Help keep The Curb independent by joining our Patreon.

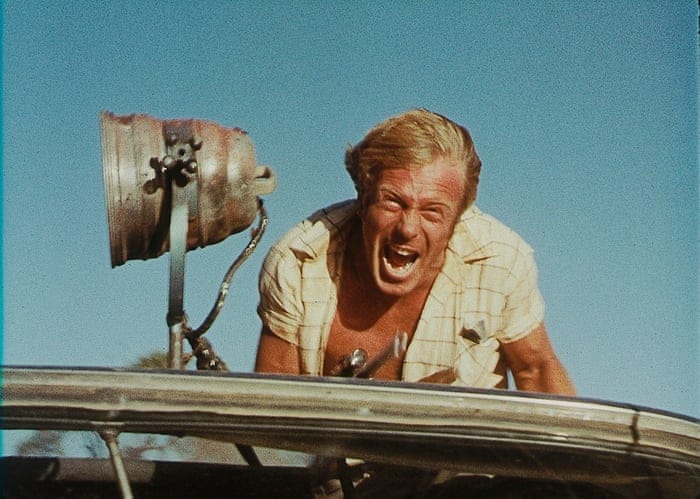

A confused and disgruntled producer, Sam Goldwyn Jr, was presented with a climactic scene from director Stephan Elliott’s third film, Welcome to Woop Woop. After Elliott’s brash, obnoxious, crass and crude film has rollicked through misheard musical numbers, farts and bonfires, ‘dog day’, and a show stopping bar top dance by none other than Rod Taylor wearing jumper-cable boots, it belches into a third act moment where Taylor’s grimy titan Daddy-O stands down seppo import Teddy (Johnathon Schaech), defending his dishevelled and destroyed town with a defiant defensive speech:

It’s too fuckin’ dry! Too fuckin’ hot! Too many bloody flies! But it’s ours! You might think that doesn’t amount to much… But it’s fair dinkum. It’s Woop Woop! I think that’s worth fightin’ for. Hands up all of youse who think that’s worth a fight!

Watching the speech now, it’s easy to notice that there’s something off about it. Taylor’s lips don’t entirely match up when he says ‘Woop Woop’, which in itself sounds a little strange. Sam Goldwyn Jr. felt the original line went ‘too far’ and didn’t make sense – as if the film itself wasn’t over the top and nonsensical enough –, forcing Elliott to take a sound bite from earlier in the film to cover up Taylor’s original line:

It’s Australia.

Additionally, pulling from the world of Mulligrubs, Elliott filmed someone else mouthing the line and superimposed their lips over Taylor’s chapped chompers.

It’s a line change that altered the meaning of the film. It actively removed the notion that this remote town of outcasts who believe they’re part of Australia, representatives of the common culture at large, were instead a group of walled off, isolated drongos who appear to be the exception to the norms of Australian society, ‘othered’ individuals who don’t represent white Australia as a whole. In a film that’s full of tonal shifts that demarcates audience member after audience member as the comedy lurches from absurd to satirical to light-hearted to complete raunchfest, this line change feels like the biggest shift of them all.

With Elliott’s second film, The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, he sought to celebrate a side of Australian culture that had been neglected on screen, and by highlighting the majesty of a troupe of drag queens driving through the desert, he married the city and the outback in one fell swoop. The nastiness in Priscilla is pointed and contained, where an instance of violent homophobia stings the Queens pub-set pageantry. When it came to making Woop Woop, Elliott had this to say:

I saw another side of Australia out there. I nearly got my head bashed in about four times. I thought, ‘Okay, hang on, we don’t put these parts in Priscilla, do we?’ But that really is what I wanted this new film to be about.[1]

And sure enough, where Priscilla celebrated the outsiders, the drag queens of the desert who brought glitz and glamour to the outback, Woop Woop made villains out of everyone.

Nobody is safe in Welcome to Woop Woop.

This is a film that’s eagerly reviled, despised, ridiculed, and slathered with the label of being one of Australia’s worst films. But it is also widely embraced, loved, and championed from the rooftops by the many who see a work of illness-fuelled genius at play here.

I’m part of the second group.

But before we get too far into the madcap brilliance of the Woop Woop-ites, I want to first take you on a journey:

In 1994, Douglas Kennedy released his debut novel, the pitch black comedic Wake in Fright-esque thriller The Dead Heart.

In the same year, fresh off his feature debut, Stephan Elliott slammed Australian cinema, and eventually the world with his follow up film: the Oscar winning The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert.

I started the year with the joyful abandonment of the little Queensland suburb The Gap, as my family made the slow saunter back to our home state of Western Australia by travelling around this broad, varied land. The journey would take us about six months, with my father’s intention to take in the four furthest points of Australia: Byron Bay in NSW, Wilsons Promontory in Victoria, Cape York in Queensland, and Shark Bay in Western Australia. Tasmania be damned.

My memories of the trip are vast, each providing a dusty tinge to my growing perception of Australia and what it meant to be Australian. As a shy nine year old kid, still impressionable and being moulded by the toxic racist streak that thrived in the Brissy Primary School I went to, this sojourn on the road, ‘learning from the land’ (as my teachers would call it) was exactly what I needed. If this sounds misty eyed and nostalgic, if not like privileged writerly wank, then I promise you that’s accidental.

In Longreach, my parents caught up with one of my sisters’ school teachers who had retired to the iconic location. The post-dinner discussion about kids dolls being equipped with anatomically correct genitals, moving away from the smooth curved dome that made the dolls feel almost futuristic and genital-agnostic, rings in my mind today. The alarm, outcry, and disturbance from the elders of society suggested a pandemic of paedophilia would sweep the lands upon the arrival of genitals on dolls. These same people would wring themselves into a knot in the decades to come with the increased awareness of transgender folk and who could use what bathroom. The fevered handwringing worry about the fracturing of society was tangible in the air that night, with the misguided parental concern colouring my perspective of such futures non-issues as ‘whether schoolkids should get the cane or not’ or whether Australia was, in fact, being ‘swamped by Asians’.

