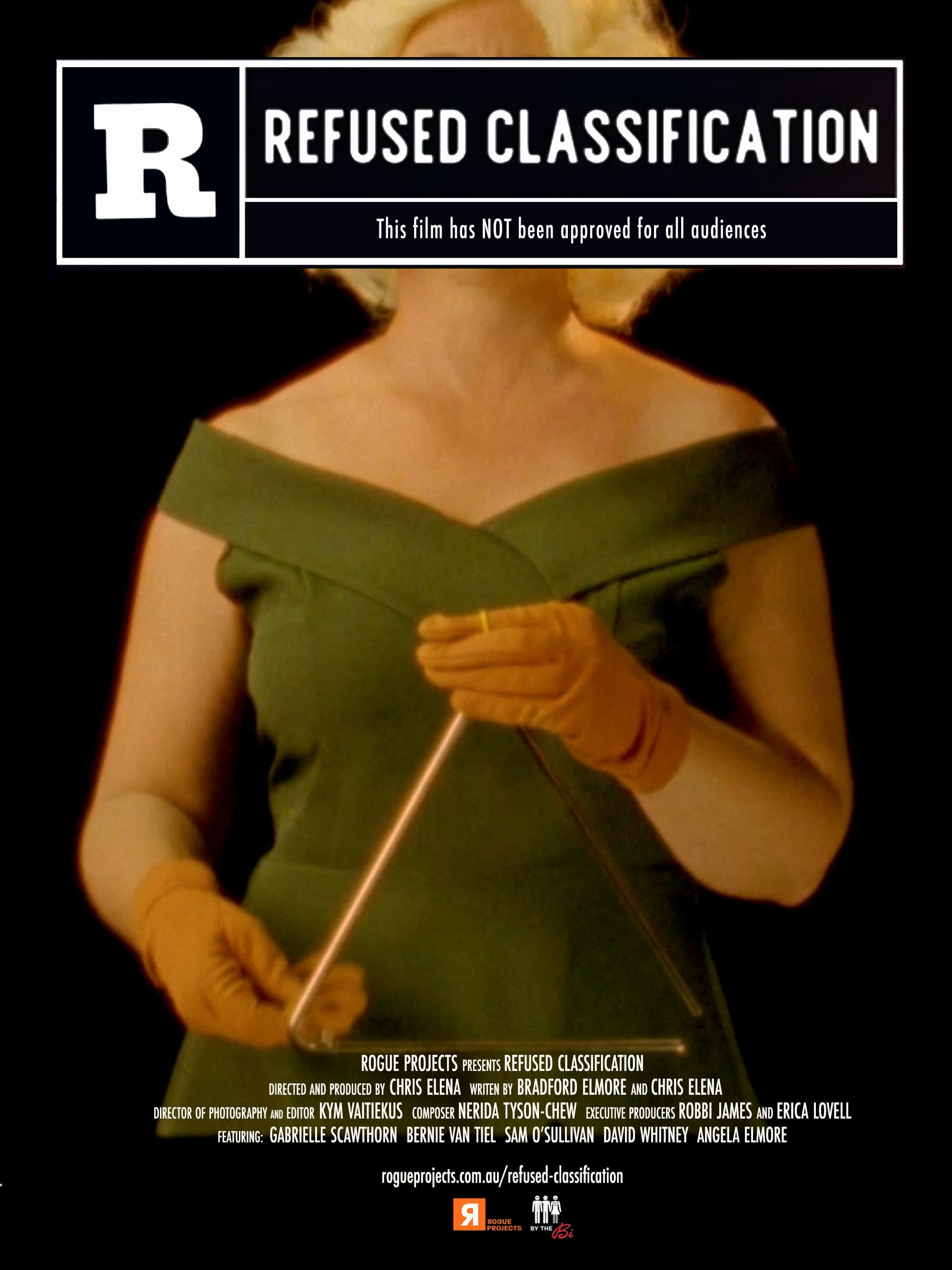

As far as indie filmmakers go, Chris Elena's philosophy melds past and present in both form and content. He shoots on Super 16 film for a certain look and texture, but his narratives are very much preoccupied with the particular nuances of queer expression here and now. His 2019 short film Audio Guide went a more Twilight Zone/X Files/Black Mirror (pick your era) direction as an exploration of mortality and faith, nabbing a Best Actress award for Emma Wright's lead performance at the 2019 Sci Fi Film Festival in Sydney, and scooping both Best Screenplay and Audience Award at the 2020 St Kilda Film Festival in Melbourne. Chris makes another festival appearance at Perth’s Revelation Film Festival with his latest short film, Refused Classification, a scathing hilarious satire of film censorship rules around the expression of queer love.

Nisha-Anne caught up with Chris over Zoom to talk with much enthusiasm and profanity about his filmmaking craft, the weird tension of sex and religion, his experience at film school, and how his first feature script is coming along.

Refused Classification screens alongside Raw! Uncut! Video! at Perth's Revelation Film Festival from July 7th through to 17th. Chris will also take part in the Short Film Panel alongside producer Kate Separovich and director David Vincent Smith on July 10th at 12pm.

