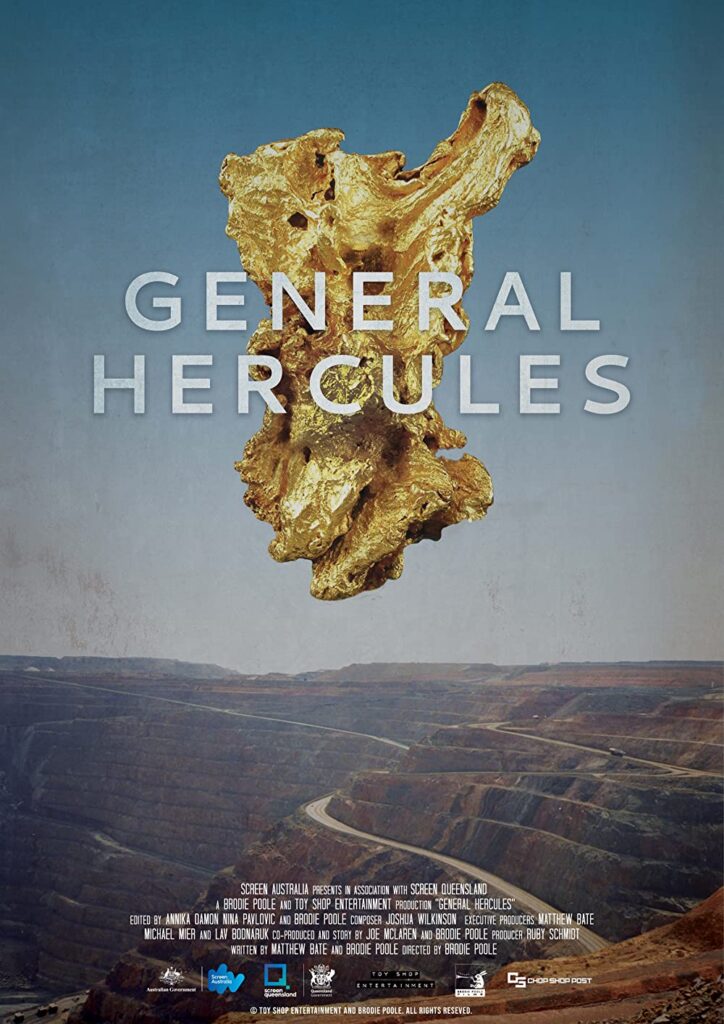

Brodie Poole’s explorative and politically-focused documentary General Hercules tells the story of the 2019 Kalgoorlie-Boulder mayoral elections, with the titular General Hercules himself (aka John Katahanas) running for the prime position of mayor. As we follow John and his fellow candidates’ journey, we get to see the wealth of land that they would help manage and maintain, including the all-consuming behemoth of a mine that is colloquially known as ‘The Super Pit’. With stunning imagery to back his narrative, Brodie has created one of the finest documentaries of 2022.

Part of what makes General Hercules such a riveting and powerful experience is the immersive and tone-setting score by Josh Wilkinson. In this interview, Josh talks about his musical influences, how he went about scoring the film in a large warehouse, and exploring Australiana through music while he lives afar in Iceland.

General Hercules will be screening at the upcoming Melbourne International Film Festival before heading online for MIFF Play. It also screens at the prestigious Cinefest Oz film festival in Western Australia.

For further insights into General Hercules, read Andrew’s interview with director Brodie Poole here, and then follow that up with Andrew’s review here.

I was really taken by General Hercules, I thought it was just a brilliant, brilliant film. What Brodie has managed to capture on screen is really fantastic, and then your score in particular just blew my mind and added so much depth to what was going on screen. So first of all, congratulations on creating something so visceral.

Josh Wilkinson: Wow, thanks so much. It’s so, so cool to get feedback. I also really enjoy the film. It’s so good to have a project that you just really love as a thing, not what you’ve done for it but just as a capturing of a moment. From the first few rushes I saw, [I thought] “Yep, this is exactly what I want to see on the screen.” When Brody first asked me, there was a bit of expectation that I put on myself, because I really wanted to elevate those images. And I just tried as hard as I could to do that.

When did you come on board?

