Filmmaker Michael Facey knows what it’s like to live as an artist in Australia. He knows the journey a film undergoes from the initial concept to honing the script to being on set bringing an emotional truth to life, and finally, to running the theatrical and streaming release gauntlet. Michael has worked as a producer on shorts and features, with the queer drama Sunflower seeing him journey across Australia with the entourage of filmmakers and actors in tow.

The WA based filmmaker is also a vocal advocate for the arts industry in Australia, using his platform to directly reach out to local and state MPs to question their stance on the governments role in supporting the artists in Australia. As Australia heads into another Federal election, one that sees Anthony Albanese’s Labor Party seeking a second term, Michael’s engagement and push for continued support for artists in Australia has increased.

Australian artists are naturally sceptical of the governments ability to advocate and support the arts given the continued level of disappointment that the wider arts community has experienced. This is a heightened realisation given the 2023 launch of the Australian Government’s National Cultural Policy: Revive: a place for every story, a story for every place[i]. The underpinning notion of this policy is ‘a five-year plan to revive the arts in Australia’. It’s a broad, optimistic piece of work that includes visionary ideas like embedding First Nations voices in cultural decisions, ensuring that all stories have a place to be told, centralising the work of the artist, ensuring that there is a strong cultural infrastructure in place, and ensuring that the audience is engaged.

Revive featured a request that the film and TV industry in Australia has been petitioning for throughout the years of the rise of streaming services has been local content quotas. Content quotas mean that streaming services such as Netflix, Disney+, Amazon Prime, and Max, would all be required to invest in local Australian film and television content, ensuring that revenue that would otherwise go offshore would be invested back into the Australian film industry that these companies often utilise or benefit from.

| Further reading: Labor promised local content quotas for digital platforms. So… where are they? - Crikey |

The arrival of content quotas was due to be in place by 1 July 2024, but at time of writing in April 2025, the implementation of quotas has not been actioned. The Australian Government has repeatedly stated that negotiations are underway, with Prime Minister Albanese stating on 3 April 2025 that[ii] ‘We strongly support local content in streaming services so Australian stories stay on Australian screens.’ Yet, with a Trump presidency in America and the impact of global tariffs, negotiating quotas within Australia has become a more difficult endeavour to undertake.

Quotas are just one part of Michael Facey’s advocacy as a filmmaker, with the producer also adhering to a level of transparency about the filmmaking process that aims to remove the notion that everyone with a film to their name is a multimillionaire with a private jet. While the ‘starving artist’ motif feels like a trope nowadays, the reality is that artists’ income from creative work averages out to be only $AU23,200 a year.[iii] Michael’s transparency about Australian filmmaker incomes in the below interview outlines the scope of unpaid or underpaid work that the industry operates with. While Michael’s story is just one in many that make up the Australian film and TV industry, it is symptomatic of an industry that is often under-supported and undervalued by consecutive Federal governments who have continually stripped away or diminished the work of artists that live within Australia. It’s important to note that for many artists in Australia, a sizeable amount of their annual income might be derived from government subsidies or grants, many of which need to be stretched out over years to accommodate the completion of their work.

https://www.instagram.com/p/DIQjE8CMgl-/?utm_source=ig_embed&ig_rid=10dccafa-3696-4495-87af-2dff3167ab50

It then comes as no surprise that many artists in Australia feel left behind by a government that on one hand says they’re advocating for their vocation, yet on the other hand, actively utilises tools of creative destruction for their own political progression. In the past week alone, we’ve seen politicians and candidates alike utilise generative AI to create soulless images of themselves as action figures[iv], with Albo's figure coming with a bonus dog figure, his cinematically named Toto, littering social media with cheap, trend-chasing images built on drought-inflicting software. We’ve seen both sides of the two-party political spectrum utilise AI-generated ads to bolster their political campaigns. Australian Labor have run TikTok reels featuring a dancing Peter Dutton and sappy Instagram posts featuring an accidental polydactyl cat getting medical treatment, replete with misspelled Medicare cards, while the Liberals have used AI to suggest that halving a petrol tax will invite aliens to Earth to take advantage of lower fuel costs (seriously) and that you’ll wake up with six toes on your feet under a Labor government[v].

The rapid rise of AI has left governments around the globe stumbling to catch up and implement policies or guardrails to safekeep information and creative industries alike. In 2024, industry and science minister Ed Husic proposed the concept of an artificial intelligence act that would regulate minimum standards on ‘high-risk AI across the whole economy[vi]’. As part of their 2025 election campaign, Peter Dutton’s Liberal Party has stated that it will ‘Support Australian businesses to lead in emerging scientific and engineering fields such as advanced manufacturing, medical research, artificial intelligence, blockchain, and space, turning innovation into high-paying jobs and global opportunities.’

It's then clear that neither major party in Australia has the security of Australian creatives in mind when it comes to the rise of AI. This became particularly evident after Meta used a pirated database of more than 7 million books and 81 million academic papers to train its AI model in January 2025. This is not an isolated case, with the works of authors having previously being used multiple times before to train generative AI models illegally and without their consent.[vii] That outright theft from Meta is something that Michael Facey has a direct connection to, with his Great Grandfather’s book, A Fortunate Life, being caught up in the swathe of Australian authors impacted by the act of stealing.

These aspects of pressure on the lives of creative Australians are what underpin the following conversation with Michael Facey. I caught up with him to discuss his entry into filmmaking, the role of politics in the arts, the costs of being a filmmaker in Australia right now, and how the cinematic experience is changing.

