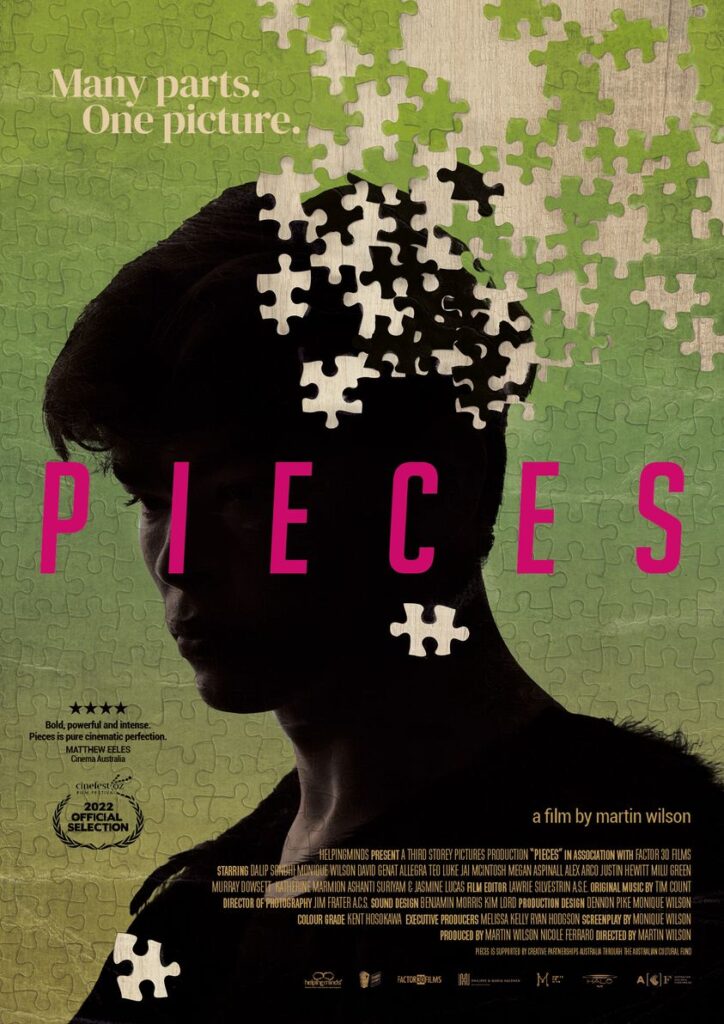

You might know director Martin Wilson for his debut thriller Great White, but with his latest film Pieces he’s keen to show that he’s not just ‘the guy to make the shark film’. For his sophomore film, Martin and producer Nicole Ferraro paired up with screenwriter Monique Wilson to bring a respectful and tender portrayal of mental illness to screen. Shot over ten days in their home town of Perth, Western Australia, Pieces tells the story of an art therapy class and the interconnected lives of the people who utilise the facility to help ease their lives living with mental illness.

Pieces is a proudly Perth-local film with an impressive ensemble cast that includes stunning performances from Luke Jai McIntosh, David Genat, Monique Wilson, Milu Green, Alex Arco, Allegra Teo, Megan Aspinall, Dalip Sondhi, Ashanti Suriyam, Katherine Marmion, Justin Hewitt, Murray Dowsett, and Jasmine Lucas. It was made in collaboration with Helping Minds, a not-for-profit organisation that provides mental health and carer support services in Western Australia.

Pieces launched in Perth on October 6th to help celebrate Mental Health Week, and will run with local and regional screenings around Western Australia, Sydney and Melbourne from October 8th. Visit the Pieces website for further information.

Martin and Nicole caught up with Andrew to discuss the importance of opening up about mental health on film, the production process, and about the truly impressive dance sequence and costume design for the climax of the film.

This interview has been edited and condensed. Andrew F Peirce works at the Mental Health Commission but is not associated with this production in any capacity. All thoughts and opinions are his own.

I’m curious about the relationship between yourselves and Helping Minds how that came about, and where the discussions started between you both for pieces?

