When you mention the word ‘Australia’ to anyone who lives outside this sunburnt country, there’s a fairly good chance you’re going to get a response about how everything there wants to kill you. Whether it’s spiders, sharks, or serial killers, there’s always something out there that is eager to unalive you.

Aussies are a hardy bunch, and with gusto and gruel they’ve created some truly intense films that depict some genuinely intense and memorable moments of horror. In honour of Shudder’s excellent 101 Scariest Horror Movie Moments of All Time list, I’ve conjured twenty Aussie horror films that will leave you unsettled, shaken and disturbed.

To help inform and curate the list, I threw open the question to Facebook and Twitter audiences to find out what they felt was the scariest Aussie horror movie moments. They varied from the ‘All Out of Love’ scene in Animal Kingdom, to moments in The Howling 3. Additionally, the ending of The Boys with David Wenham saying “Let’s go get her” got a mention, as did the machine sounds in Babe (if you know, you know). Finally, there was an honourable mention for the entirety of Baz Luhrmann’s Australia.

Let us know what your favourite Australian horror movie moments are in the comments below.

Spoilers within.

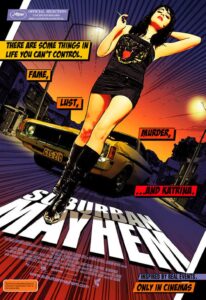

20. Suburban Mayhem

Paul Goldman’s Suburban Mayhem arrived at a time in Australian cinema history where crime dramas and youth stories dominated the landscape. It was an inevitability that the two would merge together, creating a vivacious and sinister domestic social satire that’s loosely based on Mark Valera’s murders. There’s a wealth of Aussie crime films that have truly unsettling and horrifying sequences in them that you can take your pick from – the bathtub murders in Snowtown are genuinely nauseating, the gun shop scene in Nitram unsettles with its sound design, and the box of torture devices in Hounds of Love hints at the trauma about to arrive) – but for me, the pinnacle of horrifying scenes that shook me to the core is the pivotal murder scene in Suburban Mayhem.

Emily Barclay’s AACTA award winning turn as Katrina is one for the ages as she gradually becomes the queen of her domain, enlisting the help of Kenny (Anthony Hayes) to kill her father so she can get an inheritance that is supposed to free her (and her brother) from their working class doldrums. In a genuinely unnerving act, Kenny lays into the father in the bedroom, all the while her toddler sits on the bed witnessing the crime take place. The screams of the child overwhelm the senses as blow after blow lands – all in the same frame. While all of these crime films will ruin your sleep, it’s Suburban Mayhem’s lack of condemnation for Katrina’s actions and her self-serving choices haunts the most.

19. The Pyjama Girl Case

Australia’s giallo output is slight, with Flavio Mogherini’s The Pyjama Girl Case being the rare entry to truly be able to lay claim to the title of being a giallo film. This 1977 Italian-produced thriller retells the tragedy of Linda Agostini who was found dead in 1934 in yellow silk pyjamas, fictionalising the narrative and bringing it into a 1970s context. Beaten and shot, Linda was then set on fire making identifying her difficult. This led to police setting up a public display of her body to see if anyone could help identify her. Mogherini’s film establishes a dual narrative that recounts Linda’s final days that gave way to her brutal death alongside the police investigation that took place to find the killer.

The practical effects that establish just how extreme the injuries that Linda sustained are effective, and during the film’s most horrifying sequence, Mogherini ensures to utilise every angle possible to amplify the discomfort for viewers. Midway through The Pyjama Girl Case, Sydney police set up a clear coffin for the public to come and help identify the body. While there is the occasional attendee who genuinely wants to help identify her, the majority of people are merely there to get a glimpse at a dead body. Mogherini amplifies the reactions from the crowd with everything from a fainting woman, to the seemingly endless line of men ogling and leering at her naked body. The peak of the disturbance occurs when a man slides underneath the box to look at every angle of Linda’s body. The climactic scene of Linda’s death is equally nauseating, but the dehumanising manner that the crowd views Linda’s body is truly one for the ages, especially when viewed in the context of the age of the true crime genre.

