It’s not hyperbole to say I’m a little bit obsessed with the new Courtney Barnett documentary Anonymous Club. Directed by Barnett’s friend Danny Cohen, this is not your typical music-doc, with Barnett letting her thoughts and emotions out on a dictaphone which she sends back to Danny to edit in with grainy footage of her on tour, at home, living her life.

In this interview, Danny talks about the editing process and finding the narrative of Anonymous Club, what it’s like to shoot on film while on tour, the realm of being vulnerable for an invisible audience, and of course, we had to touch on that Jimmy Barnes meme, which Danny directed the music video for.

Anonymous Club is in Australian cinemas from March 17th, with Courtney touring Australia in support of her new album Things Take Time, Take Time.

Find out where Anonymous Club is screening here.

This was my most anticipated film of the year. I was sitting there, eagerly waiting for it to come out, and it’s just so great. I love it to bits.

Danny Cohen: Fantastic. Thanks so much. Very, very sweet of you. Are you a Courtney fan?

Yes, I am. Yeah, beyond a doubt. Gosh, I can’t even remember the first time that I saw it was probably at the Astor here in Perth, supporting Something for Kate for the Star-Crossed Cities Tour.

DC: Wow, cool.

Way back when so almost ten years ago. And her music has become part of my life in a way that has been a little bit unexpected. It was very emotional watching this film, because it’s the exact kind of documentary that I expected about Courtney Barnett. It’s not your ‘sit-down talk’ kind of thing. Which is just so brilliant.

DC: Oh, that’s good. That’s a relief.

I did an interview with Sue Maslin just the other week in the lead up to the documentary conference, and we were talking about Anonymous Club, and it was just so comforting because I was coming at it from a point of view as a fan, and she was coming as the point of view as somebody who’d never really heard Courtney’s music before. She was very much like, “I’m now a fan. I’m now on board.” So it’s really comforting.

DC: I’ve been getting a lot of that. People have been saying they didn’t know her music or they kind of knew her music, but then at the end, they like wanted to be her friend. I keep passing all that sort of stuff to Courtney. That’s what it’s about. Partly, I think she’s more nervous for it to come out than I am. I’m really proud of it. I think we made something really special. And yet it almost killed me. And I’m just excited that it’s done. It was such a journey to spend so long on something like that, and then to figure out how to tell a story with just the dictaphone and with the footage, it was just such a difficult process. And so I’m kind of like if people don’t like it, great. If some people like it, that’s how it goes. That’s good art, I guess.

There is something comforting about being receptive to things that other people aren’t receptive to. I don’t know if it’s a comfort for Courtney at all, but it feels like it might be, that she’s speaking to a specific group of people. Which is something I felt from the film, that she’s speaking to certain groups of people and it works so well. I don’t know if you can speak to that at all.

DC: I don’t know, I haven’t really picked up on it in that way. I mean, I don’t think so. I mean, she knows who she’s talking to. I think she forgets that it’s me that she’s talking to. It’s an easy entry point to be like, “Hey Danny,” and at least it gives you that confidence that you’re talking to somebody. Because it’s really difficult to just talk in a room and hear your thoughts out loud. It’s really strange.

I did it a bit to give to Courtney. And it’s just like so nerve-wracking to do that with anybody. Because there’s no two way, it’s just one way. Even if you just talk about your day and the feelings that came up and down, it’s quite intense. So I think when she was doing it, I don’t know if it was initially cathartic. But maybe it turned into something cathartic, or just a way to check in with herself and see where she’s at with things. But more often than not, I guess you’d only pick it up when you’ve got something to talk about probably negatively.

(You’re) less likely to pick it up and be like “Today was so great, this happened, this happened, this happened.” You’re kind of doing something else if you’re in that mood. But if you’re kind of solemn or you’ve had a rough day or something’s on your mind, it’s more likely that you want to reach out to somebody in whatever facet that is, even if it’s just a diary. I’ve never really spoken to Courtney about how she felt, if it was cathartic, or what she got out of that process. I’d be quite curious. To answer your question, I’m not sure.

How did you feel? Regardless of whether there was going to be a film or not, just being there, the receptacle for receiving how Courtney was feeling at that particular point of time. How was that for you as a friend?

