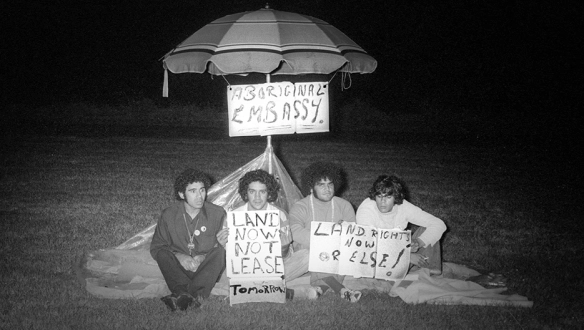

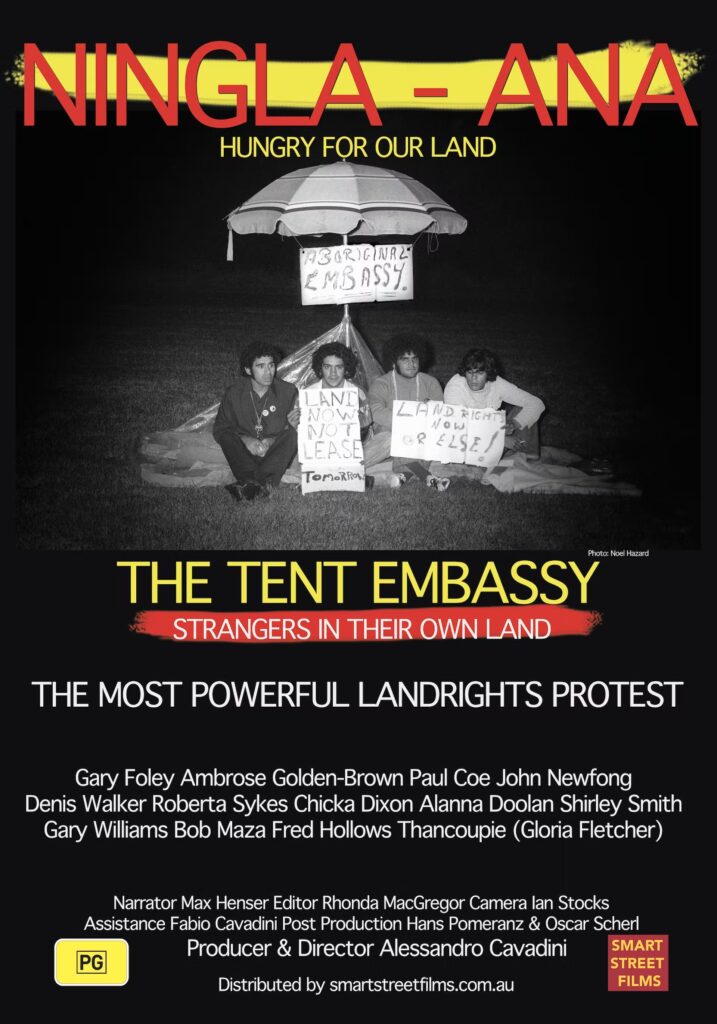

2022 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the landmark protest documentary Ningla-A’Na, Italian-born Alessandro Cavadini’s film about the early days of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra and the fight and struggle for land rights in Australia. This is a powerful and vital historical document that almost found itself lost to time, and this week it returns to cinemas for audiences to engage with a part of Australian history that deserves remembering.

Ningla-A’Na – “hungry for our land” – features footage of important political organisers and figures within the Black Liberation movement like Gary Foley, Paul Coe, Roberta Sykes, Isabelle Coe, Bob Maza and Shirley Smith, amongst many other Aboriginal figures from the 1970s. Initially detailing the protests and fight for rights in front of Parliament House, Ningla-A’Na additionally documents the Aboriginal Medical Service, the Aboriginal Legal Service, and with a stirring performance late in the film, the National Black Theatre.

Ningla-A’Na shows the smothering impact white voices have when it comes to overwhelming and silencing those of Aboriginal activists. Early in the film, Gary Foley argues with a white woman who tells the group of Aboriginal protestors how she feels they should behave. There’s a lot of ‘should’s being thrown around – “You should listen.” “You should be grateful.” “You should not be so angry.” – I’m paraphrasing, but these ‘should’s are the same ‘should’s we’ve heard in recent years in response to Black Lives Matter protests and deaths in custody.

Later, a group of white women try to push the Aboriginal women into joining the feminist movement of the day. It’s called the feminist movement, but it deserves to be labelled the ‘white feminist movement’, given how much the white perspective dominates and overwhelms the Black movement. Internationally, white feminism often ignores and fails to consider what Black feminism or Aboriginal feminism looks like, and Ningla-A’Na stands as a salient reminder of how long that fight has been going on for.

When viewed in 2022, Ningla-A’Na becomes a source of anger and frustration at the political system that exists in this land we call Australia. The continued neglect for the health and wellbeing of First Nations people, alongside the rampant destruction of their land, highlights how little has changed since the 1970s. As we move towards a national debate about establishing a Voice to Parliament – which in itself will come with a contentious referendum and the pointed racism that will no doubt eventuate in the media cycle – this documentary stands as a reminder for us white folks in the world to shut the fuck up and listen.

