Perth-raised filmmaker Tim Barretto has seen the world. Growing up in Bassendean, learning about film production at ECU in Mount Lawley, Tim eventually moved over East to work on television productions. In the meantime, he’s also lived and worked as a filmmaker in Indonesia, creating documentaries as an outsider looking in.

Zooming in from New York, Tim joined up with Andrew to talk about his feature debut Bassendream, which has its world premiere at Perth’s 25th Revelation Film Festival. The opening night has already sold out, with limited tickets available for the Luna SX session. In this interview, Tim talks about 90s nostalgia, bringing an authentic touch to the voices in the films, and shooting on film, plus so much more.

This interview has been edited for clarity purposes.

Take me back to when you first came up with the idea for Bassendream.

Tim Barretto: It was probably ten years ago, and I was chatting with people that grew up in Bassendean. A lot of people in Perth and outside Perth had moved on, have done quite well in their fields, and lots of them have come from Bassendean. I always wondered what was special about that suburb that made people have that creativity and that freedom to explore ideas and not feel vulnerable in that state.

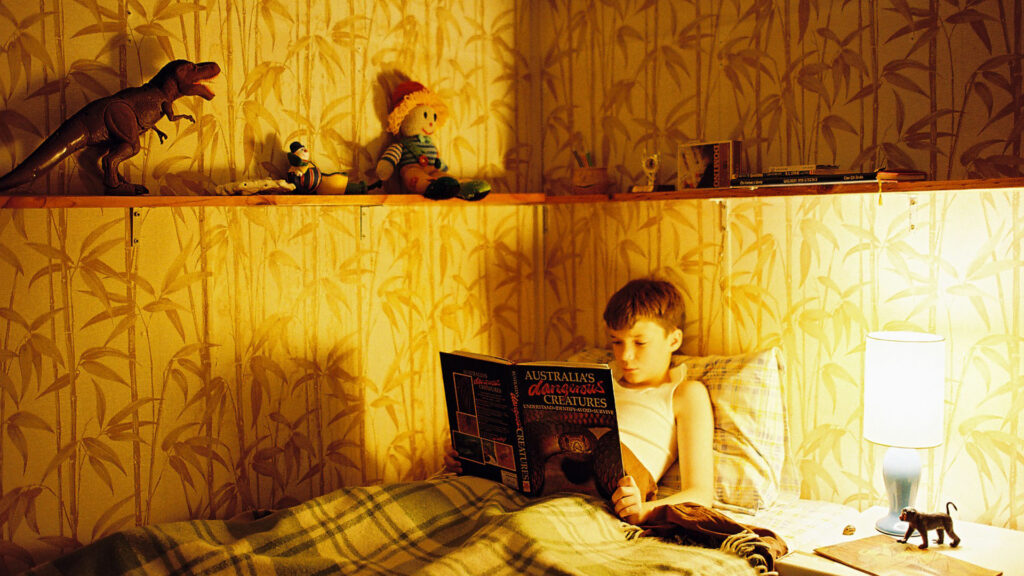

I always felt like that was a unique experience. I had my dad doing Tai Chi around the backyard, that disconnection between the adults and kids. I don’t remember doing family things. I just remember being with the kids and then going bed, being out on the street and then going to bed. So I thought that was an interesting dynamic to explore in Australian culture, that we hadn’t really seen much on screen.

I’ve seen a lot of suburbia presented in a really dark way. I think we get that a lot in Australia. I wanted to make a film that was more fun and not so grim, I guess, even though it has a dark element at the end which sort of pulls away really quickly. It doesn’t have to be honest, I wanted a heightened sense of a child’s perspective of what they see as the suburb and make the suburb the central character.

The writing process has been so skewed, like I wrote half of it in Taiwan. I had to get out of Australia to write about Australia. That’s sort of what it felt like. And I shot it over two summers as well, so it wasn’t a full on one set shoot. After I got the footage back from the first shoot, I was like, “Okay, I kind of know how to write it from here.” I gave it like a test shoot, essentially, which most of it made [into] the cut. And then I developed the ideas and the characters from there and I kind of worked out what I was missing.