18. Next of Kin

Tony Williams eighties psychological horror Next of Kin is a film that doesn’t always deliver on the immediate shocks and scares, but its gradual atmospheric escalation conjures images and moments in your mind that linger in a way that attaches its tense moments with everyday objects. Take a bath for example, something we almost take for granted as a safe, inviting part of our home, free from anything that might cause unceasing terror. For Linda Stevens (a brilliant Jacki Kerin), the humble bathtub is just another aspect of the retirement home for the elderly that she has inherited after her estranged mother passed away, and it’s one that she likely didn’t give a second thought until a series of unexplained events start occurring in the home.

In one of the earliest scenes of Next of Kin, Williams stages a reveal so devilish that whenever I have a bath, I make sure the exhaust fan is on just so I don’t accidentally step on any submerged strangers in my tub. In a steam filled bathroom, one of the residents fills up a bath with hot water. Unable to see the bloated, purple corpse of his housemate beneath the water, the older chap puts his foot in the water, treading on the man. This early scene is just the beginning of the unsettling events that take place in the retirement home, effectively setting the tone for the tension that is to come with this cult horror film.

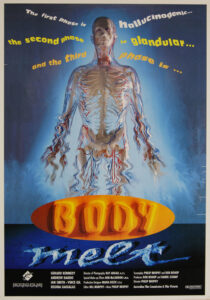

17. Body Melt

Philip Brophy’s early nineties shlock-fest Body Melt yaks a decade’s worth of dietary supplement pills and protein shakes all over Aussie suburbia in a sticky spray of green and yellow bin juice-like vomit. The plot, for what it is, sees the residents of harmless Pebbles Court receive a bunch of free body-shaping pills in the post. Billed as the path to creating the ultimate healthy human, the Vimuville pills instead cause a gut-churning array of hallucinations and a series of mutations that’ll make the Toxic Avenger blush. Everything from exploding penises (penii?) to eye-bulging face meltdowns to tentacles erupting out of a poor blokes face make Body Melt the ickiest, stickiest, gloopiest Aussie horror around.

While none of this is delivered in a serious manner, Body Melt still manners to unsettle with its extreme and effective body horror effects. In possibly the most absurd and disturbing moment, Lisa McCune’s Cheryl has a pregnancy which is established as a ticking time bomb. With everyone else turning to gloop, it’s just a matter of time before something gruesome happens to Australia’s queen of prime time. In a sequence that left me echoing the phrase ‘fuck a duck’, Cheryl takes the pills, instantly causing something truly horrid to go wrong. After calling for help and making her way to the bedroom, Cheryl starts to thrive around as her rapidly expanding belly grumbles and groans under pressure. Her partner runs in to help, only to be smacked in the face with a projectile placenta. Before you can say Alien, McCune’s belly explodes, blasting blood and guts over the room and opening up a tentacle mouth that sputters with gas. It may not be the most gruesome death in Body Melt, but it’s certainly the one that lingers in your mind long after the film is over. Poor Cheryl.

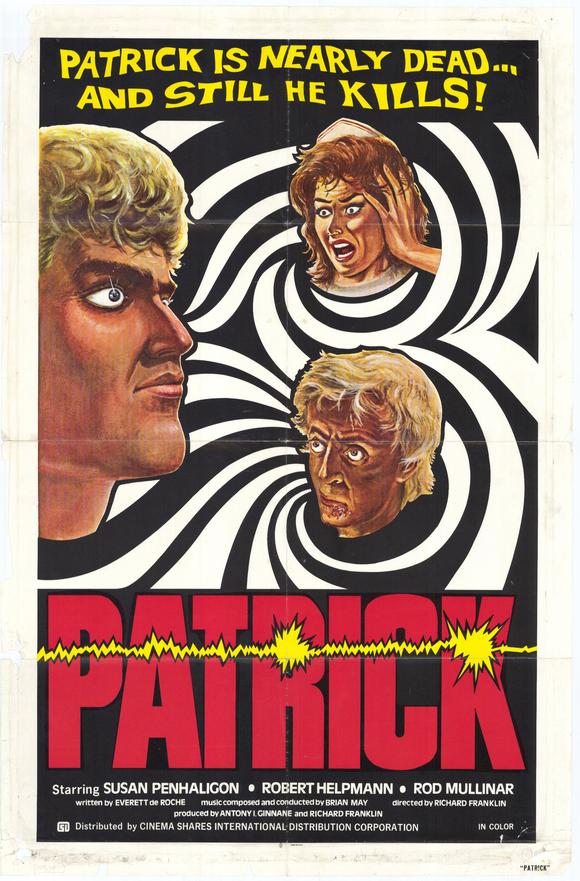

16. Patrick

Richard Franklin helped shape Aussie horror with two pivotal films: Road Games (1981) and Patrick (1978). With Road Games, Franklin utilised the sparsely populated road across the Nullabor to haunting effect, making a white-knuckle thriller that holds up perfectly. While I could have chosen numerous sequences from Road Games to fill this spot, it’s Patrick that leaves a mark with one of the very best jump scares in Aussie film history.

