Not since the slap-in-the-face arrival of Justin Kurzel with Snowtown has there been an Australian filmmaker who has presented violence on film so viscerally like Thomas M. Wright.

I say this knowing that both of his feature films contain precious little violent acts. The nerve shredding Acute Misfortune told the story of artist Adam Cullen (played with a possessed performance by Daniel Henshall) and the youthful biographer (Toby Wallace’s shattered Erik Jensen) who tried to pull Cullen’s truth out of his chaotic life and put it down on paper. All of which presents a fractured experience that is likely to cause a panic attack or two, so stifling is the tension.

With his second film The Stranger, Thomas M. Wright examines a real-life tragedy through the perspective of the undercover police officer (Joel Edgerton’s Mark) who works to ensnare Sean Harris’ Henry Teague within a manufactured crime syndicate that exists solely to bring him down. The violent act that Henry has been alleged of is rarely mentioned in the film with Wright allowing the echoes of trauma to reflect through the narrative until the soul-crushing conclusion.

The act of violence is pointedly absent from The Stranger but is so profoundly felt in the tools of filmmaking. Simon Njoo’s editing acts like paper cuts in the webbing of your fingers – precise, painful, and horrifying to imagine. Sam Chiplin’s cinematography embraces the characters in darkness to the point where you start to question if light has ever graced this world. Andy Wright’s sound design reminds you constantly of the artifice of the relationship between Mark and Henry. What initially sounds like the flutter of moths wings sputtering on the soundscape is in fact a bullroarer, a war sound.

The Stranger is a meticulous, powerful film. It is also one that plays as another entry in the ever-growing library of Australian films that attempt to reconcile with the violence, trauma and resulting tragedy that has occurred on this broken land. For some viewers, this almost obsessive quality that some Australian filmmakers have with the acts of murderers is too much, creating a pall that hangs over the rest of Australian cinema. But for the filmmakers, like Thomas M. Wright, their films exist to try and make sense of the world that we live in.

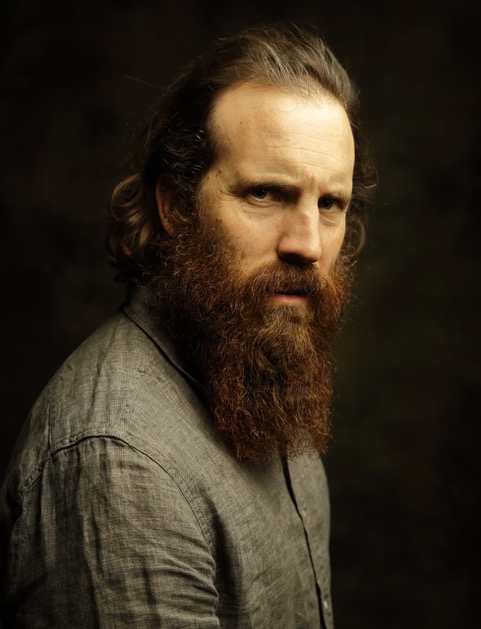

Within this interview with Thomas, he talks about that introspective journey in his films and the questioning relationship that his characters have with one another. The mirrored imagery of Joel Edgerton, Sean Harris and Wright himself is obvious – each figure is adorned with a scraggly beard and unkempt hair – and Wright gives a curious answer to the question whether that was a pointed decision or not. Thomas is a generous interview subject, one who knows completely about the stories that he’s telling and how to clearly define that objective in an answer.

This interview starts with an answer to the question about what it means to be an Australian filmmaker working today, especially in the context of film festivals like Cannes.

The Stranger is in cinemas from today, and will arrive on Netflix on October 19 2022.

Thomas M. Wright: I think it’s an interesting marker that this film it was the first Australian film in Un Certain Regard in eight years since Charlie’s Country. And we are there in a lineage of films that includes Ten Canoes, Samson and Delilah, BeDevil Tracey Moffatt’s film, Toomelah also, Ivan Sen’s film, all these extraordinary works of Indigenous cinema. Formative works, I think of Indigenous filmmaking. That we’re there as a psychological crime thriller is really unusual. And I’m so thankful that we figure anywhere in that lineage of Australian films.