First up, tell me how this love affair with 16mm film started.

Chris Elena: Okay, so I love the look of film so goddamned much that when I started making films around 2009-2010, that's when digital was coming in, and I was noticing that films were losing their colour. They were losing their texture. I was really like, "No, no, I don't want to do that, I want to go to film, I really love film."

There are a lot of naysayers about it, and people complaining about the process of it, “Where you're shooting something, you don't get as many takes, you can't watch it on the spot, you can't playback.” All of those things are like yeah, no, that's why I like film. I don't want to watch a scene just after I've shot it. Because either two things: one, everyone in the room is going to be watching that playback monitor and they're going to have opinions. And if they don't like what you're doing, there's going to be either a rift or they're going to not really have love for the project like you do.

It's not that I want a hierarchy, it's more of like I need everyone to trust me. That's one: I don't like playback, and I kind of like to watch it [way] after, give it a couple of days. The process of it I really like, and I like that you have to make a decision, and every decision you make when you're shooting on film has to be the correct decision, which I prefer. I like that idea of no, the decision I'm making is the right one and the one we have to do because we're here, we're doing it.

Whereas [with] digital, there's too much faffing about, and it doesn't look as good at all. The thing with digital is you don't have as much colour, you don't have as much texture, and you have to do all this work in post-production. A lot of digital films look like now, whereas if I'm making something, I don't want you to know when we shot it. I don't want you to know when the film is set. I want it to be watched in twenty years' time and [people] go, "When the hell was this made?" Given IMDb is not right next to them. I want everything that I make to feel timeless.

Specifically Super 16 is my ultimate favourite because that's the one [format] digital can't seem to mimic. It's been mimicking the look of film, and a lot of the times it's done an okay job with a lot of editing and post-production.

Like Knives Out.

CE: Yes, exactly that. Knives Out, that's got [the look of] 35mm and I was like "Oh oh!" But yeah, exactly that. Super 16 is the hardest one because Super 16 has more noise, more grain. And it's almost as if every image that you shoot on Super 16 is oversaturated which is my kind of look, I love it. So 35mm is 90s, early 2000s [is] 80s, whereas 16 is 70s. So that's why I'm like, "I want that, I want that feeling."

Doesn't that put a lot of pressure on you as a filmmaker in the moment to get it right?

CE: Well, it doesn't feel that way when we're shooting. Which is weird, because I think the thing is when you've got actors and a crew who are just with you and everyone in the room is on the same level, I feel comfortable. I don't like this thing of hierarchies. I think that's the worst thing for a film set. With film, it's the opposite. It's more like nope, we're getting it right. We're doing it, we're shooting.

Even with this one, there were some slight focus issues, which again we've remedied and fixed, and we always said if worst comes to worst, we can go back and shoot it. Also the thing with film is you're always on time which is outweighing any worries you have in terms of production issues with film. You're only doing three to four takes max. Whereas with digital, you're doing seven to eight and you're running more time.

When you're working in 16mm, it's mostly in camera but then you know that you can tweak some stuff in post if you want to. I know you did a bit of that with Audio Guide where you punched up the colours in the last bit to make her mood more intense. Are you ever tempted to colour-correct in other aspects, like the warmth and the vibrance?

CE: Yeah, of course, you always have to colour-correct with everything. With Audio Guide, we did a thing where as the film progresses, the colours get warmer. So literally the colour thing goes [on a sharp zoom up] up until the last scene in the bathroom.

With Refused, it was just a general colour-correction because there's a lot of colour in frame anyway, more so than Audio Guide. But the last scene I ramped up the colours so when she's giving her speech, the colours go up, up, up until it's the three of them and then it's just a blow-out of colour.

That's the thing with Super 16. When you blow up the colour, you really blow up the colour, and I don't think digital can do that. When you're doing colour-correction on digital, you really have to introduce that colour back into the frame and you have to work ten times as hard. The colour-grade on Audio Guide took three and a half hours. The guy who did it said this with digital would take two days.

Claire Denis said it: digital pushes colour away, film embraces it.

So 2009 you were making films. I'm going to show my ignorance of your age here, Chris. Was that after uni? End of uni?

CE: No, no, no. So 2009 I graduated from high school. So at the start of 2010, I had a choice: go to film school — mind you, HECS was not kind for film school, it was really more like HECS was [for] uni. So if I'm going to do film, I'm going to have to find a way to pay for it and it's going to be rough. So the choice was film school or learning screenwriting through a creative writing course. And in doing so, I can learn also how books are written and how poetry is written and really get a feel of how stories are told. Maybe that's the more beneficial one. So it was between the two.

This is the film school story. [Note: Chris had promised to tell me this story several months ago on Twitter.] I was like, "All right, let me do an introduction day at a film school. Let me try that one." Because I'd had early acceptance at [University of] Wollongong [for writing]."