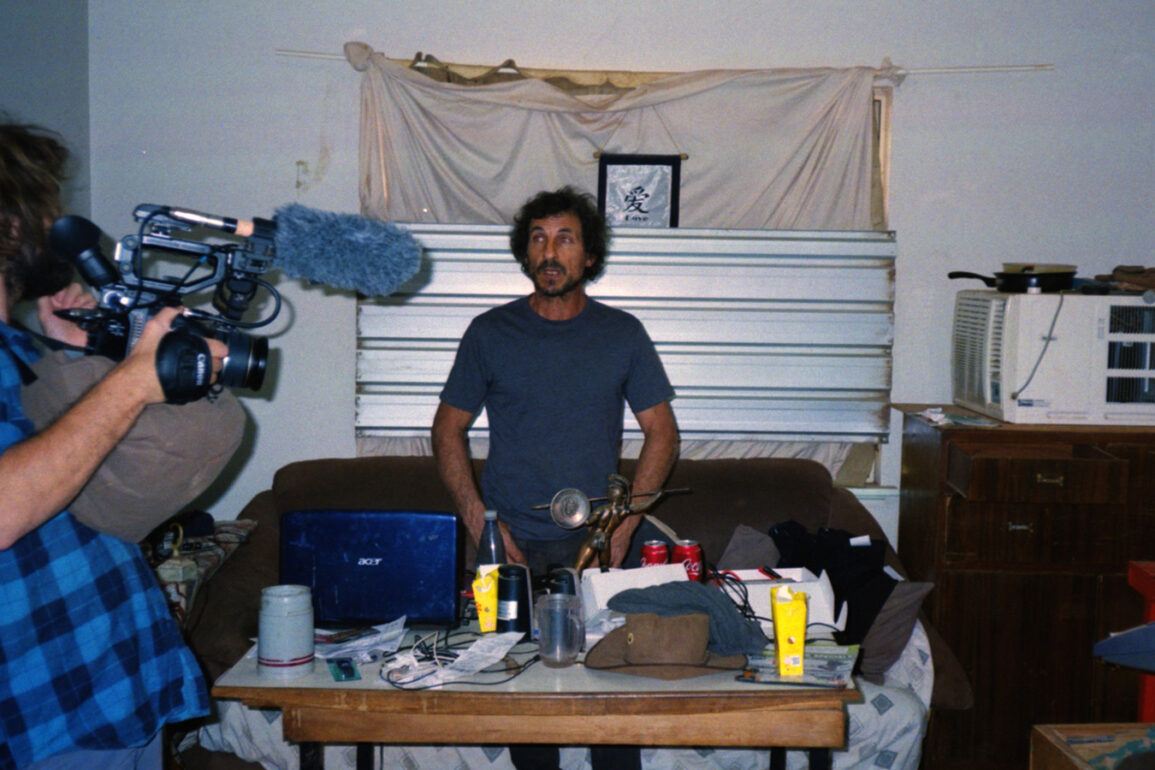

JW: Brodie had shot mostly everything. And then he was in Brisbane working at this amazing building that was kind of falling down, and he got me involved as they were starting to edit. So, we sort of did the edit process together. The process kind of went like this, I would go into this warehouse with three guys – Joseph Burgess, Nick Lavers and drummer Caleb College, and we would just put-up long rushes on the wall on a projector, 10-minute shots, and just kind of like play into the shots. And then we would give those really long jams to Brodie. And then he would stick them to things as he was editing. And then from there, they kind of got more and more refined.

Let’s talk about your influences, and then we’ll work back towards the score itself. The score feels like a little bit of The Dirty Three, but I’m curious what your influences are as an artist.

JW: Yeah, totally The Dirty Three. Joseph plays violin, we saw them at Vivid [Live] the year before and we’re big fans. And also, the classic Dead Man score [by Neil Young], Jim Jarmusch. The way that they did that, I mean, I was just completely copying that in the warehouse. I thought it was an interesting method because it allows you to really have a space for the sound. In a lot of scores and a lot of music that I like, the bands or the artists are recording something live in a space. A lot of bands I listen to, like a lot of the Nick Cave stuff, [in] those recordings you can hear the room, you can hear that it’s being played live, and that signature translates so well when you’re making a score, because everything has the same feeling no matter the mood you’re going for. If it’s all from the same space, then it feels coherent. I tried hard to capture it all there and do like very few overdubs and stuff.

Did Brodie give you any kind of pointers as to what emotion he wanted for the score?