The hype and celebration of Muriel’s Wedding and The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert permeated through the air. I was far too young to watch these films, but it was impossible to not be aware of their presence in the world, with all the glitter, glam, and disco delight that they both wrought upon the Australian cultural landscape. ABBA and Gloria Gaynor were a far cry from Baker Street and Judith Durham, the soundtrack to our trip around Oz, but it became impossible to untangle the tumbled entwined nature of these pop songs, Aussie suburbia, and the sweltering heat of the red, dead centre.

As we made our way through to the Northern Territory, across the Gulf of Carpentaria, we brisked our way through small town upon small town, each with their own distinct accent, and each feeling as shut off and fractured from the other. When asked where we were coming from, it was safer to say the last town we visited, rather than ‘Brisbane’, for fear of being labelled ‘one of those city folk’. We were, of course, city dwellers, but we were also tourists, coming to a small country town, smiling with forced adoration over the souvenirs, criticising the cost of their Akubra’s, and laughing over yet another bag of ‘Kangaroo nuts’ bagged in a literal dried Kangaroo scrotum.

My memory lies to me now, but our stay in the Alice felt like it went for months. As a place of respite, I recall being forced to sit down with my often neglected diary, of which my sister and I had been told to complete every day as a form of ‘education’ due to the stretch of school that we would be missing, and was made to reflect on the journey so far. As I sit and write this, I’m awash with the memories of an Australia that embraced its fellow Australians with a feeling of eyeing caution, of judgement and disdain, a questioning gaze of ‘what are you doing here and what do you want?’. Unsurprisingly, the disdain that I recall from those who called the ‘outback’ home came from white Australians, almost furious that their homes were being invaded by other white Australians. I wonder if the rise of the ‘grey Nomad’ has made way for a further generation of disgruntled white Australians who sought the solitude of small town life, and the sanctity that it provided away from avocado toast consuming city dwellers.

At the park we were staying at, there was a resident who lived in his weathered caravan with his equally weathered Blue Heeler dog. I recall visiting him a few times, enamoured by the level of grime and muck that layered his clothes and skin, his mammoth size forcing an awkward manoeuvre into the caravan on a diagonal angle. At dusk one day, I watched as he chopped up a kangaroo tail for his dog, its tendons and sinew acting like an occy strap that might ping off any moment and slam an unsuspecting trolley boys eye out. He had an array of road kill stacked on his freezer each morning, collected after heading off into the night to scour the roads for kangaroos and emus that have had their heads collapsed by the pressure of a truck, or to relinquish their broken bodies that laid on the highway of their life as they breathe and gasp in pain, to clean the roads of the death and carnage, and to feed himself and his dog.

The smell reminded me of the puce like haze that hung around the XXXX refinery in Brisbane. It wasn’t death, but it certainly has never been in the presence of anything living. The buzzing neon sign stood proudly above the brick mausoleum that housed the death cries of the institution that is beer. As a child, I knew that XXXX was swill; a slurry of barley, hops, and yeast, blended in with the ‘pure local water’ of Brisbane, all of which, when combined, would make snails eagerly curl up and die instead of being submitted to death by way of a beer akin to ‘the dip’.

At each town, there was a new slice of ocker slang to add to my growing dictionary of Aussie colloquialisms. My ears twinged whenever someone referred to bathers as ‘togs’, but they gradually came to decipher the foreign version of English that was being spoken in rural regions, partly thanks to the education from this giant of a man. He taught me routine and basic phrases like ‘fair dinkum’ and ‘cobber’, and what it meant to ‘go off like a frog in a sock’, or why something was ‘as useful as tits on a bull’.

I didn’t know who Pauline Hanson was in the early nineties, but I certainly saw the impact of her rhetoric and beliefs throughout Queensland. I recall seeing a family of Indigenous folk in Cairns being yelled at in a grocery shop, being told to ‘get a job’, even though they were buying groceries just like everyone else. Returning to Perth, the jokes were of the same ilk, only with variations of the racist words I’d come to know. Joining them was a catalogue of cruel homophobic quips that became part of the playground vernacular, to be thrown like a barb when someone missed a shot playing handball.

Four years later, sitting in the Hoyts cinema half a k away from my high school, having bought a ticket to see Black Dog, and sneaking in to see the MA15+ rated Welcome to Woop Woop instead, this memory of the kind hearted behemoth, his dog, and his freezer chest of road kill came flooding back like a wave of unexpected nostalgia. Formative moments in our lives rarely announce themselves there and then, but that memory, married alongside the imagery of a mountain of empty Spam and XXXX cans, and the sight of a conveyor belt of carcasses, cemented an appreciation and adoration of the rugged outback Aussie bloke that I would otherwise have missed.

This self-centred walk down memory lane is less in service of testing out the waters for a potential biography about my childhood in Australia (gosh, what a bore that would be), and more scene setting for the continued defence that I have for Stephan Elliott’s third feature, Welcome to Woop Woop. As a stringent supporter of this bonkers and bizarre outback farce, I’ve long wanted to sit fellow critics down and shake them with the reality that yes, Elliott’s mania-driven, jaundice-pained production, is a work of utter, bonkers, genius. His scum-scraping prowess had managed to slather the buttered side of Vegemite toast with a level of affection for the obnoxious and crude ockerisms of the outback by way of a Sound of Music-level condemnation of the ‘cuntfaces’ of the world.