DC: I was really touched and honoured. It was lovely that she put that much trust in me as a friend and as a filmmaker. But it was difficult because I saw a side of Courtney that I never knew was there. We were good friends and we’d hang out here and there, but I don’t think we’d ever really dive in that deeply in how we felt about everything. We’d talk about the creative process a lot, I think that’s something we bonded over. But we never go that deep.

And so when I got the first round of dictaphone entries back, I was like, “Oh, okay. Holy shit. She’s being brave and she’s going for it.” Because the Courtney I knew from having worked with her and stuff, she’s naturally shy and all that sort of stuff. Which is fine. Everyone is, depending on who they’re talking to. So I was really floored by how open she had been and how much she gave to the dictaphone from the get go. I was just like, “Okay, this is good. She trusts me. Like, we’re digging deeper, we’re gonna find something here. I know what it is.”

It took a long time for me to figure out what the film’s about. But it was weird from a friendship point of view because I’d be getting a dictaphone every couple of months and backing it up, and then I’d hear something, you know, a particularly fragile moment. And then I’d be like next time I see her, “Hey, so are you all right with that thing?” And she’s like “Oh. What? No, that was two months ago.” [I thought] oh okay, maybe I shouldn’t bring stuff up. Because the film or that device and our friendship crosses over in such a weird way. It’s very strange.

I think that Courtney has this real vulnerability in her music. There’s this openness in music, and that’s what makes it so easy to accept and easy to approach. And that vulnerability is obviously in the film too. And for me, I think it’s really brilliant that you open with the awkwardness of that interview to start off, that interview of being asked “Presenting anxiety in your music – how do you deal with that?” And it’s like, “I don’t know.” It really sets the example of why you’ve chosen this particular way of presenting her story in film. How did you find the right tone of presenting that vulnerability, presenting her vulnerability in the film itself?

DC: That’s a good question. I know that from the get go, we needed to make sure that people were on the journey with her. Not that they would be against her, but the people that didn’t know her, they could understand this situation she’s in, the position she’s in, both with fame but then also with how she’s feeling and her confusion. I feel like you have got to set that from the outset where people can relate to her. Well, she is. She’s very relatable and down to earth. So I think with someone like her, she’s being that open, then you can connect.

I think from the outset, it was always about trying to ensure that Courtney didn’t feel like she was, for lack of a better word, whinging about her position. It was really important to get over that hurdle. Because it’s quite draining. “Okay, is this what the whole film is going to be?” There’s only so much you can hold an audience (with) before they’re like, “Man, I feel so sorry for this person. I just feel depressed. It’s too much.” But we were just trying to strike a balance, wanting people to understand what she’s going through.

There are those lines where she’s like, “You know, I really want to do this tour, but I don’t want to do this tour. And I don’t know why.” I think even by saying, “I don’t know why,” that helps the audience be like, “Okay well, she’s not saying ‘I don’t want to do this tour because x, y, and z is hard or whatever,’ and ‘I’m nervous,’ all that sort of stuff.” She’s like, “I don’t know, I can’t figure it out.” And so the audience is like “Okay, will she figure it out, what she’s looking for, or how she’ll get past it?”

It’s fascinating, especially for a lot of the tours that she did around Australia at the time. These were ones that I had gone to seen her live at, and getting to see her live, I’m like, “Ah, I’ve now got a context for why the gig was the way it was or why she played a song the way it was.” That’s what I’ve really found quite enjoyable and exciting about Courtney’s music, one gig will be very different from the next. She’ll play one song quite angry, or the next time that you see her, she’ll play City Looks Pretty a little bit more subdued than usual. And it really leans into how she’s feeling at that time, her emotions at the time.

Certainly as a fan, it helps contextualise things, but throughout the film, you get an idea of how she presents her mood, her emotion throughout her music. And that I thought was really quite brilliant and presented in a way that as a director, you’re not actually saying to the audience, “This is how she’s feeling right now.” It’s just letting you into her space in a really comfortable way. This is, of course, your first feature film, how did you find your way throughout telling this kind of story? How did you make sure that you were hitting the right tone, hitting the right beats?

DC: Good question. Partly intuition, partly endless advice from filmmaker friends and just friends in general. You know, Glendyn Ivin was our story consultant. We’re at the same production company, we’re at Exit Films together. Same with Garth Davis as well. So there’s people around me that are quite supportive from a narrative sense.