But that was kind of the refreshing thing about shooting on film — you’ve only got so much film and you can’t go back and review it quickly. You have to wait two months to see it. It’s kind of a good place to be in as well as a first-time filmmaker, you can be a bit more forgiving of yourself.

You’ve done shorts, you’ve done docs. Doing a fiction feature, that’s a whole new world, isn’t it?

TB: It is. And I guess I was trying to be super safe in the way I approached this film, to do my first feature in that I chose my hometown, the town where my granddad grew up, and my family are there and there are support networks there. There’s houses to film at and there’s emergency levers I could pull.

In terms of story, we’ve got a Magnolia-esque style where I get to really chop it and throw it out on the cutting room floor when I needed to. I didn’t have to keep anything. That was really a nice place to be in, being the editor as well. Story-wise, you can be a bit looser, and I know that can be a challenge for some audiences. It’s interesting, the wide network I showed it to probably a year ago or two years ago which is still a different cut to what you’ve seen — lots of [viewers] from different countries connected with different characters.

That was one of our questions: what was their favourite character? They have names but they don’t really have names that are memorable, it’s more just that familiarity.

You must be pretty excited to launch the film at Revelation.

TB: It’s been a long process. It’s been exhausting getting it to the finish line. I know it’s not a typical movie. It’s [got] wonderful elements to it, I know where it sits, and I know its flaws, and I love all the charming elements. I’m really comfortable as a first dramatic feature where it sits for me.

What sort of film did you shoot it on? And when did you shoot it?

TB: We shot it in summers 2016, 2017. We shot it on 16 millimetre on an Aaton XTR and an LTR. We managed to talk our way through from TAFE and Curtin University. I went to ECU.

Keith, George, Andrea and Tanya were my film and video development lecturers. They gave me a lot of inspiration to be a filmmaker that had confidence to do a sort of off-centre film like this. It’s shot on Kodak Vision3 500T and 50D. I wanted the daytime stuff to be as close to 35 millimetre as possible so fine grained as possible, which I think it achieves when you do see it. Obviously, 16 millimetre is a bit noisy and it’s a bit grainy, and there’s dirt on there. If you have Hollywood, you get it touched up. I do like to keep it as clean as possible but that is the product.

It looks great. Another of the filmmakers who’s going to be playing at Rev is Chris Elena with his short film Refused Classification. And he has found the difficulty of shooting on film is not because of the actual shooting on film part, but because people are coming along and going, “Well, there are digital cameras, why aren’t you shooting on digital? It’d be much easier.”

TB: This movie wouldn’t have been made if I chose to shoot on digital. It just wouldn’t have been made because I wouldn’t have had the help or the seriousness or the support that came along with shooting it on film. I think we would have been bogged down with the stresses of the rushes each night, and probably felt a bit flat in what we got. Because you’re critical at the time of performances. Like yeah, they’re not perfect performances all the time, but there are some endearing performances that the kids have that are really honest, and they’re two-take performances. I’m like, “It’s $1 a second. Don’t fuck it up.” (laughs) You can give them that line and it’s kind of fun to put that pressure on a kid, and they are receptive to that. I don’t think it was cruel to put that pressure on people.

Also the whole set, they’re not on their phones. We’re only shooting four minutes a day screen time, we’re not shooting much. We’re not doing many setups, we’re not moving the camera heaps. So when we do it, everyone shuts the fuck up, and then we just do it well, as best as we can. I think you get that level of seriousness, and no one’s got a split or a monitor, and that’s kind of refreshing as well. But yes, you’re left with getting it later and you have to deal with what you’ve got. Whereas when you shoot on digital — and I love digital equally, like I’m not one way or the other, I just think [they have] different purposes. But you give me a choice, every time I would say shoot it on film. But I’m not anti [digital].

