As I reflect on 2023, my path through this difficult year has been tinged with the continuous destruction of the Australian ecosystem. As I’ve travelled across my home state of Western Australia, I’ve witnessed the pulping of trees that I had grown to know across my four decades in this world. Instead of a peaceful awakening each day, I’ve grown to accept that the whir of a chainsaw at 7am is how my day will begin.

Humanities dominant relationship with nature is seemingly at odds with the critical space we find ourselves in. We live in a world that is perpetually shouting about the impact of global warming as our capitalist society demands an unsustainable growth that appears to be hastening our demise. That’s an unshakeable, devastating feeling, yet it’s one that I found was given a mild salvation in the guise of Laurence Billiet and Rachel Antony’s empathetic and tender documentary The Giants.

I wrote about the notion of nature in the arts and the trees we have lost at the close of the 2023 Perth Festival where The Giants launched. It screened under the mammoth and inviting pines of the Somerville auditorium, a perfect place for a film about some of Australia’s great trees and one of the pivotal figures who has helped secure their future: Bob Brown. That screening is an event that I will not soon forget, and it’s one that I carry in my mind with a vitality and vibrancy that precious few memories have.

My heart has wrapped around the story that Laurence and Rachel tell with The Giants, and in following the films Instagram account, I’ve been able to see their journey across Australia as they’ve toured with the film, meeting audiences who must have surely had similar experiences with the film. It’s that thought that kicks off my conversation with two of the kindest and most considerate filmmakers I’ve had the honour of talking to. Across the below interview, Laurence and Rachel talk about their relationship with the trees they documented and the manner that their own film managed to radicalise them, while also talking about the importance of reflecting the spirit of their subject in the form of their film.

The Giants is now available to view on DocPlay where it can be watched alongside an exclusive interview between Bob Brown, Laurence, Rachel, and host Jo Lauder at the Astor Theatre in Melbourne. To book a screening of the film, or to find out more about what you can do to help save our forests, visit TheGiantsFilm.com.

This interview has been edited for clarity purposes.

I’ve loved seeing your journey on Instagram where you talk about the interactions that you’ve had with audiences. It must be such an exciting experience for you both.

Laurence Billiet: Sometimes you put a film out and it shows and then it’s over. What’s been wonderful with this film is that we had the festival run and then we had the cinema run, and at every single stage we’ve been able to engage with a whole community of people who took the film in their stride and made it their own. It’s been a wonderful personal journey as well. It’s been great for the film, but also for us personally to meet people all around the country who have watched the film and think, “That speaks to me, I can do something with this. I can make a difference. I’m going to organise a screening.”

Rachel Antony: Obviously it strikes a chord with the environmentalists, particularly forest lovers, but it’s interesting because it has been used to rally communities around all sorts of things like fighting coal in Newcastle and fracking in the Northern Territory. It’s been interesting to see that people have leapt on it, not just in cities, but in places like Taree or Orange in NSW or Penguin in Tasmania or in obscure places I’ve never heard of.

We took the film to Parliament House in Canberra and we had a screening in the theatre hosted by Sarah Hanson-Young. Everyone in the building was invited, and we would have loved to have all of the MPs and so on there, but it’s always very frantic in there. We did find there were some MPs that did make some time to come along, which is fantastic. This all lead into the Rally for Native Forests. We just feel like we’re gathering momentum, and the film has a life of its own and now it’s creating things that we couldn’t have anticipated.

LB: It’s really energised everyone. We’ve been able to bring the issue of native forest logging, which had been somehow forgotten, back on the agenda and everybody’s rallying behind it. Victoria changed the law regarding logging[1], following suit after WA started last year[2]. Now we’re hounding the New South Wales government to try to get a win there. Tasmania will be last, but if we could get a win in New South Wales it would be wonderful because that’s where the action is at the moment where there’s so many amazing forests being destroyed right now. It’s hard to believe, isn’t it? It’s such a wealthy state.

RA: The Koala national park is being logged[3] before it’s given to koalas. Where are they supposed to live? I just don’t know. It’s just confusing.