This interview has been edited for clarity purposes.

Introduction to Filmmaking: From The Omen to Working Class Stories

Where did your interest in filmmaking come from?

Michael Facey: My mum was always a film fan. I've got my love of genre and horror from her. She loved a good slasher film. She grew up in the 60s and 70s, so slasher films were coming into their own at that point. The stuff that scared her as a kid is the stuff that scared me as a kid. My dad hated horror, he absolutely hates blood or gore or scares, so I'd be watching these movies with my mum.

It became an obsession with movies and watching them over and over again. I’d go to the video store and rent the same movie out each week. It was always The Omen. I watched it over and over until I was banned from renting that film out ever again. Then you get another one and do the same thing until I wasn't allowed to watch that one anymore. In a way, it was studying. First you watch it for the enjoyment, then you're watching it to go, ‘Okay, where's the trick? How do they do that?’ Later on, behind the scenes stuff on DVD would tell you how they did it, but back then there was no such thing. There was no internet. You couldn't research things, so you had to just watch and try and look for the for the trick.

So, wanting to be involved in the making of movies came out of watching movies and asking, 'how do you make that?'

Where did your interest in telling Australian stories on screen come from?

MF: We don't see enough of our life on screen. We watch so many American films that you get such a feeling for American lifestyle and culture. You don't see our own Australian lives. A lot of it comes from wanting to see our own lives on the big screen. The stuff that happens to us every day, whether in the city or the country, put that on screen. It's fascinating. I know for the rest of the world, they’re curious as to how we live. They all think we ride kangaroos and we get attacked by koalas and all these sorts of wonderful stories that we might perpetuate when we travel abroad, but they want to see how it is. I want to work in genre as well, and Talk to Me and Wolf Creek were great for everybody, because it showed that wow, Australian genre can travel. There is an interest in it. We've been saying that for a long time, we just haven't had the chance to show it.

As a filmmaker, on a cultural level, what does it mean to get to see other people's stories from an Australian perspective?

MF: It gives people a voice. We always say it's the need to be seen and heard. A big problem we have in our country is that the little people don't get seen or heard. We get a lot of frustration with politics in that unless you have the big, powerful voice, or you're in a position of power, you are ignored. That is our life. Politicians don't ever want to listen to us, except for when it's election time, and even then, they don't even listen.

My local member is refusing to meet with me until after the election if they win. I'm like, congratulations, you haven't got my vote because if you won't meet with me when you're begging for the job, why would I want to meet with you after the fact? So, a lot of that frustration where we go, ‘we don't get to see ourselves, we don't hear ourselves,’ means that we feel that we're insignificant. We don't matter.

And that's wrong. We all matter. We're all significant, and we all have a right to be heard.

The notion of class is not really considered or discussed in a modern context in Australia. If you've got privilege or went to a private school, you can be a filmmaker. If you’re working class, you can't be a filmmaker.

MF: It’s so very true. In school, I wanted to be a filmmaker. I went to a public school and it was like, ‘well, you'll need a job as a backup. You’ve got to go do this. Go to university as a backup.’ No, this is what I want to be.

There’s a group of us and we coin ourselves ‘working class filmmakers’ because we come from working class backgrounds and we have working class lives. We didn't have the advantages of private school or financial backing and things like that. To make stuff, we've had to scrimp and save. It's not just go to Daddy, ‘can I borrow the credit card?’ We haven't had that luxury. We've had to figure things out.

I remember the first camera that I bought was. It was $1,000 and back then that was a lot of money. I saved for by 18 months to buy that $1,000 camera. Nowadays, kids don't blink an eye when they spend $6000 on the Black Magic in the full kit. But, you know, $1,000 for a camera; and it wasn't a great camera, it was like an analogue thing to shoot stuff on. We made a lot of short films and stuff. They weren't great films. They'll never, ever see the light of day. This was in Kalgoorlie. We’d sneak out at night and make little zombie movies, things like that. We weren't even 18 at the time, I wasn't even meant to be out of the house. I’m still afraid of my mother's wrath. They're not with us anymore, but I'm still afraid of her wrath.

We just went out and we had to learn, and we felt shocked. They were terrible films. In this day and age, you'd probably shoot them on your phone, put them on social media, and get likes and get attention that way, and but we didn't have that avenue back then.

That leads us to funding. How did you go about funding Sunflower?

MF: That was all private. That was rejected by every agency. The thing is, the agencies aren’t always going to take a chance on a first-time director. There was so much about it that is not tickable to fund through an agency. There's a lot of risk. There's not a lot of attachment. There's no marketability to it. It's a very personal story. It's very niche. So, for any funding agency, it's a high risk. There’s no distributor attached. There's no sales agents attached.

It's a story that had to be told in its rawest way. I think if it was given a budget and all those extras that come with being recognised as a funded film, it might not be the same. I think by being as dirty and raw and gritty as it was, it was real and true. Gabe was able to tell his story, and I think that might have been sanitised if it was done through traditional means. Once you have external pressures involved, with that comes a lot of notes and a lot of opinions. For some stories, you’ve just got to trust the filmmaker, ‘go tell your story, tell your truth.’ For Gabe, I don't want to speak for him, but I know a lot of it was therapy for him, because so much of what happened in that film happened to him or friends of his in real life. He needed that outlet.

To have somebody else in that space, tinkering with that would be difficult.