Putting it simply: Welcome to Woop Woop equally celebrates and condemns the politically incorrect and the communally archaic citizens of the world. It dances with them on the bar top with jumper-cable boots glitzing sparks across the jeering crowd, singing a chorus that calls them a bunch of outdated, micro-gene-pool swimming drongos who would shoot their dog and eat it for breakfast. There’s precious little line-balancing taking place here, with Elliott instead skewing towards a frenetic whiplash level of whirlwind mania that feels akin to a red-cordial fuelled child trying to play both sides of cops and robbers at once, and winning as each team.

The audience surrogate is Teddy, a chiselled jawed seppo played in a slice of pitch perfect casting with comfort and ease by Johnathon Schaech, a crim on the lam after a nondescript deal-gone-bad in New York. He heads to Australia to ‘find his birds’ after a bonzo back alley deal where he tries to sell ‘genuine, authentic, Australian cockatoos’ (Schaech’s pronunciation can’t help but carry a ring of ‘cock-er-two’ to it) goes south, ending with the birds being let loose in Manhattan, shitting over the New Yorkers who retaliate by pulling out their hand cannons and blasting the sky to smithereens.

Shooting on the streets of New York over three days to capture this rather pointless and extraneous introduction to the film, we see the unrestrained excess that Elliott was afforded by Priscilla’s infamy being blasted away at once[2]. Where Mick Dundee took glee in belittling the size of a man’s knife, putting Aussie’s as the land of the ‘stronger’ men, Elliott uses Teddy and his gun-toting kin as a boot in the side of the eccentric Americans. These are barely characters, instead grotesques that amplify the reductive mindset non-Americans have about yanks: trigger happy, violence-in-the-name-of-freedom supporters. These are Woop Woop’s first victims, and it’s clear that Elliott isn’t keen to stop there.

It’s no surprise that right off the bat Elliott upset and angered viewers. They expected more of the same from the director who helped cause a welcome celebration of the Australian film industry with Priscilla, but instead, Welcome to Woop Woop became cause célèbre, effectively condemning the future of Australian cinema to the dustbin of cinematic hell. Here was a man who managed to break into Hollywood with his Strine accented film, which nabbed an Oscar in the process, becoming the ‘hot new director’, only to ‘yes and…’ the dark side of Australian culture into a film that laughed and cheered alongside the characters it so eagerly condemned.

As the ‘hero’ of the piece, Teddy’s outclassed and out of depth in a world where variations on the English language are spoken, but rarely understood, where pineapple glazed kangaroo is devoured alongside copious amounts of canned Spam, and while sex is frequent and celebrated, ‘rule number three’ means you don’t sleep with your sister.

Australian cinema is replete with eager migrants finding themselves in too deep in a culture they fail to grasp onto, but in the catalogue of masculine imports being thrust into the outback to survive, Schaech’s Teddy is in a class of his own. He’s a world away from Gary Bond’s exhausted John Grant in Wake in Fright, or Walter Chiari’s optimistic Nino Culotta in They’re a Weird Mob, or even the wayward and lost troupe of refugees in Lucky Miles. The clear distinction is that Grant is British, and Culotta is Italian, with the asylum seekers being from Iraqi and Cambodian backgrounds. Teddy is very American, manufactured with all the cultural stereotypes we apply to the yanks of the world: ultra-confident, cocksure, arrogant, life-lesson spewing, self-satisfying ingrates.

While Teddy’s arrival in Australia is to play the role of open-eyed tourist, his import into the town of Woop Woop is less voluntary, being under the alcohol and drug-laden duress of his pepped up, Cherry Ripe devouring beau Angie (a masterful turn from Susie Porter). In some ways, Teddy shares a kin-like bond with John Grant, both of whom find themselves trapped in a region they fear they’ll never escape. But, unlike Grant, Teddy manages to flee his captors.

With Teddy having scarpered from his American worries, he sets off around ‘the land down under’ as a renegade tourist in a dusty VW van. Elliott delivers a meet-cute flooded with as much flesh as he can deliver, with Teddy taking a quick shower at a rundown petrol station, and the infectious and sugar-addled Angie glaring in giddy adoration at his well-maintained physique. Elliott’s camera caresses Schaech’s figure, showing us how easily Angie becomes addicted to Teddy’s presence, and we can’t help but swoon alongside her.

It’s a good third of the film before we even reach Woop Woop, with Teddy and Angie effectively fucking across the landscape of Australia. Elliott and writer Michael Thomas enjoy making us wait, giving us the sight of a prostrate, legs akimbo Angie spitting out memorable quote after memorable quote mid-root, from the iconic ‘part me beef curtains Teddy’, to ‘root me stupid’ and ‘fuck me dry’, all of which is joined by Teddy’s quizzical look when Angie screams ‘sock it to me!’ (Schaech’s response of ‘nobody says “sock it to me” anymore’ is a deadpan delight.)

Angie is a character driven by her own sexual hunger and desire, a notion that was thriving throughout the Australian cinema output of the late nineties, with films like Praise and Better Than Sex showing women in charge of their own sexuality. This is in stark contrast to the titillation of the seventies, where the bare bosom of women like Felicity Robinson in Felicity was less of a bid for sexual liberation for women, and more about sexual gratification for men. John D. Lamond’s output is best explored elsewhere, but as Australia’s smuttier Russ Meyer, his fascination with the bust was clear: the man liked breasts. For Stephan Elliott, Angie is a character conjured out of the drought of unsatiated sexual craving she’s lived with for so long, forming a rubber band ball of sexual frustration which positively explodes and pings off the walls after she witnesses Teddy’s chiselled physique. For her, Teddy is a bottle of Evian, emptied into the dust, and finally ending the sexual drought enforced by the confines of Woop Woop itself.