In a masterclass of mood setting and tension building, Franklin and writer Everett De Roche manage to escalate the anticipation that immobile Patrick (an effective Robert Thompson) will do something other than utilise his impressive telekinesis. Throughout the film, Patrick murders the Matron of the hospital, attempts to drown a doctor, and locks a man in an elevator. Nurse attendee Kathy (Susan Penhaligon) knows there’s more to Patrick than his comatose form suggests, and in the closing moments those suspicions are affirmed. Given the ultimatum to kill Patrick or save her ex-boyfriend, Kathy opts to inject Patrick with potassium chloride. Flatlining, Kathy and co believe Patrick’s reign of terror is over, only to be proven wrong when he leaps out of his bed, flying across the room and crashing into the medical cabinet. Franklin utilises the jump scare to perfect effect, delivering it right when the audience feels at their safest and leaving a truly shocking impact. It’s this horrifying moment that helps keep Patrick as one of the enduring Aussie horror genre entries.

15. Celia

Ann Turner’s Red Scare folk horror, 1950s political family drama Celia is a film that’s grown in appreciation over the years having been neglected for far too long. Rebecca Smart plays the titular role, a young girl recovering from the death of her grandmother who recalls the story of the Hobyahs coming to steal her away. At the outset, the horror initially appears to come from these mystical creatures, but Turner’s work reveals itself to be a film that has more interest in the cruelty of humankind.

Celia quickly becomes friends with her neighbours, the Tanners, who are members of the Communist Part of Australia. Eager for Celia not to mix with the young kids, her father buys her a rabbit which she calls Murgatroyd. In a masterfully layered approach, Turner creates a powerful metaphor for the societal fear of communism in the form of the Victorian governments ban on keeping rabbits as pets, forcing owners to hand over their rabbits to the zoo. Celia pushes back, but eventually Murgatroyd is taken by her uncle, Sergeant John Burke, to the zoo. After intensive petitioning, the Victorian government relinquishes and allows owners to keep rabbits with a license.

While the occasional appearance of the Hobyahs in Celia’s nightmares and hallucinations carries its own level of horror, it’s the rapidly extinguished hope that Celia experiences when she rushes to retrieve Murgatroyd from the Melbourne zoo. As kids galore retrieve their beloved pets off the ground, Celia searches amongst the colony of rabbits for her precious bun, only for the hope to drop completely as she discovers poor Murgatroyd drowned in the water trough. Turner keeps the camera on the body of Murgatroyd for what feels like an eternity, letting the pain that young Celia is experiencing to sink in. Sometimes the greatest horrors aren’t those of shock or violence, but the cruelty of life that causes such immense sorrow and anguish.

14. The Mule

In 2014’s The Mule, Angus Sampson and Tony Mahony plot a nausea inducing path from a simple concept of a drug trafficker, Ray (Sampson), caught returning to Australia with a gut full of heroin in condoms. Believing he has the drugs in his body, he’s detained by Australian Federal Police in a hotel room for four days, handcuffed to the bed as they wait for his system to pass the drugs. The script by Jaime Brown, Sampson, and one of the modern masters of horror Leigh Whannell, establishes quickly what is at stake for Ray if the police discover the drugs on his body and what will happen if he doesn’t deliver the drugs to his best mate Gavin (Whannell giving a sweaty and skittish performance). This threat level hangs over the film with each moment that the drugs aren’t discovered ratcheting up the tension of what might happen to Ray.