LB: It’s like if you were writing an episode of Utopia. It’s exactly what’s going on. It’s very cynical. We feel like the film has joined forces with an existing movement and it has kind of re-energised everyone. Rachel and I have felt like we just need to give this a go. We could just close the book and move on to a new film, but we felt like this is what it’s all about. We’ve done a lot of work the last few months to hand hold the whole thing, and it’s been really rewarding.

The film is both a reflective piece and also looks forward piece. As you’re talking about the experience of sharing it and the rallying action that’s taking place with that, I’m curious whether you anticipated that it might have this kind of reaction when you started?

LB: It certainly was our intention to create something that might make people think, ‘I want to be part [of change.’ The genesis of the film was from our experience of the fires that took place all over the country in 2019. We were very deeply distressed by them and felt powerless. Then the logging trucks showed up a couple of weeks later for salvage logging, but not only that, then the logging intensified, because they’d lost state forest to fires. The forest that hadn’t been burned was exposed to even greater logging because they had to make up what they’d lost in fires. It’s the absurdity of it all.

It made us very angry, and we felt we had to do something. At the time we were thinking, ‘What can we do?’ We thought we do know about film, so we can make a film. That’s how it sort of started. Really, our intention was to get people to discover the beauty and the magic and the wonder of the forest and try to find a new cinematic language to do that because forests are very hard to film. It’s hard to engage with forests because you’re on the ground floor and you don’t really see what’s going on with the richness and the diversity of everything that’s going on in forests which you can’t see happening [within] the trunk [of the tree]. So we were creatively interested in finding a way to bring that to the screen and hopefully move people to get them to want to do something about it.

RA: People are quite familiar with the David Attenborough School of documentary with it’s beautiful, hyper realistic imagery of the natural world, but we wanted to surprise people a bit. We felt that one way of doing that is almost to just trigger the imagination. We wanted to present those trees and those forces characters within themselves and just speak to that almost childhood connection that we have to nature that we forget so very quickly. That was the idea behind the animation and also the aesthetic treatments of the cinematography as well.

LB: What we did is we had three trees that were characters that we chose for their specificities and characteristics. Our eucalyptus Regnan are some of the tallest trees in the world, the Huon Pine’s are some of the oldest, and the Myrtle Beech in the Tarkine for the richness of its ecosystem. So we cast those three trees, and then we scanned them and then we worked with an animator, Alex Le Guillou in France, who has developed a passion for working on point cloud animation scans of a forest nearby his house.

We collaborated with him to create what we call ‘forest scapes.’ They’re quite factually correct because they’re based on actual scan data, but they’re animated in a way that opens the imagination and reveals in a visual way what you might not be able to see whether it’s the flow of information in what goes on between trees and the exchange of nutrients and whatnot. We wanted to do something that had the power to unlock people’s imagination.

We’ve lost so many trees in the suburb that I’ve grown up in for the past 30 years. These massive trees that I’ve seen grow up and they’re tearing them down. The suburb is now a sea of houses. Getting to see that communication method that the trees have is vitally important. They don’t just cool our suburbs and provide oxygen. They’re homes for birds and insects, and they communicate with one another, so getting to see that visualisation has changed how I see how the society that we live in. I’ve got a lovely native garden which now feels like an anomaly in a sea of nothing.

RA: What we’re seeing is firstly native logging, and secondly the clearing of woodlands either for mining or for development. There’s so much degraded and cleared land in this country, it just simply doesn’t make any sense to remove these trees. In suburbia, we’re seeing a loss of canopy and this is why we’ve reached this point of a climate crisis. We have never needed trees more for all the things that they bring to us, from cooling to securing water cycles, and yet people seem to value them less and less and just build bigger houses with more concrete. If we want to make our cities cooler, it’s quite simple: we firstly plant trees, but secondly, look after the ones we already have because it takes time grow a tree.

We’re talking about trees, but the other giant in the story is, of course, Bob Brown. When did his story fold into the mix?