For some viewers, Angie’s voracious sexual appetite and her ferocious dialogue was too much, with the ‘beef curtains’ line carrying a graphic weight to it (even though Teddy’s Kombi has literal curtains with pictures of beef on them). Susie Porter was fresh on the Aussie film scene at the time, but delivered each eyebrow-raising line with the normalcy they deserved. Our manner of talking is an iconic aspect of our cultural identity, with phrases that sound nonsensical at first, but make complete sense as your brain wraps itself around them, and before long, you find yourself implementing them in common place chatter[1] . Porter’s delight at screaming ‘part my beef curtains’, or Daddy-O’s loud proclamation of fahfangoolah! shows Elliott and co. proudly leaning into the Australiana of Woop Woop, maybe even a little keenly trying to introduce a few new obscene phrases into the worlds vernacular, one upping the already established filth that permeates through our slang.

Just like Angie does to Teddy, Elliott hoodwinks the audience into expecting a certain kind of sex comedy, and then delivering a sucker punch of icky familial questioning, as Teddy meets Daddy-O for the first time. There’s no skirting round the bushes here, with Daddy-O jumping straight to the punch, demanding Teddy tell him if he ‘plugged his daughter real good’, and how good of a root she was. The open, frank, and jovial tone of the town makes this kind of otherwise private discussion feel as if it’s the norm – as if to ask, well, why wouldn’t Daddy-O ask about his daughters sex life? Especially if Teddy is going to be a new introduction to the gene pool of Woop Woop, extending the genetic variety with his American bloodline.

That knowledge and notion doesn’t make Daddy-O’s questioning any more comfortable, with the heat inside the corrugated tin pub being used as an extra torture device for poor Teddy. There’s something to be said about the masterful use of the searing Australian heat in Woop Woop that makes it feel like a tangible entity on screen, reaching out and making you sweat in your seat. Whether it’s the thick layer of red dust that smothers every characters pores and costume, or the sun-worn wrinkle-laden mug of Rod Taylor, poking out from his weathered and tattered Collingwood jersey, the production design by Owen Paterson, set decoration by Suza Maybury, costume design by Lizzy Gardiner, all work in harmony to showcase a cast of characters who have been built, shaped, and transformed by the scorching earth they call home. (Decades later, stories of systemic racism thriving within the Collingwood football club help inform the right-leaning mindset of Daddy-O just that little bit more.)

Rod Taylor’s ease and comfort is on fine display here. You’d hardly think he’d built a career overseas, having only featured in a handful of Aussie films, given how naturally he blends into the town of Woop Woop. There’s an ‘every man’ quality to Daddy-O, a nefarious one at that. He’s the kind of guy who’s all teeth, the rich, sleazy uncle or the misogynistic dad who bangs on about right-leaning politics a little bit too much, and how women have their place in the world. To some, Daddy-O might be endearing, but to many, he’s a thug, a brute, and a towering beer-filled man of a human to fear.

Stephan Elliott’s films are stridently political, with Priscilla working to bring the queer identity into the reserved homes of Australia. Woop Woop on the other hand was an acidic portrayal of everything that was wrong with Australian culture. Talking to FilmInk, Elliott said:

It’s a major attack on political correctness. You step back in time, and Daddy-O is a racist pig; basically he’s Pauline Hanson. It’s like a One Nation world happening back there. I played with a lot of taboos…it was great fun using the c-word, saying cunt for the first time really hard. For me, it was an exercise in political incorrectness, trying to cause trouble but with a sense of humour.

It then makes utter sense that Elliott would want to pillory the iconography of One Nation and Hanson’s band of zealots by casting Pauline herself in the film as the wife of Rod Taylor’s obnoxious Daddy-O. It wasn’t to be, with producers talking Elliott out of trying to cast one of Australia’s most notable racists. Hanson wasn’t the only politician that Elliott sought to cast, with his eagerness to get former Prime Minister Bob Hawke in a cameo performance also ending in failure.

These dream casting decisions further highlight how eager Elliott was to ridicule Australian culture and tackle what the Australian identity is. He’s on the record as saying that Woop Woop was ‘a hearty wave goodbye to an old Australia before political correctness came in’, and while that suggests an eagerness to offend the left-leaning folks who voting for Hawke and Keating, it also ignores the publicity statement that feels most apt for the film itself:

A film which will offend just about everyone.

Paul Byrnes said it best in his review for the Sydney Morning Herald:

It’s a film with a bizarre emotional polarity - nostalgic for the endangered Australian redneck, whom it actually despises. [3]

But the occupants of Woop Woop are less a species of endangered Aussie rednecks, and more a product of their own cultural bubble. Effectively becoming their own micro-nation, like a skewed version of the Principality of Hutt River, they live, quite literally, ‘off the map’ in an abandoned asbestos mining camp, where Daddy-O spews his own rhetoric about the rest of the world ignoring Woop Woop. There’s a grumble at some big wigs in Fremantle who wanted to pay the Woop Woop folks off, but really, what it boils down to is a Daddy-O-led guarded sanctuary where crude, unrestrained bigotry, and fervent racism is allowed to flourish.

Elsewhere, with the Oscar nominated Crocodile Dundee, tendrils of Paul Hogan’s Mick Dundee’s masculinity can be teased out of being a mere thread or two from the sun kissed desert comber Daddy-O. Mick is held up as a ‘proper bloke’, a man’s man, whereas Daddy-O is the menacing thug we find equally familiar. Both would be quick to reach for their belt-buckle in a domestic argument. Mick’s worldview plays as circle on the Venn diagram of Aussie blokes, overlapping with the actively xenophobic mindset of Daddy-O. If these gents had Facebook profiles, you’d be dead certain that they’d be slightly out of focus selfies popping up under threads about any topic they’d label as ‘snowflake’ material, all the while they lament the downfall of Kevin ‘Bloody’ Wilson or Rodney Rude and rage on about 'cancel culture'.