JW: Yes, and no. It’s sort of obvious from the footage, very open, very empty, kinda like Australian Gothic. So, we didn’t have to talk so much about that, because it was kind of obvious. But there were a few scenes or moments that he wanted to capture, like some funny moments, some exaltational moments. Then we had themes. And when we threw up the shots on the wall, we would just kind of go “Okay, this one’s got to be more, happy.” Brodie was there a lot of the time, just sitting on the floor playing guitar, or like just kind of hanging out, but he really didn’t direct it too much. I think we were both sort of on the same page. I gave him so much material that it was kind of up to him. His role was more like choosing which ones went in.

The score resonates and it says Kalgoorlie so much. Have you been to Kalgoorlie?

JW: I’ve never been no. I was a bit sad. But I’ve been spending a lot of time in Moree [NSW]. I mean, it’s not the same, but it has a similar feeling in that town. I was sort of channeling that while I was doing it. My uncles are geologists in Perth, so I kind of know the vibe a little bit.

I was researching some great records that have been made at a studio, [Studio Asaph] in Boulder. They put out a compilation record of a few bands, like The Brownley Gospel Singers, an Indigenous gospel group. So at the very start I was kind of pushing to have a few tracks from bands in town, which didn’t work out. But I was listening to a lot of that music as well, trying to hear what people there were making.

One of the motifs that runs throughout the film is The Animals House Of The Rising Sun. Did that influence your choice of what kind of instruments you might be playing?

JW: Yeah, that one and the harp piece. The General [John Katahanas], obviously, he plays a lot of songs. And at the start, in the edit, there was a lot more of him playing. And we thought it would be fun to sort of meld his style of playing those tracks with the score versions and have them meld together. But then his versions fell away and then we were just left with the score version. I think the reason House Of The Rising Sun is in there is because he was playing it, and then I just kind of created a version in his style. But it did influence [the score]. I think it’s a great track, it sums up a lot of the vibe.

The whole guitar wailing, wailing violin, and like weird electronics, that really stems from the environment, like this pub rock noise that just seems to be seeping out of every building. And then the extremely weird sci-fi-like towers and mining equipment that’s everywhere. It’s very modern Gothic sci-fi in some ways, so I wanted to capture that as well.

It really felt otherworldly. It felt like this was just not a place on earth. And that score helped amplify that so much. What instruments did you choose to use?

JW: We had kind of two main studio setups. One was in the warehouse. I was playing electric guitar, and then we had Joseph playing violin, and my friend Nick playing electric, banjo and bass and Caleb on drums. We were just like turning it up really loud in those sessions. And then in my studio, we had more of a chill [vibe]. Acoustic guitars, banjos and acoustic violin. It was three or four main instruments. And then a lot of the electronicky weird stuff was Joseph [and I]. He runs his violin through like a big modular rig, and I was running through some pretty weird pedals. So we were getting all these like spacey sounds from that.

What kind of mindset are you in when you’re creating these? What’s the vibe in the room?

JW: The way I found this works is by asking people that you trust really well. Like Nick, he was my guitar teacher when I was in school. We’ve known each other for 15 years now. And [with] this kind of thing where you just throw up a picture and go for it, it doesn’t work with everyone, you have to really be in tune, and everyone has to really know what you’re going for.

So there’s two approaches. One is you sit there as a composer and you write all the notes out, and you make it all perfect, and then you get players to play it. And that takes a lot of time. But then there’s the other approach, which is very spontaneous, you just put people in a room and do it. But the time in that is building the musical communication and just the trust that you know what you’re doing.

So, there wasn’t much talking. Or much planning. It was just kind of like, doing it. The sounds help like when I was playing guitar, or when Joseph was playing violin, the words we were using were like, “Oh, this has to sound more rocky.” I don’t mean rock music, I mean it has to sound like rocks moving, or explosions of mines. Just trying to create soundscapes with the instrument, not like notes.

I understand that something you’re really interested in is exploring what sound can do [to people]. I’m curious for you, the [comparison] between music and sound, [is that they] are obviously very different. Music is music and sound is – as you’re saying –the sound of rocks and explosions and things like that. But I’m curious for you where the pull towards that emotional intensity that a sound can create comes from?

JW: I think it’s like, especially with film music, it’s just functional music. It’s completely tied to the story and the emotion that you’re trying to do. And so if you’re thinking about it like that, the gap between what is music and what is sound becomes very blurry because I mean, there’s some Kanye West tracks where he’s just using sounds to create emotions. But if you apply that same mentality to a film score, you can make just like a screaming sine wave just going like [imitates screaming noise], which no one would put in a song, but it creates the effect that you need in that moment in the scene.

