-res cameras to create that kind of noise and high contrast colour. So, it's interesting that, even on digital front, there's this push for “less clean, less perfect”.

CE: It’s a step in the right direction because it gives that film its own look and feel. World’s Fair scared the shit out of me. Everyone was like, why? Because it has a feel to it. There is a feeling in that film where I'm like, “I don't like this. What the hell is this?” And I contribute that to the look of the film, or at least part of it.

Salt Along the Tongue, which also has Laneikka, one of our stars, I see that and I’m immediately grateful that it has its own voice. Making [horror] films less beautiful will often support the narrative. I think horror films look so clean at the moment. I'm like, “No, I want to see it [ugly]. I think with all of digital’s resources [at our disposal], we're not utilising it enough, like digital is easier to shoot. If you've got ways to make it look really unique, do it.

What in the Fantastic Fest program are you excited for?

CE: Fantastic Fest was kind of like my white whale of like, ‘God, I'd love to be in that festival.’ I’ve gone every year. I adore their programming. I'm going to try and see Sister Midnight, and Salt along the Tongue’s big on my list. A couple of the short films in the Sydney shorts program (I didn't look at the Melbourne ones because it was breaking my heart that I couldn't go). The Sydney ones sound incredible, I would recommend anyone to go to those. Summerland, I believe, is in the program, which is an Australian film that's been under-seen. I've had a lot of people say it's really got a great feeling and atmosphere.

What films inspired Passion Pop?

CE: In terms of inspiration, my all-time favourite is Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master. I told one of the actors, “Hey, can you watch this scene? It’s got a good hypnotism feel going.” We were watching it and she goes, “Okay, this is the movie you're making.” And I'm like, “What?” And they're like, “This is everything you're going for [with Passion Pop].” Whoops. So look, I'm probably just ripping off that, but I think The Master is just incredible.

Speaking of Schoenbrun, I Saw the TV Glow is incredible as well, and I think that should be seen more. I can recommend an [Aussie] film called BeDevil by artist Tracy Moffat, which is so underappreciated, But the minute I saw that, I'm like, “I'm gonna rip off this movie forever in the best way imaginable,” or just send love to it. It's the best Australian film ever made. That's a film that experiments with the form and aesthetics of Australian culture, especially highlighting the broad variants within that. It feels like no one’s seen it, and I'm like, “This is fucking nuts! Everyone should see this.” These are the types of movies we should be making here.

Putting that on my watchlist now.

CE: Please do. It blows my mind every time I watch it. It's a quasi-horror film, quasi-comedy. It's unlike anything you've ever seen.

On genre films, you've talked in the past about how part of the reason film school didn't really suit you, or a lot of filmmakers for that matter, was that there's a bit too much pretension in the film scene and a general distaste for genre films. Do you think with the Oscar nominations for films like The Substance, that genre films are becoming more acceptable in art house circles – especially as film lovers themselves are becoming more online through things like Letterboxd?

CE: I think so. A lot of filmmakers hate Letterboxd, but it’s where most people are discovering movies and watching movies, especially younger people, which is huge. For a while there, and I still think it's a thing, a lot of people who wanted to make films or art weren't watching films at all. They couldn’t be bothered. So that was scary, but Letterboxd created that space to go, “I haven't seen that. What's that? Let's go,” or, “Let's watch some classics.”

I think COVID also weirdly helped people watch more obscure films – and some older ones too. Obviously, not a lot of good things came out of COVID, but I do think people watched more, and I think they have a higher standard now. People want to see better films. Once they lost it in person, they had time to invest in sitting there and watching it like being at home and sharing that experience online. So, all this talk of, “Oh my god, films are in trouble. Cinemas are in trouble,” in a way they are, but I do think there's a higher standard coming out of it. Now, when we’re going [out to a film] we want better quality. We want to see older films and art house films. Retrospect screenings are selling out, whereas new releases aren't, and that's telling you something.