If anything, Elliott’s cognisant vilification of Daddy-O and the other brainwashed Woop Woop-ites is an equal condemnation of that species of ‘endangered Australian rednecks’ that Byrnes talked about. While Teddy sees right through the manic Daddy-O immediately, the rest of the town is oblivious, seemingly in awe of the pig who can stand on its hind legs, sing, dance, and talk with the rest of them. Instead of being horrified by Daddy-O’s manufactured Animal Farm, the other occupants are along for the ride.

And why wouldn’t they be? Most of them know no different. The rocky incline that encompasses Woop Woop makes a natural enclave akin to the same desolate sanctuary that Mick Taylor found in Wolf Creek. These individuals are outcasts of society, resolute figures who are far from being shadows of the genuine Australian townsfolk who litter the regions that many city folk only hear about on the news. They’re greatly unaware of the reality that while they live on tinned pineapple and spam, Daddy-O and his inner circle of sweat-laden, leather-skinned brutes have been devouring clean food from outside of Woop Woop.

That divide between the privileged (Daddy-O) and the poor (Woop Woopites) is not as cavernous as that that exists in reality, but it’s a glimmer of a reflection of Australian society as a whole.

One thing that unites the two sides of Woop Woop is the regular run of ‘Rogersun’ screenings. We hear of the fabled ‘Rogersun’ early on from Angie, with Susie Porter delivering a belter of a rendition of I Cain’t Say No:

Rogersun …you know, Rogersun Hammerstein. You know … (she sings) ‘I’m just a girl who can’t say no… I’m in a terrible fix…

and then thankfully get to experience it in full blown brilliance later on when the entirety of Woop Woop sits down to watch The Sound of Music, embracing the often misheard line: ‘what is it you can’t face?’ and shouting it out in unison.

There’s a subtle mastery to the inclusion of Rodgers and Hammerstein music that helps inform the time-capsule like nature of Woop Woop itself, with each inhabitant feeling like they’ve stepped right out of the 1950s. There’s more to seeing a town becoming stuck in a cultural bubble of Julie Andrews and co singing grand musical numbers than just Stephan Elliott wanting to give his film a killer soundtrack and some quirky musical moments. This is him building the notion that Woop Woop was once the last stop for film prints as they toured around Aus is one that’s barely touched upon in the film, but the logical notion of how the ‘Rogersun’ films ended up in Woop Woop, and the subsequent defection of Woop Woop from the entirety of Australia, feels organic.

When Angie’s introduced to Sonny and Cher, she recoils in disgust, reminding how eagerly Daddy-O wants to keep his kids and grandkids stuck in his 1950s mindset. Avoid the new stuff, only listen to the old stuff. Anything new is evil, and anything foreign must be destroyed. His anger fosters an isolation that breeds a different kind of culture, one where the lyrics of songs don’t match up, the names of the artists aren’t even right, where an anger-driven perspective of the world, one where their problems can be blamed on the existence of people they’ll never meet.

It’s a mindset that Australia has found hard to shake, and while we are continually told that we’re an open, empathetic country, the fact we’ve consistently voted in a right leaning, conservative government, that actively harms and affects the exact kinds of people that the occupants of Woop Woop would scorn and criticise for simply existing suggests otherwise.

In his review, Todd McCarthy called Welcome to Woop Woop a ‘nightmarish version of The Wizard of Oz[4]’, and he’s not wrong. Yet, instead of gaining a heart, a brain, and some courage, Teddy is dragged into the depths of despair, depravity, and a hedonistic lifestyle that should swiftly claim the life of any worn out individual.

Which brings us to Dog Day.

In the most inflammatory sequence of the film, the manic Woop Woop-ites engage in their yearly celebration of Dog Day: a day where they all take up arms and shoot all the dogs in Woop Woop dead. Teddy, manoeuvring himself into becoming an honorary Aussie, adopts a Blue Heeler, quickly becoming fast friends, only to have that blooming relationship cut short as his dog is slain dead as retribution after Dog Day. It’s an act that further divides Teddy and Woop Woop, and acts as the trigger point for his eventual escape from the town.

There’s something to be said about the horrifying repulsion the Woop Woop-ites have to dogs. The iconography of a bloke and his faithful dog means little in Woop Woop, where pups exist as scavengers, creatures brought in to fill the air with life, only to be slain on an annual day of canine carnage. They’re moving targets, ready for the youth of the town to practice their aim, and play a bit of ‘sport’. A lot can be said about people who fail to love or care about animals and the association with how they feel about the world at large, and it’s devoutly clear that the manner that dogs and kangaroos are despised in Woop Woop reflects the manner they despise the world that rejected them.

It’s quite likely that Teddy wasn’t the only one looking for the exit, with audience members likely being as inflamed by the carnage of Dog Day. The old Hollywood rule that says ‘don’t kill the dog’ is one that Stephan Elliott clearly rejects.

Yet, the act of Dog Day almost feels like Elliott is giving certain audience members the final push if they still find some kind of affection or affinity for the inhabitants of Woop Woop, making them finally recognise the depraved and cruel nature that the town operates. Or, Elliott just decided that losing even more audience members was the right thing to do. It’s as if he’s asking, have I lost you yet?