LB: From perhaps from the word go. We’d been reading a lot of books about trees that inspired us like The Secret Life of Trees by Colin Tudge, The City of Trees by Sophie Cunningham, and The Overstory by Richard Powers. We’d been thinking about trees and forests and the story that trees are a community, and that we are only just discovering that, which I think is gobsmacking. It says a lot about good science that we’re only cottoning on to that.

Then we were thinking about Australian icons and in the creative process the two things merged in our heads. We thought it’d be really interesting to tell the story of Bob’s life intertwined with the story of the forest and explore the overlapping connections between human life and tree life.

RA: That’s sort of what got Bob involved. We assume Bob’s had a lot of propositions over the years to make films about his life, but Bob genuinely is not that interested in making a film about his life unless it actually does something. He is an activist first and foremost. When we pitched this to him, he said, “I’ll do it for the trees.” It’s interesting, because as the film starts, those connections might seem more in parallel between the forest and Bob, but I think by the end of the film, the way that you start to look at the trees, you start to absorb his own mindset and the way he views the world, and suddenly it all comes together in a way that’s really quite beautiful. I think it is a worthy tribute to Bob Brown who’s done so much for the environment and is such a powerful figure.

One of the things we were interested in is that he’s an elder, so to speak. We thought he might have the ability to speak across generations, because his concerns are so contemporary. He’s of an older generation and we wanted to find someone who could somehow link those things together. A lot of the talk about the climate crisis is very much pitched to the younger generation who are going to have to clean up the mess of the older generation who have had everything and are doing nothing. We thought, we need to work together on this, and Bob Brown was an interesting person to do that.

We knew, but we didn’t fully realise, that it was going to be such a great story. We also didn’t realise how hard it was going to be to intertwine these two things. Bob Brown’s story alone could fill a miniseries, so we had to be really brutal. We spent a lot of time – probably the last six months of production – just trying to cut away the minutes and seconds to reduce it to something that’s closer to a commercial film release. In retrospect, we were very optimistic about that. It is a bit of a long film, but in the end, we couldn’t cut anything more away.

