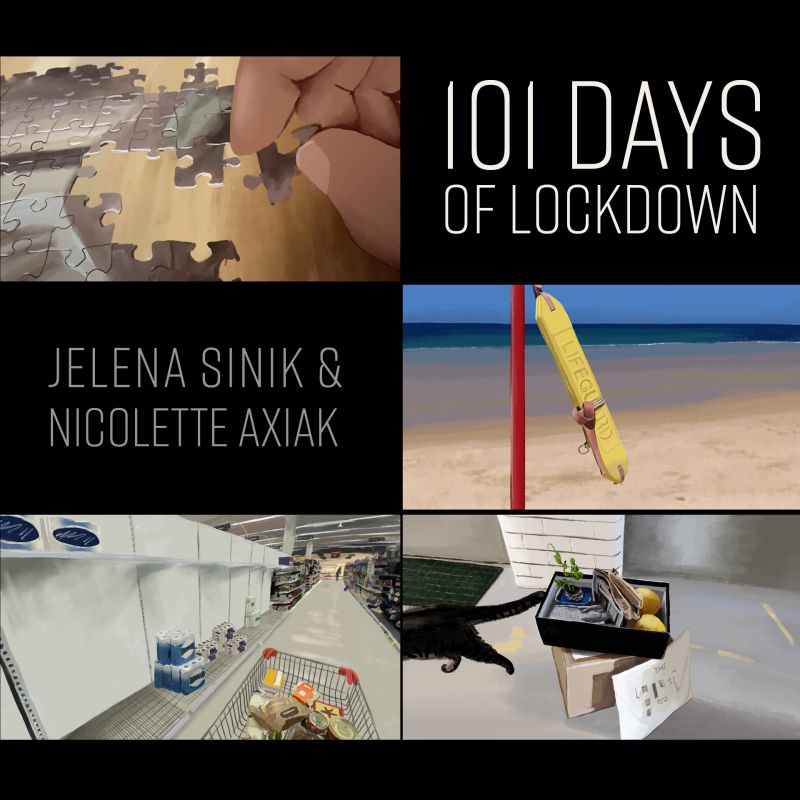

Within the space of almost two minutes, Jelena Sinik and Nicolette Axiak take viewers on an emotional journey of the impact of isolation in their powerful animated short film 101 Days of Lockdown, which makes its world debut at the Sydney Underground Film Festival. Made as a reaction to their personal experiences of being in COVID lockdown NSW, the two close friends who live 40km apart share digital postcards of their daily activities, ranging from the cup of tea they made, or the limited outings in their five kilometre radius to get toilet paper.

The talent and passion that both Jelena and Nicolette have for animation and art is clear in the film itself, with Nicolette providing the score to the film. That passion and enthusiasm for each other spills over in this interview where the two friends talk at length about their working relationship, the importance of animation for each other, and more.

I’m continually amazed at the emotional depth that filmmakers can bring to the realm of short films, and even more stunned by the brilliance of animated short filmmakers, with 101 Days of Lockdown utilising that brevity to amplify the space of time that much of the world experienced during COVID lockdowns. While my experience of a lockdown is vastly different than what NSW and Victoria went through, I found an enormous amount to relate to within the film. I cannot wait to see what Jelena and Nicolette produce as animators going forward, their voice is refreshing, vital, and most importantly, full of warmth for each other and the energy that storytelling creates.

The Sydney Underground Film Festival runs from September 8-11, with 101 Days of Lockdown screening as part of the Aussie shorts line-up on Saturday September 10. Tickets can be purchase here.

This interview has been edited for clarity purposes.

There is a brevity to the film, but it carries so much weight and emotion. The time has gone so by so quickly that it feels like it never happened at all, in some ways. Is that the vibe that you were going forward with the film?

Jelena Sinik: You’re totally right about that. It’s this really strange time when you think about it. 101 days is a significant amount of time. And it is something that nobody really talks about anymore. But it was always talked about day in and day out every minute of every day. The idea was that we would explore this rapid insight, quickly, through this sort of long, repetitive experience. We constrained the shots to one second per day, so we focused on a highlight or lowlight of a day.

We kind of coined this term of ‘the disposable memory’, because so little significant experience happened during that time, that would be deemed noteworthy or something that you could kind of commit to memory. Nobody really remembers making a cup of tea on a Wednesday, but that seems to be something that we had to focus on at the time. So these sort of banal experiences became fixtures of the lockdown experience for us. We wanted to look into these ‘postcards’ of a time where we didn’t travel, and we were all committed to stay home. So that’s kind of the feeling wanted to go for there.

