Last year, Avengers: Endgame, the twenty second entry in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, earned $2.798 billion worldwide and thus becoming the most successful film of all time (unadjusted for inflation; with inflation, Gone with the Wind’s Scarlett O’Hara beats Avengers’ Scarlett Johansson with a fistful of cotton). Toss in several other billion dollar grossers and Joaquin Phoenix’s Oscar-winning turn in Joker, and 2019 may well represent the cultural and commercial apotheosis of the superhero/comic book movie.

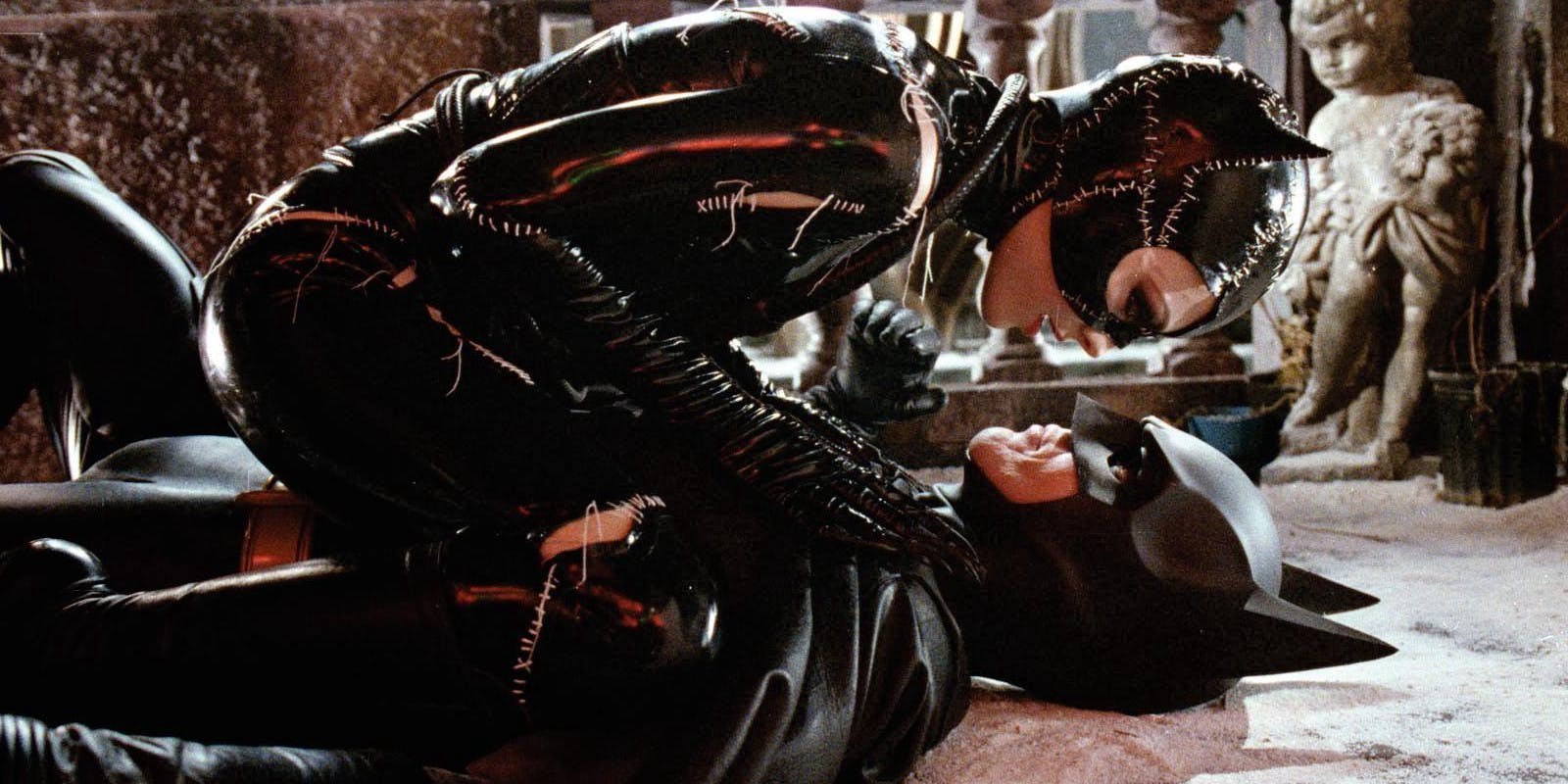

My two cents: the genre peaked from 1989–1992 with the five film punch of Batman (1989), Dick Tracy (1990), Darkman (1990), The Rocketeer (1991), and Batman Returns (1992).