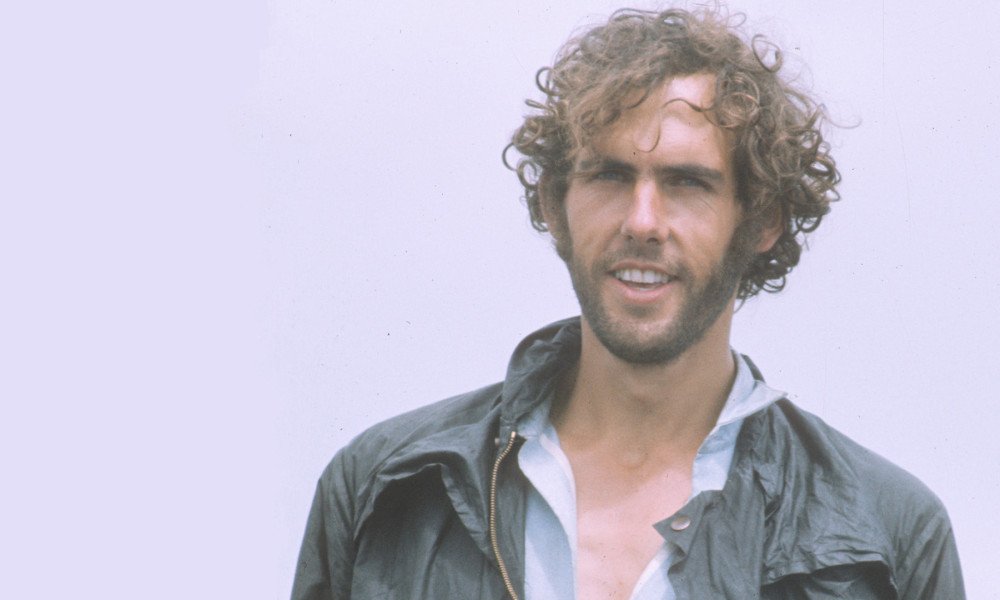

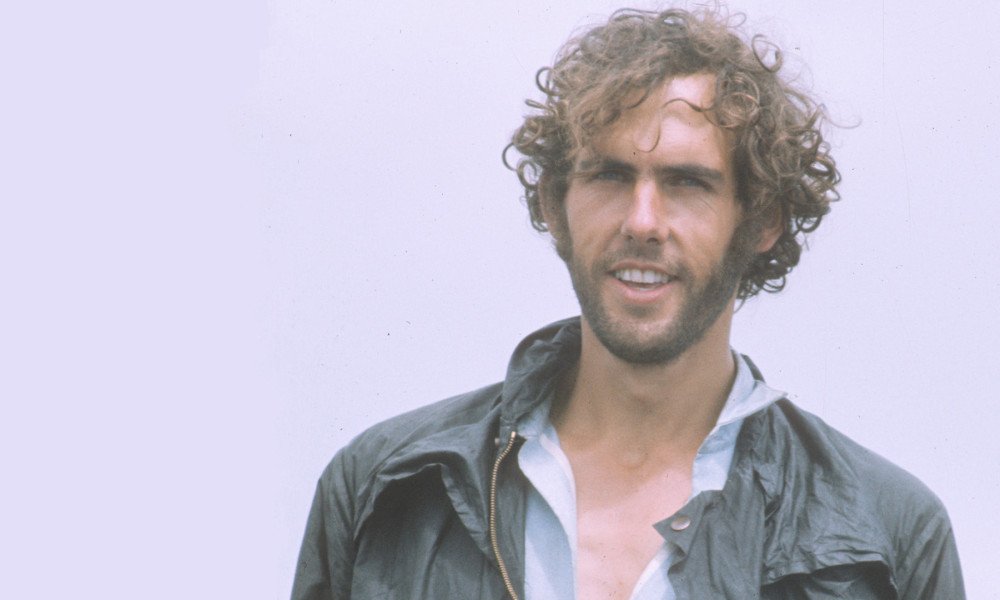

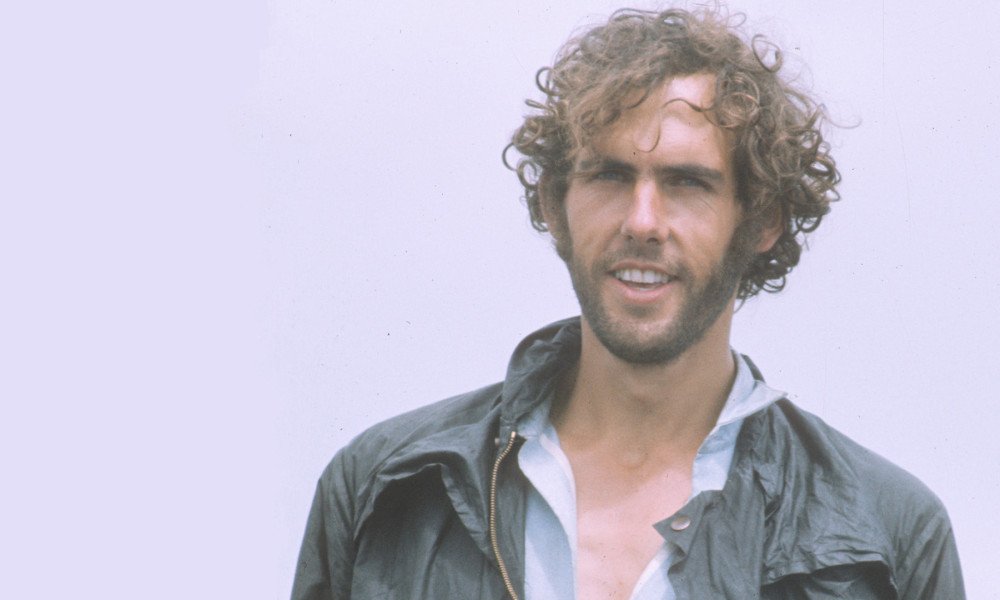

LB: I feel like we got the hecticness and the intensity of his life. We’ve spent a lot of time with him recently, we have probably spent a lot more time after the film was released than during the film production with him. He’s so extremely busy. He’s extraordinary. He’s up all the time doing stuff. He’s still as committed now at the age of 78 as he was in his early 30s, when he shows up on screen, so it’s inspiring.