And I always wanted to frame it like a narrative. It’s obviously a documentary, but it does still feel like it could be a three-act narrative film, like a drama, it’s almost there. I’m not an avid documentary fan, and I never thought I’d be making one, but the opportunity presented itself and here I am. I tried not to watch a lot of documentaries going into it too. Because I just didn’t want to be like, “Oh, that’s good” and naturally, I’d just get influenced by it and all of a sudden, you’re just making that.

I’ve looked at Don’t Look Back. That’s what we set out [to do]. I was like, “Okay, if I’m just like in the corner of a greenroom, just doing my thing, documenting, we’ll find a story, we’ll figure out what that story is.” It’s such a hard one. Because so many things influence you and funnel through that come out in creative ways. But just a really a lot of support around me and people to bounce ideas off and all that sort of stuff. I just was trying to really make it as slow and meditative as I possibly could without it feeling dry or boring.

How long did you shoot for?

DC: Three years on and off. I was gonna say, when we started the edit, I showed the editor Tokyo-ga (1985), the Wim Wenders film which is about him going to Japan and he’s interviewing people that worked with [Yasujiro] Osu. It’s so observational and poetic and slow, and it creates such a feeling. I remember the first cut we did, it was so long. You can see in the film there are certain types of framing that I’m into. We got some feedback from some people that came in and they were like, “It’s a long film, like it felt really long.” And it’s like “Okay, maybe I can’t get away with that sort of stuff without reason”, not just for the sake of it slowing down.

I’m a big fan of slow cinema, so I’m like let’s just hang out with the film for a while. But I think it’s different in this format, where I’m just using story based off a dictaphone. There’s no script, no talking heads. So it may be a little bit more difficult to do so.

I’m a huge fan of slow cinema myself. Drive My Car was fantastic, and I love Kelly Reichardt. I like that meditative stuff that just carries you on a journey and takes its time. Who are the filmmakers who you look to as an inspiration for that kind of that cinematic language?

DC: It’s hard because it’s not particular filmmakers because everyone has their own sort of flair. But it’s hard because with this film, I wasn’t really referencing anything but other than Tokyo-ga. But even stuff like First Reformed which is kind of like a Bresson-like world, anyway… I was talking to someone earlier today about Eric Rohmer where I was like it’s not slow but it’s very talky and you can just sit in a scene for ages and people just chatting away, chatting away and it’s fine. Like Bela Tarr. I don’t seek it out. But when I watch it, I’m like sure, let’s do it.

What was that great Korean thriller a couple of years ago? Burning. People were like “Oh, it was so slow.” I was like, “Nah, that’s not slow. Everything had its place.” I don’t think I’m one of those [people who are] like “Slow cinema, that’s all I have to watch.” We watched Satantango in the cinema which was awesome. That just flew by. It felt like four hours maybe, there were intermissions. But I think there’s something really special about just sitting there, and it’s slow enough that you can reflect on your own things, your own world, or you can kind of go off on a tangent, but you’re not lost in the story. It’s kind of like a conversation. You’re not rushed. And you’ve got time to process things and daydream. It’s something very special about that sort of style.

It gives your mind the space to kind of be free a little bit, and to be a little bit loose. So are you out on the road filming all this while Courtney’s on tour, or you were at home and there were people capturing footage while out on tour?

DC: It’s just me, there wasn’t anyone else in the crew. And that was on tour and at home or back in Australia. So I did sound, DP, film loader or whatever, all the all the fun jobs.

All the technical stuff. So in between gigs, in between filming, what are you doing? Are you catching up on rushes, having a look over what you’ve shot throughout the day? Or having downtime with the band, with Courtney?

DC: On tour, it’s so fast moving that there’s no time to sit and reflect. Every day is somewhere else, especially when you’re doing the European tours or America tours where you’re on the bus. It’s pretty much unload in the morning when you’re in a new city. I’ll be trying to figure out what Courtney is going to do that day and tag along. Could be press, could be just hanging out in a hotel, then do the rehearsal, then there’s dinner, then there’s a show, and you’re back on the bus. And then you drive through the night. And then the whole thing happens again. Now I’m in Paris, now I’m in Belgium. It’s just crazy.

And you don’t have any real alone time. I was saying to Courtney it’s only once you close your little bunk curtain that no one’s around. I can just have a sleep, I can just read, sit on my phone, whatever it is. It’s just like your own zone. So there wasn’t much time to do any work when I was away. There would be sometimes a couple of days off here and there, but I wasn’t editing or anything like that. And the film takes so long to get to New York and for the rushes to be uploaded or shipped back to me on a hard drive. So it was like every few months, I’d get that footage back and just hope it was one) processed well and there’s actually pictures; and two) that there’s decent pictures.

