Help keep The Curb independent by joining our Patreon.

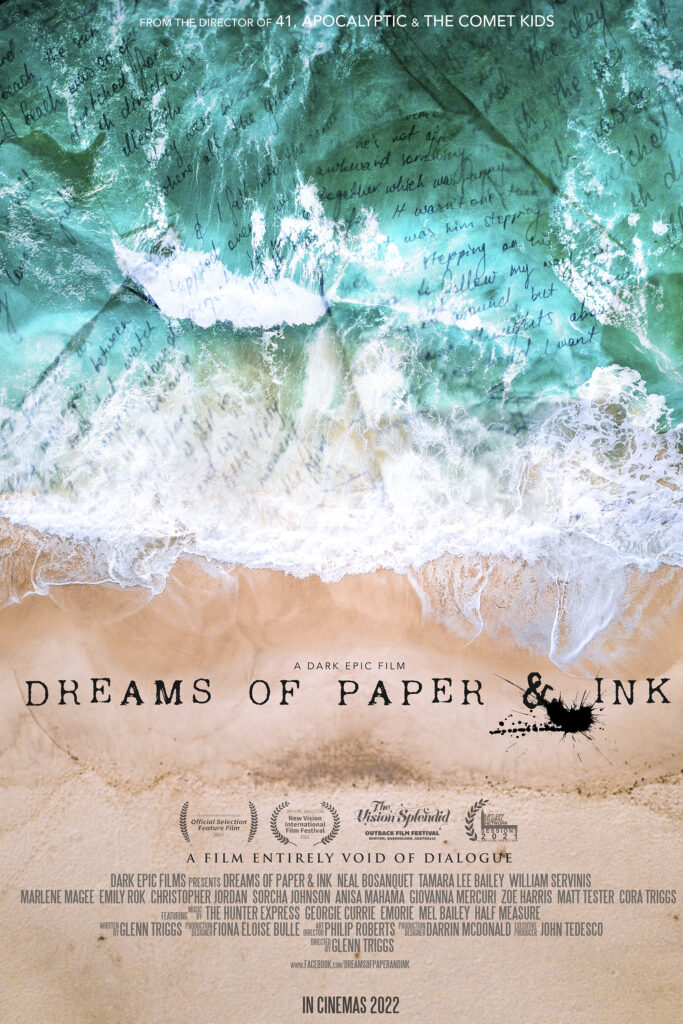

Glenn Triggs is an Australian filmmaker who could easily be considered the poster child of the indie Aussie filmmaking scene. With a slew of feature films under his belt, from 2012’s time traveling flick 41, to the found footage horror film Apocalyptic (2013), to his 2017 family friendly eighties homage The Comet Kids, Triggs is a filmmaker who manages to slide between genres comfortably with a limited budget.

Now, in 2022, Glenn moves into his most mature film yet: Dreams of Paper & Ink. In this mostly wordless film, an elderly novelist, Wade (Neal Bosanquet) is asked to deliver a book that is a little more personal than his previous works. Turning to his past, Wade recalls his first love, Kina (Tamara Lee Bailey), and the foibles of his younger self (portrayed by William Servinis). With wistful music and a nostalgic lens, Dreams of Paper & Ink leans into a feeling many of us have as we grow older and reflect on the ‘what if’ of our past.

In this interview, Glenn talks about what it means to be an independent filmmaker, the audience he writes for, and his relationship with the art of filmmaking.

Dreams of Paper & Ink launches in select cinemas in May 2022. Visit the Facebook page for screening details.

Congratulations on your film. I’ve quite enjoyed your work before. This is a bit of a different kind of film compared to what you’ve previously done, which is horror, family-friendly films. This is more of an adult fare. Where did the idea and the notion for doing something completely different come from?

Glenn Triggs: I always like to make a different film each time I make a film. I don’t like to keep doing the same thing over and over. The scripts I’m working on at the moment are completely different from anything I’ve done before. It’s just fun to try something different, I guess.

With this film, it sort of came to me. I didn’t really seek this movie. I had these sorts of emotions in my head for many years; I listen to music, and I love making films. And then for some reason, my brain decided to put all that together. And the next thing I know, I’m thinking about sequences while listening to music while driving the car. And I’m like, “Ah, that would make a cool scene. Maybe I can put that into a film.” And then that happened about ten or twenty times with different songs. And I’m like, “I could probably make a movie somehow out of all these different thoughts.” It just very organically came to me.