During production, he almost lost the cast and crew as well:

For Dog Day, art director Colin Gibson went into Alice Springs and did a deal with vets, asking them to freeze any dogs that had died. When they got out their first frozen dog, they discovered it melted in the temperatures in “about 3 minutes”, so Colin got the idea of cutting the dogs in half, so that they could be made to look like two dead dogs. So he got out the chainsaw and fired it up, and that, according to Elliott, is when they had cast and crew rebellion number three. “Stefan was going too far again, so all the frozen dogs were put back on ice and that was the end of it”.[5]

The entire production history of Welcome to Woop Woop is well worth reading about, given it’s quite simply one of the most turbulent and fascinating productions in Australia’s history. I highly recommend seeking out Michael Winkler’s excellent book, Fahfangoolah! The Despised and Indispensable Welcome to Woop Woop.

Personally, the notion of using genuine dead dogs, especially from an unknown origin, borders on the pale a little too much for me. My tolerance for the macabre and extreme is high, but when it comes to people’s companions, I find that aspect utterly grotesque in all the wrong ways. And while they didn’t decide to follow that route, to know that it came close is eye opening at the very least.

That notion alone makes me question my own ethics of being less than happy with the idea of dead dogs being used on a big budget film, while at the same time being – apparently – comfortable with the use of truckloads of kangaroo carcasses to film a pet food canning scene. Because the kangaroos were ‘ethically’ hunted – see the devastating documentary Kangaroo: A Love Hate Story for more on that – apparently makes the use of their tortured bodies as glorified props ‘ok’, when the truth is quite different. While I don’t have hard facts on hand right now, it almost feels like the iconic kangaroo is seen on Australian screens more as a carcass, or road kill, than as an actual wild creature itself. Maybe it’s just because sequences like this one in Woop Woop and the famed kangaroo hunt in Wake in Fright sear into your mind with impressive ferocity.

The array of dead dogs and kangaroos (all acquired from a local roo shoot), fits in perfectly with Elliott’s filmography, one that routinely operates in the death, destruction, and carnage of animals and their corpses. The exploding whale covering the town in gristle and rotting flesh, or the tethered turtle, walking a futile path around the hills hoist in Swinging Safari, or the belligerent sheep, dressed in drag in A Few Best Men, and even the unfortunate Chihuahua in Easy Virtue, smothered to death by a woman’s behind, all hint at a director who carries a certain level of disdain for the rest of the animal kingdom. Sure, Elliott’s owned dogs, but he also clearly loves getting a rise out of his audience by topping a beloved creature off on screen.

It’s not just animals that Elliott despises, as he seems to have a continued disdain for almost everyone, which is part of what makes his films so darn entertaining for me, as they continually carry a lack of care about what people will think of their final product. He’s a boundary pushing artist who has made a habit of exploring the aspects of society that many have considered utterly depraved or existing purely on the fringes of the world.

And it’s those fringes in Woop Woop that make it purely unique, bizarre, and utterly joyous. It’s what has me revisiting the film year in, year out, to immerse myself in a world that feels like a skewed version of a reality I once knew. I know that Welcome to Woop Woop isn’t a film that represents who the rural folks of Australia truly are – these are caricatures, larger than life and exaggerated to the supreme – but it’s also a film that reminds me the most of my time going around Australia.

Nostalgia drives so much of what we love in cinema and television. As film critic Alonso Duralde says about those who love the film Space Jam, did you see Space Jam now, or were you eight? We can’t help but approach the films that we grew up with with a level of affection and adoration that they may otherwise not deserve, and while we kid ourselves into believing that they are actually good films, the reality is often quite different.

That knowledge and reality won’t let me stop loving Welcome to Woop Woop. It’s a film that I skipped school multiple times to watch, relishing the manner it transported me to the caravan in Alice Springs with the man chopping up roo carcasses to feed his dog, or to the frozen 1950s mindset of Longreach where teachers who lament the loss of the cane go to die. The aspects of Woop Woop may repulse, or aggravate viewers, but Elliott’s keen desire to satirise what he saw thriving within Australia feels all too familiar to me.

Admittedly, there may be a broad section of Australian cinema that actively villainises the occupants of rural towns, making it into a wasteland of racist thugs and violent men who want to tear you into two. Welcome to Woop Woop is, at its core, a farce. It’s full of absurdities, eccentricities, and cultural tchotchke’s that should, ideally, not reflect the reality of Australia. But, coming back to Stephan Elliott’s statement about what he saw when making Priscilla, and the mindset he moved into making Woop Woop with:

I saw another side of Australia out there. I nearly got my head bashed in about four times. I thought, ‘Okay, hang on, we don’t put these parts in Priscilla, do we?’ But that really is what I wanted this new film to be about.

it’s hard not to break the realisation that what we see in Welcome to Woop Woop is what Stephan Elliott was seeing of Australia in the nineties. It’s a reflection of an Australia that I saw too, one that was pushed, morphed, and nudged by international culture into something that became its own beast. Woop Woop showcases a 1950’s mindset that seems to have captured much of the Australian population. While it’s charming to see an isolated world absorbed in Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals, it’s equally absorbing to see that world refuse the wheels of time, slamming on the brakes of change and demanding their own societal safety net.

And yet, while I personally find familiarity with the iconography within Welcome to Woop Woop, and Elliott felt he was reflecting the world he saw, there are just as many who gaze upon this film and see a narrative that actively tries to offend and ridicule the people of rural Australia. I can’t criticise those readings, especially given the identity of rural Australians becomes the foundations of how they see and interact with society at large, but all I can say is that what Elliott is presenting here is not an analogous representation of all of rural Australia. This is a heightened example of subset of people who seek isolation in the outback because the urbanisation of Australia is smothering their existence.