MF: Yes, it certainly would be. He had to get it out. If it was done through an agency, things become sanitised and safe, because then you run into the ‘don't bring us into disrepute’ clauses. Not that there was anything like that in Sunflower, but the caveats become attached. In WA you can't have an R rating. The most you can have is an MA rating, which is hilarious, because you don't get a rating until the after the film's finished, but you’re immediately being censored into what you can depict in your film. Some films can't work that way.

If you're doing it for a studio, the studio mandates ‘this must be PG-13.’ You go into that deal at the beginning. But for other films, it’s like, you wouldn't do an Evil Dead film with a PG-13 mandate. It will never happen. So, it all comes down to the deal.

I think something like for a film like Sunflower which was done in Melbourne, you're dealing with VicScreen. They're an agency with not a lot of resources and a whole lot of demand on them. We talk about how ScreenWest has a lot of demand and not enough resources, well, it's an even bigger scale in Victoria and it’s the same in New South Wales. So small films are harder to cut through the noise of the agencies. They want to go on safe bets and untested and unknown filmmakers are not a safe bet. That's just the reality of the funding model.

Australian Federal Election 2022

Let's jump back to 2022. Australia gets a new government, Albanese’s Labor government. Tony Burke is the returning Minister for the Arts. He hits the ground running with this great proposal: Revive: a place for every story, a story for every place. He does a tour around the nation, selling it to the artists of Australia. I went to the event at the Rosemount and listened to him from a pulpit, saying, ‘you've got our support. We're going to elevate you and make sure that you're looked after. Here is our new policy to put that in place.’

What were your feelings then?

MF: Oh, back then, I was ecstatic. I mean, I just remember being at SPA (Screen Producers Australia) one year and Burke did his great big speech there to all the attendees, and it was all about how he was going to back our industry. Prior to this, we had three terms of a Liberal National Government, under Abbott, Turnbull, and Morrison, with arts ministers who just did not give a damn. There wasn't even a Department of the Arts, it was part of the Department of Mines and Infrastructure. Paul Fletcher will probably go down in history as the worst arts Minister this country has ever seen.

We had a period of nine years where we were cut and demolished. I remember SPA saying, ‘we've got to be careful how we approach this government because right now subsidy is a dirty word.’ That's when the car manufacturing industry in Australia was dismantled because the government refused to bail out or subsidise things. You couldn't even use the word subsidy or anything like that, because you didn't want to face those cuts. So, we had a hostile Liberal government for nine years.

Then Burke was a breath of fresh air. Wow, someone that gets it. In the 2010s he was very passionate for our industry. There was a huge period of change back then too. We were excited. We were ecstatic. We're like, ‘finally, this is the thing that we've held on for so long for.’ We've gone through hell with the Liberals, and here we go, these guys get it. We've got to do everything in our power to get them in. And then when they get in, it's like, great, we've got to support them. They're here to look after our industry. We now have a chance, you know? We can now compete. We will now be able to see our work on Australian screens.

Before this, the Liberals abolished the free to air quotas. All of a sudden Australian film and TV content had dropped 60% or something. Kids TV disappeared overnight. At one point it was a very healthy, viable industry. You look back even further in WA, all we ever did at one point was kids TV and documentaries. They were the training grounds for everybody.

Now, all free to air content has gone. No one's making anything, and no kids TV. That's how hostile the government was. So, having Burke and Albanese felt like we're saved. ‘Oh, my God, the Messiah.’ Well, now it's not the Messiah. It's more of beware false prophets, because they fail to deliver.

One of the fundamental aspects of Revive was the implementation of quotas.

MF: Yeah, I recall ‘we're gonna implement it in the first 100 days.’

Then on the 18th of December 2024, seven days before Christmas, the Parliament of Australia posted a status update for local content quotas for streaming services, effectively saying ‘sorry. It's not happening.’

MF: And the thing is, we were all warned prior to this. Prior to the US election, there was a SPA call, and it was like ‘Okay guys, at the moment, the government's being very tentative.’ At that point, the polls were saying Trump would win. We were concerned of a Trump administration and what that would mean for quotas. ‘There's a lot of pushback coming out of the US, so the government is waiting to see what how the election pans out.’ That's the excuse that we're still getting; the hostility of the US, and all of the tariffs, quotas are bad for America. Well, it's only bad for the American companies that are using Australian owned infrastructure to deliver their product. That's the problem.