So it’s always a good thing, I think, to broaden the parameters of what is sound and what is music. When I was in uni, studying this stuff, I loved the way that certain sounds just always created that emotion. You could just rely on it. So you can use that within music to do what needs to be done for the scene.

Where’s the difference for you in the [process of] creating something for a film, as opposed to for a song or for an in-person experience or an art exhibition or something like that? I imagine they each have got their own creative challenges that would arise. What do you find when you’re creating for those different areas?

JW: Film has a lot of built-in tropes, and the people who watch films actually understand a lot more than say, an art exhibition, where the rules are kind of loose. So in film, you can really play against the rules. Especially with this film, as I think you said in one article, the role of a documentary score is really just to make the pieces to camera not boring, it’s just to kind of move it along. And that’s all people are expecting. So when you when you go a bit further and make the score like a character in the documentary, people will respond to that. I like playing with the expectations. And that those are different depending on if it’s music, or if it’s an interactive installation, or whatever. But for music, you’ve got to tone it down a little bit, because genres are a thing.

Do you have a certain genre or style that you prefer to work in?

JW: I think with what I was just saying about my love of sound, I think that means that I don’t. I definitely like functional music and like playing with that, because then you can know what the audience is expecting and how you can play with it. But with my partner, I work a lot with her helping produce her music, that’s kind of indie, soft, electronic music.

I’m curious for you whether there is [an] intention to build a body of work? Is that in your mind as you’re creating each song or score, or is it kind of one project at a time.

JW: I’m definitely interested more and more in the projects that I say yes to. I’m not consciously thinking about creating a body of work, but I guess it’s happening. And the more I say no, and the more I say yes, it becomes apparent that it is very much about this Australiana-like identity. Pulling at the cracks of what that is.

I think as an Australian moving abroad, being in Iceland now for almost two years, it’s becoming more and more apparent what the Australian identity is as I have a bit of distance. And it’s super fun to explore that from a distance, because you’re not so caught up in it. And you can really pinpoint like when you see images from Kalgourlie, it’s so easy to be like, “Wow, this is so unique. And this is so amazing.” I really want to highlight that. So I’m saying yes to projects that go really to the core of the Australian issue.

How important is getting to pick apart the seams of Australian culture through music? That’s not something that [I imagine] many artists would be really keen on doing or know that they’re doing.

JW: One of the coolest things about this project was at the very start, as soon as Brodie told me about it, I just went and did a little bit of research about Kalgoorlie and Boulder, and came across this amazing paper, [A Social History of Music in Coolgardie, Kalgoorlie and Boulder 1892 to 1908 by Jean E Farrant BA MusB (Hons)] which was written in the 90s. And it was basically a collection of musical performances from Kalgoorlie-Boulder. From the beginning, it was like recording the first concert that ever happened in that area in like the 1890s, right through to the 20s. And when the first piano came, and what songs were played.

And it’s amazing, because it tells the story of what they were thinking at the time. The first song – which is actually in the film – that was ever sung in Kalgoorlie was The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo, which is a song about a guy who wins the casino in Monte Carlo, and then just walks out with all the money. So you can imagine what they were thinking at the time for that to be the first song ever performed. And there’s amazing accounts of [a] father and son playing violin and piano in the first sort of church, and the piano arriving. It’s incredible. So, exploring that and bringing that into a modern context and trying to sort of talk back to those early mentalities of the people is super what I’m interested in.

But to answer your question, when you come to a place like Iceland where the culture is so absent of any guilt, let’s just put it that way, you realise how much stuff there is being an artist in Australia. At least for me personally, it’s very difficult to do anything without any justification. Because there is so much that needs to be justified. So exploring how music or how any art can fit in with that and fit in with unpacking the story of colonialisation and what that means. And just having a small voice in that broader discussion is really interesting to me and important.

I’ve really enjoyed chatting with you about General Hercules. What collectively everybody has done here is just really brilliant. I’m excited for people to see it at MIFF as well. One of the films that is going to be screening at MIFF is Chopper, with Springtime and Mick Harvey doing a live score for it. I’m curious for you, [are] there any films that you would love to something like that with?

JW: There’s one film [called] Spirits of the Air, Gremlins of the Clouds. The imagery is amazing. I think [that] would be sweet to redo it. There is also a film from Iceland, it’s the first very first Icelandic epic Viking film called When the Raven Flies, and the score for that is period-like, 11th century Viking stuff, and then there’s like, DX7 and 80’s drum machines going [imitates drum machine] and they’re all riding on horses. That would be another one that I would like to do.