Yet, the reality within Australian cinema is that this kind of heightened representation of rural Australia has found extremely fertile ground. It provided the foundation for a horrifying critique of masculinity in the masterpiece that is Wake in Fright, where the remote towns of Australia have never felt as threatening, and later terrified in a different manner with the beastly Razorback. As I continue to cherry pick examples, we continue to see that the horror genre loves amplifying the more unsavoury aspects of rural life, with Killing Ground and Two Heads Creek (a film clearly inspired by the celebration and condemnation of right-leaning Australians in Welcome to Woop Woop, even if it was slightly hesitant to jump completely into the Bacchanalia of Woop Woop) both pushing the extremes of the rural identity. But, then we take a glimpse at the documentary Hotel Coolgardie, which presents an unsettling view of a rural pub, where the relative safety of two imported barmaids is constantly in question, and we’re left to ask: is this all there is?

That in itself is a loaded question, one that can easily be reputed by presenting harmonious and considered documentaries like Backtrack Boys and Zach’s Ceremony, which present the outback and rural regions as supportive and community focused fields that want to provide positive grounds for the younger generations to grow and mature. Additionally, I’ve personally found great comfort in Alina Lodkina’s subtle drama, Strange Colours, that plays like a deeply empathetic Kelly Reichardt-adjacent take on Wake in Fright. And, recently, the Christmas comedy, A Sunburnt Christmas, showed the struggler spirit of rural towns in a powerful manner, and Robert Connolly’s amplified that same struggler motif in the taut thriller The Dry.

Each of these stories, alongside Welcome to Woop Woop, represents different aspects of the white rural culture within Australia. They may not perfectly overlap with reality, but they reflect a world that feels, at times, genuine. Fiction, and to an extent, non-fiction, thrives on drama and the manipulation of reality to help create narrative intrigue, it just so happens that Stephan Elliott’s presentation of that is so absurdly over the top that it becomes its own frenetic beast, unable to be tamed by anyone.

It’s worthwhile mentioning that plenty of these narratives almost wilfully ignore the Indigenous Australian experience, and, when they do represent them, it’s often misunderstood or ill-informed. Jake Wilson’s interview with icon David Gulpilil is full of essential quotes, but the permeating reality is that many white directors neglect to appreciate the differences in Indigenous characters on screen, notably leading Gulipil to laugh about his characters fate in Walkabout, another rural-centric Australian fable. He does highlight though that there are non-Indigenous directors, like Rolf de Heer, who explore Indigenous characters from an informed and respectful perspective.

What we see on screen reflects how we think about a culture and society, and while there has been a complex layering of the white Australian identity on screen, a film like Welcome to Woop Woop eagerly builds up a pyre of cultural cringe to almost destroy any good will that has been built up. As I’ve mentioned, there have certainly been grand steps within Australian cinema to try and improve the image of rural towns, so much so that maybe both supporters and detractors of Welcome to Woop Woop can look at Elliott’s bizarre masterpiece and say: well, we can’t ever do that again, let’s try something different.

For me, Welcome to Woop Woop feels like the start of complicated reparations of trying to bond the right and left of Australia. My identity is that of being a white Australian. My father is an immigrant from England, and my mother is a first generation Australian, born to parents who emigrated from Scotland. We come from a history of white privilege, and as such, part of that legacy is knowing the relationship that white Australia has with the Indigenous Australians that this land was taken from.

It’s also knowing the danger of being stuck in an archaic mindset, where we fail to evolve past a generation that thought the White Australia policy was a good idea and should never have been removed. It’s knowing what continued isolation can do to a culture, and how that affects the minds of the people living there. To reference the opening of The Herd’s always timely song 77%, it’s knowing that what is shown here in Welcome to Woop Woop, is not only farcical, it was immoral.

That opening speech that Daddy-O makes about Woop Woop being worth fighting for comes after his outwardly racist tirade that slams Indigenous folk for not wanting the tainted asbestos mine land back after it had been destroyed, and how the cities – ‘Sydney. Fremantle.’ – have too many red lights, too many pollies, too many reffos, too much fucking chaos, in a manner that shows how wilfully ignorant Daddy-O is about the reality of the increasing modernity of the rapidly oncoming world. This isn’t to suggest that modernity brings progressiveness, but rather, through continued societal upheaval and changes, through protests and community movements, a gradual, glacial shift brings the overdue ideology of ‘equality’ to those who have been routinely denied its fruits due to an oppressive society.

Daddy-O, titan of the outback, stands as a figure who feels out of time, as if he arrived two decades earlier than he should have. It’s hard not to see Rod Taylor’s beetroot emblazoned face, with burst capillary upon burst capillary erupting after tirade upon tirade, standing alongside the equally beetroot emblazoned career politicians like Bob Katter or Barnaby Joyce, representatives of the areas that Daddy-O would have further isolated him and his fellow Woop Woop-ites from. Equally vegetable-adjacent is the noxious rhetoric spewing right-leaning politician, Peter Dutton, whose own words could be easily supplanted into Daddy-O’s dialogue, and yet, they’d feel right at home.

Great cinema holds a mirror up to who we are, and reflects back the possibilities of who we can be. It just so happens that the mirror that Stephan Elliott chose is broken, scratched, and covered in a black mould that infects everyone that inhales it. It’s Julie Andrews blaring guns on the top of a hillside, it’s a warning siren, an unexpected giant kangaroo from the void, crashing down and hastening an escape.

There’s an unbridled mania to Welcome to Woop Woop that feels like a rarity in Australian cinema, where a filmmaker has been allowed to unleash a creative cyclone that tears everything asunder. Its cinematic brethren are the equally maligned films like George Miller’s porcine sequel Babe: Pig in the City, and Baz Luhrmann’s melodramatic epic Australia; directing opportunities where creative freedom ran wild. As the decades have worn on, the ability for a filmmaker to weave a genre breaking and boundary pushing narrative on film has effectively dried up, especially from an Australian filmmakers perspective.