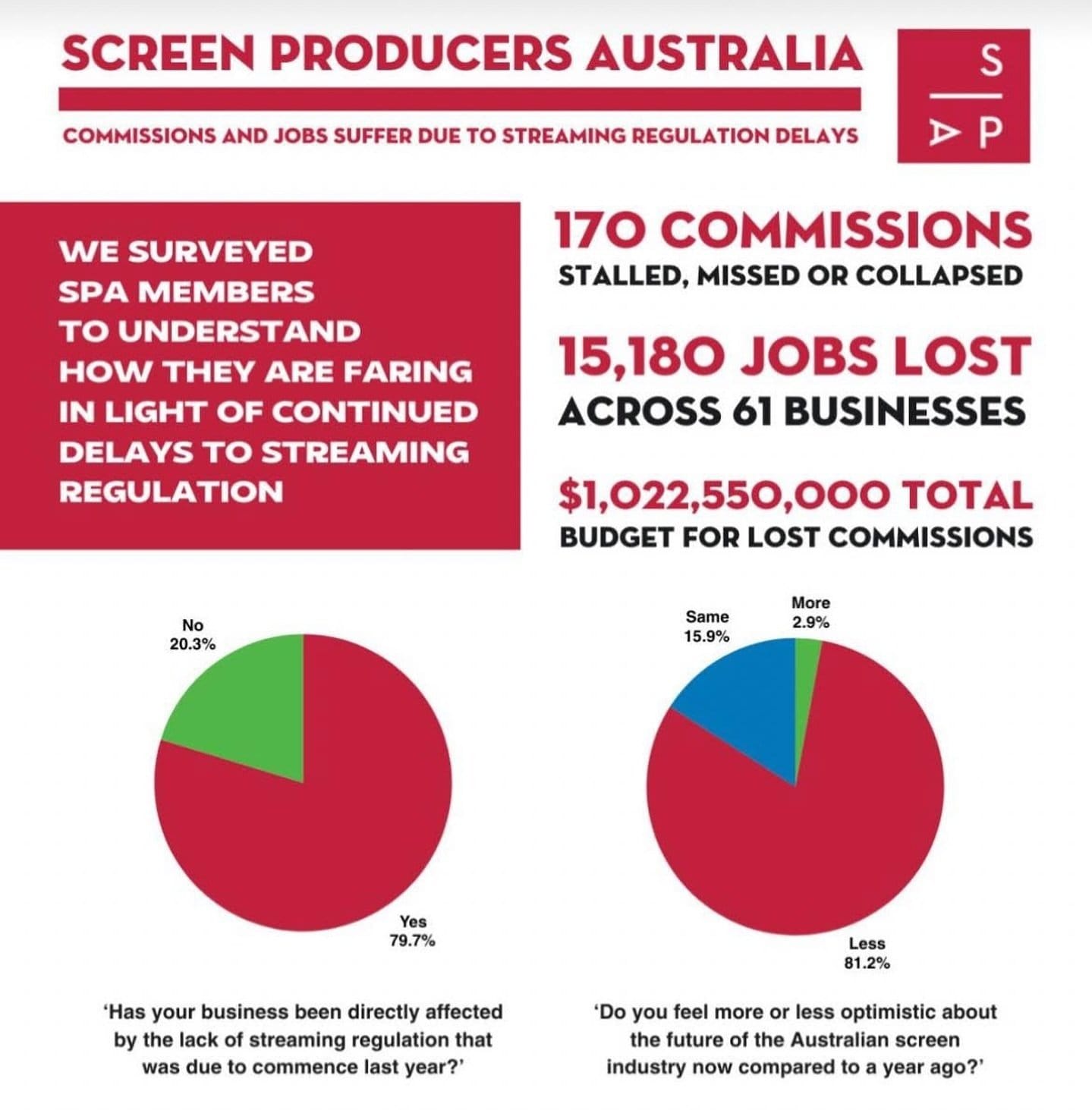

| Further reading: Content quota delays directly impacting nearly 80 per cent of SPA members: survey - Inside Film |

In 2022, the value of the film industry in Australia was $4.5 billion with 4500 companies registered in Australia to make film and television content.

MF: It’s frustrating. I mean, we as an industry employ more people than the mining and resources industries. You think of that, and you go, ‘why aren't we getting the same level of love and care as those sectors?’ We're certainly taxed more. A lot of those companies dig up all the resources out of the ground, ship it offshore, and they pay next to no tax, and they're all billionaires. But we ask for support, and we get told, ‘No.’

Is it a case of them seeing a $4.5 billion industry and thinking ‘you don't need support?’

MF: That's probably an argument they want to use. But without support, there is no industry. We don't have a population density to support the industry on its own. Exhibition in Australia is so hard because it's almost impossible to get our films into cinemas. We have to look at international markets to sell our films. We need people to be more aware of Australian made film and TV. I always look at the French model where 25% of any of their cinemas screen French films. What a fantastic rate that is. It's maintaining their culture. Now we've got kids that probably grow up with American accents, because the only kids shows they can watch are American.

| Further reading: What the UK can learn from France’s streamer regulations, Broadcast. |

On the flip side, the amusing thing is seeing Bluey being so eagerly embraced in America. Where there’s American accents in Australia, there’s Australian accents in America, because they're watching so much Bluey. Surely, as a litmus test, that would be a great example of saying, ‘hey, let's bring in quotas so we can have more shows like Bluey to export.’

MF: It's common sense, isn't it? You look at the success of breakout film and TV shows made in Australia, and you go, that's what we could have if we were making more of them, instead of just the occasional one or two. But also, we need to support what we make here and to also show it here.

People don't know their films are on half the time. Australians do go and see Australian film in a cinema. First, you’ve got to find a cinema that’s showing it, and you're one of two people there. It's like, where's the display and [advertising]? Why aren't we supporting what we have?

Back in the COVID lockdown, the cinemas were full. I remember going in to watch The Dry and it was a full cinema. ‘Wow, this film has been in three weeks in release and it’s a full cinema audience. Audiences are embracing us.’ In hindsight, that's when we should have had quotas put in place. Fast forward to now, and it's back to how we were pre-COVID. People want to see Australian films and TV. They just need to know it's available.

That’s the frustrating thing. I predominantly cover Australian films and I have no fucking idea when they're showing, where they're showing, and what festivals they’re playing at. At the very least, I should be one of the people who is in tune with where Australian films are playing. It’s gotten to a point where I now check key cinemas and film festivals a create a log of when they screen, because there’s no money for PR campaigns or coverage. That often falls to the filmmaker to do that legwork.

MF: Unless you're following the distributor or you're following the filmmakers on social media, then you don't know when these films are out. And a lot of the times you go, ‘Oh, my god, is that out already?’ How did I miss that? You just don't know. Marketing is a big thing.

Marketing Movies in Australia and Abroad

So let's talk about marketing. How much money do you get for marketing?

