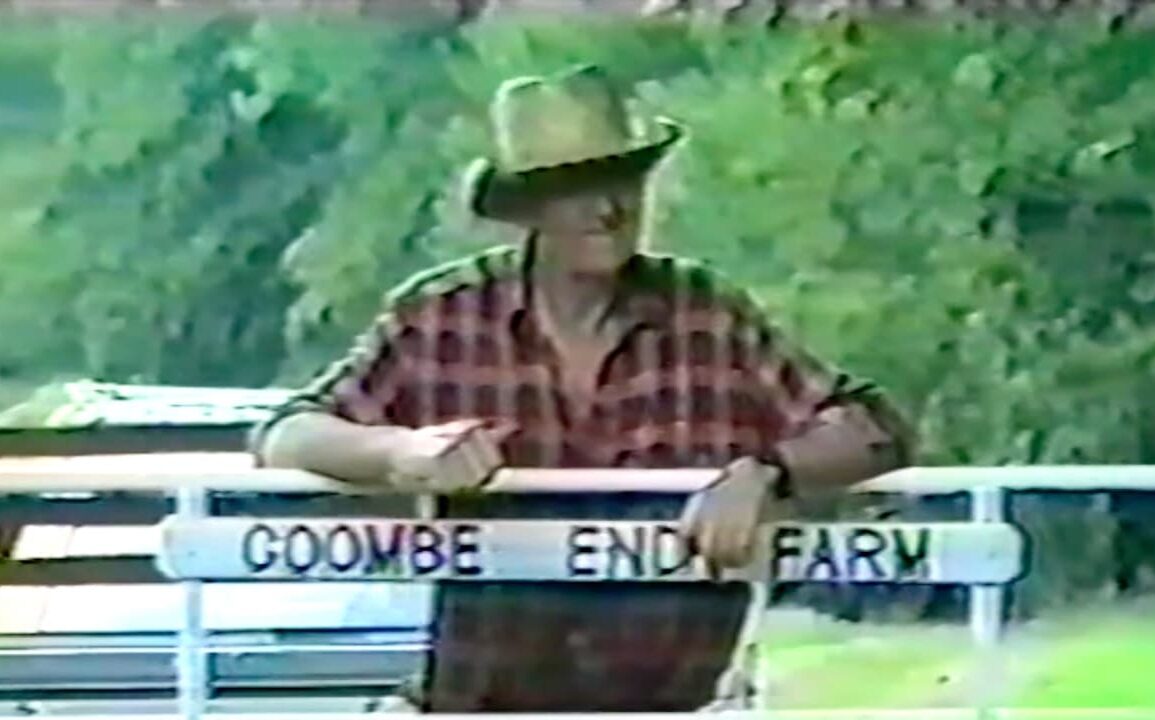

The name Charles Carson might mean little to most people, but to the rural town he lived in in the UK, he was a familiar friendly face with. Charles would share stories of his life on the farm by taking photos and make his own early-day memes, delivering them to his neighbours and relatives, eventually including VHS videos of his own skits and stories of his life.

In director Oscar Harding’s magnificent documentary A Life on the Farm, Charles’ VHS tape oddities are shown as inspirations and pioneer works of a late-stage filmmaker springing to life. With footage of cows giving birth, stories of dead cats, and a particular tour that Charles gives his mother of their farm, A Life on the Farm is a truly unique slice of documentary filmmaking that moves from being grotesque and laugh out loud cringeworthy, to genuinely endearing and moving, ultimately challenging the modern notion of how we treat the process of death and dying, leading to the realisation of what it truly means to live.

In this interview ahead of the Australian festival launch at Perth’s Revelation Film Festival, Oscar and producer Dominik Platen talk about the journey that took place to help realise Charles legacy on film, the growing interest in VHS film festivals, while also sharing their favourite Charles clip. This is a film you are not going to want to miss.

This is a very collaborative project, and indie films are always that way. Do you consider yourself an indie film?

