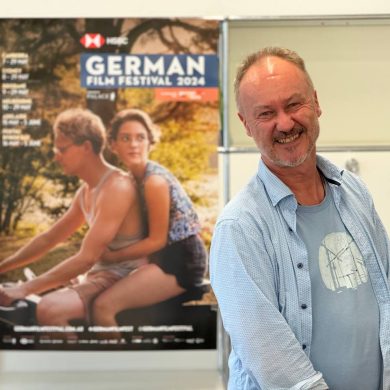

Before embarking on this piece, I want you to ask yourself: what was the last Canadian film that you watched that didn’t have the Cronenberg directors name attached to it?

Take your time. Keep those names in mind.

On we go:

Early in David Stratton’s second book, The Avocado Plantation, he writes about the removal of the 10BA tax incentive, and what kind of impact its dissolution might have on the Australian film industry. He rightfully criticises the incentive, highlighting how some ‘production companies’ manipulated it for personal gain, effectively creating filmic versions of unwatchable trash that would never receive a proper release platform, while also highlighting how important it was for sustaining the Australian film industry. Doing so, Stratton ties a line between the Australian film industry and the Canadian film industry, keenly sounding an alarm that the Australian film industry runs the risk of collapsing into anonymity, much like the Canadian film industry did.

He writes:

The destruction of the English-speaking Canadian film industry during the early 70s by just such a policy of tax concessions and an open go for foreign actors, had been well documented: Canada still has not recovered from that dreadful period.

The Avocado Plantation, David Stratton

If we take that statement in isolation, remove it out of time, it feels applicable to the current Australian film landscape, where the notion of what constitutes an Australian film is gradually collapsing before our eyes.

If that sounds alarmist, then I assure you, it is.

I want to focus on the Canadian film industry for a moment, as it feels like the closest film industry to the currently amorphous Australian film industry. If we think of what a Canadian filmmaker is, we often come up with the same handful of names: David Cronenberg, Atom Egoyan, Guy Maddin, Xavier Dolan, Sarah Polley, and Denis Villeneuve. Out of that bunch, maybe Cronenberg and Villeuneuve are considered ‘household’ names, as in, if you mentioned their filmography, people would be aware of Videodrome or Arrival. Sure, the others have #FilmTwitter cache, and are greatly appreciated by the broader film loving community, but their impact on the casual film loving community is rather muted.

If we then broaden our purview into how the Canadian film industry presents Canadian culture on screen, well, depending on your appreciation and experience with Canadian films, we find ourselves slightly lacking in this regard. While films like Goon and its sequel, masterfully employ Canadian actors and talent to tell a narrative that’s defiantly Canadian (after all, ice hockey is the AFL of Canada), and proudly so, we can’t particularly glean the same appreciation of Canadian culture from films like Antiviral or Hobo with a Shotgun.

Xavier Dolan’s filmography has long found fertile footing in Canadian culture and society, with Mommy in particular working as a critique of Canadian politics. Denis Villeneuve’s Incendies delicately combines Canadian culture with a global refugee legacy, leaving a masterfully devastating impact on the viewer. Then there’s Patricia Rozema’s powerful drama, Mouthpiece, a film that appeared at TIFF in 2018, and in the year 2020 finally received global attention thanks to the exhaustive and impressive support from Canadian website, Seventh Row, whose in depth coverage helped usher in a global appreciation for the indie film, leading to UK film critic Mark Kermode helping champion it for a UK audience.

For a country that has one of the major film festivals that is used by Hollywood as the launching pad for Oscar-friendly fare, the Toronto International Film Festival, it’s a cruel shame that the global awareness of the output of the Canadian film industry feels deceptively muted around the world. We so often hear about how well films like Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri and Jojo Rabbit were received at TIFF, but outside of this, there’s little awareness of Canadian films. As an Australian, I’ve grown to rely on independent websites like Seventh Row who have come into play with their tireless championing and support for smaller, independent Canadian films that we would otherwise not hear about.