I imagine there’s got to be a bit tense, sitting there waiting. That waiting period.

DC: It was at the beginning because I hadn’t shot film on my own, I always had a DP. And so loading I was very particular about – but I was a projectionist when I was in my teens or early twenties – so I understand how film travels around, so I was quite careful. I was like, “This has to be kept in the fridge.” There are so many rules to it. And then by the end, I’m just like “Chuck it in the boot. It’s fine.” You know, it just works. Obviously, if it was a proper narrative feature film, you might be a little different with it. But I was like, “I can’t play this game like that.” It went through a bunch of X-rays, it’s fine. Like it’s really, really hardy.

What type of film did you shoot on? I’m so used to people shooting on digital and looking back at the rushes going, “Oh look what we’ve done today” kind of thing. It feels like a rarity to shoot on film. What did you shoot on? And what was the decision to shoot on film?

DC: We shot on Kodak Vision3 500T. They’re like higher ISO tungsten film, the whole thing was on the one stock. The decision was because it’s the look. I feel it’s more immersive. It’s got a natural quality to it. It’s textural, it feels alive in a way and it’s softer. It doesn’t have that same artificial feeling that digital has. I don’t think it’s a debate, digital versus film. I think they’re just different worlds. And that’s fine. But I think digital is quite sharp and – not in an insulting way – sterile, very clinical. Obviously, so many beautiful films are shot on digital.

Also it came down to like a happy accident, how much I was rolling as well. I was rolling like a roll a day, like ten, eleven minutes a day on film. Whereas I know on digital, I’d just be like five hours. Because you would, like why not? You’re there and that’s your job. And then by the end, you’d have 500 hours’ worth of footage which is just like impossible – well not impossible, just so difficult to go through and find those moments. And also I think there was something about being in greenrooms and stuff like that and not having a little viewfinder, and people can see when you’re filming. There’s light in the room and you suck this energy away from things. People seize up when they see that sort of stuff. Whereas the 16mm is not small, but you don’t really know what I’m filming. It’s quite compact and people get used to not knowing what you’re doing.

Anonymous Club Review

Danny Cohen Gives Courtney Barnett the Space to Be Herself in This Masterpiece of a Documentary

Is there a comfort in the restraint? As you’re saying, you’ve got like eleven minutes, twelve minutes a day to shoot. Is there a comfort in knowing “I’ve got 24 hours today and I’m only going to get minutes of footage today”?

DC: (laughs) Yes, and no. Initially for the first six months, the takes were too short. They were like ten, twenty thirty-second takes. I was so worried about spending money on film, chewing through it. So I was just doing these really short takes. Even thirty seconds felt really long to me for a take. But then you looked at it like when you’re editing and you’re like “What was I thinking? What can I say in that amount of time?” And then I [realised] maybe that’s actually the vibe, that’s part of the sort of free flow stream of consciousness that it cuts and then all of a sudden, we’re somewhere else and it cuts and it kind of keeps rolling. But it was just so cutty and so all over the shop.

Over time, you become better at picking your moments and when you need to button on or not. And way more often than not, it’s the times when you expect nothing to happen. It’s all in that in between moments. She could be playing a massive show in London and everyone’s like “This is it, you got to be there, 5,000 people.” Why wouldn’t that be a big moment? And then you go and you film the gig and of course it’s a great gig and she’s in a great zone, she’s had an awesome gig in front of so many people. But then so has every other musician that plays this venue.

The documentary I was trying to make wasn’t about those accolades or something like that. After the first few tours, I was like “I gotta stop shooting shows” the way I was. I was shooting so many shows. And I was like, “This is great. I’ve got really good footage of Courtney playing, but just not enough of a story.” It was a good lesson.

If we can talk through the editing process as well with Ben [Hall] and the decisions for what to include, and what songs to include. Was that a discussion between you and Ben or was it a discussion between you and Courtney?

DC: Just Ben and I for the edit. I’ll answer the songs first. Firstly at the beginning of the film, I wanted to keep the songs from the record that she was touring, because the whole record was so reflective of her mood at the time where she was in quite a dark spot. And the songs were angry and the songs were about mental health and all that sort of stuff. That’s exactly how Courtney was trying to work through those things, by putting it into that album. And I wanted the songs to reflect the mood of the album and the mood of how she was on that tour. Songs like ‘I’m Not Your Mother, I’m Not Your Bitch’, any of those heavier angrier moments.