People are rewatching genre films and going, “No, these are great.” The Substance was given a chance because of things like Letterboxd, where they said, “No, it's great, and it's a genre film.” It's more of a shared experience. Genre films have become more communal. Films that are less regarded are getting all these re-evaluations because more people are coming out of the woodwork posting reviews online.

Mind if I ask what your Letterboxd Top Four Favourites are?

CE: Oh my God, I’ve wanted to be asked this my whole life. My four favourites: The Master. 35 Shots of Rum by Claire Denis. Southland Tales by Richard Kelly, which I'm trying to get the cultural train running on that one. I think unfortunately, with American politics mimicking the entire film, everyone's like, “Well, it's a documentary now.” And I'll go with a recent one. I shouldn't, but I will, Magic Mike XXL. I also think I had In the Cut by Jane Campion on there for a while.

It's funny that you bring up Southland Tales and wanting people to re-evaluate it, because I remember Zachary Ruane from Aunty Donna was promoting it for his Fun Time Film Club and said something like, “It's not a great film, but somewhere inside that bad film, is the best film ever made.”

CE: I think that’s the reason I adore it so much. It's messy, silly and all over the place. I saw it when it came out, and I just thought, “This is the best thing I've ever seen.” And everyone else was appalled by it. As a joke, I was convincing my friends that time would prove me right. But then I was like, I wish it didn't prove me right, because it was predicting some [horrifying] things. But yeah, no, I adore that film, and while I’m not serious about it, I wish I could do Southland Tales references and everything I've ever made.

With Passion Pop, is there anything that a viewer might miss on the first watch? Any Easter Eggs or unusual behind-the-scenes challenges that might be interesting for readers to hear about?

CE: The film has quite an abrupt ending, which is by design, because it initially started as a proof of concept that had a more fulfilling ending. But it was kind of counter to the narrative I was building. So I did have a lot of people go, “Oh, the ending is really abrupt. Where's the rest of the movie?” My only thing I say to that is, if you watch the film, knowing there’s no [neat ending], you start to notice the moral muddiness of [the film’s characters].

Spoilers, I guess, but I'll just say it anyway. But what [the friends] do to [Courtney’s character], the hard agree of, “Let's send her back, Let's hypnotise her, let's do it.” As an audience member, you might be along for the ride thinking, “That’s a great idea. Do it.” But when you look at it on paper, it's disgusting, like they're literally saying, “Let's make this person pretend she has no problem so we can deal with her.” It's literally people doing the worst thing ever [to their friend]. But they don’t feel that way in the moment. They think they're saving her when they’re ultimately making her worse to make themselves feel better. I want people to watch it from that moral stance, watch it thinking of their own moral compass when watching it, and seeing how they feel and how it ties into that ending.

Sort of like having a visual reading and a subtextual reading at the same time, so that then when you rewatch it, or you talk about it with friends, it becomes this “A-ha!” moment that leads into a tiny bit of discomfort about what we were supporting.

CE: Exactly! It's something I'm obsessed with that I wish I could – and am trying to do – more often.

I definitely see that. You've got that cool sort of tone, colour and music of a Soderberg heist film on the surface Yet the serious undertone. Similar to The Substance, actually, where Courtney is almost like the straight person in this absurdist world, yep. So you notice through her character that something's quiet wrong with this world she’s in.

CE: They're ultimately getting punished, even if it's a temporary fix, like Demi Moore in that film, kind of does nothing wrong, but she's given a chance that [thanks to Sue], never really was hers to begin with. It's raw.

I love when there’s a protagonist at the centre who is a victim to what's coming or and is trying to control [the fallout the best they can].

That's what makes good suspense and horror, really. That's what most people are scared of: not having control, being that person who's not in control of their own body, or their own thoughts.

CE: You get it. I appreciate that. Oh, someone did ask me if I was trying to make a horror film. And I guess I am.

Being inquisitive of the unknown is my best wanky way of putting it, where you get really curious about what the unknown is and is it scary? Is it wrong? What's it going to do to you? What control are you going to lose? So I'm very obsessed with that, I think, in a weird way.