Martin Wilson: It started because I was doing a lot of commercial/corporate work for HelpingMinds as a director. We were shooting these mini documentaries called ‘Real Stories’ across the state that focused on the lives of carers for people living with mental illness, and also people that had their mental health challenges. These mini docs were very successful for Helping Minds and were nominated for an Australian Directors Guild Award which helped established my relationship with HelpingMinds. As I have a lived experience with my brother, who lives with schizophrenia, so I had a passion for this social topic or crisis. And it seemed to be a good mix for me.

I always wanted to do a film around mental illness and help get the message out about the complexities and increasing issue in the community. So I pitched an idea to Helping Minds which was originally a series, which morphed into a 24-minute film. And we just felt that to get this message out there – to get people talking – I felt a feature film was the best medium for it to be noticed, so it just expanded from here where writer Monique Wilson worked at expanding the project into a longer narrative which eventually became a 95-minute film within the initial main unit, five-day shoot, and then then we did some pickups with a crew of three people over the next five days.

Nicole Ferraro: Debbie Childs, the CEO for Helping Minds and their board led by Franco Guazzelli, got right behind Marty and the idea of the film, Debbie really believes in Pieces and it’s amazing to have somebody like her see the value of film as a conduit for change.

MW: Once we finished the film through Debbie’s connections we screened it to the Mental Health Commission and the West Australian Association for Mental Health. We didn’t want it to be all bleak and black, we wanted to put a lot of heart behind it. And but we also wanted it to be authentic as well so it had to be pretty confronting and raw as well. Real life is not all black, it’s not all white, so we tried to have nuance in there. Mara Pritchard at the Mental Health Commission and her team were impressed by the film and its intention. The Mental Health Commissioner Jennifer McGrath felt that that was the film was what they’ve been looking for to open Mental Health Week.

People can have days of depression and anxiety and stress. And then once the panic attack, or the anxiety attack has dissipated, an hour or two later, that could be having the best day of their lives. That’s certainly my personal experience. I’ve had panic attacks, and then you’re having a wonderful time at the end of the day. You’re not always just sitting there in the depths of depression and despair. It’s a roller coaster.

MW: One of the key reasons we made the film is that we wanted to take away judgement for people. We don’t label the various challenges that people are going through. We want people like yourself to speak openly and honestly about their daily experience and not be judged for it. We want people to see people that are going through the challenges as normal. That stigma really exists and we wanted to start that conversation. I love it when people talk very openly and honestly about it and the sense that you’re not going to be judged for it. People do have these moments, but it’s not always going to be like that.

NF: The characters are not defined by their diagnosis. The film exploresthe relationships between the carers, and the people living with mental illness, the friends, the people around them, and what that experience might look like for a day.

The performances are very vulnerable. How did you get the cast to that point where they were able to access those kinds of emotions?

MW: That was the biggest thing for me because I knew I didn’t have a lot of time on set. And I knew I had to make sure that the performances were very real and authentic so people could believe that this happening in the community. We worked with Annie Murtagh Monks as the performance coach, spending a week before shooting, really teasing out the characters, going through in great detail every scene every character nuance. I also made sure that the actors did detailed research into their characters, and really knew who they were playing and why they were playing them. That was critical, because a lot of the film was built around a pseudo-documentary approach. Because we didn’t have a lot of time. I was asking very off the cuff questions, but because the actors really knew their characters, inside out, the answers they gave in those pseudo-documentary moments came across as very real and raw. I take my hat off to the actors and how committed they were for Annie to come in and really work with being truthful in the moment and owning the moment and being authentic at all times. We’ve had comments where people didn’t know that these people were actors, which is the best thing for us.

Nicole, being a producer and trying to wrangle a production in such a short period of time, how do you balance everything going on, and getting everybody in the right space over ten days?

NF: Marty and I sat down and thought, “How are we actually going to do this because this is really ambitious?” Communication is the first thing. I tried to have transparent conversations as early as possible with people to explain what we wanted to achieve. Michael Boyle, who was our first AD, he was sensational on set and making our schedule work. I can’t wait to see what he does in his career. Lauren McDonough, who was our production coordinator, she’s one person that works very similar to me, so we bounce off each other and she worked hard to assist in keeping the cast and crew supported on set. I spent most of a decade being crew side, so I have some understanding of what the crew need. Working with DOP Jim Frater, we tried our best to equip the camera department to work quickly.