(As an aside, this fascinating read about the production of an ice hockey musical called Score: A Hockey Musical (featuring Australia’s own Olivia Newton-John no less) digs into the difficulties of producing Canadian films for Canadian audiences.)

On the Wikipedia entry for the ‘Cinema of Canada’, the varied reasons behind why the Canadian film industry struggles to gain attention are laid bare. Two fields are worthwhile highlighting:

- Films labelled as American films could often be better described as collaborations between Canada and the US. In addition, films which are sometimes designated as “American” productions often involve a higher-percentage of Canadian participation but the “American” designation is favoured for tax purposes. Also, unlike other countries who tend to have citizens with discernible accents, the American media too rarely highlights or identifies actors, directors or producers as Canadian in origin, leaving the false perception that few Canadians work in the industry.

- In a phenomenon which can be likened to the theory of cultural cringe, a considerable number of Canadians reflexively dismiss all Canadian films as inherently inferior to Hollywood studio fare. This is not necessarily connected to reality, as many critically acclaimed films have been made in Canada, but the idea nevertheless presents a significant hurdle to Canadian filmmakers seeking to build an audience for their work.

If we sub-out the word Canadian, and insert the word Australian, then we’re pretty much in line with the current reality for Australian cinema.

The excellent web-series Every Frame a Painting covered the subject of international filmmaking in Canada in the creatively titled video, Vancouver Never Plays Itself[1], showcasing in surprising depth how the city of Vancouver subs in for cities around the world. Now, this isn’t a new thing, as anyone familiar with the process of filmmaking would appreciate that cities all around the world have been substituted for other cities, with everywhere from Romania to England swapping out their home locations for (usually) American locales. But, as Tony Zhou explains, Vancouver is often presented in make-up, never allowing its true self to appear, and in turn, effectively nullifying Canadian culture on film.

With many of these American-Canadian co-productions (like the ironically-applicable-to-this-piece Saw film, made by Aussie filmmakers James Wan and Leigh Whannell) utilising Canadian crews to make American-facing productions, it’s no wonder that the Canadian film industry struggles to pull itself out from underneath the behemoth of Hollywood and into its own deserving spotlight. While we can easily point out the reality that French-Canadian films can sometimes ‘backdoor’ their way into public consciousness via the Francophiles of the world, with films like Incendies and The Barbarian Invasions, each receiving global acclaim and accolades as a (cringe) ‘foreign language’ film.

For film viewers, they see films like Chicago, The Incredible Hulk, Mean Girls, and Good Will Hunting, as being proudly American films. And while they are technically American stories, with American actors, set in American cities, these films were shot and made in Canada with Canadian crews. It may be great for the Canadian film industry to have these mammoth productions made there, but it leaves little for the Canadian identity, which leads into the heightened feeling of ‘cultural cringe’ for Canadian audiences.

As per that Wikipedia entry, ‘this is not necessarily connected to reality’, but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist. Globally, we have become so attuned and accentuated to the American dialect and style of filmmaking, that when presented with our own countries fare, we often neglect it, thinking it to be inferior or lacking in the shadow of our Yankee friends. If I think of my knowledge and understanding of the Canadian identity on film, the first images that come to mind are Terence and Philip and the Canadian Mounties of Due South. I know full well that there is more to Canada than these characters, but additionally, I’m certain it’s hard for international audiences to shake the leather-skinned ockerisms of Paul Hogan and a certain knife in New York.

In many ways, the American identity has become the default, much in the same way that the American film industry has become the default. Hollywood is not the originator of film – it was, and always has been, a global art form – yet, the manner that financial decisions are made about film seems to be predominantly focused on how far the US dollar will stretch. Where many countries like the UK, Canada, France, Australia, and New Zealand, have film industries established and supported by the government, America’s film industry is one propped up by the balustrades of the studio system.

With behemoths like Disney and Warner Bros. that appear to have their own Smaug-protected moneypits, it’s understandable why they would look at the rather affordable options of filming ‘internationally’ (even if Canada is right across the border). Additionally, given the assured promise of Hollywood productions, and the guarantees that come with cash-loaded producers, it’s understandable why countries like Canada and Australia would want to sidle up to Hollywood to ensure film production crews stay employed. It’s pretty much guaranteed.