I went for a day. And it was one of the worst days in history and I'm like, "All right, it's a sign." When I got there, there was a kid with a Where's Wally scarf, looking very dapper and very nice. And he goes, "Oh my parents are paying for this one. But the next one, the next course is on me." And I'm like, "I'm doomed." I'm wearing a ripped Iron Maiden t-shirt with red Converse and I'm like, "Oh."

And then we get into the classroom and the lecturer comes in, doesn't say hello, he's got a very obnoxious smirk on his face. And he goes, "Tell me the one movie that taught you how films are made and how films operate." And that's it, not even a hello. I'm like, "Oh this is warm." Lot of answers for Godfather, Seven, Fight Club, and I was like, "Okay." I'm not knocking the answers, it's just that they were the same five films.

I have a choice of two movies, but I went with a more generic one. I said Smokin' Aces which is an action film from 2007. And I got really aggressive looks, they were really like, "What? Smokin' Aces?" And then Where's Wally McGee gets up and goes, "Go on, explain that one." And I said, "Okay, it's a generic action film that taught me about blocking, colour-grading, how a scene works when there's spectacle involved." So it really gave me a better idea of how the camera operates when there's movement away from just two people in a room, talking, and it's a generic action film but that's the point. It brought me there. I love the film, but like it goes a bit more above and beyond.

And one of the cinematographers on it, [Mauro Fiore], he did Avatar. He's one of the best cinematographers and they got him just for this movie. The colour-grade on it looks like a painting. I was like, "That film really kind of blew my mind because I went to see an action film and I came out almost knowing how to shoot an action scene, knowing how to shoot spectacle in one sitting." That's why, I'm giving you a real answer. Mind you, the second answer which will tie in to Refused was Shortbus but no one in that room has seen Shortbus so.

And then the lecturer at the front was going, "No, you can do better than a Tarantino rip-off" and I'm like, "Okay, you're snobs." It was a snob test. And I said, "Okay, Crank 2. What a tour de force of cinema." And their jaws dropped. Then they said, "All right, what's your intention?" I said, "Well, I want to make movies. I want to shoot on film." They said, "Nah, film's dead. Film's on the way out, we're going digital." I'm like, "I'm out." Picked up my stuff and left. So I was only there for a couple of hours.

Love it. Man, I applaud you for going your own way. Now that I've watched all four films and in chronological progression, you obviously have a commitment to putting queer stories on screen. Is that a kind of mandate for you?

CE: Yes. There'll be times where if it's not in there, I'll find a way. I think now it's more prevalent, but growing up, it was not. And I was just like, "You know, if you put a queer relationship in this film or you had a same-sex couple instead of just a man and a woman, and you give them the same time you're giving to the centre couple, this film is far more interesting. It'd be so much more revolutionary." All you have to do is change the gender of one character. I always wanted to see that.

I was going to Dendy Newtown to get my movie content and I was seeing all this amazing stuff. And I don't know if The Limited [his first film in 2015] gave it away but I went to a Catholic all-boys school and it was a disaster. It was horrible. Seeing 16, 17, 18-year-old boys terrified of seeing a same-sex couple on screen or seeing any queerness whatsoever was mortifying to them, unless it was titillating to them. I was like, "Fuck this." It stuck in my mind and it kind of instilled in my brain [that] anytime you make a film, keep at it, keep going.

Every time I was watching films, queer relationships always felt more real, more lived-in. I related to queer relationships on screen more than I did heterosexual ones. Refused is a big thing for that. When I was growing up, queer relationships — they enjoyed sex and there was a joy after having sex and they would sit in that bed and they would talk. Because the only time you saw queer relationships was in arthouse film, they had the time to sit and talk afterwards and just have a smile.

Sex looked great in queer films. They looked guilt-ridden in straight films when I was growing up. When straight couples were having sex, it was either titillating but it's a thriller and she could be a murderer and "Ooh, we shouldn't be doing this." I went "Why not? Sex is great." This is me being 13, 14 and having access to Foxtel. And I was just like, "No, queer relationships got it. Straight ones are terrified of sex."

And then it tied into boys at a Catholic school saying, "Ugh, queer relationships." The films they're watching, they're scared of sex, and they look terrified. This is what heterosexual relationships look like on screen. We need to have more queer relationships, because that's meant to be terrifying, but it's not, you're scared of sex. So that was my thing of "No, throw it in there. That's your thing." And it's always stuck with me ever since. And also I like the idea of if I put a queer relationship on screen, I get to talk to more queer actors and more queer creatives. I can talk with them and we can have an honesty.

You know, it's funny, you're talking about boys being terrified of seeing sex on screen. I wonder: how would you go making a film about porn?

CE: Yeah, that's a great question. Porn is a fascinating one. A lot of porn is misogynist, and the culture is misogynist. I don't know much about the gay porn culture, but straight porn and the guys who watch it — there's a real hatred of women, it's like "Yikes." But there are aspects you could look into and explore the fear of sex or the idea of when you're watching a piece that is strictly sex and you were terrified of it. Does it seem more safe to you? Does porn almost seem like science fiction to someone who's terrified of sex?

I follow a feminist pornographer on Twitter, Erika Lust, and she makes really, really great representative porn where it's all different types of bodies or different types of sexualities. She very much goes against the misogyny of porn.