Oscar Harding: I don’t know about Dom but I’m happy going by the title of indie filmmaker. We had a lot of support from the fanbase of Nick [Prueher] and Joe [Pickett] [who] are also in the film and came on as executive producers. So we did have a leg up and we’re very grateful for that. Not everyone does. But we got through that Kickstarter just by the skin of our teeth, a couple $100 over the limit.

Dominik Platen: It was pretty ambitious to do a micro budget. (laughs)

OH: Right. The moment we had to look at music rights, about a third of the budget got swallowed up in one swift day. That was not fun.

But it’s out. It’s in the world. Congratulations to you both.

DP: Thank you.

Are you flying across for the [Revelation Film] Festival?

DP: I’m in Sydney. So I’m not too far away. I relocated down here in September last year. I actually graded the film in Sydney. (laughs) It was pretty much done all over three continents.

OH: You did it in Australia, you also did it in France and Germany. And we had the sound mix done in Dublin, and we had the editing done over here. We had a little bit of post-production done in New York. We never set out to make it this globe-trotting. But you know, between COVID and everyone moving all over the world, it just worked out that way.

Did you have a narrative in mind for who you needed to interview prior to shooting? Or did surprises come along the way of “Oh my gosh, somebody’s mentioned this person. I’ve got to go and track them down and talk to them”?

OH: Definitely the latter. Right, Dom?

DH: Yeah. I would say we had a good list of people that we thought were good fits. Nick and Joe were our first talking point. Because we knew their stuff, we knew what they do. So Oscar, you approached them first. From there on, we knew that it was working with that kind of audience. And I think, Oscar, you found [Derrick] Beckles and [Davy] Rothbart.

OH: It was sheer dumb luck that we got Nick and Joe, and then the three fellas on the channel Everything Is Terrible. We had shot when this was a short film initially in early 2019. We interviewed one or two people and then I got a job out here in Milwaukee where I’m currently based and where we did a lot of the film. This is before COVID. I told Dom “I’ll be back. Summer 2020 we’ll finish this up.”

So just before we knew what was around the corner, I still had months stuck in America where we couldn’t do a whole lot. I knew that there was more of an audience out here in the States than there was in the UK for found footage and making fun of it and showcasing the stuff and celebrating these people and asking all these questions. So I reached out and by dumb luck, Nick and Joe, and then Everything Is Terrible within two or three weeks of each other, they were in Milwaukee, and they were all just hooked.

I tried to reach out to Derrick Beckles and didn’t really get a response, he’s a busy guy. [Nick and Joe] knew him personally, they recommended Davy Rothbart, they recommended Karen [Kilgariff], they found Thomas Lynch and said, “You should get this guy who will be amazing” and then I reached out to Thomas.

So the America side of things really came together because of Nick and Joe. We were very much going to keep this UK-centric initially. It was a nice little thing that came out of this. And then this whole new generation of fans came along before we even found out he had a fan club in England while he was alive that we didn’t even know existed.

DP: And so that’s kind of how the film also developed naturally from a short. Because initially we just thought we’d make this a short, we felt like there’s no way we can fill 90 minutes, 75 minutes.

OH: We barely knew his life story at that point.

DP: Yeah. And then the more we discovered and the more people responded to it and were receptive to it, the more material we had. Eventually we were like, “This is a feature.” We had a three-hour cut at one point and we were like, “We’ve got to cut this down.”

I want to hear about the found footage film festivals because that is a new concept to me. It makes sense. Of course, people have been capturing things for their entire lives, whether it be on VHS camcorders, whether it be Super Eight, and now mobile phones. What is the intention behind the festivals? Is it to enjoy the work that people have done? There seems to be a balance of laughing at and laughing with the films.

OH: So we kind of have the holy trinity of found footage showcases, I suppose, in the film, Derrick Beckles is arguably the founding father of the modern found footage. He’s a little bit more out of that game now, he’s focused more on scripted stuff for adults. But he started off doing compilation tapes, these mashups of all these old infomercials he had taped off a shitty VCR and that kind of thing. He kind of led the path for the others.