The Giants is not a distinctly political film. Even though it does have the strain of being an activist film, it’s not a film that has an outward agenda. How do you balance that semi-apolitical tone while also maintaining an activist message but not making it feel like it’s pushing an activist message?

LB: I think that a lot of it is about trying not to do what’s predictable. I think when you make a film about Bob Brown or about the forest, it’s almost like you can see it in your head, right? Do you want to go watch it? No. We’re quite interested in making films that keep ourselves entertained and people on their toes. In Freeman we mixed contemporary dance with the story of Cathy Freeman, which was unexpected. Some people were worried that it would not go down well in the mainstream, but it did and the audience loved it. The audience shouldn’t be underestimated. People love to put two and two together, and not be told what they need to think. That’s kind of our approach, which is ideally that people put two and two together themselves and come to their own conclusion. I think if you try to tell people what they should think and you embed that in the narrative of the film, then it’s passive, and it’s not actually as effective as somehow putting the facts together in a way that people can then form their own conclusion. And that’s what we’ve tried to do.

RA: On the political stuff, some people think of Bob Brown is a primarily as a Greens politician because they’re aware of him at a point in time, but we treated him more like an activist. His politics is part of that longer life. We were quite conscious of not wanting to make some sort of propaganda film for any particular party which would exclude people. It just wasn’t appealing and it’s not actually what we think the solution is in any case.

LB: Bob is a very positive and inclusive person. I know that perhaps some people [perceive] the Greens as divisive, and Bob himself has been portrayed like that by the media and others. But as a person, he is a very unifying force. He’s gone around and met people all over the country, and you cannot find someone who doesn’t like the man. He is a lovely person, a loving person, and an extremely open person. I think it’s important that when you make a film about somebody that the film channels the spirit of the person. We tried to feed off his vibe and the way he looks at things. He’s someone who’s always looking forward. He loves everyone and he is interested in everybody. He treats everybody with the same respect and we tried to channel that spirit.

We’ve had some feedback from people who have seen the film, and from people that have quite conservative, alt-right backgrounds who went to see the film and loved it. Bob has very conservative values, ultimately, from his religious upbringing. They’re very common-sense values. He’s a very decent person. They really responded to what he did and why he did it in that David versus Goliath way and taking on the man and standing up for people. I think people really responded to that, regardless of the political allegiance. It’s been interesting because we were wondering whether that would be the case, whether people who don’t like the Greens would like the film and the feedback has been that it has really worked for everybody.

RA: Some people did say nice things about Bob, but we made the conscious decision to not include that in the film. We didn’t want it to be a whole bunch of people talking about how great he is. It’s not interesting creatively, and it’s not putting you in his mindset. We didn’t want talking heads. That’s also why we didn’t have talking heads with anyone really. I want to hear scientist give me insights about the eucalyptus Regnan, I don’t want to look at that person’s face and decide if I like them based on what they’re wearing or any of those things. I just want to zero right in on the material.

LB: The point of view of the film is from Bob, so it’s not a commentary on him, even though obviously there’s a lot of participants, but it’s a first-person account in some ways. That cuts through some of the issues that you raised around making it a puff piece or making it something that is perceived as being a propaganda tool, because it’s not; it’s an actual personal, emotional story.

You mentioned casting the trees earlier, how did you decide on which trees to include?

LB: We thought we’d like to talk about the ‘giants’, and what those trees are. The eucalyptus Regnan is this iconic Australian tree, which is a gum tree predominantly found in Tasmania and Victoria, and these are trees that are 80-100 metres tall. They’re amongst the tallest trees, on par with the redwood, but not celebrated that way, because we chop them up and make toilet paper out of them, which obviously we would be scandalised if the Americans were doing that with their redwood.

