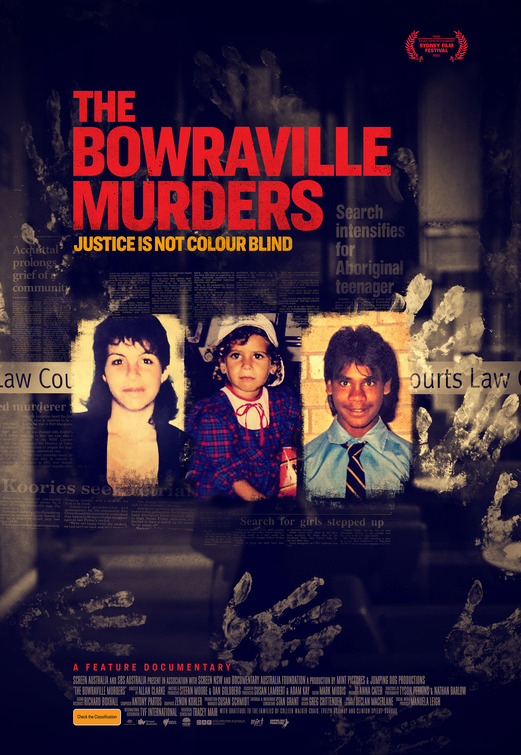

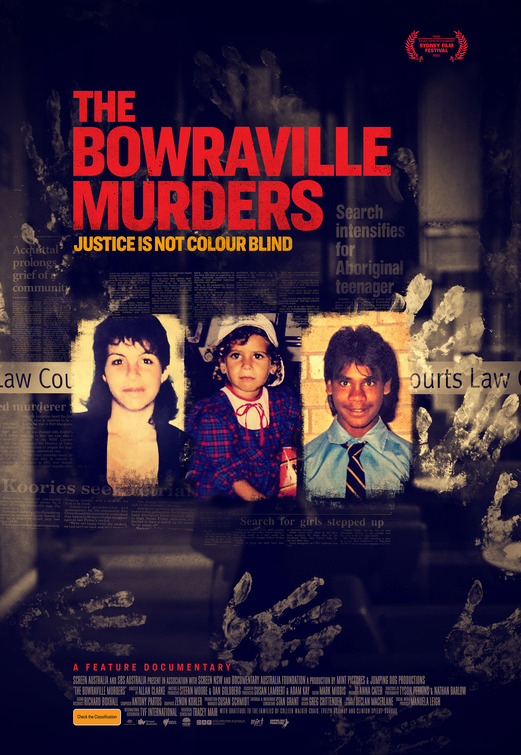

Allan Clarke is a Muruwari and Gomeroi man who has made a career as an investigative journalist. His work on the podcast series Blood on the Tracks won him a Walkley award alongside Yale Macgillivray. Allan’s work can be found on SBS, ABC, and Buzzfeed. His work has spanned across TV, print, podcasts, and with his highly acclaimed 2021 film, The Bowraville Murders, he transitions to the world of documentary filmmaking.

Ahead of the May 3rd screening of this important documentary at the Screenwave International Film Festival, Allan caught up with Andrew to discuss the making of the film from his home in France. This is an extract of an interview with Allan Clarke, with the full interview being published in the upcoming Australian Film Yearbook – 2021 Edition.

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following story contains references to deceased persons.

I watched The Bowraville Murders last year and was just quite stunned by it, and really impressed by how emotional it was as a film. Congratulations on bringing this story to life. It must have been a very difficult journey to begin with.

Allan Clarke: Well, thank you. Yes, it was a difficult period to get the film up, first of all, and also to ensure that the families were prepared to talk about the worst time in their lives, the loss of their children. And so it was important for me to ensure that they were first of all comfortable, but also they felt like they had a platform to speak openly and honestly, and to be in a safe space where they could be emotional. And so before we ever started filming, it was important that I spoke with all of the families and we would form a bond. We would speak a lot about what are some of the things that they wanted to say in the film.

It was interesting, because I didn’t have any preconceived notions of what the film would look like in terms of narrative or even having a shooting script that we would religiously follow. It organically happened after those conversations with the families. And, looking back at the media over the last thirty years, I think a lot of the times their voices were erased from a lot of the media coverage. And so essentially, this became an opportunity for them, at the end of thirty years, in this enormous legal battle to be able to speak in an unfiltered and raw way.