But then also to be then bought worldwide by Netflix and be going out to 224 million people on October 19. I’ll be fascinated to see how people respond to the film. The film had a really emphatic response in places like Spain and Italy. I’d be fascinated to hear what the South Koreans make of it. For me, it feels like, in some ways, it’s more like a kind of South Korean film, not consciously, but when I reflect on it. Maybe because it’s on the one hand, it’s highly conceptual. It’s very propulsive. It has this complex narrative structure, but it’s also a deeply psychological film. And I was aware that I was doing that, that was part of the structural formulation of the film, to think about something that was going to be structurally complex and taut, but deeply immersive psychologically, but was using a kind of forensic language that you actually had to work through that was putting the audience in the position that they’re in almost more in a documentary, where you’re piecing together clues to make sense of what’s happening in the film.

Acute Misfortune was a profound, brilliant film. It was great to be able to experience how you’re progressing as a filmmaker. And it The Stranger is very impressive.

TMW: Thank you. I think it’s an interesting conversation between those two films, [it’s] probably something I’ll be able to reflect on in a good two decades. There’s definitely a through line there. I wasn’t from a film background, so I hadn’t written or directed a film at all. I hadn’t made short films, or music videos, or commercials or had any of that kind of that apprenticeship. When I walked on set to direct Acute Misfortune on the first day, it was my first day of directing film. A steep learning curve doesn’t even begin to… it was probably more just like an absolute fucking mess. But the lessons learnt were really extraordinary. The Stranger was an opportunity to kind of reconcile some of that, to continue on from some of those lessons, but also to resolve some of those mistakes as well.

Throughout these two features there is this interesting thread where you have protagonists who are questioning themselves, and they’re questioning somebody else. Whether it’s a journalist or a police officer, there seems to be this interrogation of figures.

TMW: They’re also unreliable protagonists. They’re unreliable perspectives. And they’re both films about relationships that began on really shaky footing. For me, I always describe Acute Misfortune as [a film] about a relationship based on theft. And The Stranger as a relationship based on lies.

How do you see yourself factoring into that? Do you see yourself as interrogating both of those figures as a director and a writer?

TMW: Definitely, definitely. I’m not interested in uncritical relationships with protagonists. I don’t have an uncritical relationship with myself. I think if you did, you’d be profoundly unwell. I am interested in that really thorny terrain between the person’s inner life and their actions and the whole range of complexity that begins to happen once you put two people together in a really compressed situation.

I find human relationships very difficult and very complex. And stories are often a way to simplify reality and to make reality manageable and digestible. Even if you’re dealing with complex and thorny stories, it’s a way to meditate your way through some of those questions. On a deeper level I think that’s something that I’m really engaged in with both of those stories. I’m currently developing a couple of other films as well, and they’re completely different. They’re setting out on an entirely different path to achieve something very different with a very different kind of filmic voice. It’s still going to be dark. I can’t come out into the light too much.

Your work is fascinated by trauma and the way that it represents itself and emerges within people. Acute Misfortune does it in a very explicit, quite intense way, and The Stranger does that too. I’m fascinated by what you are trying to divine or maybe glean from the cinematic tea leaves that you’ve created.

TMW: Some of that certainly has to do with my own experience of trauma. And that is very much there in The Stranger. There are certain parts of The Stranger that are intensely autobiographical, in some ways. And probably more psychologically autobiographical, than anything else. And I’ve never actually said that before. I think there’s truth in that. I think the film is a really visceral description of a psychological state. There are a lot of things about this film that feel very fated.

The film that is there is so close to the original film that I described to my collaborators. I’m very proud of that. Even though there’s obviously a lot of things that changed and it changed by the necessities of filmmaking and by working with your collaborators and really taking on their contributions in a really deep and very authentic way, the tunnel that that film exists in is very, very close to what was originally envisaged. It was a visceral film to make. A very difficult to make, very difficult material to deal with and to invite into your home. Obviously, nothing compared to the real trauma that people who were actually affected by these events face.