I wanted to try something a bit more artsy, I guess, something a bit more adult, like you said, and more serious. It was over like six months, little bits and pieces appeared here and there in my head mostly.

When you get an idea for a film, what is your process of getting it from that idea into a script into creation? Can you walk me through that?

GT: I just love it so much. I try to make movies mostly for myself, I don’t necessarily aim for a particular audience. I had a love of movies when I was a kid. And the love of movies that I had as a kid, I don’t necessarily have any more for new films, which I kind of find a bit sad. But from the ages of five to eighteen, I absorbed every movie I could fall in love with back at that time, and I’ve carried that with me. So now I love making films a lot more than I like watching films. I rarely watch movies these days, which is sounds kind of weird to say.

I love the process so much. It feels like fun to me, it doesn’t feel like work. It just feels very natural and a fun thing to do. I do a lot of other video work on the side to pay for these films, because the films don’t necessarily make too much money, unfortunately. So the process of making a film, I try to inspire myself. Usually it’s with emotions and music. I’ll think of a particular scene or sequence, and that is usually the reason why I want to make a film. I know with The Comet Kids, the scene at the end when they were running towards the dog – that was the main reason I wanted to make that film. I tried to work out a story around that scene, which sounds weird to say.

With Dreams of Paper & Ink, it was the end sequence on the beach, because I had a dream about that. I was on this beach and I saw a girl, I’m not sure whether it was meant to be like a manifestation of like an ex-partner or something; but I had this loving-loss feeling on this beach in this dream. And when I woke up, I’m like “I need to somehow put that on screen.” That was also part of the process. So yeah, I get very inspired.

And then I find writing actually quite difficult. I do struggle with writing. I procrastinate really badly. And so when I write, I try to say to myself, “Just write a page a day. If I can just do one page a day, then that’s great.” Sometimes I’ll do forty pages in a day. Sometimes I’ll do none for a month. So I always aim for one a day, but I never necessarily hit that target. And I never really finish the script. It gets to a pretty good place. But I know that when I’m casting or when I’m filming or when I’m editing, I can make changes then. It’s a very scarce blueprint for me. I never really put everything into it. And if you read the scripts and then see the films that I make, there are a lot of differences and you’ll be like, “Okay, so you’ve obviously come up with that idea later.”

Shooting is always stressful. Especially the lead up to the shooting, the preparation stuff is always a stressful process, trying to get all the contracts drawn up and all permission slips and all location fees and all the paperwork stuff. I remember when we were doing The Comet Kids, I spent about two months trying to prep that film mostly by myself. And I remember being at my desk one day, and I think I was just like punching my desk or something because I was so frustrated with trying to get it all to work. And my wife’s like, “Are you okay?” “Yeah, just stressed.” But then it all worked out.

Editing is where I have the most fun. Editing is definitely my thing. I love editing, I edit all the time. Every day I’m editing something, whether it’s a family video or a movie or a trailer or whatever I’m doing. I just have to edit something. Which is heaps of fun.

I guess the post process is trying to get the film out there, and that also has its own difficulties, trying to get people interested in these super low budget movies that sometimes get into the mainstream and sometimes don’t. But I love all of it. I get obsessed with all of it. And even when I’m over it and I hate it, a few months later, I’m back into it again. I don’t know where it comes from, it’s just in me somehow. It’s an itch I just love scratching.

Exactly. It’s that creative drive, there is something about that whole process. I’ve not made a film myself but I know what the creative push is like. And it’s a really unique process that you can’t really get anywhere else.

GT: No, I think if you really sat down and thought about all the stress and all the hours you’d have to put into a film, you probably wouldn’t do it. I know I wouldn’t. If someone said, “This is all the days of work you have to do to get a film made,” I’d be like, “I’m not doing that.” But when you’re in it, it is a drive that – you don’t necessarily want it but you love it sort of thing. It’s weird like that.

For the last year, I’ve had no interest to make another film. And then in the last two weeks, I’m like “I need to make another film soon.” I think because Dreams of Paper & Ink is sort of coming to an end as the screenings will start up soon. There must be something in my head that’s like, “All right, it’s time for the next one.”

