Help keep The Curb independent by joining our Patreon.

I broke into a wide smile at the opening title of Antlers, being a quote recited in what I assumed was a First Nations American language that immediately placed this in my new favourite subgenre: eco horror.

Certainly director Scott Cooper has confirmed in a super spoilery interview that the creature at the centre of this story represents the desecration of natural resources. The setting, an Oregon mining town, is shown as a bleak ugly eyesore despite incredibly gorgeous mountain surrounds. And in Keri Russell’s very first scene, her character Julia talks about how First Nations myths and legends function as cautionary tales which of course include the relationship between humans and the natural world.

But as it turns out, the eco horror aspect of Antlers is subsumed by a fairly powerful narrative of surviving child abuse, driven by the mirroring performances of Keri Russell as Julia and Jeremy Thomas as Lucas, a withdrawn painfully thin student in her class. Abusive dads cast monstrous shadows here, and there’s an impressively nuanced and no less terrifying depiction of the psychology of abuse victims trying to rationalise and negotiate what they need to do to survive.

I was reminded of so many Stephen King novels where the protagonist is a child or adult grappling with an abusive father or the memories of such, and sometimes like in The Shining (the book, never the movie) also struggling with the terror of replicating that abuse as a parent. Antlers isn’t King property, it’s based on a short story by Nick Antosca, but certainly fits in the oeuvre of horror as allegory for so very many things. For a while there, I was seeing the clear analogy for how a parent’s addiction can wreck the daily life of a child. It’s almost an embarrassment of riches, so many ideas in this one narrative and not entirely fusing together. By the time we get to the third act, all the other subtexts fall away, and the one analogy becomes pretty overt.

As you would expect, Keri Russell’s intensity perfectly suits such a moody film and the genre itself. Six seasons of watching her kick arse on The Americans means there’s absolutely no doubt that she will eventually annihilate this monster, metaphorically and literally, and that it’ll be glorious. Which makes it all the more unnerving to see Keri scared. “But Keri’s never scared! Oh wait. Right, right.”

The few scenes she has with Jesse Plemons as her brother Paul are enough to make you wish someone would cast them in some two-hander chamber piece where they could unleash so much emotional rawness on each other. For his part, Plemons has a moment where he gets to display the exquisite emotional silence he does so well.

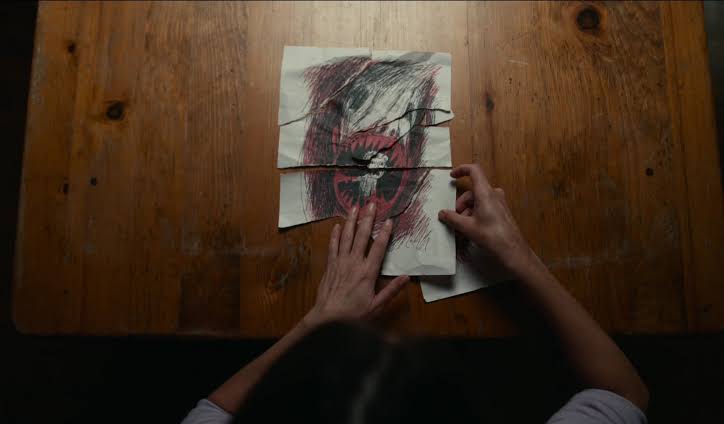

Jeremy Thomas’ performance as Lucas is really the centre of the film, a frail little figure with huge wary eyes and extraordinary lashes, huddled in so much traumatised stillness. There’s only a little nuance to Lucas, a flash of sharp intelligence early in the film and then that absolutely unnerving moment of victim rationalisation.

The cinematography by Florian Hoffmeister makes for some truly heartrending images framing a desperately alone kid trying to survive a traumatic situation. There’s a wonderful use of red flares and flashing police lights at the start and the end but for the most part, all the interiors are very dark, probably too dark for some, with a lone beam or circle of light picking out the glint of metal or a figure. The colour palette is moody af; even the vibrance of autumn is dulled to a bleak drift of leaves and sky. But happily, the showdown is drenched in eerie red, and the gory bits are wonderfully bloody and very detailed.

I wasn’t affected by any of the jump scares – which is fine, that is not a criterion by which I judge horror – but apparently one moment in particular scares the hell out of people. I did find the score by Javier Navarrete remarkably melodic for the genre, especially these days, and still thrumming enough to be ominous.

Halfway through the film, I realised abruptly that Julia is the only female role of significance in a cast of so many men. There’s one mother in one scene, and a female principal who gets quickly shuffled off, but no other women with actual lines. The coroner could have been female, the sheriff’s officer could have been female. Hell, so could one of the important kids.

And then that weird regression extends to the First Nations representation. For a film that begins with an Indigenous voiceover and draws on Indigenous myth for its creature horror, there is exactly one Indigenous character in that white cast, and he has exactly three scenes, one of which totally turns him into the trope of shaman imparting knowledge to the white protagonists.

That took me sharply back to the problems I had with the last Scott Cooper film I watched, Hostiles (2017), where the First Nations characters were merely instruments to facilitate the white characters’ emotional arcs. Both films speak so much of white guilt — in Hostiles, it manifests obviously in the theft of Indigenous land from Indigenous people, and their mistreatment. Here, it’s subtler in a phrase like “when you take what’s not yours”, in the desecration of the land by mining operations, and in the warning about angry ancestral spirits from the First Nations character to the white protagonists. It’s not hard to imagine how different this film would be if one of our protagonists was an actual Indigenous person, and how that would complicate the final battle with the mythic creature.

Having said all that, Antlers is a wonderful title for this story, evoking the lethal strength of nature directed in self-defence or outright aggression against human encroachers. Though never seen here, the stag is such an iconic American image, essentially male and patriarchal, standing bold against the big sky. For all its flaws, Antlers is a pretty interesting exploration of the dark shadow cast by that unseen shape.

Director: Scott Cooper

Cast: Keri Russell, Jeremy T. Thomas, Jesse Plemons

Writers: C. Henry Chaisson, Nick Antosca, Scott Cooper, (based on The Quiet Boy by Nick Antosca)

Cinematography: Florian Hoffmeister

Editor: Dylan Tichenor

Score: Javier Navarrete