CE: Anna Brownfield is also a feminist pornographer. She's incredible. Just recently I got into her stuff and the feminist porn she makes. The women in those films are 50 and 60. They're beautiful, it's that idea of an older woman enjoying sex. And I recommend the documentary Morgana. Have you seen that?

No.

CE: It's about a woman in her fifties who was in a relationship, who was married with kids. She was suicidal, she hated herself, and then she slept with a man, like a sex worker and then she had a new lust for life. She started getting into porn and travelling around the world, being in her own porn films, and she's 55. It's beautiful, it's a great film. I highly recommend it.

That's really interesting because, you know, there's that Australian movie just come out, How To Please A Woman. And also Good Luck To You Leo Grande, the one with Emma Thompson.

CE: And that's [Sophie Hyde], an Australian director. Director of Animals and 52 Tuesdays, which is a pretty good film.

I was raised Roman Catholic as well so I know exactly what you're talking about in terms of the shame and the titillation and there's a naked man stuck up on a cross. Is that hot or not hot? You know? (laughs)

CE: Yes! (laughs)

Am I supposed to feel bad about it? But you made him hot.

CE: It's not my fault. Absolutely. It's so funny when you grow up at a Catholic school or have religion surrounding you. My family is not very religious, they just wanted me to go to a nice school. It was all fascinating because I could look at it more from a distance and go, "Okay, this isn't working, what the system is." The kids who are really Catholic or going to school that's trying to be extremely Catholic, they're all terrified of sex. If they are turned on by something, it's a competition or a joke or they're like giggling and it's like you can't enjoy this. Why aren't you enjoying finding something arousing? What's wrong with that?

I've always had that from a distance, I'm not religious and I watched so many movies growing up. Shortbus was a big one where — and I recommend it highly — where it's literally about three people in New York having sex and being really happy and excited about it and just being in love. I saw that and went "This is the best. And if I went to school tomorrow and recommended it to those guys, I don't know what it will do to them. They'll never tell me the truth if they found it titillating or fun." But that idea of religion, titillation, and the idea of the bodies we're seeing on screen as well is a big one.

Watch Audio Guide here:

You know, something that's just occurred to me, Chris, and I love this about your films and the way you're talking about it, you're very sex-positive. So how does asexuality fit into that? Is that something that you would want to address at some point on the queer spectrum? What do you think?

CE: Yes, big time. I think I want to talk about it because I don't know enough about it. My biggest idea of queer relationships from screen was through sex, that sex is wonderful. Because growing up in a school or in the culture that we have, sex is scary and sex is dangerous. So I think it's getting through that, understanding that, and then going "All right, what about asexuality? Let's look into that. That's wonderful." So I'm definitely hoping to look into that, maybe in the next film. But I want to talk to more asexual people and get more of an idea.

And do your research.

CE: Exactly.

You've had Kym Vaitiekus as DOP and editor on all four films. Tell me what that process is like, working with him?

CE: When I was in my creative writing course, I had made two amateur movies, because I'm like, "Just hire a nothing cameras, you don't know how anything works. Get your friends, put something on screen. It has to be a disaster, you're not going to learn anything. You didn't go to film school so get to work." So I did two. And then came the third one, The Limited, where I was like, "I want to shoot film, I need to shoot film, I need to do it." And this was at a time, 2014, where film was really not happening at all. Christopher Nolan and Paul Thomas Anderson had not stormed the gates of Kodak yet, going "You need to make stuff."

So there were cameras literally collecting dust and Kodak [film] I had to get from New Zealand. One of the people I used to make movies with, a friend of mine [said] "Hey, I went to a lecture with this guy named Kym and he just lives nearby and I approached him saying 'I know someone who wants to make a movie on film and can I get him to talk to you?'"

Spoke to him, and we just hit it off. That was it, like a house on fire. He was most intrigued by the queer subtext in The Limited. I said to him, "I hope this movie isn't going to come across as homophobia." He said, "No, the opposite." He retired and then I semi got him out of retirement. I said, "Let's make movies together. We do the edits together. Like I'm not anti-opinions. Let's make it together and really mould it." He's my closest filmmaking person. We're very close friends anyway. But if it wasn't for him, I wouldn't be shooting on film. I wouldn't know how. I learnt the most from him. He's in his sixties, so he's a seasoned veteran. And we just talk movies. The running joke is we have such different tastes on films that when we agree on one, it must be good. (laughs)

What's one you agree on?

CE: We agree on the film Pride. We saw that together after we had shot The Limited. And we both loved that and Kym [went] "All right, this is our system. If we both like a film, it's good." Like Snowpiercer. He hated it. I love it to bits.

I'm with Kym on that one.

CE: Heathens!

Hate is a strong word but yeah.

CE: He loves The Lego Movie and I'm like "I'd rather step on a landmine." Pride was the big turning point. "All right, we're gonna join forces."

So you both love 16mm but do you both have a similar idea of pace? Or do you have different ideas of pace and editing that you have to kind of work out?