I’m not suggesting these five films mark the genre’s cultural or commercial peak—though some were very successful—nor its critical peak—although again some were well received critically. Nor do they mark its imaginative pinnacle, nor its apex of ambition: the scale and world-building of, say, 2019’s Aquaman, with the aid of twenty-five plus years of advanced visual effects wizardry, leaves these five films out to dry (pun intended). Where recent comic book films paint on a cosmic canvas, this quintet is distinctly earthbound, and arguably shares more DNA with the Clint Eastwood and Charles Bronson tough guy movies of the preceding era. Moreover, they’re very white and extremely masculine films, both in front of, and behind, the camera — with little of the diversity on display in recent comic book films like Black Panther, Captain Marvel, Wonder Woman, or Birds of Prey.

But as self-contained films untethered to and unburdened by larger cinematic universes — and as (mostly) auteur-driven works not beholden to any in-house style — I’d argue these five films are more interesting, more stylish, and more playful than the bulk of the superhero features that followed in their wake. They also represent a last hurrah for rendering super-heroics onscreen largely sans digital effects; later in the decade, computer-generated effects would saturate comic book films like The Mask, Spawn and Blade. The fact these films wrangle their heroics onto celluloid with models and matte paintings and without the luxuries of CGI makes their accomplishments more impressive. These five films are flawed but special and speak to the elasticity of the superhero movie even in its infancy. They are very different beasts to the comic book film as it exists today; they look, feel, move, and sound different in a genre where time isn’t always kind. In some respects they’ve aged like fine wine, in others they’ve dated poorly. And apart from Batman, awareness of their pioneering status has dimmed with the passage of time. This article offers up some context, wipes away some dirt, shines some appreciative light upon, and makes a case for the class of 1989–1992.

In a recent piece here on The Curb I cited Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and John Landis as directors who occupied primetime space in my youthful viewing. To this list I’d add Tim Burton, who between Pee Wee’s Big Adventure, Beetlejuice, Batman, Edward Scissorhands, and Batman Returns owned a few years of my childhood. With Batman, the filmmaker wrote a blank cheque for the rest of his career, but where its sequel is unfiltered Burton, Batman sees him working within studio imperatives.

The film pits Batman/Bruce Wayne (Michael Keaton) against crime kingpin Jack Napier/The Joker (Jack Nicholson), and tasks the Dark Knight with thwarting the Clown Prince of Crime’s nefarious intentions for both Gotham City and his love interest Vicky Vale (Kim Basinger). The top-billed, handsomely-paid Nicholson plays to the rafters in his outré turn, kicking off a bizarre tradition of the Joker as the Hamlet of postmodern blockbuster cinema; an enigmatic role essayed by former Oscar winners (Nicholson, Jared Leto) or gifting actors their winning shot at Oscar gold (Heath Ledger, Joaquin Phoenix). Meanwhile the unconventional, puffy-haired, craggy-faced, pointy-lipped Keaton broke the typecasting mould for both comedy and action stars, playing Wayne as a broken space cadet and Batman with steely yet soft-spoken gravitas, conceding to but ultimately owning like a boss the limitations of a largely immobile costume.