That’s where we’ll leave our Canadian friends for now, as we head down to Australia, the country that may as well forever be collectively known as the ‘Vancouver of the Southern Hemisphere’.

In the year 2021, we’ve already seen a bunch of American films made in Australia with Australian talent, crew, and partially financed by Australia state and federal governments. First, we have Godzilla VS Kong, which, like a previous film in the series (Kong: Skull Island), utilised parts of Queensland for its production. Then there’s the dystopian monster-romance flick, Love and Monsters, which was filmed in Queensland, and showcases a world that’s overrun by giant monsters, leaving humanity threatened (jeeze, almost like we’re seeing a narrative thread emerge here). And finally, we’ve got the South Australian made Mortal Kombat, which gave Perth director Simon McQuoid a fairly hefty project to tackle for his directorial debut, all the while utilising Australian crews as best as possible for all aspects of the production.

In a microcosm, you’d barely recognise these are being Australian ‘made’ films. Those inverted commas are important, because while the production crew behind the scenes might be Australian, and the financial support from the government makes a certain consistently wavering percentage of the film ‘Australian’, it’s hard to definitely call these Australian made films. In some ways, it feels bizarre to even call them American-Australian co-productions, given how muted the Australian-ness of the films can be. And, if we were to grab out the abacus and start moving beans around, we’d be sitting here all day long trying to figure out exactly what percentage of each production is actually Australian.

But, while I’m no mathematician, I can at least look at these three co-productions and glean simply from watching them how ‘Australian’ they are. What I’m particularly looking for is how distinct the Australian identity emerges throughout these films.

For Godzilla VS Kong, while the film itself is rather entertaining and enjoyable, and delivers impressively on its massive-scale destruction and big screen theatrics, it also struggles to showcase the Queensland outback for what it is. It’s hard to tell exactly which sequences were shot in Queensland, but I would hazard a guess and say that it would be the Skull Island sequences, which transplant the iconic rainforest of the Cairns region into a remote, mythical island. There’s something truly ‘otherworldly’ about the Daintree and its associated regions, and if you’ll allow me to unleash my inner-tree hugger for a moment, I do wish the Queensland government would recognise the strength of the environment they have for cinematic ventures, as opposed to continually clearing it for farmland or mining space.

Then we shift on to Love and Monsters, which also utilises the Queensland landscape to impressive effect, while also utilising the imagery of suburbia to highlight the destruction of what the ‘normal world’ looked like prior to the catastrophic event that brought the titular monsters to life. I want to focus on the imagery of Aussie suburbia momentarily, because while the numberplates have been changed, and people drive on different sides of the road, there’s a distinct difference to the housing of Australia as opposed to that of America. It’s hard to say exactly, but the tan bricked abodes and sea of lawns feels distinctly Australian. In a dystopian film like this, or even in Leigh Whannell’s masterful The Invisible Man, this not-quite-American familiar imagery helps add an off-kilter, askew feel to the world.

No doubt as more international productions find sanctuary and safety in the relatively Covid-safe Australia, we’ll see our suburban landscape be presented in different ways that hint at the Australiana of these productions. For Americans and other keen-eyed watchers, it’s easy to see when a production that is set in New York is filmed in Los Angeles, so naturally this kind of difference would become even more accentuated when the common place imagery of American suburbia is replaced by that of Australia’s varied houses.

Joining the lead character on his journey is an expressive canine called Boy, played by Kelpie mastermind duo Hero and Dodge, who had previously played another iconic Kelpie mastermind, Koko, in the excellent flick Koko: A Red Dog Story. I’m not sure how prevalent the kelpie breed is in America, but honestly, alongside the humble Blue Heeler, there’s no more iconically Aussie breed of dog than a Kelpie.