MF: Well, you get none. That's the problem. With your distribution deal, they’ve got to recoup the marketing expenses before you see a cent. So as any smart businessman will do, you want to cap those expenses because you want to be able to see a return on your work. There's $15,000 for a trailer, another $50,000 for posters to be distributed around. The costs are adding up very, very quickly.

The distributors paid $50,000 for the rights in Australia, and then they've gone and spent an easy $100,000 just on those things to market it. Now, all of a sudden, you've now got to recoup back that $150,000 before you see anything. But then, I’ve gotta get those trailers onto TV, so it’s whatever the networks charge, YouTube is basically free, and then to get it showing in cinemas before films cost money. You need to spend at least a million dollars to be able to market a film.

And that's before you've even earned anything back for the film itself.

MF: That's right. Who's gonna pay for that? The filmmakers have got no money. A lot of times they've either worked for a fee, which they've then reinvested so they've worked for nothing until that film turns a profit. So, they haven't got the money the distributors have just paid for the rights to that film in Australia. That’s $50-250,000 depending on the size of it. So, all of a sudden, they're in the hole for that. They want to try and recoup that as quickly as possible. It's horrific. It's a blood bath.

Going back to Tony Burke and that Rosemount presentation. Now, I’ve searched for him saying this on record as it wasn’t part of the main speech, but someone asked him about how Australian artists are meant to recoup these costs. His response was effectively that he wants Australian artists to be able to fail successfully. Meaning, they can spend the money they need to get their film, book, theatre show, whatever artistic endeavour it may be, out there and not end up broke or bankrupt at the end of the process.

MF: Wonderful. That is wonderful. I love it. In a perfect world, that would be great. You can't go to the bank after that, but everyone should be allowed to fail. If you fail in business, it doesn't stop you from starting up another business.

But this leads into another subject with film which is everyone's obsession with how much a film costs and what its box office is. Now, it infuriates me, because unless you're an investor in that film or involved in that film, why do you care? It's almost like the box office determines the quality. No, all it does is determines how many people went and saw it and how many screens it was on. Unless you paid for that, why do you care? You don't care how much a can of Coca Cola costs to make.

I get no financial impact from how well The Electric State did or didn’t do on Netflix.

MF: Netflix spent $350 million on their film. Who cares. They could have spent a billion dollars on that film. Who cares? They felt that they needed to spend that money. And that's what it costs. We don't question how much it costs to make a Toyota. The cost is the cost. Unless you're an investor in those companies or that film, it's not your business.

With Australian films, the taxpayer are [sometimes] involved, but they haven't fronted the whole budget. And a lot of the times, the Australian films make their money back in the long run. When we look at the Australian box office, we often talk about the death of Australian cinema because of low returns. You're looking at one market, like there's a whole world out there. A film can do $30,000 in Australia, and then it can pull 5 million in the US. If it costs half a million dollars to make, then that films now on profit, but everyone will just look at the failure in the Australian market.

https://www.instagram.com/p/DH69eqFTghk/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Adam Elliot posted earlier today saying that 1.3 million Mexicans have gone to see Memoir for Snail.

MF: Wow.

It screened in almost 700 cinemas.

MF: That's fantastic. That screen average is huge. That's nuts. That's a dream response with that many people over that amount of screens. It's fantastic. For some films, you go, ‘Oh, this movie only did $20,000 in Australia.’ But then it sold to 52 countries. That's a win.

If you look at something like The Babadook, and you look just at its Australian release, it made no money. It tanked. No one saw it at cinemas in Australia.

Jennifer Kent. What a fantastic talent. It was a terrifying film. Internationally, that film made a fortune. It made back all of its budget. It made a profit for everyone involved. It won awards and got seen internationally. That's a success. Just because you, me and maybe a dozen other people in Australia went and saw it doesn't mean it failed. It just meant it wasn't marketed right.

We have a bit of a tall poppy syndrome here, where films have to be successful overseas first before they're successful here. That's why a lot of Australian films are released last in Australia, because we don't go see them unless it has been recognised internationally. Wolf Creek took ages to come here. It was already huge in America before it's screened in Australia. Unless we get validated from international audiences, we don't care.

The international validation doesn't always translate to audiences. The problem then is trying to engage the Australian audience and get them excited or interested in Australian films again.

MF: That's true. That's really a lot people that when they think of Australian films, they go straight to a negative connotation. When Talk to Me had all that buzz, and everyone was saying ‘what a great A24 film it is’. That gave it clout in Australia. The rest of us were already excited before A24 even bought that film, but it took that brand recognition for the average cinema goer to go, ‘oh, A24, they're involved. That's that's got to be good.’ So it took that to get the real buzz happening for the average cinemagoer.

Brand recognition is its own stamp of approval. A24 of course, but then locally with Umbrella building up their brand identity with these nice physical media sets. That then flows to their streaming service Brollie, so it becomes an organic snowballing effect. Brand recognition has an impact, but it shows how difficult cutting through to a larger landscape can be. I know the audiences are dwindling all over the place, and maybe it's a cost of going to cinema, maybe it’s the cost of living crisis, but it's also the mindset of ‘it’s going to be on Netflix soon, so I’ll just wait.’ It’s that diversion of attention.

https://www.instagram.com/p/DH42923Tv1B/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

MF: You hear that horrible saying and it makes my skin crawl: ‘I'll wait till I can watch it for free on Netflix.’ You're not watching it for free. You're paying a subscription.