COVID slowed down this production like crazy. This movie should have been out about a year and a half ago, but it just didn’t happen. It’s all happening now. And I do love this film, but I always find every time I screen a film, as soon as it’s finished, I get severely depressed for about twenty-four hours. It’s happened every single time, every movie I’ve made, because I know that the process is actually over now. I don’t have to worry about emailing, cinemas and contacting producers and all the different bits and pieces that go with it, it’s actually finished. So yeah, I always get really depressed and I really hate that because I can’t enjoy going to sessions and watching it with people anymore. It’s kind of like no, that’s it now, it’s done. So that’s kind of weird. It is the journey, not the destination, for sure, which is strange.

For something like The Comet Kids which gets screened on TV quite a bit, does that give you a bit of a buzz knowing that somewhere out there in Australia, somebody’s going to be watching it?

GT: Yes and no. I do love that it’s been on TV and it’s been in all these different countries and stuff. If someone had said to me when I was younger, “Your movie’s going to be on TV when you’re older,” I’d be like, “All right, that’s it. I’m going to stay up all night. I’m going to watch the film. I’m going to get all my friends over.”

The reality is okay, it’s on TV, all right, I watch five minutes and I’ll turn it off. It’s weird. It’s really weird because it’s not what you expect it to be, the process. I really thought it would be the opposite, I’d be so excited, jumping around the room. I remember when Apocalyptic first went on TV, it was on at midnight. I think I stayed up till midnight, I watched five minutes and I just fell asleep. I was like, “I’ve seen this a thousand times, I don’t need to watch it again.” The after buzz is not really there, which is really bizarre.

I remember Peter Jackson saying he’s only ever watched his Lord of the Rings films maybe once since he finished them. And he doesn’t think too much of it, he’s just like, “That was complicated and stressful. I’ll just move on to the next thing.” I think that’s what a lot of filmmakers do. You just want that next buzz, you don’t really care too much about the after buzz of the last project. Which is weird. Doesn’t make any sense.

Oh, no. I interviewed Bruce Beresford last year, and at the end of the interview, I was talking about the fortieth anniversary of Puberty Blues and the fortieth anniversary of Breaker Morant. And I said to him, “Do you revisit your films at all?” And he’s like, “Do you reread any of your interviews or reviews that you write?” And I’m like, “Not all the time.” And he’s like, “Well, it’s exactly the same for films. I don’t do that.” I think about that quite a bit, because it seems so bizarre to me.

GT: It doesn’t make any sense. I have no idea why that is. Like I want to enjoy it, I want to, like I said, jump around in the lounge when it’s on TV and invite my friends over and be excited for it.

I love when someone reviews films. It’s always great reading reviews. I get a buzz out of that, because it’s someone explaining what they liked about it. But just having a movie out there in the world is unfortunately not as exciting as I wished it to be. It’s far more exciting creating the film and wondering what will happen to it. That initial spark of the creation is far more fun than having the film finished, which is annoying. I’m annoyed by that, I want to enjoy it, but I just can’t.

Let’s talk about the visual style of this film, because there are visual moments here which are just really exciting. It’s those frozen moments where you’ve got the character standing there and then being frozen in time while another character is walking through that same moment. It’s visually impressive. Are those kinds of visual moments in the script, or is it the script first and then you come up with the visual moment for what’s on screen?

GT: I usually have an idea of what it will be like as I’m writing the script. For that particular scene [at the end of the movie], I knew I wanted it to be a sunset, to look very nice and stuff. But you don’t really know till you get there on the day. I don’t think I storyboarded for this film at all. I just knew that I would turn up and look at the room or the location and just figure out what we’re going to shoot in the space. Because everything changes once you’re there and you can prep as much as – I had a few ideas for particular shots.

There’s a shot in the film where younger Wade is typing, and the camera starts on his face and it goes down to his hands, but it’s older Wade, and then the camera pulls back and you don’t realise that he’s aged. I didn’t want that to be a cut. I wanted that to be an actual, you know, full take. So Will [Servinis] had his head over Neal [Bosanquet]’s shoulder, and Neal had his head really far back. You just saw Will’s face and then as soon as the camera went down, he jumped out of the way and Neal went in and took over that. That was sort of planned, but visually, it all happens as it happens, and you sort of get lucky.

I know with Apocalyptic, we got very lucky with the fog. We had like a really foggy morning and I remember thinking, “Oh, we can’t shoot this, like it’s too foggy. It’s not going to match up with what we’ve shot.” And everyone’s like, “But it looks amazing. You should run out there and shoot.” I was like, “Oh yeah, you’re right. I should just take advantage of this. Because this this actually looks crazy.” And a lot of people have always commented on that. They’re like, “The fog and the grass and the house looks great.” So you just take what you get.