Outside of the bush setting, the canine representation, and the brief imagery of suburbia in Love and Monsters, there’s little else to suggest that this film was made in Australia as a whole, especially with precious few Aussie actors in the mix (tip of the hat to the always enjoyable Dan Ewing). Back in The Avocado Plantation, David Stratton mentions the appearance of Barry Otto and Todd Boyce in the Aussie based production of Dolph Lundgren’s The Punisher, saying, as if they were lucky enough to be in the same space as Hollywood royalty as the Russian boxer from Rocky IV:

Australians like Barry Otto and Todd Boyce were allowed to fill supporting roles.

The Avocado Plantation, David Stratton

So, if we extrapolate from that just a little bit more, then we come to the most Aussie production of the bunch: Mortal Kombat.

Yeah, look, I’m as surprised as you are that they actually gave the role of Kano to a true blue Aussie, given there’s precedent for non-Aussies trying to tackle the ‘Stralian accent (see Pacific Rim and Rough Night for appalling examples), but here we are, in the year 2021, with Oscar nominee Josh Lawson banging on as one heck of an obnoxious Aussie in this ultra-violent video game adaptation. Where Tom Hardy mumbled his way through Mad Max: Fury Road, somewhat muting the ocker personality of that flick, Josh Lawson slathers on the strine and embraces his inner evil-Steve Irwin with a proud kick to the crotch, making the most of his screen time and becoming one of the most memorable things about the film.

Lawson is joined by fellow Aussies Jessica McNamee as Sonya Blade, Angus Sampson as Goro, Damon Herriman as Kabal, with cameos from David Field and Kris McQuade helping bulk up the Aussie actor quota. While the diversity of talent is on full display in Mortal Kombat, the Aussie accent cuts through like a knife, ensuring that the brutal colloquialisms stick in the viewers mind powerfully. If we were to focus on the global awareness of Australian culture (represented here as a misogynistic Aussie bloke dialled up 200% to the point of absurdity), then Mortal Kombat takes the cake with a solid chunk of Australiana given screen time.

Good-o for dogs then.

Yet, Mortal Kombat is the exception, and not the norm, and while it’s great to sit down and watch a Hollywood blockbuster and feel a little bit seen, it’s becoming a rarity, and will likely continue to do so going forward. Sure, Thor: Ragnarok had a wealth of Australian imagery in the mix, with Valkyrie’s spaceship being called ‘the Commodore’ and painted in the colours of the Aboriginal flag, but these are peripheral tokens that, if taken away from the film itself, would not effectively ‘harm’ the final product.

And that’s what we’re dealing with here: products.

American cinema and television is one of the grandest products around. It’s easily exportable, transferrable across the globe, becoming the dominant force. Where we once rose up in anger at the Americanisation of Arnotts biscuits, Aeroplane Jelly, the staple Aussie food that is Vegemite, and even brands of matches, the Australian public carries an air of indifference when it comes to the Americanisation of Australian film and television culture. We, like Canadian audiences, have found ourselves wrapped up in a cultural cringe when it comes to Australian film and television.

This is not to say there aren’t exceptions to the rule, with Robert Connolly’s masterful The Dry and the family friendly Penguin Bloom showing that there is still an audience for a certain type of Australian cinema, but the dominant feeling about Australian films is that Australian audiences simply aren’t interested in them. We recoil when a kitchen sink drama appears, and shudder at the notion that anyone would ever decide to make an Aussie comedy after The Castle (now almost 25 years old). Audiences still hold onto the rose-tinted notion that the hey-day of Australian film came with Muriel’s Wedding and Priscilla.

And yet, as Australia enters a Covid world relatively safely, with two week staycations in quarantine hotels for the unfortunate, and quarantine hubs on farms for the wealthy, we’re becoming a sanctuary for Hollywood to make films in the relative safety of a world without masks. For the foreseeable future, Marvel will uproot all of their film productions to Australia, moving away from the hub in Atlanta, Georgia, and now turning Sydney into San Francisco and beyond with their upcoming slate of films. Maybe as a duty of service to Australia, Marvel should finally introduce the Aussie hero Manifold into the mix.