With a grate screwed over the toilet bowl to catch anything that Ray shits out, and a gut that simply can’t hold itself in any longer, he’s left with no other option than to swallow the drugs all over again. In a scene that you can only watch through your fingers, Ray lays in bed in the middle of the night as a guard sleeps in the corner. Slowly, Ray defecates each heroin filled condom and brings the shit covered parcel to his mouth, gagging and struggling to swallow them. One by one they go down in nauseating, gut-churning manner. Sampson’s performance is a full-bodied one, with his body shaking on the edge of vomiting and sweating like his life depends on it. It’s both desperate and disturbing, and while The Mule may not be a horror film, this scene is one of the finest moments of absolute tension in a modern Australian film.

13. Wake in Fright

Ted Kotcheff’s Wake in Fright is a masterpiece of maniacal masculinity that conjured the tonal shape of the Australian outback that caused a fallout of cinematic horror that has hung over the regions ever since. The unsettling opening shot details just how physically isolated the school that Gary Bond’s schoolteacher John Grant works at is, immediately setting the scene of just how purely desperate and hollow the experience of living in a societal desert can be. Splash a dash of booze and flick a couple of pennies in the air amongst a fervoured crowd of work weary blokes, and you’ve got yourself a recipe for disaster.

After flitting his earnings away on the giddy feeling of gambling, Grant finds himself trapped in The Yabba. As day woozily flows into night, Grant is swept up on one of the most horrifying and cruel events captured on screen: a night-time kangaroo hunt. Jack Thompson leads the charge of boozed up blokes bashing through the bush in their raucous ute, with Thompson leering over the spotlights with a rifle in hand, angling to find a bewildered roo to blast it out of existence. The resulting sequence is one of pure nausea, with an actual roo shoot being used as the backdrop of the experience. The fact that this kind of carnage takes place every night in remote Australia merely adds to the crippling unease of despair that permeates through every frame of Wake in Fright.

12. The Invisible Man

Leigh Whannell is no stranger to startling horror scenes, having created the Saw and Insidious series alongside James Wan, while also enjoying a welcome swerve into sci-fi body horror with Upgrade, so when it came to updating the iconic Universal monster The Invisible Man for a modern sensibility, Whannell was clearly the right fit. The 2020 The Invisible Man doesn’t muck around with getting straight to the fear, with Elisabeth Moss’ Cecilia creeping out of the house to escape her controlling and violent optics engineer partner, Adrian (Oliver Jackson-Cohen). It’s an unnerving opening that escalates with tension, with Whannell framing each shot in a manner that suggests that there’s something else there. This is a motif that lingers throughout The Invisible Man to devastating effect, with scenes often playing out with Cecilia just existing, yet the notion her abusive (presumed dead) ex is there, unseen, dressed in a suit that makes him invisible, is inescapable.

Whannell expertly employs jump scares to create a crescendo of moments that make The Invisible Man a modern horror gem. Whether it’s the gasp-inducing reveal of Adrian looming at the entrance to an attic as Cecilia throws a bucket of paint on him, or the kitchen fight where Cecilia endures a battle against the unseen figure, there’s something that will linger in your mind after watching The Invisible Man. Yet, none carries a greater weight than the crowded restaurant sequence where a distraught Cecilia meets up with her sceptical sister Emily (Harriet Dyer) to set things straight. Emily feels that Cecilia is being unjustly paranoid, but realises she is wrong in the cruellest way as a sharp knife flies into the air, slicing her throat, with the handle being firmly squeezed into Cecilia’s hands to suggest she’s the killer. Elisabeth Moss’ shattered look and broken exterior sells the moment even more, making it one of the most memorable and shocking murders in Australian film.

11. Relic

Natalie Erika James debut feature Relic is a tender and moving film that operates in the realm of allegory with the horror coming from the depiction of how dementia envelopes the ageing mind. Edna (Robyn Nevin) lives by herself, and when she goes missing it is up to her daughter and granddaughter to solve the mystery of what is happening to her. At the risk of infuriating the horror gods, Relic operates in the realm of ‘elevated horror’, utilising the genre to explore the impact of dementia by way of presenting the ailing mind as a haunted house, and by doing so it transitions into utter devastation and despair as the film progresses to a close.

As the gravity of Edna’s condition reveals itself, her granddaughter Sam (Bella Heathcote) finds herself trapped in the labyrinthine hallways of the house that Edna lives in. The knowledge that this is a genetic disease that will eventually claim her mind too makes the moment even more unsettling. Walls start to close in on her and turning a corner means doubling up on the path she had just undertook. The fear doesn’t just come from the situation that Sam is in, but how Natalie Erika James utilises an all too familiar ailment to ground the fear, presenting the climax with compassion and despair for her characters, with Charlie Sarroff’s cinematography amplifying that fear masterfully. It’s no surprise that Sarroff was picked up to lens the 2022 American horror hit Smile which utilises his skills in an eerily similar climax.