At the time of its release, the spin on Batman hyped it as the ultimate take on the Dark Knight onscreen: a mega-budget, serious treatment of the material in contrast to the (still-great) campy Adam West-starring TV series of the 1960s. With the gift of hindsight, there’s no ultimate take on such malleable material, with every version having its rightful place in the canon. Further, looking back there’s something rather chintzy and goofy about Burton’s Batman despite its grandiose aspirations. Its larger than life status was partly a triumph of marketing and corporate packaging, from the cultural ubiquity of the Bat logo, to the Prince soundtrack, to its Nicholson casting coup which harnessed his superstar status in much the same way Superman had harnessed Marlon Brando’s cachet a decade earlier. The film supporting this massive hype machine is somewhat more modest in its ambitions, and though all the dollars from its generous budget are visibly onscreen in the large sets and costumes, it feels rather quaint thirty years later, and comparatively claustrophobic and stage-bound.

History has borne out that Burton is a great visual stylist (albeit with a now familiar bag of tricks and an increasing dependence on CGI), but not exactly a teller of rounded and cohesive stories. Batman exemplifies this: it’s a film of great moments, scored to a bombastic earworm of a theme by Danny Elfman. Moments like this, and this, and this, and this, and many more still pop thirty plus years later. Burton pulls from his own personal pop culture bank in building atmospherics—there’s a touch of Universal Monsters, a smidgen of Hammer, a whopping dollop of German Expressionism—and as a former animator has a knack for maximising the expressiveness of a scene by framing, timing, and holding a shot long enough so it imprints on the viewer. Such an approach—privileging an arresting image or scene over the integrity of the whole—is not inconsistent with the late 80s Hollywood aesthetic: Tony Scott’s Top Gun is chockfull of stunning shots of jets in flight, but I’m unsure they ever stitch together in a geographically sound way. Batman’s colour scheme—contrasting Batman and Gotham’s blacks, greys and browns with the Joker’s electric purples and greens—creates arresting visuals. Lest I be an auteurist fanboy, credit’s also due to director of photography Roger Pratt, editor Roger Lovejoy, production designer Anton Furst, and costume designer Bob Ringwood, amongst others.

There’s a case to be made that the larger than life status of Batman outweighs the rickety frame of the film supporting it, and that the film coasts on its iconic moments to some degree. But those moments and images remain striking and indelible and play remarkably well thirty years later. Time will tell if any of the signature moments from comic book films of the last decade have similar staying power; I certainly can’t think of any from the noughties which have shown similar stamina.

Batman established a comic book movie template: pulpy retro heroics, highly stylised filmmaking, and a bombastic Danny Elfman score. The Rocketeer adopted a more classical filmmaking style and nixed the Elfman score, but delivered pulpy retro heroics in spades, whilst Batman Returns parted ways with the retro pulp angle but cranked everything else up to eleven. Dick Tracy and Darkman, the first releases in Batman’s wake, hit all three notes. There’s always some risk in assigning influence amongst films released within a year of each other, especially when one of those films is directed by the exacting and meticulous Warren Beatty, and indeed Beatty had toyed with adapting Chester Gould’s beloved Dick Tracy strips since the mid-1970s. However, the film is cut from very similar cloth to Batman, with a major star hamming it up as the villain (Al Pacino here subbing for Nicholson), a major pop star on the soundtrack (Madonna here subbing for Prince), and logo art that Disney tried (but failed) to make as ubiquitous as the Bat symbol ahead of the film’s release. Additionally there was plentiful merchandising on the side.

Beatty directed, produced, and stars in Dick Tracy as the titular yellow-coated crime-fighter, tasked with taking down mobster Big Boy Caprice (an Oscar-nominated Pacino) and choosing between the alluring Breathless Mahoney (Madonna) and the good-natured Tess Trueheart (Glenne Headly). Whereas Burton clearly gravitated to Batman/Bruce Wayne as a likeminded warped outsider, Beatty, like Tracy, was approaching his own fifty-something romantic crossroads, and the following year would mirror Tracy in choosing between continuing his womanising ways or settling down with Bugsy co-star Annette Bening. He chose the latter. He would also have four children with Bening, mirroring Tracy’s adoption of a young ward (a spirited Charlie Korsmo). Batman, despite famously having a young ward in print and other media, would not meet his onscreen Robin until Joel Schumacher’s 1995 film Batman Forever.