CE: Yeah, great question. Yes, I'm more slower paced. He's a little more "Let's get to the point." That was also a learning curve for me where it's like "Don't let the camera just sit there. You're not a seasoned filmmaker yet. Learn about telling information in a timely fashion." He would be like "Let's get to it sooner" and I'd be like "Let's take a little time" and we both came to a compromise in the edit, which I think has helped the pacing on all of those movies.

If I was going by my initial ideas, Audio Guide would probably be 25 minutes long and Kym's like, "No, no, let's get through and get through it." Also shooting on film, because he's the editor on set, he'll go "Nah, we can't do that shot that way, it's not going to line up properly and the pace is going to be off. Let's do this." And I've become better at it. Him being an editor and a cinematographer, he knows pace. Also the look and shot choices, like let's condense three shots into one so it gives you an idea of the surroundings. So you know where your environment is, where people are, and how they're operating. We've just got to find a way to do it where you don't notice the camera.

The pacing is really good in all of them. I'm pretty sensitive to that as well. And also because I just rewatched Hunt For The Wilderpeople and there's a lot of quick cutting in there which I hadn't noticed before. I get really excited by quick cutting.

CE: (laughs) Kym's the same. I'm a quick cutting guy as well except when I make movies.

You said in an interview that you turned down funding because they wanted you to make the protagonist in Audio Guide male rather than female, and you were like, "No, all my protagonists are going to be female." Why?

CE: Why are they going to be female? I think it's growing up where majority of the protagonist you're seeing were male. A lot of the films that had female protagonists weren't on screen unless it was Tomb Raider. And I think that again stuck in my craw.

I grew up with mostly women, I was surrounded by my mum, my aunt, my grandmother. Every time I'd watch a film and there's a female protagonist, there's more emotion on display. There's more dissection of feelings and thoughts, and there's more sensitivity on screen. I want that. And I still think lowkey we don't get enough female protagonists in bigger films or just films that are widely seen. I'd like to keep doing that.

I'm a person who speaks how I feel emotionally, and I'm very open myself and vulnerable, I'm a very sensitive person. When I'm talking with women, I always have more of a breakthrough with them. I always feel more comfortable around women and talking to women and growing up with women. That might be another reason why when I watch queer relationships, they're more emotionally available and open and more accepting of things. This masculine sort of nonsense, I don't respond to it.

Every time I think of [making] a movie, I think if a woman was front and centre, there'd be more emotion on display. There'd be more things discussed, there'd be smarter choices, thinking rationally and more emotional intelligence. I always get that with female protagonists. And yeah, I want to keep exploring that. I also just want to see more female protagonists.

Read about how Chris came up with the idea for Refused Classification and how he cast the film on page two of this interview.

Refused Classification screens alongside Raw! Uncut! Video! at Perth's Revelation Film Festival from July 7th through to 17th. Chris will also take part in the Short Film Panel alongside producer Kate Separovich and director David Vincent Smith on July 10th at 12pm.

How did you come up with the idea [for Refused Classification]?

CE: Firstly, when I was growing up, I could see the most violent film imaginable with an MA rating. But I couldn't go to the Dendy and see a queer film or a film with a lot of sex in it that was R. And when I would see those films, those films were nice and lovely and sweet. I don't understand that. Then I saw this documentary This Film Is Not Yet Rated, and there was a story in there that stuck with me, it's kind of haunted me for years.

The film Boys Don't Cry got an X — well, it got an NC 17 which is America's X rating or R-18. And the filmmakers said, "Why? Is it because of the violence?" And they said, "Well, mostly it's because of the scene where a woman's enjoying oral pleasure and she's having an orgasm and she's enjoying it." And then they cut to the scene and the scene is just Chloë Sevigny lying down, smiling and enjoying an orgasm. And they said, "That's what got us an NC-17." But the same week, they watched American Pie and it got an R and it wasn't a problem.

I watched that going, "What if that film was MA and American Pie was R and that was the film I could see with my friends? What would that do to a group of boys or any young person watching a film where a woman's enjoying an orgasm?" When I saw that, I was [wondering] what films have there been that we've readily seen or that even I've seen [that did that]? And I've done the Dendy and watched SBS. It wasn't there, it really wasn't a thing.

So I went "All right. I want to put that in a scenario where what if you put real life in front of a ratings board?" And also the idea of different cultures. What if you put Australian people in front of an American board? Because the American board is so strict. A few people said, "Why don't you do it as an Australian board?" Because every film we get that goes into theatres is American, and all the cuts that are made, all the choices that are made of having mostly heterosexual couples on screen not having much in the way of sex, not saying "fuck" in reference to sex, that's all in the movies we watch. It doesn't matter about our system. If [the film] gets a lesser [American] rating, the film has been censored worldwide so everyone's got the same mindset.

And I'm obsessed with films that juggle tones. Like I love them, because if you can pull it off and love these people -- a joke's always funnier if you love the people who are saying it. That's where it came from.