Ningla-A’Na is still as powerful and important as it ever has been. It’s in limited cinema release around Australia now.

In this interview filmmaker Haydn Keenan talks about the restoration process of Ningla-A’Na, creating Smart St Films alongside fellow filmmaker Esben Storm, and what excites him about storytelling.

This interview has been edited for clarity purposes.

Can you talk about the discussions that Esben and yourself had when creating Smart St Films?

Haydn Keenan: It really wasn’t a discussion, I suppose. We were setting about trying to make our first film, a little thing that Esben directed and I starred in called Doors [1969] when we were at University High School. And one of our little group suggested that we really should be incorporated, I think it was so that we could get sales tax deducted from purchases of film and processing and all that sort of stuff. There was about six of us from Uni High – I think we lied about our age – and we contacted the Corporate Affairs Commission in Melbourne and registered our little company in I think it was 68-69 while we were still at school.

You had a book in those days where you had ‘articles of association’, it was called, and it said what the purpose of the company was, and ours was ‘to make films, operate circuses, funfairs, sideshows, entertainment’. It was just this fantastic collection of eccentric Edwardian sort of entertainment that we were to do with this little company. And it sort of kicked off from there. Some of the other chaps fell by the wayside and went off to do other things in their lives and Esben and I pressed on with Smart St Films. Then he left to form Storm Productions to make In Search of Anna.

At that stage Smart St had a minor studio up in Bondi Junction in Sydney. It was incredible. It was a gothic Victorian era mansion with marble fireplaces and polished cedar floors. It was an extraordinary place. We had three or four editing rooms, a 40-seat theatrette, we had a minor amount of sound mixing. We had metal workshops, storage, production offices. It was an extraordinary Creative Hub out of which a number of films – not always ours – [were produced]. The purpose was to open up a facility that would be available to other filmmakers. And there were bands rehearsing and films being made and shot and so it was really quite an extraordinary minor version of Andy Warhol’s The Factory. There was all sorts of stuff going on in there.

That was in the late 70s. And we sort of pressed on and in the late 80s we started thinking that we had to start getting real about distribution, and started distributing. We made a film called Going Down, we’d had to distribute 27A ourselves, our award winning first feature film. We started having a little bit of understanding of the ropes of how distribution and exhibition work. We’re sort of a mini-minor media empire integrated vertically and horizontally and about three metres by four metres. We develop films, we make them, we distribute them. We sold a lot of stuff to Foxtel in the old days. We’ve got stuff on Stan., we go out through DocPlay. We sell to TV and we do the same internationally. It’s not world-shattering figures, we don’t have a big catalogue of films, but they’re all good films.

Did you ever have an idea that it would be around for so long?

HK: No, I suppose not really. But then you didn’t have any idea of longevity when you were 19 anyway. We’ve been [going for] 53 years now. We’re not the biggest by any stretch, but we’re one of the oldest. We’re still out there, still working the left field. The middle of the road is highly over supplied in Australia. We keep our audiences front and centre and work hard, even if a little eccentrically or in a guerrilla fashion to bring projects to them, and in a way that they will find hopefully, entertaining, and value for their money. We have great respect for the fact that people spend their hard earned money and want to come out having seen a $13 film having paid $12.

Now you’ve got Ningla-A’Na returning to cinemas. Can you talk about the journey to getting this film back out there? And was the intention always to have a 50th anniversary celebration?

HK: Not really. It was a little bit serendipitous, where the materials we had to work with were ageing, the prints were in very poor condition, the videotape from the prints was one inch film video which is virtually unplayable anymore. And we thought we really had to do something otherwise this film was going to slip into oblivion and be sitting on a shelf in an archive somewhere. We got the camera original, what they called the A- and B-Rolls, that we used to make the prints. And they had quite a few problems in their condition. After they were scanned, we then had to send them off to India to have them repaired frame by frame. In order to do that, we had to run a crowdfunding project to try and raise the money as we couldn’t raise any real interest from the cultural authorities in Australia. Which is really quite surprising for such an important film.

When it came back, it looked so stunning that we thought we should try and do something with it. And before we could do that, we needed to get the picture graded, [where] the black and white is all levelled up and brought to a high polish and then we had to get the soundtrack cleaned up. That, interestingly enough, was done at Spectrum Films at Fox Studios in Sydney. And 50 years ago, the post-production on the original film was done by Hans Pomeranz who ran Spectrum Films. He was married to Margaret Pomeranz, the critic, and their son, Josh now runs Spectrum Films at Fox. He very generously decided to make available some of their high-tech gear. In a poetic completion of the circle, Spectrum Films did the second lot of post-production, but 50 years and one generation later. It was lovely.