But Nick and Joe are really more interested in — they track this stuff down or they’re given this stuff. They are a lot more interested in the context of the story than the likes of Beckles or Everything Is Terrible. They use this stuff in a more transformative way for mixed media performance arts and anarchistic stuff and collage work. They’re really interested in finding out who made this stuff and why. And that’s why they were immediately hooked on trying to help us find the story of Charles.

It unfurled when we spoke to people and found out more about his life. As you see in the film, my dad is the one who by accident turned us onto this footage that we hadn’t found in about a year and a half of production.

With a lot of people, we called them up out of the blue. We had everyone from a 90-year-old down in Cornwall to these guys in London, telling them “Hello, I don’t know if you remember this farmer, but 40 years into the present, would you like to be on camera to talk about this man you barely remember?” It’s been a bit hard to convince them and get them on camera until they’re comfortable, but it worked out.

DP: And I guess to add to that, I feel like our whole approach [was] the same as Nick and Joe’s. And that’s why it worked, we worked so well together. They were great to have on board as executive producers. Because the entire film is structured [as] the journey that we went on ourselves. At first you see this tape, you laugh at it, you’re like, “What is this? What am I looking at?” But then you become intrigued and you become interested and you really genuinely want to find out. That’s the journey we went on, and that’s the journey we want to take the audience on.

OH: I’m the only one who’s been able to see it on the big screen with an audience so far. And then it’s Dom’s turn, then it’s [producer Edward Lomas’ turn] at some point when we play the UK in the future, whenever that is.

DP: Well, we hope. (laughs)

OH: But everyone, every critic, every viewer, everyone who was in the film has watched it, everyone has got it. And they’ve got that we’ve tried to be very affectionate and celebratory. You have to lean into the idea of laughing at him in the content at the start, there’s no point trying to hide that. That’s why we constructed the intro like any generic sort of Netflix true crime doc to kind of lean into what people are assuming we’re setting out to do. And that may seem a little mean-spirited at first, but you kind of need to do that to then delve into this man and understand the emotional depths and all this stuff we were discovering.

We absolutely fell in love with him as a person and really admired everything he was doing as a carer as well as an artist who took this filmmaking deadly seriously when he was developing this stuff.

That’s one of the things which I felt as I was watching it. I realised about 15, 20 minutes into it that it’s a rare thing to have a film have you laughing out loud by yourself at home and enjoying what you’re watching. And then to have that feeling of the rug being pulled out from underneath you and getting to empathise and care and genuinely be moved by somebody’s story after having been on that journey. I found that such a really delicate balance, and you’ve all done it so well.

OH: Thank you. I would just like to give just so much credit to our incredible American editor, Hannah Christensen. We had previously worked with her on a documentary where it was a British subject and we brought in an American to get an outsider’s point of view. And again, she’s as American as they come. She’s from Milwaukee like me at the moment, and she just got this idea of British culture and this British eccentric, and made this into such a warm and kind film as opposed to if we had done it ourselves. We still had that intention. But she has this wonderful eye for really getting to the heart of this character of Charles.

This feels like an ode to the magic of creating. Charles is creating for himself, but he’s also creating for his neighbours, he’s creating for the people in the town that he’s living with. Is that an inspiration, the love for making films, for telling stories?

OH: Yes. You don’t spend four years of your life making a film if you don’t deeply care about the story and the people you’re responsible to portray in the correct light. Not just in a positive light, but in the accurate light and make sure that you’re not sugarcoating anything. Which we really didn’t. His story presented itself to us and we’ve portrayed that as accurately as possible without changing it up too much in terms of the editing and that kind of thing.

But Dom and I were making stupid little videos when we were kids with stupid little mini DV camcorders long before we met each other, put them up on YouTube in sort of 240p, 360p.

DP: Digital wasn’t even around.

OH: Exactly, yeah. And we were no different to what Charles was doing. A contemporary of Charles living in the same kind of area was Edgar Wright. We did try to get him in the film and he very graciously got back to us. He was just incredibly busy. Edgar Wright and Charles are making their fun little films at around the same time. Obviously, Edgar turned it into this remarkable career. If Charles had been able to stick at it with modern technologies, I don’t think we would have needed to step in and make a documentary. I think he would have done it himself. He came across as so enterprising.