You talked earlier about how there's so much more colour in Refused Classification. And that's something I really noticed on this rewatch. Because the first time I watched it was the first time I'd seen any of your film, I just assumed that that colour thing was just par for the course. But now that I've seen all four, the colour palette is really different here and the production design is really different. Tell me about the idea behind the production design and that use of colour.

CE: So that goes to Jess Stirnemann who did our design. She goes, "Well, what do you want the film to look like?" I said "I want it 70s. That's roughly the idea." And she said, "Why?" and I said "Because it has to look like a film that would not have been released or had problems getting released. Or this couple would look really strange from that in that time. Or like a polyamorous relationship would look so odd in the 70s." It looked odd in the 90s, it looked odd ten years ago. Even now, I still haven't seen enough of it.

I said "I want it to look like you don't know where it's from. It has to look like it could be a time capsule or a look that you haven't seen before or in a while. And it also has to look like the ratings board haven't changed." It also [was the] idea of what would have happened if this breakthrough came in the 70s and we had more films with queer relationships on screen and we have more polyamorous relationships? The idea of what if the mould was broken in the 70s? It's that fantasy thing for me. I said that to her and she goes, "Okay, well, we need to have this, this, this." And I said, "Done, do it." And she goes "Really?" I was like, "Yep, here's 500 bucks, go for your life."

Is that all it was? It was only 500 bucks?

CE: I think it was even less with the painting of the walls, because that was shot in a theatre and we had moveable walls. The paint cost the most money, everything else was op shops and hiring from different places. And I was like, "Yeah, perfect."

Wow. What theatre?

CE: It was the 505 in Redfern. I was looking for a house and saw the 505 and [thought] "What if we could just try and find a way to dress it up? Let's pull a Red Rattler [the set of Chris' 2018 short film Can You Dig It?] and make our own makeshift [set]?" Got there, they had moveable walls and Jess is like, "This is it, we can move the walls, we can cheat the shots."

When she said "this, this, this", do you remember what were the things she said? Was it like the green wallpaper?

CE: Vibrant colours essentially, yellow and orange. Have things with patterns, a lot of 60s, 70s, 80s was patterns. Even the clothes they're wearing, like how do we make it colourful but not too daggy that you're going "What's that? Why are they wearing that?" It was more of blending in with a colourful surrounding so patterns, vibrant colours and textures on things that you don't see anymore like lampshades and textures on the couch.

Love it. And then there's the painting on the wall as well. There's a lot going on. I actually did think that exact thing of it's this young energetic polyamorous couple in an old world. But then I'm thinking, no, hold on, there was plenty of polyamorous stuff in the 70s. We just didn't see it on screen.

CE: Yeah. We didn't see it.

At what point did you decide on the race representation? You got two redhead white people and an Asian person in the middle. When did that come about?

CE: With the casting, I had no idea what I wanted in terms of who like actor-wise. I wanted to see a lot of actors. I wanted to see so many actresses, I really wanted to get it down pat. And then time became a factor. I had Pamela, the woman in the middle, older. I really wanted to cast an older woman for this. But the actors we saw — Bernice [Van Tiel] had this command of — she was a person where she would give a performance and then in the performance, she'd go "Nah, get fucked." And I'm like, "That's what I want, that command."

I am a person who responds to people who will say "No, fuck you, fuck this." Because a lot of characters don't do it. That's a thing you notice with characters without personality in films, they're not willing to just get up and say "Fuck you" to something or have that ferocity and that fire. Bernice had that.

It was a thing with the producers and myself [of] we have to have a spectrum of different nationalities or more diversity in that couple. It's definitely a thing that's happened now where it's not two white people in a relationship anymore. That's expanded which I'm really happy to see, and I've wanted to do that more. We did make it a mission to try and broaden the spectrum of actors that were auditioning with different nationalities and different ethnic backgrounds.

But the one thing we had to agree on was the older man had to be white. Because every time you look at the MPAA or any ratings board, it's an old white guy. He was meant to be based on Jack Valenti who [presided in 1966 over] the Motion Picture Association of America. And he was an old white guy.

But it really came down to who was auditioning, who could we get? Who could we see? When Bernice came in, there were a few actors that were in contention. I had my reluctance at first and went, "No, she's younger, I really wanted older." And then I saw her again. And I was like, "No, she's got it." It always is a conscious choice to try and have more ethnic diversity on screen. Of course, we have to.

Absolutely. I love the fact that she wasn't the person being invited into the relationship. She wasn't fetishised, she wasn't the outsider. She had strength and personality, and he always deferred to her which I love.

CE: Thank you. That was the intention in the writing. With the casting, the producers that I had [also insisted] Pamela needs to be the person of colour or someone with a diverse ethnic background, because it can't be -- the redhead, Gabrielle [Scawthorn] — no matter how you looked at it, [she] will be fetishised. So she couldn't be young and she couldn't be a person of colour, because it always is that with "exotic" characters, gross words like that. I don't want that. You have to look at the optics of that. That was a very conscious choice.

Tell me about the use of music.