I understand that you both live about 40 kilometres away from each other. How long have you two been friends for?

Nicolette Axiak: Probably about four years, I’d say. We met right at the end of university. Both of us were right on the tail end, doing a Masters post grad degree and just started chatting in a university lab and just became best friends after that.

JS: We did yeah. We’re very different people with very different styles, but I think we share significant values in life. Our friendships one that’s gonna last, I’m certain about it. We do live 40 kilometres away. We were we went to the University in the city, which sort of centralised us, so we were able to spend time together and see each other.

My personal experience is that I live alone, and Nicolette at the time of the lockdown lived with family, so we had very different experiences in that regard. And, being in the east and west of New South Wales and of the city made a big difference too, because I’m within five kilometres of the beach, I could go swimming every day, and that’s something that I do, but for Nicolette it was a very different experience, right?

NA: The thing about the west is people kind of moved there to be around big families. There’s a lot of space, it’s very suburban. And I think that during the lockdown when the film is set, a lot of that was taken away or it just really shifted the focus because you kind of had to build a community around the people that you lived with, if you lived with people. So a part of the story is just reflecting on what it was like to be in a place where community is so fundamental, but you’re not able to interact with it in the way that you normally would.

Coming back to what you were saying before Jelena, it’s like we almost don’t talk about that it happened. And there was this push to move on past it and kind of leave it in the past. But it is a huge thing that happened in part of our lives. And getting to see it in this way is really quite beautiful, because it is very grounded in a lot of ways. How did you go about creating and deciding the shots?

JS: It is 100% a true story, so nothing’s made up in that experience. I mean, what would really be the point of that? We recorded stuff, we observed things. It was kind of like a search for what was meaningful for us in a day. And it seems a bit sad that this is what it amounted to. But I think our experiences were quite singular, we experienced different things. We went with what was organic for us, like we didn’t really want to create a specific narrative. We wanted to explore that experimental space. So particularly Nicolette, like your experience is quite domestic, wasn’t it?

NA: Absolutely, and you really can see the divide in the film, there’s a left and right screen. So everything that’s on the left side is the story of the west, everything that’s on the right is the east, so there is actually a dialogue between the two. There are moments when the stories overlap, there are times when they’re in solidarity. That’s kind of how we built the film, so that there is a very distinct dialogue between the two.

JS: And there is a sense of distance in the fact that they are separate screens. It is kind of like a diary, so we’re trying to diarise an experience as truthfully as possible and with the integrity of what actually happened. And of course, with a kind of a stream of consciousness feeling. Things that we committed to memory that we now look back at and think “Gosh, that was 101 days.” It’s a hugely significant amount of time. And I mean, the lockdown was a little longer than that, but when you clock over 100, it’s meaningless, senseless, it doesn’t matter how many days. It was a long time.

I live in in WA, so my perspective of what a lockdown is, is very different than what New South Wales and Victoria went through because our lockdown was just ‘nobody can come into the state’ and we were able to carry on our lives. And it was a bizarre feeling, because we will be able to look across over east and people are just trapped in their homes.

JS: You’re absolutely right. Your experience I’m sure had its own difficulties. I mean, we’re all on an island, right? So we all had our own difficulties. I can’t imagine what that would have been like not being able to have people come in and out. It must have been a very specific feeling for you guys. For us, it’s crazy, really, that that’s how we had to live. Everything stood still for a while, we only really had a sense of the now. I couldn’t see the future. I couldn’t know what the future was holding. I had no concept of it. And I’m not like that. I’m a very forward-thinking person. So we did feel trapped.

I think it was very different particularly for Nicolette, because she had the police curfews. The west was under a different kind of scrutiny than the eastern suburbs. So that was very particular to you, we focus a little bit on that in the Nicolette side of the story, too.

NA: As different as the experiences were, there is a universality about them to really. We kind of wanted to make a documentary, so we wanted to take the experience and build something that had this very strong effect on a very strange time in everyone’s life. Everyone in Australia in some way experienced what we’ve put forward to them, so hopefully people can watch it and empathise with certain shots and sequences and feelings that we felt. We just wanted to remind people and just recreate some feelings that they had.