We got very lucky with sunsets when we shot this film. The day we turned up, we got there at 4pm and the sun was just perfect. We started shooting and I was really nervous about that scene because for me, it was the pivotal moment of the whole movie, it had to be this perfect sequence. Yeah, we got lucky. Then we went back and shot again because I think one of the drone shots I did, I had the slow-motion settings wrong, so I knew I had to go back and reshoot it. And we got a similar sunset again. That was the only two days of the whole shoot we got good sunsets and we just happened to be at the beach at that time, shooting the scene. All the other days were cloudy and all that sort of stuff. So we just get lucky. Sometimes not always. But on this film, yeah, we definitely got lucky.

I let the scene sort of – not speak to me necessarily, but I look around and just look at the light, “Okay, the sun’s coming from there, it might look really nice, you sit over there, okay, you sit over here. Okay, it looks good. If you’re over there. I’ll shoot this way. No, that doesn’t look good. I’ll shoot over this way.” I shoot a few different ways, and then eventually look in the edit and be like, “Okay, well, that second shot worked the best, I’ll use that one.” So it’s trial and error. It’s not like I know exactly what I’m going to get, I’ve pre planned it. It’s I’ll shoot a few different ways and see what looks the best, I guess.

One of the key things about this particular film is there’s pretty much no dialogue here. So we are getting to know the characters through their actions, through who they are as people, and just sitting there and watching them. One of the things which I found really interesting was that there are moments where we learn about who the character is through small things like dropping food into the bathtub or dropping pizza on the ground. How do you go about finding those kinds of moments?

GT: I based a lot of that around myself. A lot of me was in this film. So it actually made things very easy, especially when the actors were like, “Where should I be sitting? What should I be thinking?” I was like, “Oh, well you’re thinking this,” because I felt as if I’d been through all of this myself.

Little moments like that were in the script. Every time I had some sort of moment that would happen, I made sure it had a bookend to it. It wasn’t like a one-off moment. So he drops two things – there was going to be three things – but he dropped two things and just ate it off the floor. Because when I was younger, I was happy to eat food off the floor, it wasn’t a big deal for me, like it is now. (laughs) So yeah, I took moments out of my life basically and made sure they were always bookended to some degree. So like when he’s trying to learn how to play guitar, and he can’t play guitar, and then later he can play guitar. There’s a duality to it, it’s not a singular moment of something that goes nowhere.

A lot of this film is about reflecting on yourself, reflecting on the past and learning about your past actions. You were talking about this having elements of you in there. Is it hard to reflect on yourself in your own work?

GT: No, it’s actually very easy. I find it very easy, because I knew I wanted to get this emotion out of my system. I went through this relationship when I was a lot younger. And I think your first love always affects you the most, I always feel like with the first love, you do actually connect with someone, there’s some sort of…. like you lock onto a person. I think there’s some sort of biological thing that happens.

And as soon as it doesn’t work out – because it usually doesn’t, like I know a lot of people where it didn’t work out. That’s what I’m hoping the audience will get out of it. It’s very difficult to miss someone that’s still alive, [who] doesn’t want to speak to you anymore. And that was part of it too: like this particular girl that the movie’s about, she never wanted to speak to me again. I sort of thought that’s a good way to [do] the movie, there’s no dialogue because we’re not talking. That was an interesting angle to go from as well.

I went by feelings for this movie, whatever felt right, I just did for the film. I knew I wanted to show the relationship as realistically as I could, and then show it fallen apart and then what happens afterwards and how you cope with things like that. It was actually quite cathartic. It did get it out of my system, which is great. It felt like it’s out of me now and it’s where it should be, which is on digital or film. It’s somewhere else, which is great.

Has your partner watched the film and what were her comments on it?

GT: Yeah. Well, her character is essentially in the film. She’s the wife at the end and throughout. I won’t go into too many details without ruining too much. But the actions that she’s doing in the film show all the things that the wife was there to help with, and especially at the end when she’s in the bed, but I won’t go into that detail. But what she’s doing in the bed is important. Once again, it’s meant to have a [bookending] factor to the other girl that didn’t want to necessarily do what she was doing.