CE: I'm very conscious of music. I'm very nervous about it. I think music is potentially the hardest thing about making a movie in terms of juggling tones and what your tone is and where the music is going to come in. I've learned in making movies that silence is your everything. That no music is your everything, but you want to use it. It's almost that you don't need music, but you want it because it feels more like a movie and you're more comfortable when there's music. It will inform your choices and your feelings.

So with the music I wanted, I went to a few composers, and they had great stuff. But this was a hard movie to score. Incredibly hard. I went to our composer Nerida Tyson-Chew who had worked on quite a few big Australian films. And she goes, "Okay, so how do you want to approach this? Because the movie without music works well, but it needs music." And I'm like, "Great. So I want it to be sincere." Sincerity.

She goes, "Okay, so you don't want plinky plunky?" And I'm like, "What's plinky plunky?" [hums notes] I hate it, I loathe it with a passion. And I said "No, I don't want that. I want their reactions and their responses to this essentially awful thing that's happening. I want the music to go with how they're feeling, not the movie to tell you this is a comedy." I wanted the music to inform you how they felt in that situation and how they were fighting against it.

And also the meta part of the film is that the music's on their side. The music comes in because it's for them. The music doesn't like the censor. That was my thing. So when she's giving her speech, the music comes in. The censor was using music as a weapon, he goes "Nope, no music, no score," but then the music takes over for them and we're for them.

So we had to think of how could we have that interruption of music and music being in the space like it was just part of the movie and you didn't even notice it.

I noticed the music when the attention was drawn to it and then when he said, "There was that swelling going on there, we don't like that swelling." And I was like, "That was lovely."

CE: Yeah, it's that idea of what's the censor going to look at. Are they going to look at three people in love? Or are they going to go "No, that music is making this romantic, get rid of it"? They're going to look at the things that remove an emotional response, because he's looking at it as an instruction video. And also the idea that the music at the end had to be romantic without it shouting at you that it's romantic. Because it's the idea that it's three queer people who are so excited to fuck and be happy and in love. This is a romance, first and foremost.

Now that you've got four films under your belt, what have you learned about yourself as a filmmaker?

I'll tell you one thing I was cocky about, because every filmmaker has something they're cocky about — and I don't think it's shooting on film. I think that's a good thing. (laughs) But I think the cocky thing for me was the movies I was watching were telling me "You don't need a plot, fuck plot. It's all character. It's all just characters and learning about character and learning about a person." I think making four movies, especially Audio Guide which I think was the one of the biggest learning curves — no, Dig It might have been — is story.

You need to really have a story that supports these characters. The characters can guide how the story is told, but you still really need a story. And you really need to tell that story well, and you need to kind of tell that story in a way that doesn't sacrifice characters. That's my big thing. Having story and knowing how the story is told and where those characters are in that story and how they're guiding it also informs pacing, shot choices, really just informs your movie. I really think that it makes a concise piece of work that will last longer and stand the test of time.

But even before you get to character, knowing what your story is and how you're going to tell it, and how is this movie going to be not just different, but how is it really going to flesh out ideas and give you something in 13 minutes that potentially a feature couldn't?

Also I learned what I like and don't like about storytelling. Short film storytelling in general, because I think people have a real thing against short films. And I understand why because I think a lot of short films are structured as sketches as opposed to stories, where it has to have a punch line, and it has to be funny. Or if it's serious, it has to have a big twist. And I'm like, "Just relax. Just calm down. Tell the story." It doesn't have to have the punch of a feature, it just has to feel like you're satisfied at 13 minutes and you now have something in your mind that you didn't have before.

Are you a believer in in the three-act structure? Or do you like to break out of it?

CE: I didn't used to be. Now I'm leaning towards it. Because I'm like, well, your movie is going to suffer pacing-wise and timing-wise if you fuck around with the three-act structure too much. Embracing the three-act structure taught me something as well which I think helped with pacing: the second act is the hardest. It's not the first or the third, it's the second because it's the dead air between your introduction and your conclusion. And it's like, well, what's happening there? That for me is where you flesh out character. So that taught me a lot.

I know when I'm watching a film, I can feel that moment where you leave the first act and you enter the second act. And it's always at that moment where I'm like, "Okay, is it going to lose me or is it going to reel me in deeper?" You know?

Absolutely. You can almost get away with having a bad ending or an unsatisfactory one — not that you want that, but it's your second act that's more important than your ending.

So Chris, you're of Greek background, right?

CE: I've got a few. My dad's South American. And my mum has also got Italian and Maltese. I've got a bunch of nationalities. But Greek Catholic is clearly the most prominent.

Would you be interested in making something about the Australian queer Greek experience?

CE: I'd love to, but I think Ana Kokkinos has beaten me to that quite well.

If you're talking about Head On, we can move on from Head On.

CE: (laughs) I like Head On.

I like Head On too but Head On is fucking brutal.

CE: Yeah, it's rough. Ana Kokkinos films are not happy. No, I think I would, I'd love to explore something.

You have so much cultural richness to draw on.

CE: It's weird to me that in my head, my first thought is I want to know about other cultures. It's kind of like in my head I've got the Greek one, I've had that. But then I'll come back to it and go, "No, I really should explore that and put that into a film."