JS: We [made] the shots a second long because we wanted them to have the constraint of what we felt. We wanted it to be a limited time. In the same way as we felt limited by our ability to move. We had a five-kilometre radius, I couldn’t move past that. There were people I wanted to see who couldn’t visit me, no one could come over my house. There were days where I didn’t even verbally speak with someone or use my language. Because I live alone, if I didn’t have a phone call that day, I didn’t speak to anyone.

I feel like the point of making this film for us – because we’re both artists, and all filmmakers are artists, film is [an artform] – I feel it was to make something during a period where there was very little focus on connection in a universal sense. We really wanted to connect with people. And we wanted people to watch this and think, while our internal worlds are so complex and different as individuals, and our own experiences are going to be different, our physical experience was not that different. I mean, I’m sure while you’re in Western Australia, you also felt there were things you couldn’t do. And I think it’s just that lack of choice. It’s having that freedom taken from you, in whatever form. I think we all experienced that in different ways.

NA: Historically, we could have never imagined a time where you were unable to travel outside of five kilometres from where you live. It’s just a really strange time. We just really wanted to create a little snapshot of this particular time in history. I like to call them ‘little postcards’, I think it’s a really nice way to encapsulate kind of a feeling that we’ve created. It’s just like a little glimpses of like, “Oh, we were here,” just a little bit.

JS: They are digital postcards. I think about the multitude of media at the time, we took so many photos that we sent to family and friends and said, “Look at my cat.” “Look at my garden.” “Look at my tea.” “I cooked this today.” And we sent so many of them. They’re kind of our digital postcards. Our film is based on the things that we decided were memorable and were worthy of sharing. And when you look back at them, they’re kind of silly in a way.

We’re glad we found the motivation to make this because it [was] very difficult, as you know, for creatives during that period to produce things because you don’t know what the world is going to be like, and whether you’ll be able to do that stuff again. There was a lot of uncertainty there.

Who initiated the conversation? Was it just an organic discussion to be like, “Hey, let’s create this project together and tell this story about our experiences together?”

NA: Jelena was the director of the film. She kind of was very much the pioneer driving force behind what you see. But she certainly invited me in. A lot of what you see is just a dialogue between us.

JS: The films that Nicolette and I collaborate on are very much Nicolette and I films. They’re films that come from our friendship, because I think as artists, we react to the world. Every day we respond to so much stuff all the time. And we were just responding to a period where we felt like we needed to create something together. Because we couldn’t see each other we couldn’t meet, we couldn’t talk, we couldn’t go for a walk in the park, we couldn’t have dinner together, all the normal things that people need to have a human connection. So we felt this need to just produce something, to make something together, to be generative. And I think that’s where that film came from.

While I may have directed, it is very much the both of us. It’s us looking for a way to bring our friendship together to create something that we’re going to look back at years from now and think, while our experiences were incredibly separate, we were there for each other every day. As a collective society, we did try to be there for each other. And I find that that is the positive that came out of lockdown. It’s this beautiful thing that you can be generative. You can look back at a time and see that you were really supportive in ways that may seem small, but they made all the difference for us.

I’m curious about the desire to explore very personal things through animation, which obviously is not a traditionally child focused or kid focused medium, but there is a public consciousness that believes that animation is exclusively for kids. Is that desire to explore the personal also a way of challenging what the notion of animation can be?

NA: For me, a lot of the art that I create is just purely driven by observation. Things that are important to me, things that I grew up with, things that I’ve observed. I think that you’re absolutely right, while [animation] can be seen as something that’s targeted towards children, there’s so much that you can do in animation that you just can’t in live action. For instance, the biggest thing for me is fundamentally the fact that when you’re the animator, you get to be the director, the producer, the writer, you can build the whole pipeline. And then you can bring people in, Jelena and I love to collaborate both as animators but also as filmmakers. There’s just something so wonderful about being able to produce an entire film by yourself.

And there’s nice fluidity that you get through animation. There’s ways that people can project themselves onto an animated character in the way that they can’t on a live action character. You can see yourself in the artwork in a very different way. You can control the motion of the character. The way that a character moves fluidly is totally in the hands of the artists that’s creating it. There’s so much control that animation gives you. And by control, I really mean freedom. There’s something so beautiful in the way that you can direct a character that’s being driven by your own hands.

For me, it’s something that I really was drawn to when I was studying animation. I’m like, “Oh, wow, I can control this process. I can express myself in this character. I can build a narrative around what I want this person to be doing.” And a big part of that is just observing the world and thinking “How is this character going to move in the world that I’ve created for them?” There’s just something really nice about having that control or freedom.