We collaborated with a number of people in Tassie, particularly an outfit called The Tree Projects[4], a husband-and-wife team who are scientists and climbers and who climb giant trees and educate people about them. We went on recce and they took us around to some of the trees that might be suitable. There’s a whole bunch of consideration not just from the aesthetic appeal of the tree, but also how we were going to be able to film them. We had this vision that we wanted to take people into the trees and provide a slightly different viewpoint that you might not have had on the trees.

Beyond the scanning that we did and the animation, we also did some pretty amazing filming with Sherwin Akbarzadeh, the DOP in Melbourne that we worked with. We did a lot of cable cams through the canopy; not only horizontal cable cams, but also vertical ones, which are a lot more difficult to achieve up those trees. That’s the opening shot. We went and found those three trees. One eucalyptus Regnan, the tallest tree, a Huon Pine, the oldest tree in the Tarkine, and one that’s currently under a lot of threat, and a Myrtle Beech which has this beautiful and extremely rich and diverse ecosystem with lichen up there.

RA: They also had to be close enough to the road to carry all the stuff in.

LB: They all had a bit of a story as well. The Myrtle, for example, is the first tree at the end of a logging track that the Bob Brown Foundation stopped builders going forward. They managed through a few weeks of action to stop the logging in that area. The tree that we filmed in the Tarkine is the first tree that stands at the end of the logging line. It’s a beautiful tree but one that also quite poignant.

We spent a few days at the foot of each tree filming. Our sequences were quite choreographed, we didn’t just go and point our camera around. We had quite a clear idea about what we needed to get to storyboard the sequences in the forest. We went in there and got the shots. We spent about three days per tree so we had this really lovely bond because it’s a long time to spend with a tree. You get a really good sense of the energy and what goes on, particularly the Huon Pines, you really feel that they are thousands of years old and you are just so insignificant compared to them. It’s so humbling.

For the Regnan, we did a vertical line up to the top of it. That was an actual cable cam and not a drone, and it was important for us to do it because we wanted to get the atmosphere of the shot. It’s funny how technology is one of those things that even though you can feel that it’s a drone shot, it has a different vibe. We were able to film with beautiful camera but it ends because we couldn’t film with the cable cam for the last five or ten metres, hence why we transitioned to the scan, and then up to the drone. Interestingly, we added that drone shot at the last minute because we felt like even though we never wanted to have people in our forest world, there was something about the scale of it which didn’t quite land until you put a person next to that tree. That’s the Tree Projects people rigging our tree. That really gives you a sense of what you’re looking at and how massive those trees are.

You’re talking about having a bond with the trees. I’m curious if you can talk about how, through the shooting process and even in post release, your bond with nature and with Bob has changed and evolved?

LB: One of the aspects of the story of Bob that attracted us is his relationship with Paul. That entire story is perceived as a bit of a subplot, because his main activity has been about the environment. Rachel and I are a same sex couple as well, so for us, that was something that was quite important to be able to tell that story in a way that we felt was dignified and profound. What Bob did was extraordinary.

Also, Paul is an activist in his own right, he’s done some wonderful things in Tasmania. We felt like we wanted to present this story in a way that was poignant and beautiful and moving, and we got to do that. It’s a beautiful love story. I think that we’ve created a bond with both Paul and Bob. Paul is very pleased with the film because he’s Bob’s number one fan.

RA: We knew he would be our number one critic, but we needed to get him on board. He’s not someone you can hoodwink; he will come to his own decision. You just have to cross your fingers. They’re both very happy with the film. I think partly that’s because of the acknowledgement of their relationship as the love story, and also Paul’s role, who, in any other circumstance would be the star of the show.