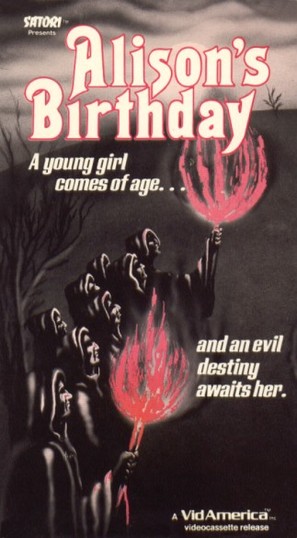

10. Alison’s Birthday

Ian Coughlan’s excellent eighties folk horror experience Alison’s Birthday is bookended by two seriously stunning moments of horror. Kicking off with the most effective oujia board sequence outside of The Others, Alison’s Birthday sets the scene for the doomed life of Alison Findlay (Joanne Samuel) by having a spirit who claims to be her father tell her to not go home on her 19th birthday or else something terrible will happen. Given this is a horror film, we spent the majority of the 97-minute runtime waiting for inevitability to strike and for the impending curse to fall upon Alison’s life. And what a curse!

Coughlan’s script never aims to hide the threat that looms over Alison’s life, with Alison’s surrogate parents, Aunt Jenny and Uncle Dean, pushing her to come home for her 19th birthday so the family can celebrate. The mystery evolves with the arrival of Grandmother Thorne, a 103-year-old woman who Alison has never met but is told to be her distant relative. The reality that unveils itself is that Grandmother Thorne is in fact merely a vessel to provide the human form for the Celtic demon named Mirna. It’s imperative that a sacrifice take place at the 19th hour of Alison’s 19th birthday so that Mirna can move from her ageing vessel into a younger body. The majesty of Alison’s Birthday occurs in the final moments which swerves in an unexpected manner. In most horror films, Alison would be able to disrupt the sacrifice and stop the transference of Mirna into her body, but this is no ordinary horror film. Instead, Mirna is successfully transferred into Alison’s body, with Alison being transferred into the body of Grandmother Thorne. It’s a heartbreaking and cruel moment as Alison screams in horror, realising that her entire life has disappeared as she now exists within a 103-year-old body, with Mirna existing in her body. It’s the kind of horror that makes the inside of your palms itch with fear.

9. Picnic at Hanging Rock

Sometimes it’s the unseen that unsettles the most, and with one monumental sequence of Australian cinema, Peter Weir did what Kotcheff managed to do for the sparse outback in Wake in Fright: he turned it into a haunted entity, transforming an otherwise beautiful vista into a field of unease and disturbance. The notion that the Australian landscape exists like a gaping maw that is waiting to swallow wayward inhabitants up is one that was heavily amplified by the cinema of the Australian New Wave, with Nicholas Roeg’s Walkabout equally dooming its characters to a desperate environmental fate.

A lot of the horror of Weir’s ethereal film Picnic at Hanging Rock comes from the dreamlike cinematography by Russell Boyd, the haunting use of panpipes, and the shattered cry from Edith (Christine Schuler) as she cries out after Miranda to not go further into a crevice in the rockface of Hanging Rock. Then there’s the blanket of the unknown that thrusts this film into the public consciousness like precious few texts have managed to do. The grand mystery of just what happened to Miranda, Marion, and Irma when they fell under a trance at Hanging Rock, and then disappeared as if pulled by some unseen force, has kept this film alive in the mind of everyone who has viewed it.

8. Razorback

Writer Everett De Roche managed to weaponise wildlife and feral beasts in the Ozploitation era to a memorable effect. In Long Weekend, Australian fauna fought back against the worst weekend holiday couple ever, and in Russell Mulcahy’s Razorback, he helped bring forth the grotesque and gargantuan mammoth boar that terrorised a remote Aussie town. Naturally, the real pigs of the picture are the brotherly duo of hunters, Benny (Chris Haywood) and Dicko (David Argue), who run a ramshackle pet food cannery. When American journalist Beth (Judy Morris) comes to the town to uncover the truth of Australian wildlife being hunted for pet food, she’s brutally chased down by the brothers, only to be torn apart by the ferocious titular razorback.