My wife actually really loved it. She’s watched it, I think, four or five times. And every time she’s like, “I think it’s your best film.” I think she got something out of this one, which was good. And she’s probably got a very similar sort of situation to me, she had a relationship when she was younger, you lock on to someone, it breaks up, and it affects you to some degree, but you learn from that. That’s what the whole movie was about, how you learn from mistakes, how you learn from things that you do in the past, and how you can better yourself from that. That’s all in the film. Like the swimming scene especially, when she’s in the water and she wants to swim, but he doesn’t want to swim. And then, you know, he learns from that.

It’s the realisation of maturity, which sounds almost like a trivial thing, because it’s what happens to us all as we grow older and we theoretically should mature. But that reflection doesn’t often happen. It’s such an internal thing, at the very least. And it’s really quite powerful to see it recognised and realised in a way that is very relatable, that we can all sit there and go “All right, this is not my exact story, but I relate to what’s on screen.” And that’s something quite great. So congratulations, you’ve done a good job there.

GT: Thank you. I think a lot of people have definitely related to it. And like you said, it is internalised. A lot of people don’t talk about this sort of stuff. It’s interesting to make a whole movie about that.

As we lead into wrapping up, I’m fascinated about what it means to be an Aussie filmmaker for you. What does the Australian identity mean to you as a filmmaker?

GT: That’s a good question. I’ve have in the past embraced the Australian film industry, and then I’ve also gone completely away from it and tried to be as far detached from it as I could. When we did The Comet Kids, it came down to a point in the two weeks before production whether it was going to be an American-spoken film, or an Australian-accented movie in English. I tossed and turned – it’s going to be much better if it’s Australian because all the characters can just be themselves. No one has to fake an accent.

But then I thought it’s not going to do well if it’s Australian. I just knew it wouldn’t. And so made the decision, made it American, was happy with that at the time. And the movie went out and it did great because American audiences saw it. It got released on DVD over there, and it was in cinemas all over the place. It did really well in the market. And then I sort of regretted that because I’m like I wish I had kept it Australian because it would have been a bit more sort of – what’s the word? I can’t quite think of the word, but just it’s just more – all the actors would have been more themselves. Everyone had to act and then also put on another act on top to make it that American way.

And then when I did Dreams of Paper & Ink, I was like “I don’t want to do American accents.” Because I think Australian actors can sometimes struggle with it. And then I didn’t want to do Australian accents, because I didn’t think it was going to do well in the marketplace. So when I did think of having no dialogue, I was like “This is perfect. It’ll work anywhere, hopefully.”

But yeah, it’s a weird one. For whatever reason, I’ve never really been into Australian films. There are some that I love and watch, but there’s only a very small handful. Unfortunately, I’m brought up on so much American stuff. That seems to be where all my time goes if I’m watching films. My next film potentially might be a Scottish film, going somewhere completely different.

But as far as Australian film goes, it’s always been a tough one to make Australian films that do well. Even for people that do successful films, they do so well in a small pocket of the world, but it’s rare for an Australian film to get through and do great things on a larger scale. Not that I necessarily want to do larger scale films, but I think it just plays easier in the marketplace, unfortunately.

I think Australian films just don’t take big enough risks in the marketplace because we’ve only got one or two funding bodies at the moment or something like that in Australia. There are only so many avenues, other than all the American productions that are coming over here to shoot stuff. For someone like myself to try to get Australian funding to do a film, it wouldn’t necessarily be the film I’d want to make.

Because there’s Screen Australia, and then each state has their own funding body. They all have their own agenda of what they want on screen. What Screenwest wants is different than Film Victoria.

GT: I’ve been in touch with them in the past, I’ve never had any luck getting through. I’ve written many scripts and just never had any luck. So I sort of gave up on that whole thing and thought I’m going to go do my own thing and do the best I can. That was sort of my goal.

I think it’s really inspirational. And I know that that word is kind of twee and frustrating, but it is inspirational to see you out there and just going, “All right, you know what, I’m just going to make these films and do it myself.” Because I think for a lot of filmmakers, especially emerging filmmakers, they look at what’s going on, and they go, “Ah shit, I’ve got to go through all these hoops to get funding and get it made.” And then there’s somebody like you who has not just one, not just two, but like five, six films under their belt and actually have them out the world and have audiences who have seen them around the world. It’s good to be able to point to that and go, “Well, look at what Glenn’s done, look at how he’s been able to do that.” We need more people like you out there who are creating films like this, we need a generation of filmmakers who don’t have to ask for that approval.