What has been interesting is since the launch, we’ve spent more time with them subsequently because we’ve done the tours, and we’re always in contact with them. I think we’ve really realised as well – which is funny to come to this conclusion right now – about how hardworking they are. They’re really old school, baby boomer, hard-working people. They don’t have a day off, they don’t sleep in. They get up at four o’clock in the morning, they drive off to the airport, they get on the plane, they go. It is nonstop. We can’t keep up with them.

LB: It’s like a love child in the sense that you create something together, because, in a way, there’s so much trust. I always admire when people say yes to something like that, because frankly, it’s crazy, right? You put so much trust into strangers. We didn’t know Bob. Rachel conducted the interviews with him on Zoom because we were in lockdown.

RA: We were always in lockdown because we’re in Melbourne. We wanted to do them in person, and in the end, we had to get started. Fortunately, Bob is such a professional person and was ready do it all online.

LB: He comes with his A-game. Everybody was collaborating with the best intention. They were surprised by the film, perhaps they didn’t really expect it as well, because it’s perhaps not what you expect. I think it seduced them. I think more importantly, Bob has been participating in a lot of the screenings and is seeing the profound impact it’s having on people. The best thing about it is that it’s people of all ages, you get teenagers or even younger kids completely get getting it. We’ve seen elderly people, 100 years old, coming to screenings, loving it and feeling inspired by it. For Bob and Paul, it’s exciting to see the impact it’s having on people. We share that together. We worked together on this, and we continue to work with them. Hopefully, we’ll keep winning some more battles, and beyond Victoria, the film will have even more impact, and then we can celebrate.

RA: In terms of our relationship with the environment, the forest, there’s a sense of responsibility there, which can be quite burdensome because you feel like you can’t give up. We’re not activists. I’ve come to respect activists so much more, they’re the marathon runners, because they know that they have to pace themselves because it could be decades of fighting, and a lot of them have been fighting for decades. We are slightly different kinds of people who are going to make something and then everything changes because it seems logical. It’s an interesting process to go through that and support them and then to find our rhythm. You don’t know how long this race is going to go. Native forest logging should stop tomorrow. We don’t know what the holdup is. Until then, we need to keep going.

LB: We’ve been radicalised by our own film.

RA: We’re just like everyone else. We’ve learnt a lot about forests. We gobsmacked by how priceless they are and we’re just horrified about we’ve been doing with them. It’s just absolutely senseless.

The Giants continues to come up in conversations that I have with people as a film that people have seen and have been encouraged to enact some kind of change in their life.

LB: We hear people say things that are extraordinary. People say to us, “You have no idea the impact it’s had on my life.” That’s a big statement to make and people make those statements a lot. It makes people reassess a lot of things. That’s the thing about film, once you open that door and if you can be in that place with people, it’s such a wonderful thing. That’s what it’s all about in a way, to change the inside of somebody, to make something click or shift ever so slightly so their perspectives change. I feel the film has done that. We are very pleased that Bob’s life has been a tool for that. That’s also what it’s all about for Bob.

Ultimately, he is an extremely private person, and he’s used his life as a vehicle for change. He’s put himself out there, whether it’s on the Franklin rafting down the river, or as a politician when he came out. He has used his body and his life as a tool. It’s not about himself. It’s not about him coming out. It’s about what this action does for others. I think if a film is going to be made about him that the film also works in that exact same way.

RA: Ultimately, people are emotional species. We all know the facts about climate change. We know what deforestation means. But it’s when you feel it, that you go, “Oh, yes.” It’s not cerebral, in a sense. It’s a physical knowledge. Film doesn’t just speak to your head, it speaks to your heart. That’s what gets people. What sets the blood pumping is that wonderous beauty of the forest.

LB: An important thing for us as a starting point was to focus on the beauty of the forest. We can’t watch environmental films because we find them too depressing. We really didn’t want to fall into that trap that you’re going to watch an hour and a half of clear felling and feel terrible and anxious about that. Our starting point was the opposite, which is to celebrate the beauty of the forest, the wonder of the forest, and make people fall in love with it, and to make people fall in love with Bob Brown, and then from that comes caring.