You've got to cut through the noise. And there's so much noise out there. Everything's vying for your attention and for you to spend your money. The thing is, even in the mining rich state of Western Australia, we're not rolling in buckets of cash. Some people are, but not most of us. So you’ve got to be very concise with where you direct that money. You're constantly fighting for space and release windows are a huge problem when you're trying to figure out when your film is going to be released. ‘Oh no, we don't really want to go this week because Fast and the Furious 26 is going to be out.’ ‘We’ve got Spider-Man this week.’ You're trying to figure out where you can get a window with clean air. It's becoming so much harder to find those windows now.

It feels like film festivals are the place where Australian films are given that space nowadays.

MF: That's where your cinephiles are going. People that love cinema are going to festivals. They're probably going to festivals because it's a better audience. They not going to be with the general public at the local multiplex. A lot of the bad behaviour in cinemas kills it. I went to a screening and the audience were just so disrespectful and rude; people were on their phones, people were talking. You've just paid $60-70 for your tickets, your popcorn and everything else, and then you've got someone ruining your movie because people forgot how to behave. That becomes a turn off factor.

I liked the April Fool’s Joke from Luna yesterday where they said they’d charge a $100 fine for anyone using their phone.

MF: I tell you what, that should be the policy. You turn your phone on in the cinema? That’s a $100 fine. It's all allocated sitting these days. They just ping it to your account. That's exactly what should happen. They’ve got to bring that in as a policy. All cinemas need to bring that in as a policy. It's a dark room and someone turns their phone on the check Facebook, and it's like, okay, you don't care about the movie. Just get the fuck out. Don't ruin it for everybody else. Seeing the blue light from your phone lighting up pulls you out of the moment. It does.

Australian Federal Election 2025

The Labor Party are asking the Australian public for a second term. Not everyone is a single-issue voter. We've got a lot of issues as a nation. However, if you're an artist or a filmmaker, you are going to focus on the arts. So, what’s on offer?

MF: In their recent budget, there's nothing. There's nothing. Not a single arts policy has been announced. The budget was quite disgusting for the arts in general. There's nothing in there for our industry. And yeah, okay, we've got a deficit now coming up after two back-to-back surpluses. Forecasts are pretty dire in terms of how we raise money.

There are certain budget measures they could have put in place well before the election. They could have implemented quotas. It costs the budget and the taxpayer nothing. It would actually allow for more Australian productions to be happening, which means more taxes, which means more income coming through, and then more Australian film and TV on screens.

| Further reading: 2025–26 Federal Budget released - Australian Government |

There is so much focus on ‘jobs and growth’. And that's important. However, it's for certain industries. It's as if you can't have a job in the arts. You can't envision a career in the arts. Matthew Holmes wrote a piece about how difficult it is as an independent filmmaker. People read that and ask, my kid wants to be a filmmaker. Why would I encourage them to go into this industry?

MF: I think the problem we have as an industry is we perpetuated the illusion of the glitz and the glamour. We've tried to sell the Hollywood dream. When people think of films, they think the Hollywood make it to those bright lights and the fashions and the fast cars and the money and the prestige. We've sold that. That's the dream we've sold. It's not the reality. The problem is, everyone thinks, ‘oh, you're a filmmaker, you're on $100 million. You're on Tom Cruise money or Chris Hemsworth money.’

Everything's about the size or the scale of budgets and who got paid what. That's why artists like us are treated the way we are, because [of the mindset that] ‘you don't need taxpayer money. You're making hundreds of millions of dollars.’ Well, no, you're not. ‘Netflix is throwing money around so you got paid.’ Yes, we're all on Tom Cruise and George Miller money. Of course, we are. We've all got multi studio deals.

No, we don't. None of us do.

Matthew Holmes has made four films. He's one of the 4% of filmmakers that have directed four films. The fact that most directors don't even get to do two films, let alone three or anything beyond that, that's a huge problem.

Filmmaker Matthew Holmes shares an open letter to the filmmaking community and industry leaders

No one's getting paid. We saw it with The Brutalist where the director of that didn't get paid. In the films we make, we've invested our fees back into them. I look at the fee I'm getting for the next film, and you look at that on paper, and you go, ‘Oh, wow, that's so nice. Fantastic.’ Then you go, hang on. Divide that by the five years I've spent in development. Then if we shoot this year, and then we say, we get it released in two years time. So now divide the number by seven, and I would have made more money on the dole than I would have done spending all my time on this project. That's the reality.

We don't do things for the money, because I could go stack shelves at Kmart and probably make more money. We do it because we want to tell stories. The financial hope is really to earn enough as a wage or a fee to keep the lights on, to put food on the table, keep a roof over your head and keep going on to the next one. That's the reality; you scrimp and save and scramble to stay just above water to keep doing it.

Shifting for a moment to discuss the antagonistic way that Meta scraped the library of Australian authors, one of who is your great grandfather.

MF: It's infuriating. You have a multi-billion-dollar organisation or organisations stealing. Their advisors would have said, ‘oh, it's gonna cost too much money to license all this.’ Everyone else has to license it. They just decided ‘we make our own rules.’ These tech bro companies are like the old Silicon Valley and hedge fund managers. They're above the law. They can do whatever they want because they've got the money and the resources to get away with it. And now they're stealing work to train AI systems to use that to replace creators. That's the ultimate end goal.

They're not creating these systems out of the kindness of their heart. They're creating something so they can sell it and then use it to replace people so they don't have to pay. That's the end game and they’re stealing the work of authors to do so. The fact that there's class action lawsuits being filed in the US now, means that the Australian Government, publishers, authors, everyone else affected, should be getting involved and suing these companies into oblivion to send a very clear message that says if you're going to steal our work, you must pay the price.