It’s not just Marvel calling Australia home, with countless other Hollywood productions shifting location here, including Melissa McCarthy and husband Ben Falcone making Sydney their home-away-from-home, Liam Neeson in Canberra doing yet another action flick, and Nicole Kidman and her entourage filming the Nine Perfect Strangers TV series here. Sure, there’s another Mad Max-associated film, Furiosa, coming along, this time actually filmed in Australia, but the slate of Aussie-focused Hollywood fare is slight, and with production crews being swallowed up by Hollywood productions, it’s hard to see how Australian films and shows will emerge safely and securely from this sea of seppos.

Additionally, with a government that is potentially scarpering any chance of local post-production crews being utilised on Hollywood productions by raising the minimum expenditure threshold to $1 million, as opposed to the current threshold of $500,000, we may see a drought of post-production crews being able to actively be supported by an imported industry at large. This is a pointed issue given how both state and federal governments continually champion the work opportunities for local industries, and how it will give them exposure to working on larger productions. There’s an air of ‘payment in exposure’ here to the kind of announcements that are happening with greater frequency than usual, almost as if local production teams should be grateful that each government is working to ensure their job security.

Yet, closer to home for this writer, for all the bleating and baaing from the state government about a proposed studio being built smack bang in the middle of Freo harbour (a working harbour at that), there’s been precious little interest or investment in assisting locals in getting a foot into the film industry itself. If we’re landing in such a fertile ground of Hollywood film production in Australia, then where’s the splash back for the next FTI which will help foster the next generation of Aussie production designers, editors, visual effects artists, and more?

This leads us to the crossroads and the crux of the identity crisis that is looming over the Australian film industry:

Will the practitioners, artists, creatives, and production crews across Australia become rent-a-crowd workers for the factory line of Marvel and DC films that’ll be made in Sydney, Melbourne, and the Gold Coast going forward? And, in the process of doing so, will the Australian cultural identity start to fade away into the miasma of digital trickery that is swallowing up film movements around the world?

Or, will the Australian government allow the Australian film industry to embrace this moment and encourage the growth and provide fertile ground for Australian stories to be told?

It’s quite clear that the former is likely to take place, with the entirety of Australia becoming the Vancouver of the Southern Hemisphere.

The Australian film industry has long championed and fought for the Australian cultural identity on screen, and yet, because of how our film industry is set up, with so many films relying solely on government grants and support, it’s going to be harder to establish these Australian stories, and to maintain a wider, global audience appeal.

To be clear, the Canadian film industry continues and thrives, supporting Canadian stories and filmmakers, and embracing new waves of Canadian cinema. It’s just stifled and smothered like so many other film movements around the globe by the unceasing, ever-pumping, enduring Hollywood fare that filters onto our screens. While Canadians and Australians alike are employed en masse to help bring these films to life, it occurs at the cost of their countries cultural identities.

It’s not as if there isn’t an audience for Australian films, with fare like Lion, Hacksaw Ridge,and Mad Max: Fury Road receiving Best Picture nominations (even if Hacksaw Ridge is an American story made in Australia), and Jennifer Kent’s masterpiece, The Babadook, shaking the international horror community to its core. Additionally, Shannon Murphy’s debut feature, Babyteeth, hit the right audience at the right time, becoming an underground success with fans around the globe.

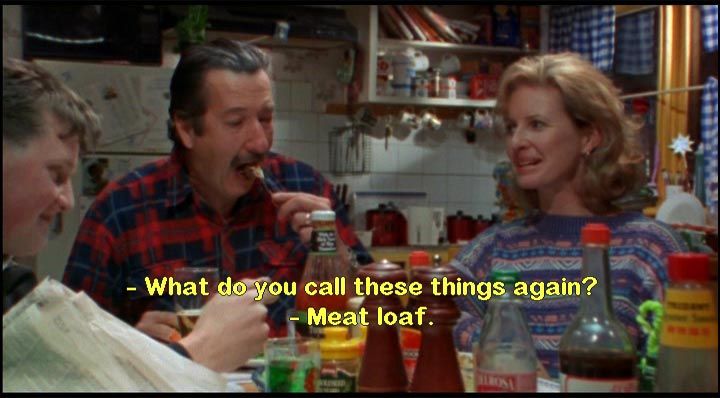

But as we’re seeing with films like Peter Rabbit or The Invisible Man, the ‘Australian’ identity simply isn’t there. It’s got the cast, it’s got the crew, they’ve got the directors, but otherwise, the rissoles have been turned into meat loafs, and Mel Gibson’s been dubbed by a yank.