And then even when she sings Sunday Roast at the radio station somewhere in Europe. There’s something about that song that was kind of reflective of her mood on tour, that she has to keep on going, and she’s just praying for a day off. So I was always trying to find songs that would match the mood or match where she’d come from. And then that just shifted naturally to when she started writing the next record that those songs are a lot lighter, because she was in a lighter place. And so it felt right to show those sorts of moments.

And then with the editing, we went through and catalogued everything so wrote out a script to the dictaphone. With all the dictaphone, we wrote down what themes it’s touching, and what story points it would be hitting, then the same with the footage. We’d go through and [work out] what’s happening in this shot? Where could it link to? Where’s appropriate? Where was it in actually in time? Could we line that up with the dictaphone? We had it on scene cards and printed out photos from every scene, and we just filled the walls basically with the film.

And then you just start building it in terms of how can you see that arc and that thread for people to obviously go on the journey with her but for there to be light and shade or start off maybe at the midpoint and you kind of dip down, dip down to come back up to have that contrast. But it was just so difficult to construct a story without a script or without… you’re like “I just wish Courtney would say this.” And that would get us through to the next thing. And so we would go back to the dictaphone, scrub through and try and find that moment that we’re looking for. We went mad. In a good way, in a good way. Well, it’s my favourite things to do. But yeah, it’s very difficult.

I can imagine. Was there ever a time that you were like, “Oh gosh, I wish I could just call up Courtney and go ‘Hey, this is this is what we’re dealing with in this moment. Can you give us a little bit?'”

DC: Yeah, definitely. I think the thought crossed our mind a lot. But then we knew it wouldn’t be the same tone, wouldn’t come from the same place. Those entries are so special because they’re a moment in time where she was feeling X Y, Z. You just hear it in her voice, in the surrounds. So I thought it wouldn’t work. And you’ve got to try and be as truthful as possible.

I’m curious about the decision to choose Anonymous Club as the title.

DC: It was something about that line that she says early on in the film – if a lot of people feel alone, then maybe they’re not so alone. That really resonated with me. Obviously she’s just one of many people out there. But what she’s experiencing, I think a lot of other people are experiencing the same thing. You do feel somewhat alone in that, but you’re not. And so it was something that worked really well.

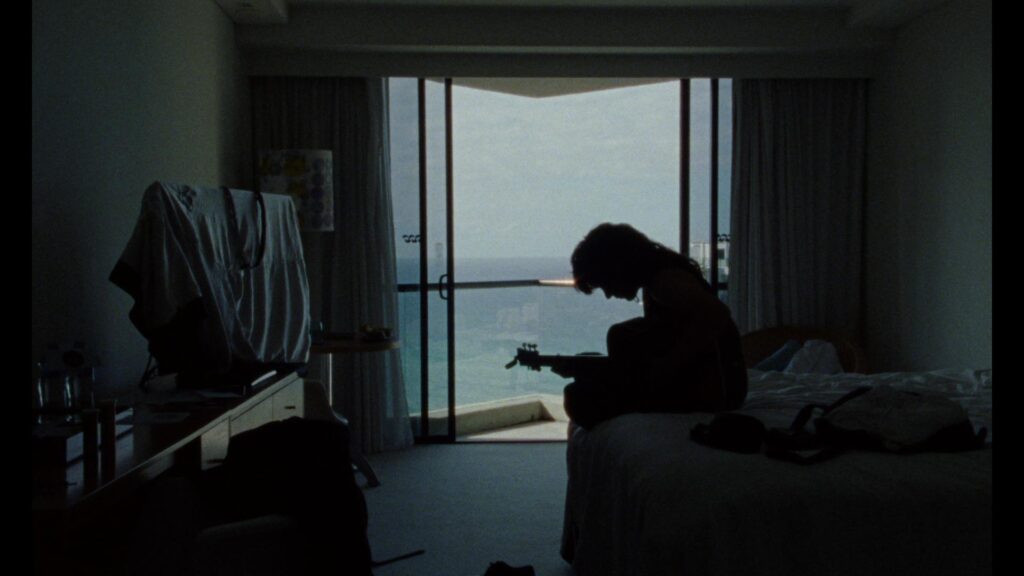

I’ve always loved one) the song; and two) the words together are quite powerful. So I feel like there’s a lot of people alone in that club. They are anonymous, but maybe by being all together, they’re not actually alone. It was something that I liked. And I remember Glendyn early on when we were talking about the story, he was like “She feels like a ghost.” Because you see her in this town, you see her there, and she’s quite quiet in a hotel room, and then she’s there, and she’s just kind of popping up everywhere. Not haunting a bad way, but just kind of like passing through time, or time and place. So I think that fed in a little bit to Anonymous Club.