But it just feels a bit more honest, in that sense. (laughs) But also, I wanted to make a film. I wanted to make a movie and that felt like the way 90s independent movies were shot back then, it was 16 millimetre, like [Kevin Smith did with] Clerks. That’s what they did. They got a camera from where they could and then they just put it on their shoulder or on a tripod. We didn’t have any dollies, no dollies on that whole film. Really simple, just be smart.

You’re limited with those restrictions, and restrictions are a godsend, I think, for independent filmmakers. Don’t look them as limitations, look at the limitations as opportunities. How do you work with what you’ve got? We rented a house in the second year [of filming]. Ten characters used that house. That was one backyard, one front porch, one kitchen, one living room, one bedroom, another bedroom, computer room. Just set dressed differently. That innovation is fun, I think. And also it was also the production house. You don’t overcomplicate it.

I think the most liberating thing — and I learned this from working on television in Sydney — like Australian telly, movie-making is not real. It’s a fake land. So don’t try and be too authentic. Make it work. If you have to pull the chair up really high because it looks better, just make it look better. It doesn’t have to feel real in the space for the actor, it doesn’t have to be fully method for the director. Some directors work that way and that’s fine. But I love the playfulness and the trickery and I always like that style.

Shooting on film captures the warmth of summer better than digital could.

TB: Absolutely. It handles highlights differently, yeah.

And a WA summer is different than most summers.

TB: Harsh, it’s brutal.

You’ve captured that brilliantly on screen. I’m curious about how you immersed the younger kids into the era. [With] some of the lingo, did they understand it?

TB: They embraced it. We workshopped it, and we workshopped different lines, especially when we’re doing the critical lines. You work out what works for them and what sounds authentic to them. We know what the objective is here, calling them a ‘pooncy’ kid or that sort of thing. As you know, that’s how we used to talk. We always used to tease each other in that way. And it’s not something to ignore and it’s not something to celebrate. It’s just something that is what it was.

I tried not to be too challenging in the dialogue. I’m not here to make a statement. It’s not a film trying to make a statement about certain culture or one culture versus another. I wanted to make something inclusive, because I think growing up as a kid, you feel like everyone’s inclusive, like Indigenous people on a football team. I didn’t feel there was that separation, but we still used racist language at the time, and that wasn’t my fault. [We] weren’t aware. So I tried to keep it pretty mellow in that sense, but being aware of it as well.

That certainly made me think back on growing up as a kid and the things that were just kind of commonplace for white Australians. It’s both a stark reminder of how far we’ve come and it’s kind of a relief to be able to go, “No, I’m not actually forgetting this stuff that happened.” And it’s not a prominent thing in your film or anything.

TB: No. And as long as you grow up being aware of it. You don’t have to then go and punish yourself retrospectively. I think you just be aware of it and you move on and you make choices how you direct this, and things like that. I didn’t use any racist language.

With Cezera [Critti-Schnaars] who played the Indigenous friend with the two girls, I got her to write her own scenes. She did that because I was like, “I want this idea that this Indigenous girl grew up in the suburbs.” She doesn’t go on walkabout with their families out in the country or anything like that. So I was like “Depict that.” And that’s when she was like, “What do you think, I know how to like cook a kangaroo and season it with witchetty grubs?”

I loved that line.

TB: That’s her line, she wrote that. I’m so happy that she got to write that for herself. For the character, I think it’s important to get rid of that stereotype as well, not ignoring the stereotype.

I’m a 90s kid so I relate to a lot of the kids doing the kid things. Although I’m more on the line of the kid who gets his bike thrown into the tree, that was me.

TB: The strict kid. The outsider.

Looking at the bullies, it’s both this feeling and thinking “I want to be part of that, but also they’re the worst people in the world, I don’t want to be part of that.”

TB: I know, I know. You can live in your own world and the world itself, the suburb, it’s a bubble, it’s not specific to Bassendean. Every suburb is like a bubble. And when you exit that bubble, something feels different. So you have that really safe zone that when you were a kid in the 90s, you had that freedom to roam around. I always wanted to separate the adults from the children as much as possible. That was a really big thing, they don’t really have scenes together, but they sort of do. I kind of wanted to keep that.