MW: With Jim, I knew he’d done The Heights. He’s brilliantly talented with no ego. It’s a nice combination to have on such a tight shoot. He’s very giving and extremely generous. We went down the Cinéma vérité approach of handheld, and whatever we got with two cameras, we got. We just basically blazed away and went for it.

NF: We had to be pragmatic where we put our resources on Pieces with the micro budget and shooting schedule. We kept the locations to a minimum because we didn’t have those extra hours to move around. I think we were averaging somewhere between 11 to maximum of 17-minutes a day. It comes from the willingness of the team that you’re working with who have great problem-solving skills, because you’re asking a lot of them. It’s a team effort. It’s being clear on the desired outcome, communicating to them what we need, and asking them how we can help them achieve that.

What lessons did you learn from doing a shark flick to a film about mental health?

MW: To me filmmaking is about a good script and good performances. And I’ve been focusing on that for so many years and I knew that that’s what a director gets judged on. What I did learn with Great White was that films are made in pre-production. Script writing isn’t the most expensive part of the process. Nicole and I, we had very minimal locations, and we workshopped the actors, and we did all those things that made the process of shooting reasonably doable.

All those craft levels that I was doing in Great White – which is more suspense and action – a lot of time these people are on a raft, so I had to make sure to the best of what I could do that the performances were solid. All these craft aspects moves over to these other films like Pieces, and I wanted to showcase that. I didn’t want to be pigeonholed as being ‘that guy to make the shark film’. There’s a lot more to me and a lot more to our team than that. Pieces is a very personal film for me and many people on the crew, people put a lot of heart and soul into Pieces. I want to be practising directing, because you don’t get many opportunities at it, so the only way to get better is to just get out there and do it.

I had such a passion for this because it was such a personal project. It’s the one project that I was going to do on a micro budget. And I was going to throw every ounce of my 25 years at it. Fail or don’t fail, I was going to have a crack at it. It was very, very different mate. I didn’t have the machine behind me that I did on Great White. But it was also very freeing because on the pick-up shoots I just went back to my uni days at Murdoch, when I had three crew and I could just move and get shots really quickly. I could shoot rehearsals. All the parameters of a multimillion-dollar film with a large crew, were not there on those days. Although the first five days were very full on and still quite structured.

NF: It’s worth mentioning the composer, Tim Count and editor Lawrie Silvestrin came on board to Pieces, and that is purely because of the relationships and the collaborative work that Marty did with them on Great White.

Location – Perth, Western Australia

© Copyright – Third Storey Pictures Pty Ltd.

Photographer – Martin Wison

MW: It’s such a WA film. It is a community-based film. It’s a film where we had all WA actors, all-WA crew, all WA post-production. And these are all from relationships that we’ve built up over 25 years. Ben Morris, who did the sound design along with Kim Lord, who were just amazing in what they gave to the film in terms of being so generous. It’s really important that we do these films and showcase local talent.

You showcase Perth in a way that we rarely get to see. It looks beautiful. That’s what I loved about The Heights was that we get to see the suburbs, we get to see the streets, you get to see the side of Perth that we don’t usually get to see. The aerial shots make the city look beautiful. It makes you feel proud of the place that you live. You did a great job.

MW: Thanks so much. We often get that common feedback about Scott Slawinski’s drone footage which was incredible. The reason I got to know Scott was because he’d done this ‘May the Fourth Be With You’ movie (Cloud City Chaos) which was shot all around WA and had a Wookiee in it, and I thought that was amazing. I contacted him on LinkedIn, and then got him on to this film. I’ve also done a commercial with him. That’s the other thing coming from TV commercials is that in WA you’re trying to maximise production values with tight budgets. And just doing that for years and years and years and getting it drilled into you, you try and spit it back out into a film. Scott just had a different eye from an aerial perspective and I wanted to showcase Perth as an evocative, richly coloured and diverse metropolis that people hadn’t seen before.

It could be a different city. And I think when you’ve got no money and when you’ve got no time, you’ve got to have some X factors that you’re trying to dig out of nowhere. It was kind of like trying to give it a bit of an international lift.