We can work out license agreements. That's the publishers and distributors jobs. They can work that stuff out. But then why would we want to sell our stuff to a system that's designed to try and replace us? It will come for the film world. You're seeing a lot of AI generated videos happening now, and it's soulless, generic rubbish. But the fact that it's gotten to this point now, in terms of quality, is quite scary. What could happen? The next thing you know, films will be made by a bunch of prompts, and then the whole of the arts is gone.

Labor have been deep in election campaign mode, and they’ve posted a few AI generated images which feel soulless.

MF: So many major organisations are using AI generated art. I got really annoyed with the ICC, the International Cricket Council, because all of their promotional material and artwork is AI generated. An organisation of that size, which is worth billions of dollars, plays to billions of people around the world, is using AI generated art. They couldn't afford to get a graphic designer? Seriously?

The same as any political party. If you're not going to pay and employ an artist to create this stuff for you, there's a problem. It just shows a total lack of respect for the art form.

The problem with AI is it it's like, ‘oh, why should I pay someone when I can just type a few prompts in and eventually get what I want.’ Well, no, that's not how it works. People make their living out of this, and there's no better way to create a piece of art than using the human soul. A world without art is a very dark and depressing place; get rid of music, get rid of books, get rid of magazines, get rid of posters, get rid of images, that's all art that's created by artists. Take all that out and what have we got?

Is there a political party that is supporting artists? And if so, who are they?

MF: Senator Hanson-Young has always been a big advocate. The speech that Jacqui Lambie did is exactly what we should have been having from Burke and Labor over the last three years: someone fighting for our industry. She's the only one.

https://www.instagram.com/reel/DHne4WQCFl6/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

With this upcoming election, through the whole rezoning, I've been moved into the electorate of Swan. I've reached out to the three candidates that are running in that electorate for this election. There's Labor, there's Liberals, and then there's the Greens. I've written to all three of them. The Labor candidate isn't able to meet with me until after the election if they win their seat. They're the current sitting member. Their office also said that not a lot of people advocate for film and TV quotas and supporting of the arts, which I thought was hilarious, because a big part of her electorate is Victoria Park and the 100 people that I know in the film industry that live there, apparently none of us are advocating the sitting member for the Federal seat of Swan. There's a hint there for people to start writing to their local member.

Their office then forwarded my email to the Member for Burt, which is Matt Keogh. He sent me an email two weeks later in response reaffirming that the Albanese government is committed to quotas, and they're working on it, and it's just the consultation process taken longer than expected, but they will be pursuing it. So very much a stock standard reply. At least he came back with a reply.

Mic Fels, the Liberal candidate, no response. I then sent him a message on social media. The lovely thing of social media is you can tell when they see your message. He saw the message going ‘hey, I'm just following up on my email I sent you on such and such a date.’ He’s seen it. No response. I then sent another following up email, no response. So I then sent him an email last night saying this is going to determine how I vote on the election. No response. The Greens, I emailed the candidate through their campaign office email. No response. I followed up, no response. So I've got three candidates who do not give a shit, so I'm in a bit of trouble.

| After this interview, Michael noted that he received phone calls from Minister Matt Keogh to discuss issues within his electorate. He also had a 'constructive and positive' conversation with Zaneta Mascarenhas where the local member noted their passion for the arts and will advocate within the Labor party for more support. |

Again, the 2022 figures state this is a $4.5 billion industry. Yes, it’s one electorate, but still.

MF: That's right. The electorate of Swan runs through Midland, through Victoria Park, through to South Perth. It’s huge with a mix of very wealthy to working class to very poor. There's a mass amount of demographics in there. The arrogance of the sitting member, that doesn't sit well with me, so I cannot support that member. If that's the arrogance of the member in my electorate, I can't even risk rewarding that arrogance. But then it's like the other two? I'm already risking a lot, because I know what nine years of Liberal government was like for the arts. Do I really want to gamble another three years of that? Not particularly. The other option is The Greens? I love the Greens for their social justice and the social policies, but the reality of the real world and a lot of what they want is just not practical.

We have got to get rid of this two-party system. That's our problem. We do need people to vote in independents and the smaller parties. I think the best outcome is a minority government, where the balance of power is spread out and they have to negotiate between themselves. I think the most successful part of Australian politics was the minority government of the Gillard years. I know more legislation was passed in that term than any other term in history because the parties had to work together.

The Australian Labor Party are very much like the American Democrats. They know what to say when they need to try and win, but when they have power, they don't know how to use it. Then they miss their chance, and they get booted out, and they sit back and whinge and carry on from the sidelines. They don't learn the lessons as to why people voted for them in the first place. As soon as they get power, they forgot about what put them there, and they seek their own goals and agendas. Unfortunately, that's what the Albanese government did. They had a huge swing towards them from the Morrison government. A lot of people voted for Labor for the first time in their lives at the last federal election because they were so sick of Scott Morrison and his government. The guy was the Minister for nine different portfolios, the lies, the cover ups, the scandals.

Then Labor takes this massive win and goes, ‘oh, it's because people wanted us.’ No, we didn't want the other guy. We couldn't do another three years of that. But they didn't take that message. They just took the message of ‘as long as we're better than him, we're in.’

We won't get in depth into this, but the number one pillar in Revive was embedding First Nation culture into everything. This was alongside the notion of embedding culture into all aspect of decision making. These are great pie in the sky ideas, but unless you actually act on them, they won’t happen.