I really liked that sequence where the older woman is chasing the kids.

TB: That’s sort of based on a true story, that happened to my brother. And it was this crazy lady in bras and knickers.

I think we’ve all got this older person story from growing up where they’re trying to discipline strange kids who were [misbehaving].

TB: Absolutely. You used to always get in trouble from other people. Everyone used to tell you, you couldn’t get away with that now. You’re not allowed to tell anyone’s kid off apart from your own. (laughs)

(laughs) Which is fair, I understand that. But on the other hand —

TB: Well, that made you a bit scared as a kid. You treated situations like you could get told off. There’s a bit more confidence now, bravado that kids have which I don’t think we had so much.

I don’t know if this is intentional or not, but there feels like this tinge of Neighbours with the font of the title of Bassendream.

TB: Yeah, that is very Neighbours.

And then we’ve got the cut to the WA Salvage ad. To me, what I feel about the film is that it feels like it’s challenging that manufactured concept that suburbia can be so dark, but on Neighbours it’s like this manufactured sheen of positive suburbia. And this feels like it’s challenging both, that suburbia is not super glossy, but it’s also not super dark. It’s just real life.

TB: It just is. I’ve never wanted to make something highly dramatic and highly emotionally driven. But there needs to be a rawness in there that is honest and real. But then there’s so much playfulness. Exactly what you said, I 100% back what you said.

What I wanted to achieve is something that has a bit of everything, and it’s all going to be okay in the end, even when it’s not okay. You know? Life is challenging and it’s not that period that’s challenging. Life is probably more challenging now, it’s probably simpler back then. We had our taglines before we had all the answers. Was it simpler? Or was it harder? I’m not really sure. I haven’t really worked out if life was better or worse. That’s just how it felt. No helmets and running around skateboarding and all of that stuff.

And being just kids. And the only pressure coming towards us is the fact that it’s going to be night-time soon —

TB: And then you have to deal with your parents. (laughs)

What I do really like is that this isn’t some rose-tinted look at the nostalgia of the 90s. How important was it for you to pull away from that kind of glorified nostalgia?

TB: Well, I was really scared. I didn’t really want to make a nostalgic piece. I wanted to make something that had its own voice. It’s funny because I showed it back in 2017 and 18. And now there’s been a huge wash of nostalgia and we’ve seen films coming out set in the 90s and everything like that. I wasn’t aiming to be on that wave, it just happens to be on that wave now, which is totally fine and probably is beneficial for audiences accepting the film being a period piece.

But yeah, I wasn’t trying to just nostalgia-wash it or putting things in for the sake of nostalgia. Like the ads and everything. I was like “No, there needs to be an ad break now. (laughs) I don’t know how to continue this movie right now, I just need to put in a break in.” That’s sort of what it felt like.

And then it was really cool exploring all these ads and I was looking at old Ansett Australia ads, but they’re much harder to get. The WA Salvage one – that company doesn’t exist anymore. Ansett doesn’t either. But Claudio [Versaico], he’s contactable, I can get approval from just him. But yeah, I did want to have a few ads scattered. Having tested with a few people, they were a bit [confused] at times and still probably are a bit confusing and jarring. But I still like the way you get pulled out of the film and then you have to reintroduce yourself into it.

Let’s talk about the music. You’ve got a couple of big hits in there. How did you go about organising that and getting the approval for them?

TB: Just being very stubborn. That’s why it’s probably taken this long to release. Getting initial quotes, music totals in tens of thousands of dollars, and then waiting and recontacting them along the way. It was really an independent production. We really got Dumb Things approved first. And then once one happens, they all kind of all [happen].

[People were] like “Just make a track that sounds like it.” And I was like, “I just can’t, it feels wrong. I’m happy just to not release it yet. I’ll get some more money maybe, and then try and reapply or ask them.” I always wanted to get money to handball it on. But that never happened.

We had a person come on a couple of years ago just before COVID, and then COVID hit. Everyone just went deaf at the time, we all went silent. I wasn’t pushing anything and I was trying to pack up my life in Indonesia. It was just messy. So I left it.