It’s two thirds of the way into the film that we bring out our first clear felling shot. We felt like we couldn’t bring it any sooner. When we worked on the trailer, we had to cut where they had clear felling there, and we were like, “No, no, no.” Those images are very off putting. There’s the reality of what’s going on, but it’s something that you need to come to. We really wanted to create a space for people to revel in the magic of the Australian landscape before we talk about the bad news. It’s managing people and your own emotions, and to try to do that in a way that’s uplifting and hopeful and exciting as opposed to depressing and anxiety generating.

I want to touch on one last thing, which is the aspect of trust. You’re talking about building trust with Bob via Zoom, which can bring its own problems, but you create shorthands to do that. I’m curious about how trust factors into the way that you both work as co-directors and as storytellers sharing Bob’s story and being vessels to usher his story into the world. How important is trust and how do you build on that as filmmakers?

LB: I think that one of the important things is to be true to yourself to start with. We’ve been helped by having on some of our films quite a clear idea of what we want to do from the outset. Even though it’s very clear what it is, in practice, it’s important to have a clear idea of what the intention is and what the spirit of it is, and then stick to that. It’s a really great way to rally people because filmmaking is teamwork. Obviously, there’s two of us, but there’s dozens more people involved in the creative process. Our job is to somehow dream something up and get people to see it in their head and then contribute and work towards that.

I think that that truth of the original idea, the concept, or whatever you call it, the vision, the dream, that’s something that I think we found helpful in carrying that through. For us, the how is as important as the what. If you treat really people really badly and you’re disrespectful to the values that you think the film’s about, it shows in the film. It’s one of those invisible things, but if the process of making the film has been horrible, often it translates somehow on screen.

So for us, how we make the film is just as important. We work with a lot of female and Indigenous creatives when we can and try to do it in a way that’s fun and pleasant and positive and that we have a good time because making film is a nightmare. It just goes wrong the whole time. Sometimes it’s an exercise in things go wrong. It’s so important that you’ve got to try to keep to that. From that comes a lot of trust, because if you try to behave that way, people will connect with that. We’ve worked with really wonderful people and have positive experience working with them, and everybody’s really happy with the end result. For me, that’s what trust is about in the whole process: be truthful to yourself.

RA: Certainly with interviewees, people didn’t know who we were. We did a lot of interviews remotely. I don’t think Christine Milne had a lot of faith in us, but she was very pleased with it in the end, because a lot of people have been burned by various media outlets and so on. Listening to what people have to say and to not have a pre-set agenda [is important]. As a scientist, you need certain kinds of information, but that’s not an agenda, that’s just filling in gaps of what I need to show. We let people speak and then we just took the bits that projected the story forwards the best. It was wonderful. We spoke to so many amazing people in the course of this film, and they’re all fabulous in their own right.

LB: It’s a big leap of faith for a lot of people to do that. We always tried to think ‘if I was listening to myself being interviewed.’ You use so little of what’s being said, so you’ve got to be true to the spirit of that person and what they wanted to say and convey.

With Bob, it’s very important that the subject of the film is also not only happy with the film but recognise themselves in the film. When we did Freeman, Cathy felt that truly reflected her experience. Bob had hardly any comments whatsoever, we had to tease that out of him. It was important that he felt that the film was representative of what he is about, rather than to do something that’s exploitative. As a filmmaker you know you can cut anything you want out of what people say, and you can make them say the opposite of what they meant. So, it’s important to respect people. People give you a lot of time when you make a documentary, no one’s paid, people do those interviews out of their own goodwill, so you’ve got to make sure that they’re happy with the end result.

[1] https://www.deeca.vic.gov.au/futureforests/immediate-protection-areas/victorian-forestry-plan

[2] https://www.wa.gov.au/organisation/department-of-jobs-tourism-science-and-innovation/native-forest-transition

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/aug/12/nsw-labor-accused-of-fundamental-breach-of-trust-over-logging-in-promised-koala-national-park

[4] https://www.thetreeprojects.com/