I felt it was really important that Australians and the world could see how the impact of not only having your child murdered, but also facing racism from the police and authorities in those early days of the first investigation, how that actually impacts these families, and they have to live with it every day, and what kind of grief and trauma comes with that. So it was important that we made a film that made people bear witness to what this and the police response has done to that community.

There has been this proliferation and real interest over the past decade in true crime stories. And one of the things which I noted was that unlike a film like The Thin Blue Line or Paradise Lost trilogy or The Jinx where there is this sense of closure for the people in those stories, all of those subjects are white. Whereas there is no sense of closure here for the families, for the victims. How do you manage the balance of knowing that there is no real closure within this particular story and trying to deliver what is really becoming quite a popular format of filmmaking of storytelling in true crime stories?

AC: I mean, true crime is such a broad term now and there is such a proliferation of it. Some of it is exploitative and some of it is very nuanced, it’s such a large spectrum. But also you want people to be engaged when they’re watching a film. Basically, I go through to pick some of the stronger elements of the essence of the true crime narrative to keep people engaged. Some of that is the forensic investigation, some of it is the whodunnit [aspect]. There are small cliff-hangers along the way, utilising that to keep people engaged. Also then, through the backdoor, having the audience actually bear witness to their grief and trauma is a really a powerful combination.

I’ve spent most of my career working on the intersection between Indigenous people and the justice system, and I found that being able to subvert the true crime genre to get people interested in an issue or issues within the Aboriginal community that they might not necessarily seek out has been a very powerful way to tell those stories and actually engage the public. And with this, I wasn’t interested in creating something that looked at the case forensically or the cases – calling Clinton and Evelyn’s cases forensically – because that had been done. There is a book, The Bowraville Murders by Dan Box, and Dan appears in the film. And there was some great work done before this film around the ins and outs of the cases, the kind of evidence-based stuff, the court cases.

I wanted to punctuate the film with that obviously, because people need to know what happened. But I think this is unique in that there is this raw emotion that is often left out of true crime genres because often there’s a focus on the salacious or the investigative stuff. We followed [the families] over the last two court cases up to the highest court in the country, and then they were rejected. There was this real sense of ‘Do we matter in this country?’ There’s a bigger issue here, a bigger question. The highest court in the country has just rejected us, basically denied us justice. What does that do to not only the parents of Colleen, Clinton, and Evelyn, but their families, their community? intergenerationally, how does that affect the younger people within those families? They’re the kind of themes I wanted to explore.

Before these children were murdered, the families were already facing issues within Australia, issues with the police, segregation. The parents of the murdered children all grew up on Bowraville Mission which was run by the government. They couldn’t even leave without facing potential violence or verbal assaults from the white community in that town, and that racial line is still very much alive. These are big ideas and concepts that we wanted to infuse in there, and why historically the justice system is like this with Aboriginal victims of crime.

I think in a way, we’ve been able to blend these two worlds in filmmaking or documentary-making, in terms of taking that true crime genre which is so popular and people really get invested in, taking the best aspects of that and interweaving it with this kind of raw emotional material that often is left out of that genre. So, hook them with the true crime stuff and then give them an entree into a world that they would never enter into, which is look, these people – they’re parents just like everyone else, but they’ve had to face these extraordinary battles.

That needing to tie up those thirty years – was that part of the decision of having somebody as prominent as Stan Grant there to help clarify the history in the film?

AC: That was kind of the most daunting thing: how do you sum up thirty years of this constant legal battle, David and Goliath battle really, between these three families and the Australian justice system. How do we do that justice? I think we did it in the film. But yes, there were a lot of things to consider, going into it.

And just going to your last question, yes, there is no sense of closure. I want the audience to feel like they actually went on that journey for thirty years. And this is where the families were really vocal with me in terms of what was in the film. They really wanted people to see the raw pain of it all, the grief, the trauma, the struggle just to fight this kind of battle, and then for it to be for nothing at the end. I wanted the audience to feel like they went through that, all of those highs and lows, it’s a real rollercoaster. And then at the end, the families are sitting at home and of course, they’re questioning what was it all for? Are our kids important?

And so the point that there is no closure at the end is a reality, not only for these families, but particularly for many Aboriginal families in many different ways. There is always a sense in the Aboriginal community that ‘Yes, we’re never going to get the justice or recognition we deserve’. And so I wanted people to feel unsettled at the end.