It’s a great song. A very personal question is do you have a favorite Courtney Barnett track?

DC: Good question. I think it’d be up there with ‘Small Poppies’, probably because Courtney’s live performance of it really shows her chops on the guitar. There’s one particular one I love from the Lotta Sea Lice record. ‘Blue Cheese’. Because it’s just such a fun combination of Courtney and Kurt [Vile] and I had a real emotional connection to it. I was shooting some stuff for them at the time in the studio, and just seeing the vibe of that being created and then hearing it was a really special moment there. And it’s got a good level of humour.

Their work together is so nice. There’s a lightness there, it’s beautiful. For you as a filmmaker and doing music, videos and all this kind of stuff. What do you want from your career as a filmmaker? Do you want to continue doing those music videos? Do you want to continue doing documentaries or moving to feature films?

DC: Features are definitely the way to go or where I want to go. There’s a few kicking around at the moment, just things bubbling away. And same with some longer form music docs. But definitely your wacky psychedelic features in the brain at the moment. So yeah, we’ll see. I heard from a friend that it’s really good to have a bunch of films on your plate. And when there’s a roadblock for some reason, either creatively or funding or whatnot, you shift to something else. And so I’m just trying to load up.

Music videos I don’t really want to do them so much anymore. The budgets are just really, really low, which is no fault of anyone’s, but it makes it really difficult. And there are only so many favours you can call in before people are like–

“Danny, you’ve done it.”

DC: “We’ve done enough, and I can’t keep working for free.” It’s hard to wrangle people. But the [music videos] have served a purpose, I think, of learning and gaining experience and getting to work with artists before doing longer form.

I have to ask you — leaning into one of the more prominent things that you’ve been part of — the Jimmy Barnes and Kirin [J Callinan] video. What’s it like for you mentally to see that become a meme?

DC: I mean, it’s awesome. Kirin and I always talk about it. It’s just like so special that people are still reacting to it and still enjoying it and people that have no idea who Jimmy is. Every ten minutes, there’s a new comment. It’s kind of awesome that all over the world, these people are just having a giggle over something and not taking it too seriously. Really, that’s what it’s about, connecting with a large audience and people finding something in it. Even if that’s just humour. I think that’s awesome. So yeah, definitely not what anyone expected. I remember it was like sitting at 50,000 views or something. And we thought that was it.

And now look at it. It’s everywhere. Do you have a favourite of the memes or gifs or whatever that’s been out there?

DC: I think my favourite one is there was a Happy Gilmore one because he has everyone in the clouds. And I was like well, that was our VFX reference, putting Jimmy in there. When I was speaking to this guy Patrick who did the VFX, I’m like this sort of softness to it and opaqueness or whatever. That’s the one. It kind of weirdly came full circle to be taken off in that context.

That’s pretty cool. [Anonymous Club] is a really powerful film. And I know that when people head along to go and see it, they’re just gonna love it even more and discover Courtney’s music in a way that really deserves to happen. I think it’s a very fortuitous time, because I know that she’s heading out on tour as well. The film is getting released at the same time as she’s going out on tour. Is that correct?

DC: Yeah. I think the tour starts next week.

This morning. I rediscovered the concert in Piedmont Park a couple of years ago, three or four years ago, and so I was listening to that again this morning. I just loved her variety of – how the actual place that she’s playing reflects – creates a vibe of how she’s actually going to be playing the songs. It’s great to see.

DC: We had great footage of that show. Just too much.

What are you gonna do with that? I imagine you’ve got like troves of it all. Are you gonna — in ten years from now–

DC: I don’t know. I think I’ll definitely delete all the dictaphone. I don’t think that needs to be stored. I guess it’s more in Courtney’s world than filmmaker world. But there are so many shows. It’s a great document of all that stuff.