MF: So many things have to be market led as well. There's no point in just making stuff for the sake and making it. We got to try and make things for audiences. Screen Australia have tried that, but then again, their own funding programs go counter to that.

There’s a new head of Screen Australia, Deirdre Brennan.

MF: Hopefully. I've never received a cent from Screen Australia, so I'm always hopeful. Screen Australia have really been a closed shop for me. They aren't really interested in genre films. Executives have said to me that if the market wants that, the market can pay for that, which is true. Things should be market led, because that's how you get to audiences. You want to make stuff that audiences want to see, but it's kind of also self-defeating to be going ‘if that's what you want to make then if audiences want that, the market will pay for it.’ That sort of says that everything else that you're funding, audiences don't want. That does come to our disconnect. Every now and then, a gem will come through.

Audiences have been betrayed a lot over the years. With Australian films, we made a lot of shit. I don't talk rubbish about other people's work, because no one sets out to make a bad film. Ever. Ee don't get up in the morning and go, ‘how can I make the worst fucking film in history.’ We do not do that. We have a reason for telling what we want to make, but we have a lot of hit misses, and it's almost like a lot of stuff rushed out, and the time hasn't been taken. A lot of it is because the money is getting shuffled out the door, and a group of people are just catching all that money and just going to make whatever they want.

Again, people don't have the chance to make mistakes.

MF: No, you're not allowed to make a mistake.

The first one's got to be great. When you look over to America, you can make shit after shit after shit.

MF: In America, it is very much business driven. You can fail. Some people only get one chance. It comes into the business plan. I always say to young directors, what's the business plan? It's all well and good having the art, but what's the selling point? It comes down to risk. If you're going to blow $10 million well, make sure you blow it spectacularly so it's memorable. And if it does fail, and if it's a memorable failure, you can still trade on that. If it becomes a bit of a cult hit, or if it finds an audience later, you can trade on that. If you blow $10 million and no one has heard of that film, you've got a big problem. If you're going to fail, fail big. Don't leave anything on the table. Throw everything you’ve got at it, and then hopefully it all comes together.

Let's end on something positive. What is something good that's happening in the Australian film industry right now?

MF: There are so many new stories and new voices being discovered. There's more indies out there making films. People are moving away from the agencies either out of frustration or the need to tell the stories they want to tell without restrictions. I think we're in a creative boom.

Here in Perth, there's more films in production than I can recall. We were lucky to do one film a year, or a kids show, a documentary. Now there's so many things shooting at once, there is that genuine hope and employment, which is always wonderful. There's a lot of stuff happening. There are so many new voices coming to the table. There's these young filmmakers coming out who are unshackled, and they're taking risks and that's exciting. They’re the future voices. Even the older filmmakers are getting their first shot. People that have been cutting their teeth for 20-30 years are now getting a chance to finally make a movie. We're growing.

This is a very precious moment where we’ve got everything against us, and we're persevering despite all odds. It does give us hope that even if we get betrayed and failed again by a Labor government, that we're still going to find a way. I hate to quote that line from Jurassic Park, but film will find a way. I think every storyteller will find a way to tell their story. We might not get the resources that we need to do it, but we'll find another way. We might not be as big and bold and ambitious as we wanted, but we'll find a way to get it seen, and that's how we've got to look at it.

We can't sit back and bemoan the fact that we didn't get funding or we didn't get support by a government agency. We’ve got to find a way to tell our stories, and if that means we're putting it on a smaller canvas, or changing who we put in it, or things like that, that’s what we’ve got to do. We’ve got to be nimble and not let the obstacle stop us.

If you want to tell that story, you'll find a way.

Michael Facey can be found on Instagram here.

At time of publication, neither the Australian Labor Party or the Liberals have announced arts policies. This interview will be updated if they are announced during the campaign.

[i] Revive: a place for every story, a story for every place https://www.arts.gov.au/publications/national-cultural-policy-revive-place-every-story-story-every-place; Accessed 14 April 2025

[ii] Trump Tariffs: Australia Holds Firm on Local Content Quotas Despite U.S. Trade Pressures; Variety:

https://variety.com/2025/tv/news/trump-tariffs-australia-local-content-quotas-1236358525/; Accessed 14 April 2025

[iii] Australian artists only earn $23,200 a year from their art – and are key financial investors in keeping the industry afloat, The Conversation: http://theconversation.com/australian-artists-only-earn-23-200-a-year-from-their-art-and-are-key-financial-investors-in-keeping-the-industry-afloat-228792; Accessed 14 April 2025

[iv] Labor’s Albo Figure: https://www.instagram.com/p/DIQjE8CMgl-/?utm_source=ig_embed&ig_rid=10dccafa-3696-4495-87af-2dff3167ab50 & Liberal’s anti-Albo figure: https://www.instagram.com/p/DIQl20QzfxH/?utm_source=ig_embed&ig_rid=7d8773d6-21ef-42f6-979d-fb48847eeb5f

[v] At time of writing, I still only have five toes on each foot. Good. I can’t afford new shoes.

[vi] Labor considers an artificial intelligence act to impose ‘mandatory guardrails’ on use of AI, The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/article/2024/sep/05/labor-considers-an-artificial-intelligence-act-to-impose-mandatory-guardrails-on-use-of-ai; Accessed 14 April 2025

[vii] Federal Arts Minister Tony Burke spoke to ABC Arts about the theft of creative work, outlining that there was nothing the Australian government could currently do to prevent unlicensed use of work to train AI models.