Really, it was Ian [Hale, producer] that kicked me up the bum. Ian came on and he’s good like that. He was like, “No, you just do it. I get what you’re trying to do.” And I [went], “I’m a bit deflated, I don’t know how to get to the finish line. [The movie] still needs cutting, I don’t have sound design. I can do the grade, like that’s fine. But I still need a sound designer, it needs to sound like a movie.” All the other bits and pieces, that EP stuff and producing stuff is just messy. It’s just hard. So you need that extra person to keep you up above. Ian was that.

He’s done a really great job of curating and championing WA films.

TB: It’s awesome. I’m a nobody in Perth. Like I lived in Sydney for seven years. We used to drink at the pub, like when I was in ECU at the Scotsman I used to have a beer and chat to him about it. He heard about Bassendream ten years ago, “I’m gonna make this movie called Bassendream. I don’t really know how I’m going to do it, but I’ll do it.” And I made a movie called Before The Dream set in the 70s in Bassendean, just to test it on 16 mil. And that did really well at the Australian Teachers Of Media Awards. And it was slice of life shortcuts and vignettes. It works there. And I was like, “I can’t believe people like that” (laughs) in that sense. I was like “I like that sort of movie.” It’s nice.

I think in Australia and probably more specifically WA, we try and compete too much rather than try and have an authentic original voice. And I was really conscious of that, because we tried to go too clean. And that’s totally cool. Like I love clean, I love a good three-act structure. But if you get the opportunity to challenge it or do something different, then I was like, “I’ll take it.” I had the support of my girlfriend, wife now. She studied film theory and she was like, “No, let’s make this movie. Let’s do it.” I needed that support.

This kind of film is the sort that I really love getting lost in because it isn’t the sort that holds your hand.

TB: Absolutely. I wish I had spent more craft trying to tell some of the stories better. But that’s my learning curve as well. There’s something beautiful about the shifts and the flows and the peaks and the troughs. I was just really trying to write it as a vibe, I was trying to write the edit as “What do I need next? What do I need now?” Rather than “What does the story need to give to the audience?”

I was really conscious of making [it as] short as I possibly could as well and not trying to over-indulge in stuff. That I find is a bit punishing and that’s just a maturity thing. Probably if I cut it five, ten years ago, I probably would have over-indulged in a few things and left scenes in that probably didn’t need to be there. It’s good to be ruthless, in that sense.

The title is Bassendream which suggests sleeping and thinking and stuff like that. What does that do to you, to have this film in your mind for ten years, dreaming about it, sleeping and thinking about it? How does it impact your sleep patterns and your dreams and thoughts?

TB: It never felt wrong. It never gave me nightmares, never kept me up at night. I was always proud of what we achieved in self-producing it. So I never got haunted by it. I never felt pressured to finish it because of the way we made it. And I think that was really important.

Sometimes you can make a film where you pull help from places where you then have to answer to people, whether that’s yourself or crowdfunded or that sort of thing. But the way we did it was in a really honest way with the cast there. Some got paid bits and pieces.

But we were really generous the way we shot, we didn’t over-commit to the young kids. We didn’t work them longer than eight hours, they were really strict about those protocols. And I think it was really important that we could walk away even if we haven’t got a film to show for it after five years, that everyone still had a good time in the process, and they didn’t walk away feeling bitter. So that was really important for us. I think people have anxieties about that. It’s about communication, especially when you get a cast this big. I did have slight anxieties about communication, but I always knew that I never did the wrong thing by them.

But yeah, in terms of Bassendream, it was the dream. That was the dreamland. That’s where ideas were developed and where we grew up. It just had the ring to it. Bassendean Council contacted me, people have made T-shirts for it and stuff. So I’m glad it’s sort of been adopted by the suburb.

I felt recently [the film] needed a subtitle, like A Suburban Odyssey or something like that just so it didn’t pigeonhole it for a wider audience, Australian-wide, but yeah, I’m not sure that could be a possibility. I kind of still want to ask people about that. But it’s just the dream. You know, that’s all it is.