That sequence in itself is terrifying and masterfully shot by Dean Semler, who turns a subsequent extended dream sequence into a visual spectacle that stuns to this days, ultimately revealing the true disturbing nature of Razorback. Beth’s partner Carl (Gregory Harrison) comes to Australia to track her down, convincing Benny and Dicko to let him come on a night hunt in the hope that that might reveal her fate. The derelict brothers abandon Carl in the middle of the desert, giving way to a feverish nightmare where the skeletons of trees protrude out of the ground like Satan’s claws grasping for fresh souls. Then, as if the apocalypse itself is arriving, a tattered and terrifying horse skeleton emerges out of the desperate and dry lakebed. This sequence lingers for a painful amount of time, trapping poor Carl in an environment that would surely conquer him if he didn’t have the drive to find Beth’s fate pushing him through. In a cult classic full of iconic and horrifying sequences, it’s this one that kept me awake at night the first time I saw Razorback.

7. Sushi Noh

Horror fiends should take note of a name that you’ll be seeing more of in the future: Jayden Rathsam Hüa. With his first fiction short film Sushi Noh, he manages to cook up a gonzo, sticky beast of a film. Pulled from the surreal qualities of children’s nightmares, Sushi Noh sees young Ellie (Geneva Phan) living with her loner Uncle Donnie (Felino Dolloso). When he purchases a Sushi Noh machine to make dinner, things in the apartment start to take a sinister and nasty turn.

Part of what is so truly unsettling about Sushi Noh, and what easily makes it one of the most impressive and shocking horror short films in recent years, is the design of the sushi machine itself. Billed as a sushi-making device where the user pushes in the ingredients and it spits out a perfect sushi roll, the Sushi Noh machine is a beast of a machine where the user interacts with a Noh mask interface. With dark brows, foreboding eyes, and a menacing grin, the Noh mask is particularly terrifying, especially when it starts pushing out a moist sushi roll made with slimy fish and starchy rice. Jayden Rathsam Hüa delights in the horror of the machine and its culinary output, utilising its disturbing presence alongside the grotty walls of the apartment to amplify the nausea-inducing terror on display.

What pushes Sushi Noh over the edge into greatness is when the Uncle Donnie becomes possessed into tearing the Noh mask off the machine and bashes it onto his face. It’s as brutal as it sounds, and Felino Dolloso sells the violence of this moment beautifully. The mayhem and carnage that ensues over the 18-minute runtime is enough to put Jayden Rathsam Hüa on the map of Aussie horror filmmakers eager to push the boundaries of bad taste on screen. I can’t wait to see where his career goes from here.

6.The Moogai

Jon Bell’s short The Moogai atmospheric, familial-focused horror operates on the flipside of Sushi Noh’s gruesome horror. Here, Bell uses the genre to explore Indigenous stories and the intergenerational trauma of the Stolen Generation, entwining these themes with the story of young couple Sarah (Shari Sebbens) and Fergus (Meyne Wyatt) who are starting their life as a family with the arrival of their newborn baby. Bell drapes each scene in a cold, sterile uninviting blue sheen, amplifying the notion that there’s something nefarious lingering in Sarah and Fergus’ home. Before too long, we grow to realise that the darkness that looms is a malevolent spirit called the Moogai.

At first, it’s just Sarah who can see the Moogai. When she alerts Fergus to the fact that something is trying to steal her baby, he shrugs it off as a post-partum event, only becoming concerned for his young families safety when Sarah’s anxiety increases. Bell scatters the film with off-kilter moments of tension, like with a moment where an egg is cracked and a distorted fetus like thing drops out. Searing performances from Sebbens and Wyatt sell the drama of the script perfectly, and it’s Shari’s grounded and believable turn as a new mother that makes the closing moments the most terrifying of them all. As Sarah and Fergus fully realise the malevolent nature of the Moogai, they flee their house. An incident causes a car crash, killing Fergus and debilitating Sarah. It’s here, in these closing moments that The Moogai screams in the night a shout so loud that it reverberates through time, with Sarah trapped in her car as a field of spirits descend on the overturned vehicle to take her baby away: “Give me back my baby!” It’s enough to make you shake. If this is what Bell can pull on viewers in fifteen minutes, then we’re simply not prepared for what he will do with a feature length version of this story.