GT: That’s the hardest thing. If I had gone through the proper avenues to make films, I probably wouldn’t have made any films yet. I know that I’d still be struggling on my first movie, trying to get funding for it or something. It’s a nightmare, going through the hoops that they put out there.

And you can make your own film, especially [with] all the technology that we’ve got now, all the computers and the editing power we have and the little cameras. I shot this movie on a $2,500 camera, just a little cheap Sony A7 camera, A7 III. All the stuff is there. Things like YouTube: everyone’s teaching each other and learning things. I learned from YouTube how to use my new camera when I bought it for this movie. I watched tutorials for two months trying to figure out the best picture profiles and best settings and indie filters to try to make it look right. Everything’s out there and I think a lot of people are jumping on that. But yeah, a lot of people do think that to make a feature film and get it out in the world, like you said, is so out of their reach. I don’t think it is at all. We just go out and do it, which is good fun.

And then you approach cinemas, fingers crossed, some of them will play it.

GT: With 41, the time travel movie I shot years ago, that’s done great online. I’ve had such a massive response of people online. People email me all the time, it’s like their favourite movie. That’s nuts.

What does that do to your mind when you get people saying that to you?

GT: I don’t really believe it. I’m like, “Nah, there’s other movies that are way better.” But people just love the story of that film. They can’t believe that someone made a $5,000 movie that just, you know, blew their minds and was really emotional and all that sort of stuff. But deep down, I don’t actually believe it, I’m like they just may be saying that to be nice. But yeah, 41‘s been the biggest reaction online.

When we entered that into festivals, it won every festival we entered, which was nuts. I’ve never had another movie do that since. I think we entered The Comet Kids into about twenty festivals and got into none because everyone had seen that movie before, everyone knew that film. But 41 was something different that had that indie angle, I guess, and did very well at festivals for some reason. And Dreams of Paper & Ink didn’t do well at festivals. So I don’t know what the magic formula is.

There’s a lot more movies out these days. Every festival is getting something like 5000 movies sent to them, which is insane. It’s hard to get seen unless you’ve got famous people involved, and that gives you a huge leg up. But there could be many other movies that are far superior that have all unknowns in them. And I prefer movies with unknown actors, I find it more of a unique experience. You know, not another movie with Tom Cruise, but a movie with people you don’t know and you go on their journey because it feels unique.

I think certainly for a lot of indie films from what I’ve seen too is that real need to be as original as possible. And that’s got to be hard. It’s got to be hard to have that two-sentence logline that captures somebody straight away and goes “All right, cool. I know exactly the kind of bizarre thing.” Like Everything Everywhere All at Once is a simple ‘Michelle Yeoh multiverse’. That’s it. And that’s a bizarre concept. We don’t get to see that very often. But that’s the thing about indie films is that they’ve got to push through those 2,500 films that are getting submitted to festivals all the time.

GT: I remember Kevin Costner was once quoted as saying that a good idea will put a smile on your face. And I’ve always loved that, because if I get an idea – and I get ideas all the time for different things, whether it’s just a scene or a whole movie or something – I love trying to figure out ideas in between other ideas, like what everyone else already thought of, and what someone never thought of before. It’s really difficult, but I’m always on the lookout.

I love the idea of film can be anything. I think there’s so many stories that have never even been told at all yet, and different ways of telling stories that no one’s even thought of. We’re very much stuck in this three act, two hours construct at the moment. There’s obviously different platforms and formats that show all sorts of different videos in different lengths. We know like podcasts have become the new thing at the moment. And then like TikTok with fifteen second videos which has been a whole new thing as well, and its own medium.

I think there’s a different way to tell movies, and I’m not sure – we’re still experimenting with what can be done, I guess. I love trying to figure out yeah, what else can you do with the film. I’ve got a bunch of ideas which I’m working on at the moment. I haven’t really finished any of them, but I’m working on them. And I’m trying to come up with something that’s different, unique, and original. I do like original ideas.

That’s where Dreams of Paper & Ink feels original for me, because it’s probably my first truly original film. I think all my other movies have been very much copy a bit from this movie, copy a bit from that movie, and sort of put my own spin on it, but this one was completely myself. So I’m really proud of it in that sense, which is good.