We’ve had a lot of support from people in the film industry. It’s very rewarding. We were really pleasantly surprised when we took it out to a couple of cinemas and they said, “Yeah, we will take it and put it on.” It’s not going to run for six months. It’s not going to be Star Wars. But we will have done it justice in the sense that from my point of view as a filmmaker, there is no point simply preserving these things and putting them on a shelf. The object of the exercise is to get them out for an audience to see them. I hope some people come out to see what I think is a really fantastic film.

And it’s at a critical time. It is the 50th anniversary, and as such there’s a celebratory element to the screenings, but with the Voice to Parliament and Black Lives Matter and the colonial revision of history happening all around the world, I think this film screening in public cinemas is a very timely addition to what I think is a pretty critical, contemporary debate.

What can you tell me about the director Alessandro Cavadini?

HK: He’s an old friend of mine. He came here from Milan, he was here a couple of years and made contact with a group of Aboriginal radicals, Black Panthers in fact, in Redfern, and through those connections was able to get a camera effectively inside the radical action that was the tent embassy. And later the development of the Aboriginal Medical Service and the National Black Theatre. This all happened in 1972, it was a pretty full-on year. And it was a guerrilla film. He might have picked up a couple of grand out of one of those experimental film fund things, but after it was shot. All of it was shot on short ends of film that were pinched from the ABC news department. Some of the stuff they were filming a bloody TV because they didn’t have enough money to go down to Canberra [to shoot]. It bears the scars of raw, immediate, radical creative input. It speaks so truly and with such great heart that it’s a tribute to Alessandro and the crew that worked on [it].

Alessandro made a couple of other films, some with another filmmaker named Carolyn Strachan. Protected [1975] is about the aggregation of very disparate Aboriginal nations and clans on Palm Island in Queensland. And Two Laws [1982] which is an examination of customary law and its juxtaposition with common law in Australia, made with the Borroloola community up in the Northern Territory. These three extraordinary films that are a great legacy. Unfortunately, Carolyn Strachan died a couple of weeks ago. Alessandro lives on the smell of an oily rag just north of New York.

What does that mean to you to be able to bring Australian culture that has been left dormant for so long back to life in a way like this with Smart St Films?

HK: It’s very satisfying. There’s a funny combination of hardnosed professional practicality where you’ve got to promote the thing, do the PR, make a poster, make a trailer. There’s an enormous amount of work. This is designed to be seen in a cinema, not on a friggin phone, and preferably not on a computer. It’s designed to be seen on a big screen, in a social environment, in a big dark room with other people. If you get to see people walking out of that big dark room, enlivened, uplifted, activated, then it’s worthwhile. That said, after all that work, you might get two men and a dog, you just can’t tell. I really hope that people do come out to have a look, because I don’t think it’s going to be in cinemas again for quite a while.

It is good fun. It’s what we do here. A number of our films have been made totally against all odds where they have had no government support. And people said, “You won’t be able to do it.” And through sheer will, [we’ve] got these things done. And this is another one where I think we can happily say we’ve given it a really good shot. That’s part of the fun of show business. It’s part of the addiction where if you can make people feel more alive, make them feel engaged with whatever it is that you’ve got on the screen, then that’s a very satisfying feeling, you know?

With that in mind, I’m curious what the identity of being an Australian filmmaker and supporting and nurturing Australian films means to you as a creative person?

HK: Look, my intention is not to support and nurture Australian films as such. Making films may do that, but that’s in some ways for other people to say. I knew what I wanted to do by the time I was about 12 or 13. I wanted to be a storyteller. And it was in theatre and acting and film that I knew that this was what I wanted to do. I’m incredibly lucky that I knew from a really early age what I wanted to do, and I’ve been able to just stay alive doing it. I am a very lucky man, a very happy man. I run to work in the morning and I have to be dragged away at the end of the day. So many people in today’s world work in jobs that they hate until they retire and I have been lucky enough to do something I really, really love since the 70s. I’m extremely grateful.

When I first started, I had to have a think about it. My mentor was a wonderful, fantastic filmmaker called Cecil Holmes, who was a member of the Communist Party of New Zealand. He came here and was sort of blackballed in the late 50s, in the McCarthy period. He made a couple of wonderful feature films called Three in One and Captain Thunderbolt when it was almost impossible to make films. His films were warm, socially progressive, humane narratives. And I saw that he didn’t become rich and famous. I had to think, “Why am I getting into this?” If it was to become rich and famous, then I was going to be in jeopardy. If it was to make films, tell stories and entertain people in exchange for being able to stay alive, then I was in a much stronger position. And I took the second option and have been having fun ever since.

What’s the thing that excites you the most about storytelling and filmmaking? What gets you excited and keeps you there at work all day?

HK: It’s the half shadowland, floating world of the narrative, of the drama of the dream, of the thrill of imagination. I fell in love with the disused film set with shadows that fall and stories redolent in the cardboard setting and the wooden props and that’s what excites me is the turning of crepe paper costumes and wooden guns and paper moons into a coherent dream world into which a third party – i.e. an audience – can enter and travelled through it to come out the other end even slightly more alive and sensing their own vivacity than when they went in. That’s what got me.