Because there are moments towards the end of film where it looks like that this is going to go their way and everyone is sort of exhilarated until they get to the High Court, because it looks like this man is going to be retried. And then it all just collapses, and that’s been happening since the early 90s when this took place, when the kids were murdered. So up, down, up, down. And so at the end, I think it was important that people felt unsettled, and that there was no closure. I wanted people to feel that so they could feel the way these families have felt. That was a really important thing for me.

Read Andrew’s review of The Bowraville Murders here.

You’ve been covering these kinds of stories for years and years and years. I understand there was a point where you decided to take a break from reporting the stories of Aboriginal deaths. What was the personal journey that you went on that you said, “Okay, this is a film that I want to make, and this is a story that I want to be able to tell?”

AC: Yeah, you’re right. I did take a break, I was very public about it. I did a piece for Background Briefing[i] about why I took a break. To be honest, I hadn’t really thought about it until the George Floyd stuff had happened. I had moved to France with my French partner, and I felt like I was taking a break from reporting but in fact I was actually really depressed, if I’m being honest. Because there were these things that I was just ignoring, I barely could get out of bed, no motivation. I just had nothing. I was cutting people off.

And then the George Floyd stuff happened in the States and I was watching a video of it and it sort of triggered something. I realised all this kind of emotion bubbled to the surface. I was kind of traumatised. I wasn’t dealing with the emotion that some of the work I do brings to me.

So I wrote, it was sort of a stream of consciousness. And yes, I realised in that writing, which I decided to publish, particularly for other people in my situation to understand that it’s normal. But yes, it’s hard to deal with this stuff, you have to have a self-care plan, you have to have a support network around you, because vicarious trauma does affect you.

After this, Bowraville had come along, and it was the first project after all of this mental health stuff happened, and I’d had a break. And so I felt like it was the right time, and I felt like I was able to recognise some issues. Like how can I mitigate that? Can I tell this story clearly? Because when you’re doing these stories, it’s not about you, so you have to be able to compartmentalise some of the trauma that is coming your way. Because it is about the families, you’re there for them, doing a feature documentary and having the time to spend with them.

It felt very empowering actually, to give them the agency about what was going in this, and we worked together. Their strength was so empowering. We had a safe environment to work with, we had a mental health nurse for people who were interviewing them. We made sure that everyone was having adequate breaks, because those interviews were kind of gruelling. And just spending time with them without cameras as well. All of that stuff helped me reset my boundaries in a way and how I approach these stories and work with communities to ensure that they have the best platform they can have to clearly tell their story. It’s interesting because it is something that often filmmakers or journalists or people in the industry don’t talk about, those impacts on the team that are covering these stories. This was a great way to show how it can be done where everyone is cared for.

What does it mean to be able to tell these stories as an Australian filmmaker, as a journalist? What does that mean for your identity as a storyteller?

AC: Look, I feel incredibly privileged to do it. For me as a storyteller, I feel it’s important that people are agile in terms of utilising all of the kinds of platforms that that we have. Long gone are the days where people would say, “I’m just a radio news journalist, I’m just a podcaster, I’m just et cetera, et cetera.” I just have a hunger to tell people’s stories and I’ll take whatever platform I can get, to be honest.

I feel like over the years, I’ve evolved to be able to go, “Okay, well, this story I don’t see as a feature documentary, I see it as television series or I see it as a podcast, so we’re going to do it.” Even though I’ve sort of dipped in and out of in the early years Indigenous affairs, most of my career has been around Aboriginal issues. The public apathy towards Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander affairs is insane in Australia, because there is a real silence around it. People just aren’t interested. So over the years, I guess my goal has been to work hard to capture that audience of Australians who don’t seek out Indigenous affairs issues. And to do that, I’ve had to kind of evolve my storytelling into ‘How do I utilise the mainstream things that are popular and have people engage with these stories’. That’s why I think working across multi-platforms, utilising something like the true crime genre means that I’m accessing a huge audience within Australia who are just kind of blown away by the fact that these things are happening in their own country and they don’t know if it’s happening. The response has been incredible. For me as a storyteller, it’s been incredible because that’s all I want to do. As a storyteller, you need people to be listening and watching and reading your stuff. That’s the whole point.

[i] Covering black deaths in Australia led me to a breakdown, but that’s the position this country puts Aboriginal journalists in – ABC News