JS: I think as animators or as filmmakers, we always want to tell stories that we understand, stories that are personal to us. There’s no sense in making a story where you don’t have your own point of view. And that’s what this film is for us. While we don’t have a clear character, the film is animated from our perspective, it’s completely our point of view. This animation feels like a film, you’re not looking at it for just its animated value, you’re looking at it as a story and as a cinematic experience, and what we like about animation is that it cuts the noise away. It really lets you take what a film would record fully and if you remove things, you paint the parts you want to focus on that express emotion.

What’s your collaborative process like?

JS: For this specific film, what we did is we had our own stories. Nicolette had full control of what she wanted to say about the western suburbs and her input on that was purely hers. And then, on my side, I had my own story. And I guess the magic happens where we know each other so well, because we’re such close friends that we understand are each other’s intentions and the kind of the things that are important to us. So seeing the shots that Nicolette was coming up with, as we went along, we crafted that into a story. It was very organic, it wasn’t like “We’re going to do ABCDEF and we’re going to structure this many shots and that many shots.” It was the highlight of everyday for us to sit down and make a little thing and then go “Oh my God, look, I did this one.” “ Oh my god, that’s amazing.” And that’s how we did it. We did it for each other and for everybody else and it was an organic process. Wouldn’t you agree with that, Nic?

NA: As much as the film is a dialogue, the process was a dialogue as well. It was just a conversation producing each shot where we’re just like, “Okay, well, this is the back and forth.” There was a really beautiful cohesion through this process where both of us were laying down ideas and shots and finding ways to marry them together. And the result was what you see before you.

JS: While I may have sort of pushed us and said, “Hey, let’s make this into a film. Let’s constrain it to a second. Let’s do this structure,” Nicolette very much brought her point of view to that. And that’s super important to say because she’s is equally as valuable in this process as I am, because animation is like that, but the roles melt a little bit into each other. It’s not quite as clear cut as you might think, on perhaps a team of people working on a film.

Let’s go back to the beginning, what was that kernel that kicked off your interest in animation?

JS: I started off studying film, my undergraduate degree was in film. And I did my Masters in animation. So did Nicolette. My desire to get into animation came from this idea of being able to produce things that were metaphorical in a way that I didn’t find film could provide me with. And I know that film is a highly conceptual metaphorical space, but there is something really special about using your hands to create something, to produce something. And there is a joy in movement, there is a joy in being able to show something to someone that you purely created on your own.

It’s all about story for me. I personally am interested in experimental filmmaking and experimental animation, or utilising both animation or hybrid animation and film. Taking a narrative and then breaking it, and showing people things in unexpected ways, for me is where that excitement happens. It’s kind of like magical realism, it’s being able to capture things and add things and really layer on levels of meaning and ways that people can observe things. That’s kind of what got me excited about it.

I fell in love with film. I always wanted to be a director to begin with. And then I found, like Nicolette mentioned, this ability to be able to control things in a level that was so personal to me. And that really helped me look into animation further, because there is some amazing surreal animation. People always think animation is for kids like, like you said they do. I remember saying once “I’m doing a Master of Animation,” and someone said to me, “What? A master of cartoons? They do that?” And it’s funny but people don’t understand how much of an emotional medium animation is. And it’s been around for a very long time. And it’s something that people have experimented with, certainly. I find that it is in an experimental format really special.

NA: My experience was actually quite different. I had just come straight out of school and into animation thinking like, “Oh, I love to draw.” It was my favourite thing to do, to just fill sketchbooks day after day, just drawing pictures. And I realised through learning about what animation truly is that it’s so much more than that. It’s about telling stories. It’s about putting emotion into a character. And for me, that was actually the part that I fell in love with, the ability to build a story.

Jelena and I do have very different things that we gravitate towards in our storytelling, like I tend to be more linear conventional in my narratives, but through collaborating with Jelena, she’s really expanded the way that I think about film as a medium. Like she’s saying she breaks the narrative, now I can think, “Ah, what’s the way that I can set up an expectation with this film and then distort it and find new ways to encourage the audience to feel something different than I would have otherwise created.” It was just really a love of drawing that got me into it, and it was a love of storytelling that kept me here.

JS: It’s really amazing to be able to visualise things. We like to think of animation like visual poetry. It’s this amazing space that is magical, and you can write a story and really bring it to life in a way that I think no other medium can. So we both share that love.