I also think Greek and Italian Australians and Greek and Italian culture in general has a reputation of being loud and obnoxious. I don't agree with that despite my bias, but I've seen it first hand, relatives and friends being quite racist and saying racist things in order to fit in or even look and feel more "Australian". Mostly older generation to be honest — not all of course. And these are people who I deep down believe don't really believe the gross things they're saying. Even in the moment I see it as them trying to fit in and not be associated with that loud and obnoxious reputation. It all feels very performative. I'd love to explore that in some way.

There's so much to explore in that in terms of like masculinity, even faux masculinity like that line in Can You Dig It? And also in terms of queerness for queer adults like us who grew up in a more fraught time. But now we have so much more expression allowed us than we were before, to be able to call ourselves queer as people of colour. How that ties into being Australian could be so fascinating. I like how I'm telling you what kind of film to make.

CE: No, no, no, I need it. This is great.

I feel like you could totally do that.

CE: I would shoot it on 16 still, so it looks like it's from the Australian 70s. (laughs) I'd love to do that. I'd love to do an Australian film set in the 70s. That's a big one. I agree. I love where you're coming from with that. I think we have the same sort of ideas. Again, when you're born with a different ethnic background in Australia, Australia is a weird place. Australia is an inherently very racist one. It's like what are we doing to fit in? That's like the first question. "How are you going to contribute to society?" I'm like "What are you talking about? I'm a human being, like I live. What do you want?" It's weird.

I am so fascinated by [the attitude that] in the 70s, no one cared about this stuff, like you called someone a wog and it was a joke. I'm like "I don't believe you. That's not true." I don't think the 70s was nice for anyone with a different background. I think it was nice for white Australian people and they would have a laugh at you. But that was still at your expense. This ideal thing that the 70s — everyone had a laugh. That's bullshit. You're lying.

What does it mean to be an Australian filmmaker to you? Do you consider yourself an Australian filmmaker?

CE: Yes. Absolutely.It means having a specific voice that no one else has because there's something so specific about Australian culture. And coming from here, like we were just talking about before, Australia ethnically and culturally is a very strange place. Our accent is strange, our colloquialisms are strange compared to America which we're so used to. I think being an Australian filmmaker is keeping a unique voice and keeping unique perspectives and kind of maintaining that strange air and that wonderful air as well as the problematic and odd stuff and not entirely make sense of it, but put it on screen so that culture carries over and the complexities of it.

So I think it's being specific because specificity is universal. (laughs)

(laughs) I love that.

CE: That's it. It's really hard to make a dull Australian film. Like it's happened but our culture is too strange. It's all quite odd when you think of it in the grand scheme of American films, even British films. There's a roughness to us as well.

Australian films aren't seen enough. I think The Babadook is incredibly specific compared to most horror films you see. There is a weirdness to that film that Americans latch onto and think it's this otherworldly thing. I think it's because it's an Australian film, the voice and the look of it.

So tell me what you're thinking for the feature.

CE: I want to make a feature about nostalgia, which is all the rage at the moment. But I want to make a strange film about nostalgia that juggles a lot of different tones, and has a touch of magical realism to it.

Ooh, that sounds very exciting.

CE: Thank you, thank you. It's extremely hard to write it at the moment because I have a lot more fun these days working on other people's scripts because that means as a director, I can go "Yes, I can do this, I can do that." Whereas with the script, I'm a lot harder on myself. I'm working on the plot now and working on the characters and just making it a cohesive whole. The last draft was 146 pages so I'm trying to cut that down.

Yeah, but remember when you tweeted about it and somebody said how Sullivan's Travels was 130? Because you know me, I love Preston Sturges. So I'm like, "Yes! Follow Preston Sturges!"

CE: (laughs) My man. No, but I know my sensibilities. If the script's 140 pages, the film will be 210 minutes. Because I'll throw things in and I'll just live in the moment.

Fair enough. Where are you thinking of setting it? Do you know that yet?

CE: Yes. Where I grew up, Kogarah, Bexley. I'd love to do some stuff in Bankstown and Liverpool.

Are you flipping between drama and comedy?

CE: It's more drama with a bunch of strange things happening in the middle of it that are kind of funny. I'm hoping to shoot the first half on digital and the second half on Super 16. It's more of a thing of going "I know I can't shoot this all on 16." So first off digital with like a decent colour palette.

That'll be super interesting, man. What was it like being accepted into Revelation Film Festival? Are you excited?

CE: I can't wait. It's a festival I've looked up to for a long time because they're punk rock. The film we're screening with is [Raw! Uncut! Video!] a documentary on gay porn in the 70s. I know! It's how they were shooting on video because they couldn't get support to shoot on film. And it's about the big revelation of gay porn and how it was kind of ushering the way into safe gay sex with AIDS and other sexual diseases. I'm like, "That's the movie you're pairing me with? Yes!" So I literally was like Virgin flights, done. My partner was like, "Do you love this festival?" I'm like "Shut up, we're going." That's a testament to what Perth is and what films they play.