NF: Kent Hosokawa did the grade and it’s so beautiful and rich and really enhances the film. The sound design team – Benjamin Morrison, Kim Lord and their crew – created the sounds of the city, it’s got so much energy.

MW: Kent had come from The Heights, so he’s another one that hadn’t done a feature before. I wanted a real surreal, glossy, artsy look, and we just hit it off. I just can’t believe how good a job he’s done with some very challenging images. Coming from TV commercials I’m a big fan of Tony Scott and the way he approaches shots and colour grading. The DOP Jim Frater sometimes didn’t even have any lighting. This is indie filmmaking. We even used a wheelchair at some point, which I know they used to do in the 60s, when we’re doing some dolly shots. So that’s our going down to the chemist and hiring a wheelchair. It’s low budget.

I want to talk about the stunning costumes. In particular the beautiful Alexander McQueen-style clothes that Tom wears [Luke Jai McIntosh]. Can you talk about the costume design and how important it was to get that look spot on?

NF: It started organically through the pre-production process. Monique Wilson, the writer, knew the characters and was working with the actors during rehearsals and had some great ideas. She found some key pieces and it grew from there. She also worked with artist Kristie Rowe, who made the wings and the headwear in the dance performance as well as of Tom’s pieces. They both did an exceptional job.

We also wanted to minimise changes, as changes slows things down and can inhibit the options in the edit. Every character does have an iconic look, which is an important thing for an ensemble cast. This is also through Hair and Makeup artist Tess Rowe who collaborated with Monique and the cast to help build the characters.

Australian films don’t get very many dance sequences at all. I kind of wish that more films embraced dance sequences. I was so thrilled when at the end, this closes on a great dance sequence that reflects the themes of the film. How did the choreography and the discussions around presenting the dance sequence go?

MW: It was very much Monique, she had some dancing experience, and Ashanti Suriyam is a dancer and has a dance studio, the Dance Workshop. She played Laya in the film. And so, Monique worked really hard with Ashanti to choreograph the dance sequence to make it as cinematic as possible working closely with Jim Frater to capture it. The key about the dance pieces is it reflects the themes and the story of the film, which is about regeneration, hope, empathy and compassion and connectivity between the community and how you get through all these challenges. We wanted it to be very dynamic, and also reflective of the arc of the character so there’s a growth in that dance. I think Monique could describe it a lot more eloquently than me. Even though there is tragedy, the final dance piece is joyous. And it reflects the final scene where the mother and the daughter find some common ground.

It morphed and changed a lot made from the 24-minute to how it was constructed at the end for the 95-minute film. My background is nowhere near dancing and theatre, I’ve come from commercials and sharks to dancing, so it’s a very different piece. I’ve got to thank a lot of the people that did the dancing and the choreography and the way Jim shot it. And the way it was cut by Lawrie was magnificent.

However, some of my favourite film are musicals. I love some of the Judy Garland musicals, Easter Parade is one of my favourite films. Musicals are very cinematic, those Hollywood musicals. Spielberg did that in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom at the start, that was his crack at doing one of those big 50s set pieces. They’re big, cinematic dance sequences. They’re like a chase sequence. They’re cinematic in the construction because you’re trying to tell a story through dance, with no dialogue and you’re doing it with cameras and editing.

NF: It demands a different lighting set up and it evokes different emotions through movement, free of dialogue.

I always think of Slumdog Millionaire and that is a film where you follow the highs and lows of this character, and then it ends with this dance sequence. It’s a freeing thing. It’s a different way of expressing ourselves. And that was why I was so appreciative of seeing it at the end. We can say all these words, we can say all this stuff, but then sometimes, the only way that we can truly express ourselves is by movement. I was quite moved by that.

MW: It’s great to hear, because it’s a risky piece. Everything that you’re saying is why we did it. Thinking about cinema, again, it’s often what we say, what is the story of the visuals. It’s always great when you pull back the dialogue, and you let the camera and draw you in. It was really interesting.

Location – Perth, Western Australia

© Copyright – Third Storey Pictures Pty Ltd.

Photographer Graded Frame Grab (Jim Frater ACS DOP)