It’s not all doom and gloom though, as we look towards the horror community to find the dedication and affection the global gorehounds have for the macabre, and see the support for horror and exploitation films in Canada with the likes of Hobo with a Shotgun, The Void, and Pyewacket, all adding to the burgeoning and thriving horror genre in the decade. In Australia, The Babadook, Relic, Little Monsters, and Lake Mungo, all gained global audiences who lapped up the outback frights with utter delight.

On the back of The Babadook’s success, Jennifer Kent effectively established herself as one of the most vital and important directors of this generation, making each subsequent film she will make appointment viewing. This helped immensely when it came to promoting her follow-up film, The Nightingale, an excoriating and furious rape-revenge thriller that pulled no punches and demanded viewers witness the horrors and brutality of colonialism in Australia. It’s a devastating film to endure, and if this were Kent’s first film, it likely would have demolished any chance of an audience attending her second.

By sequestering a countries cultural identity into a genre that mainstream audiences rarely venture into unless they feel it’s safe enough, might help provide it with some kind of bizarre oasis of safety. Within the horror community, cultural identities remain safe and widely accepted, with the otherwise shunned affectations of a culture being allowed to grow freely within its terror-inducing boundaries.

This is cherry-picking an example, but it’s an apt one to highlight how easily it is for a countries cultural identity to become a niche enterprise for the country alone to appreciate and enjoy. Australian culture can be great, and can be a wonderful thing to share with the world, so why shouldn’t the Australian government embrace who we are and champion Australian stories? Instead, the outward appearances seems to be open season for Hollywood to use and abuse our film industry as it pleases because ‘this playground is safe’.

It’s even more frustrating and devastating as we’re witnessing the emergence of a decade long creative streak from the Indigenous New Wave within Australia, with filmmakers like Warwick Thornton, Rachel Perkins, Wayne Blair, Ivan Sen, and Leah Purcell, all creating work that is redefining what Australian cinema is and should be. I stand by the fact that Sweet Country, Top End Wedding, Jasper Jones, and the Mystery Road series, are all top tier film and television work that should be embraced around the globe.

Ultimately, our culture and society is reflected in the films and entertainment that we make, and if we’re not able to tell our own stories, then we become mere parrots to the American film industry, imitating a lifestyle and culture that is distinctly different from our own.

While it’s easy to champion how Australian Mortal Kombat is and feels at times, it’s also a Hollywood production that never truly embodies Australian culture. I’m happy and glad that South Australian creatives got to make one heck of a bloody, effects heavy film, and I’m stoked that it’s a success too. Hopefully they get to hit for six for a sequel. But additionally, I hope that Warner Bros. and Marvel take a look at what we’ve got here and utilise our culture for their own stories. A bit of give and take.

Australian cinema like Sweet Country, The Babadook, Mad Max, My Brilliant Career, Top End Wedding, Chopper, The Dry, It All Started with a Stale Sandwich, and The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, are our Vegemite, our Tim Tams, our AFL. They flood through our veins and fill our guts like an ice cold tinny on a scorcher of a day. They are in the air we breathe like the hazy smell of distant smoke during a prescribed burn off. They are a sunset on Cottesloe beach with your feet in the sand, salt water spattering your face. They are distinctly Australian. This is what we’re fighting for. We cannot lose this.

I want to leave you with a version of the question I opened this piece with, and for you to take this question to everyone you talk to film about:

What was the last Australian film that you watched that wasn’t one of the fifteen rotating titles that always comes up in discussion? And who are the Australian directors that best explore Australian culture on screen?

[1] A sly nod to Thomas Andersen’s influential and impactful video essay Los Angeles Plays Itself.