5. The Babadook

Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook is the finest debut from a modern Australian filmmaker to date. Building on her excellent short film Monster, Kent utilises supernatural horror to explore a story of grief, depression and trauma, as Essie Davis’ Amelia tries to raise her six-year-old son Samuel (Noah Wiseman) by herself. Samuel’s birthday is intrinsically tied to the death of Amelia’s husband, who died in a car accident as he rushed her to hospital while she was in labour, leading to a fractious relationship with Samuel where she almost resents his existence. When a mysterious book arrives at her front door, and Amelia reads it to Samuel, the Babadook arrives to upend their lives even further.

It’s that arrival that sends chills down your spine as The Babadook’s guttural, rattly and haunting voice creeps through the halls of Amelia’s decidedly out of place house (the masterful choice to use a house with a basement makes it feel like a home that shouldn’t exist in suburban Australia). Tim Purcell manifested The Babadook into existence, and with one word he conjured a major pop culture figure, a queer icon and a meme at once. That’s all thanks to the immediate otherworldly feeling that comes when you hear

Ba-ba-dooook dook dook

for the first time. There’s a reason why William Friedkin, a director who has crafted one of the very best horror films ever, was so completely unsettled by the film that he got behind it as a vocal champion, and it’s partially in thanks to that first appearance of The Babadook.

4. Killing Ground

Damien Power’s Killing Ground is a nasty piece of work. Aptly compared to Deliverance, Killing Ground sees a young couple heading off to the bush for a New Years break. When they arrive at their isolated campsite, they see that they’re not the first people there. What follows is a group of people – one the young couple, the other a young family with a toddler – being terrorised by sweaty, carnage-driven pig-shooters German (Aaron Pedersen) and Chook (Aaron Glenane) who want up their game by switching from wild boars to families.

Killing Ground is a film that lives up to its name, delivering an ultra-grim experience that sways between extended sequences of sustained terror to moments of explicit violence. A moment where the parents of the toddler are tied to a tree, with Chook taking pot shots at a can on their heads is enough to make your knuckles permanently turn white, or the climactic sequence which provokes questions about what you would do in a situation like this. However, the most disturbing and gut churning moments comes near the end of the piece when Chook picks up the toddler, slamming him into the ground. Unlike the other moments of violence in Killing Ground, this is an unexpected and shocking event that sears into your mind. Knowing that Power created the script after the birth of his first child adds to the grim nature of the act. A closing shot reveal that the toddler is still alive acts as a rare salve after the relentless horror that we’ve just endured.

3. Wolf Creek

If Wake in Fright established the possibility of fear in the remote desert outback, then Greg McLean’s maniacal debut feature Wolf Creek cemented it as an area that harbours men capable of great cruelty and horrific violence. One-time Better Homes and Gardens presenter John Jarratt immediately became a horror icon with his extremely-ocker Mick Taylor, an Akubra wearing figure that’s part Mick Dundee and part Ivan Milat. He’s a nasty piece of work, bouncing between endearing and endangerment in a second thanks to his uneasy laugh.

For British tourists Liz (Cassandra Magrath) and Kristy (Kestie Morassi) and their Aussie friend Ben (Nathan Phillips), their chance encounter with Mick initially starts as a jovial encounter with an eccentric Aussie bloke, before quickly devolving into all out mayhem with Mick revealing his murderous intentions. We know that soon enough one of the characters is going to die, we just don’t know how.

Instantly, McLean turns the film on its head, ratcheting up the intensity to the extreme, with Liz discovering Mick torturing Kristy in his garage. She manages to free Kristy, telling her to leave while she searches for a vehicle to get away. Returning to the garage, Liz climbs into a car to see if it will work, only for Mick to appear behind her, stabbing her with his bowie knife. Mick starts telling Liz a story about his time in Vietnam and the about of creating a ‘head on a stick’, the act of immobilising a prisoner and still being able to get information from them. In a one-two gut punch, Mick lops off Liz’s fingers, before severing her spinal cord. It’s a scene that plays like an Aussie homage to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre with the cut being heard and not seen, yet Mick’s explanation and Liz’s reaction causes a mental image so horrifying and disturbing that when I saw Wolf Creek on its opening night in Perth, this scene caused someone to vomit in their popcorn and another person to run out of the screening, never to return.