And like you said, Andrew, he was making this for other people as much as himself including my grandfather, including locals who were in the film. It became very clear to us this had to be shown to people because he had designed it that way long before we ever kind of entered into his story after his passing.

DP: Oscar and myself [and Edward], the three creative core team of the film, we’ve known each other for what, nine years maybe now?

OH: It’s nine years.

DP: We met at university. And Oscar first told me and Ed about this film that he’s seen as a kid. And I was telling Ed, “I can’t believe what he’s telling us.” (laughs) And then eventually, [Oscar] found it and he set us down. I watched it in our room, jaw dropping, and I just couldn’t believe what I’d seen.

And it’s that same thing that Oscar was just saying. We were all making films when we were like 6, 7, 8 years old. I remember I actually had my granddad’s camcorder, and I edited like Charles did, combining two VCRs and pressing start and play on them to try to edit stuff together. And so you have this man who’s almost retired and who’s experiencing this and for the first time getting a hand at this technology and teaching himself. It’s impressive, what he’s been able to do with that as well.

There was the whole ethics point that we were thinking of first, like is this something that we should show the world? But then because he was handing it out to other people and he wanted it to be seen, we were kind of reassured that he would have been proud that people get to see his work.

OH: And that national competition — watching that is a Shyamalan level twist. I couldn’t believe that bit when I saw it. Because I was about to turn it off, “Oh he just taped over some old TV program.” And then that big reveal that he’s won that thing. That was even before we found this extra tape, and he had been submitting to these other magazines and had a fan club decades before we had started this thing.

Ethically, it became very obvious he was happy showing this stuff when he was making this for the villages and making these individual edits. That takes a hell of a lot of work. You don’t do that unless you really want other people to see it.

You guys are talking about making films as youngsters. [Charles became] a filmmaker at an older age and that is something that we don’t really get to see all too often. Did that readjust your mindset of who makes films or who can make films?

OH: I mean, we were looking for contemporaries. There’s a cult B movie filmmaker who we did interview. We had quite a few interviews that didn’t make the final cut for timing [or they] didn’t quite line up with other people. But David Rock Nelson, he was a character. There’s this fellow called Len Cella who made – he titled it Moron Movies. And he got on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson back in the 80s. Very US-centric. We couldn’t find anyone similar to Charles.

But yeah, when you’re looking at someone who takes this so seriously and does not come from a film-loving background — he had done photography but not filmmaking — it’s a hell of a lot more impressive. And his work still stands up. You watch that footage and eventually you are laughing with him and he’s crafting these jokes pretty damn well for someone who had never done this at a younger age, and with less accessible technologies than we had making our silly little films. Filmmakers now, they’ve got their phones, which we didn’t even have that point.

DP: One of the things that has stuck with me, as well is — I was shooting the interviews with Rob and Jake, the two guys from the Camcorder User Magazine. And back in the 90s, they ran this competition called the British amateur video awards. Both of them said they don’t remember any of the winners anymore, but Charles’ tapes stuck with them. They were telling us that even though it was the British amateur video awards, they would get some very technically well-made films. But Charles’ one is the only one that they remember 20, 25 years afterwards. That to me is testament that filmmaking as an art form isn’t just for professionals who are able to do this professionally with a big crew who’ve been trained or anything.

If you have a story to tell, if you are able to make people laugh, if you’re able to make people feel, make people happy or whatever emotions, then absolutely that’s what you should do, if that’s what you like.

OH: And what a shame it would have been to have just sat on this sort of oddity, as it initially was within my family and not show a document to changing English rural life and seeing this place that is very poorly represented within the British film industry and have it go nowhere and his work die out with the few people who were still around who he had given the tapes to. I’ll pass over to Dom because he was there for this soul-crushing moment. But it’s especially important we got this film and the little footage we have out there, because there’s not any of it left as far as I’m aware.