You asked about that experience of trauma and kind of unpacking trauma and lessons learned through trauma, that’s in Acute Misfortune, and that’s a stated intention of Adam [Cullen]. Adam is like, “You don’t know shit until you live it. Until then it’s just a fucking idea.” [A] very naive thing to invite in when you’re talking about the type of trauma that’s actually involved in a film like The Stranger. There’s a great privilege inherent in that kind of perspective that’s not there for the intimacy of that trauma and the personal relationship that’s present in The Stranger.

The Stranger is effectively Acute Misfortune turned up to level 40.

Certainly, I think there’s a deep feeling for victims in both of those films. And a sense of moral complexity in the shade. But The Stranger has a much stronger moral perspective, I think, than Acute Misfortune. And Acute Misfortune is as much judging the protagonist as the antagonist. I was always aware that the idea of having to write the truth of another person and have some objective truth of another person was going to be a flawed idea at the centre of that film, and the way that that manifests in The Stranger is very different because you’re dealing with these much more fundamental human aspects of chaos and the need for order and a deeper moral perspective that was there in the writing of the film.

And an unconventional moral perspective, I think, too. There’s nothing in the moral rulebook that says when you’re telling a story don’t show the victim, don’t represent the victim, don’t represent their family. But I felt that I had no right to. I felt that I could only diminish them. And I did not want to in any way be guilty of using people’s trauma to validate a story and that’s why it’s a story told about people who are one step away, but who do give years of their mental and physical health to resolving these sorts of cases for strangers. Because when events like this happen, they do shake the foundations of our society, they do change the way that we relate to one another.

And I think when you’re from a country that’s defined by hidden violence and violence that’s present but we’re unable to reconcile ourselves to it, no wonder that makes itself so often the subject of our art, whether it’s music or visual art or cinema or literature. That’s why it was important for me that this film was about an attempt to make meaning in the wake of violence. And I know this is all quite oblique in some ways, because I’m very conscious that on one level this is a film about a police operation, it gives you that binary nature of ‘here’s the good guy, and here’s the bad guy’. They’re the two sides of the coin, and they certainly mirror and reflect one another.

But I think there are some deeper things that I wanted to engage there about the lineage of Australian crime cinema, and films about violence in this country. But also what it is to set a film in the wake of that violence, where even though violence is the reason for that film, it’s not its subject, and its subject is really an attempt to make meaning when violence threatens to render things meaningless and to find the connection between people. Those sorts of questions are what led to the casting of my own son – that’s my little boy who plays Joel’s son in the film, that’s my little boy Cormac. Because he’s my stake. He’s my emotional reality. [He’s] everything to me. He’s my only child. And that’s what’s at stake for that central character.

There is a visual style of you – the beard, the long hair – that is replicated in the two characters. Is that a pointed decision?

TMW: No. No, it’s not. I don’t have my full beard at the moment. To be honest, I’ve also got one of those faces that if I don’t shave twice a day, I’ve got a beard in four days. I suppose the only thing I would say about that is that we were all conscious of the fact that this was a film about hiding. And truthfully, I’m a very, very private person. I really try to deal with the world through my work. And through the subject of that conversation, on ongoing conversation that you’re having through your life, and the process of talking to people about that work is difficult for me, because I feel that a film should be able to say all that intends to on its own and on its own terms.

And I like to hide. Which is funny, because I’ve obviously worked as an actor at times too, but that’s its own form of hiding, and when you look at those films, they’re also about the kind of performance of the self, a presentation of a version [of the self], and usually a version of the self that’s defined by work. In fact, for every one of those four central characters, it’s how you’re taught what to be, and what to want, and a kind of codified language of behaviour. That’s very explicit in The Stranger. But for me, that was also that learned behaviour of journalism, or the art world in Acute Misfortune. And in this, it’s this kind of criminal enterprise and these two people that start to look more and more and more alike and start to dress like one another and sound like one another and turn into one another. I don’t know whether that’s some deeper nature/nurture conversation I’m having about human beings or whether it’s more of a Jungian thing about shadow states and hidden aspects about the self and the subconscious. But it’s a conversation without end, whatever it is. I think it’s something that you can return to over and over and over.

This interview has been edited and condensed.