I think it works well. I mean, I live in Booragoon. We call it [the shopping centre] Garbo. There’s this affectionate term that we have for our own suburbs. So Bassendream fits for that.

TB: I don’t know where it came from. It was us developing it as well as friends and a couple of friends that lived there and chatting about it. “You’re going back to the dream tonight?” It sort of happened organically, that title. It was really nice.

This is going to be screening at Revelation. What’s that like for you, being part of such a big festival?

TB: It’s great. Like I went when I was a uni student and got the gold passes back when it was at the Astor. And it was the best. I got to see all those experimental films. There wasn’t as much local content back then. So it’s nice for them doing more local content. I always loved Rev. I’ve always tried to be a part of it. I’ve been in the Super Eight competitions and all of those things. I had a couple of short films in there, but having a feature there and having that was always sort of in the back of my mind. I was like “It’d be a good Rev film. If I could get into Rev, I’d be really happy to have that as the world premiere.” Keep it in WA. That’s what I wanted to do.

[I’ve] always been fond of [Rev]. Always attended when I could. They program so well. I enjoy the vibe there. I wish it had the Astor as well. I really miss the Astor, to be honest. It’s got a good energy.

And I think we need to bring the youth to the festival and I think that’s really important. Now that I’m an old guy, I want to see what young kids are doing. They’re the ones that are not as bitter. (laughs) They’ve still got the hope in the eyes which is fun. It’s always refreshing speaking to young kids that want to be filmmakers, because they have that attitude, that look in their eyes. Not that I’m old. But I feel a little bit exhausted.

You’re not nearing the pension age.

TB: I still feel young in my filmmaking career, I still want to make movies.

What does it mean to be an Australian filmmaker for you? And what does it mean to be a WA filmmaker as well?

TB: Well, WA I have an interesting relationship [with] because I had been away from WA for eight or nine years. So coming back to WA during the pandemic, I [said] to my wife “Let’s not go back to Sydney, I don’t want to work on any more sets, I’m done with 50 hour, 60 hour weeks. I just want to do something different.” I think you can see it in a different light coming back. It’s that outside of you when you were an insider, it’s really nice.

WA has a lot to offer. I think we lose a lot of talent over east. I don’t have any answers. But I do think there’s a lot of talent that comes from WA in all forms of the arts. There is a community but it’s small and it’s competitive and that’s what’s really tough. And I’ve come back in the last two years and not even said that I’m a filmmaker. I just want to blend in and observe. I’m in observation mode. And that’s kind of nice and refreshing. I’m not in a rush to make my next movie.

I have ideas for my next movie, but I’m not in a rush. There’s stories to tell everywhere and I’m all about what’s achievable, what’s producible. WA has a big advantage in that accessibility is easy and cost of production is cheaper. And we need to take advantage of that as an independent filmmaker.

And going back to that first part of the question, what does it mean for you to be an Australian? Is that something that you like showing on film?

TB: Yeah, I had big interest in Indonesia, and you probably saw I did documentaries there. I think telling a story as an outsider is a really interesting place. It’s more vulnerable when you’re telling your story, obviously. But to be an Australian filmmaker, like my idols would be Rolf de Heer. I think his approach to filmmaking has been one of the most inspirational, and I think he did his first movie using his own family and doing it in his home and that sort of thing. I remember hearing that and being an Adelaide filmmaker, close to Perth, being in a small town.

I think you can do it, but be realistic about it. And I probably wasn’t realistic about it at the beginning of the journey. But having not been in a rush, I got to grow with the journey and then learn more about what hill that was to climb.

Being an Australian filmmaker to me I don’t consider as being patriotic. I think it’s more about being real. I think Australians when they do honest films, they’re just the best. The honest ones are the best. And that’s when we thrive, when we’re honest about our character and who we are. And, you know, the reality of the context of how Australia as a colonial state came to be here as well. It doesn’t have to show that theme. But I think we just need to be honest about immigration and all that sort of thing.