DP: Yeah, so because of the pandemic, I ended up shooting a lot of the UK interviews together with Ed because I was based in London at the time. When we interviewed Charlie Norman, Charles’ cousin — who actually was the one who introduced him to film. He got a camcorder and got Charles hooked on it. We had wrapped up, we had packed up the cameras, we’re about to head out and at the door, he said something like “Oh, it’s such a shame that you guys didn’t come two years ago. When I was moving house, we had about 200 of Charles’ tapes in the attic and I just threw it out because I didn’t have any more space for it in the new place.”

I said, “200? You had 200 of his tapes?” God knows what would have been on there. And we tried so hard to find as much of this material as we could. But yeah, it seems that it all disappeared.

OH: I am really hoping that when this film makes it to the UK, there happens to be some people who might watch it or stumble across it and they might have an extra tape. I think it’d be wonderful if this will bring out from the shadows some more of his work.

For you, Oscar, this film took on a mythic status in your mind over the years. What did that do to you, being able to tell these stories to your friends and being like, “Hey, as a kid, I got to watch this tape and this is what was on it”? What was that like?

OH: How do I describe this? It’s like when you finally get to scratch an itch. As you see in the documentary, I can recall it vividly, seeing the first half of that tape and then wondering what was on the second half that made my dad switch it off. When I recount that story, it’s really not playing up for camera. “Festered” is the wrong word, but it was always there at the back of my mind. What was on that tape? What happened to it? And this was long before I thought I could make a documentary of it. I was always curious what was on the rest of that tape? Because we’d lost it when we moved house a couple years after that initial viewing of it.

I wouldn’t really mention it to people just because I hadn’t seen the whole thing. I mentioned it to Dom and Ed because we work so closely and they love film and they love outsider art and outsider cinema as much as I do. But yeah, finally getting that tape from my aunt, her copy, blew my mind wide open, essentially.

None of us had ever planned to get into the documentary game. I love that particular medium, but I feel you need to have a very specific skill set. And I developed it elsewhere with more scripted stuff. All three of us had worked around short films. Dom has worked for these huge Hollywood blockbusters. It never crossed our mind to make a documentary. This story fell right back into my lap, and they were the first two I showed it to. This is how well we work together, they both immediately went, “We’ve got to tell the story.”

DP: Oscar, you told us about the story at one point and then all of a sudden, you were like, “Guys, you can’t believe it. My aunt found the tape.” I think we were all living at different places: I was in London, Ed was – I think you were back in Bristol or something.

OH: You were still in London.

DP: And you came over to London and you were like, “You’ve got to watch this.” I was like, “All right, all right.”

Did you put it on as soon as you found it, Oscar? Or did you wait to get an audience to watch it together?

OH: No. Drove home and I watched it immediately. Because for all I know, it’s not going to be anything special. When you’re a kid and you have certain memories, you do tend to colour it and rose-tinted spectacles and all that kind of thing. But yeah, it was that first viewing. And I really do envy people who sit down and go in blind for the first time. That’s been wonderful about the live screenings. You two will find this. Not to hype up the film or anything, but you two will experience that audience reaction to the first time you watch this stuff as it gets gradually more odd. It was remarkable. I will very vividly recall that for the rest of my life, that initial full viewing of the whole thing.

Charles’ story is both life-affirming and death-affirming. Did your perspectives on life and death change as you were telling his story?

DP: You know, at first the death moments are the shocking bits of the tape. That’s the part where you can’t believe what you’re seeing. But then, as you watch it more, and as you kind of understand what he’s doing, the whole aspect of death positivity that we’re addressing in the film is something that none of us were aware before we were looking at it. I think all of us have grown in our sense that his perception of life and death and the lifecycle is obviously very much deriving from his life as a farmer, because you deal with that on a daily basis. Animals die, animals are being born, and it becomes normal to you, it becomes part of life. It is normal. But you know, death has become such a taboo that what he was doing on tape seems strange to most people. Watching this, I think you start to understand what he’s doing, that he wants to memorialise. He wants to celebrate his cats, his parents, and all these people that he loves. I think that has affected all of us in a way.