What we end up with is a homogenous library of cinematically similar films, mostly adhering to a prescriptive idea of what kind of cinematic experience the funding bodies want to craft a catalogue of. That’s another blanket statement that deserves further assessment elsewhere, but it’s worthwhile interrogating given the similar state of Australian film nowadays.

For many Aussie filmmakers, when they’re presented with a global smash hit like Priscilla, they take the opportunity to make a go of it in the US, but whether you stand on the love it or hate it side of Woop Woop, there’s something that deserves celebrating about Elliott’s defiance as a filmmaker, seizing an opportunity to make the exact kind of film he wanted to, even if Elliott has often hinted at a strong desire to go back into the editing room and craft a darker, deeper directors cut.

As I’ve been writing and revisiting this piece throughout the past few months, I’ve found myself revisiting Welcome to Woop Woop with greater frequency than usual. Dipping in, rewatching scenes, immersing myself in the humdrum radio chatter that washes over the town, castigating Woop Woop for leaving a renegade shopping trolley outside the school. I’ve grown to realise that there’s something fantastically comfortable about this film, something that prods and pokes my mind as each scene explodes in feverish fashion. While this might sound overly hyperbolic, I keep finding myself astounded by the creative genius Elliott and co. are working with, the result of which has seeped into my mind and stained the carpets. I could try and scrub it out, but I won’t, the red blemish is too appealing and I’ve grown to realise that it’s become part of who I am as a film lover, and as an Australian.

I love Welcome to Woop Woop for its mania and madness, for Elliott’s unbridled direction and decision making. For the manner that Jonathan Schaech, Susie Porter, and Rod Taylor, thrust themselves with vigour into their roles. For the creative decision to set a dead woman alight in a bonfire upon a pyre of XXXX cans, and then to have her fart when her corpse bursts. For the creation of cinematic images that are impossible to erase from your mind, hidden behind a tastefully presented set of beef curtains.

I love it for how it makes me feel closer to being Australian. As horrifying as the actions of Daddy-O and his cohorts are, I look at Woop Woop as a film that helps me address, ridicule, and reconcile with the toxic mindset of some of most powerful people in the country, and their many supporters. As a counterpoint to what’s on display, it also helps remind me that while Australians can be a fairly navel gazing bunch of people, we also do a stellar job of looking outwards and embracing the world at large, and celebrating our multicultural foundations. Yes, we’re a country that’s constantly at war with itself, about what it means to be Australian, about who we are as a community, but Woop Woop celebrates that war, leading to the realisation that Elliott’s intention of offending just about everyone worked.

There’s a chaotic harmony to Daddy-O’s enclosed community, one that carries the baton of countless other self-ostracized Aussies who have deemed the cities as being too restrictive, too caustic, too oppressive for their way of life. I think of the teacher in Longreach, away from the world they once were part of, helping mould and nourish younger generations with knowledge, and how they resorted to a life of solitude in a remote location, allowing a toxic mindset to simmer away, bubbling with distrust. Or the man with his dog, carving out a circular existence of scouring the roads for carcasses of our dwindling fauna, making a stew out of their bodies, and waking up the following day to do it all again. For some, that isolation is a necessity, a sanctuary.

It’s easy to point fingers, and to criticise, especially when the actions of the few are actively destructive and harmful, but as a rebuttal to that, Welcome to Woop Woop says, what other choice did these people have?

When I had the great opportunity to interview Stephan Elliott upon the release of Swinging Safari, the first thing I did was apologise for not financially adding to the box office of Welcome to Woop Woop. Look, I didn’t exactly boost Black Dog into becoming a massive box office success either, but I do regret not being able to throw money behind Woop Woop at the time. Its legacy now stands as a genuine cult film, with its lovers and champions standing behind it proudly, and that means more than any box office total can attest to. Elliott’s stature as an Australian film icon will always be because of Priscilla, but for the many champions, we know deep down inside it’s because of Woop Woop.

Watching Welcome to Woop Woop with 2021 eyes, I’m left with the tinnitus-like ringing from our Prime Minister about him being a leader for the ‘quiet Australians’, and I can’t shake the feeling that the people of Woop Woop are who he has in mind when he says that. Yet, if we drove him out to the crater in the desert, and left him there, then he’d get to see how loud and chaotic they really are.

And with that in mind, my relationship with Welcome to Woop Woop reflects my relationship with Australia. I’m conflicted. I love this country, and yet, I equally despise it for what it has become. I love Welcome to Woop Woop, and yet, I can equally loathe the manner that Elliott celebrates political incorrectness. Yet, unlike the horrifying path that Australia is leading itself down (inaction on climate change, human rights violations, denial of Indigenous rights), I can’t help but applaud, embrace, and champion Stephan Elliott’s multifaceted monster of a film, no matter how grotesque or horrifying it is.

After all, it's fair dinkum.

It's Australia.

Director: Stephan Elliott

Cast: Johnathon Schaech, Rod Taylor, Susie Porter

Writers: Michael Thomas, Stephan Elliott, (based on the novel The Dead Heart by Douglas Kennedy)

[1] https://www.filmink.com.au/rude-crude-fin-lewd-making-welcome-woop-woop/

[2] This is without even mentioning the expensive non-green screen aerial shot of a trained cockatoo flying near the Statue of Liberty.

[3] https://www.ozmovies.com.au/movie/welcome-to-woop-woop

[4] https://variety.com/1997/film/reviews/welcome-to-woop-woop-1117432692/

[5] https://www.ozmovies.com.au/movie/about/welcome-to-woop-woop#about