2. Lake Mungo

There’s a relatability at the heart of Joel Anderson’s Lake Mungo that makes the horror of its ghost story narrative all the more unsettling. Here, the Palmer family attempt to find reason in the aftermath of the sudden death of daughter and sibling Alice (Talia Zucker) who drowns while swimming with her family at a farm. For Mathew (Martin Sharpe), that means setting up video cameras in the house to record what he believes is the presence of Alice’s ghost. As Lake Mungo unfurls the tight knots of its mystery, we grow to know the personality of Alice, the hidden life that she lived, and the continual dreams that she would have about death, dying, and drowning.

The domesticity of the Palmer family and the tragedy they endure makes this feel a little too close to home at times. This is a feeling that is further amplified in one of the most gut-tightening and intense horror sequences in any ghost film ever. As the Palmer family discover more of the secrets of Alice’s life, they manage to discover her phone which contains footage of Alice walking along the shore of Lake Mungo. Anderson’s pacing of this sequence is unnerving, setting viewers immediately on edge as Alice walks further into the darkness. We know something awful is going to happen, we just don’t know what. When Alice is presented with a ghostly corpse that resembles Alice, albeit with a bloated, anguished face that looks like she does when her body was retrieved from the lake, we can’t help but try stifle a scream.

Lake Mungo’s stature in modern horror has grown over the years since its release in 2008, gaining a cult-like following that is only accentuated by the media-silence of writer/director Joel Anderson. The fact that he hasn’t made another feature since – and by all accounts, it appears he won’t ever again – only adds to the mystery of Lake Mungo. A genuine modern horror classic that will go on to inspire and horrify for decades to come.

1. The Loved Ones

When I came up with the notion of ranking some of the scariest moments in Australian movies, there was absolutely no doubt that Sean Byrne’s unhinged and genuinely deranged feature debut, The Loved Ones, was going to take the top spot. There’s a madness to this film that resides within Robin McLeavy’s inspired performance as Lola and John Brumpton’s doting father Eric, and it’s the manner that these two actors bounce off one another with concerning affection that makes the violence within The Loved Ones all the more exciting and memorable.

After Brent (Xavier Samuel) turns down the invitation to the school dance by Lola, he’s knocked unconscious by Eric and taken to their home. As Brent wakes up, he realises he’s tied to a chair and is surrounded by a makeshift school disco in the family dining area. A disco ball spins above, illuminating the pink dress that Lola wears. What follows is a series of escalating moments of domestic torture and terror, as Lola injects Brent’s voice box with bleach so he can’t scream. Lola attempts to feed Brent with a greasy fried chicken drumstick, leering at his face asking, “Is it finger lickin’ good?”, ensuring that you’ll never be able to look at KFC chicken the same way ever again*.

Bleach injected voice boxes and filthy fried chicken is nauseating enough, but it only gets worse from here for poor Brent. After he manages to escape, he’s hunted down and recaptured, with Eric and Lola pinning him to the floor by stabbing kitchen knives through his feet. Incapacitated for now, Lola carves her initials into Brent’s chest, and for denying her the chance to go to the prom, she sprinkles salt into the wounds. As an audience member, you’re just willing for there to be some kind of relief for poor Brent, as Xavier Samuel gives a performance that’s almost solely through terrified eyes.

But then Sean Byrne has his characters do the thing that makes you want to ask him “What the hell is wrong with you?” (which would no doubt be quickly followed up with a “Thank you for making me feel this disturbed”): Lola drills a hole in Brent’s forehead, aiming to lobotomise him by pouring boiling water into his skull. Byrne amplifies the tension and terror brilliantly as Eric holds Brent tight, Lola slowly approaching with the whirring drill. Thankfully, both the audience and Brent are given a reprieve of the torture as Lola manages to go so far as drilling a hole. Brent escapes, and the tables are turned on Lola and Eric. There’s a home-ready DIY vibe to the violence in The Loved Ones that’s given a layer of absurdity that makes you both recoil in horror and laugh with the utterly maniacal cruelty of Lola, one of the great screen villainesses ever.

*If you really want to be turned off KFC for life, do a double of The Loved Ones with William Friedkin’s Killer Joe.