OH: It was actually one of Nick and Joe’s fanbase who made us aware of this concept of death positively. I’d never heard of it before. It’s obviously a newer thing. And we start to dig into it and it absolutely makes sense that Charles was ahead of his time and a pioneer in this long before it was a concept that he would have even known. And we got turned on by Joe to Thomas Lynch who is a very famous mortician and poet. His work was the initial inspiration for the HBO show Six Feet Under.

So I went out to the Upper Peninsula in Michigan to interview him in his home. It was really enlightening. He’s out of the mortician game at this point. I had always planned initially to be cremated, but having spoken with him, it really kind of turned me on to a lot of the positives of being buried. It’s this idea of, as Dom says, memorial. You’re dead either way, it doesn’t matter what happens with the remains, you’re not on this earth anymore, whether you’re in the ground in a pot somewhere or you’re somewhere out there, depending on what you believe.

But this idea of cremation feels a lot more disposable, as though right, we’re just getting rid of this person and moving straight on. It’s all very impersonal and, in Thomas’ opinion, slightly disrespectful to the person whose life was lived and the people that they’ve touched and affected and that kind of thing. So this film has directly impacted an element of my life, you might say the end of my life,

When the film heads out into the world, does that give you a bit of hope or excitement about having people’s notions about death challenged?

OH: No, it does. And I’ve said this before: I would rather have one person be affected by this in a very positive way than have a screening room of a thousand people love it but not really take anything from beyond just “This guy’s stuff is crazy.” When we set out with this, we never thought there would be these open and honest conversations about life and death.

The other big thing that really came through [was] the more we spoke to other local farmers and looked more into Charles’ life story is this idea of specifically rural mental health and the strain that farmers are put under. It became this really important linchpin of the entire thing. Charles was like a lot of farmers who — he gave up a life up in the north of England in a lucrative career of lecturing and teaching at a very prominent agricultural college to go home and care for the family farm. And that’s what generations had done. That’s becoming less and less common as you’re getting more automated machinery. The younger farmers’ kids are not as inclined to run the family farm anymore, so you have a lot of people in isolation. I’m really hoping that for people in rural areas who might watch this, it really opens up discussions of considering their mental health and the pressures that they’re under.

I think that’s a really great point as well. Charles’s neighbour was talking about the interactions that he would have. He would say that Charles is out and about, he would see Charles is out about with the cows. But the interaction is merely a visual, not an actual connection. And that felt like a really, really important thing: to have that connection, to go on knock on someone’s door and see how they’re going, to share stories, to share their life with one another. That was a really important thing.

DP: And that’s kind of what Charles did. He knocked on their door, gave them the tape, and then he came back a week later and asked them (laughs)

OH: Made sure they’ve watched three hours of a tape. Yeah.

DP: Even though we’re more connected than ever with the internet, with social media, we are still arguably less connected on a less personal level. He kind of pioneered like a Facebook story or something like that is, but he made it more personal. He actually went to the people and he handed them the tape and he had a conversation about it afterwards as well. I think it’s so much stronger than anyone on their phone taking the story and putting out on Facebook.

OH: And I think people now get him a lot more than people did at the time, including people who were very fond of him who are in the film. He’s a little bit odd and making these odd little films for the few people in this rural village. But people now, they get what he was doing, they get death positivity as an idea.

Last question for you both: what is your favourite Charles clip?

DP: I’ve got two and they’re pretty close competitors. They’re both from the tape that he sent to the baler which is the skeleton race on the cow, and a skeleton losing weight, because they just made me laugh so hard. I just couldn’t stop laughing. And that’s what I remember most. Every time I see these clips, I just can’t help [laughing]. And that’s what he wanted to do. That’s what he wanted to achieve.

OH: For me, it’s sort of between two. On a sentimental level, it’s obviously the footage that he shot of my grandmother who was the district nurse. She passed away before I was born. So you know, it’s the only record I have of her. But the single most entertaining bit, I actually love the little short film he made where there’s a narrative [and] he’s doing his own stunts. He’s the policeman talking to himself as a skeleton. And God says, “Oh, because you haven’t got anything to do up here and you’re bored, go down and mow the lawn.” He made a short film. And it’s probably my favourite thing he did out of all that footage.