It’s no secret that, like a lot of the Aussie film community, we at The Curb are very fond of Ben Mendelsohn. From his onscreen intensity and vulnerability to his offscreen shenanigans with meat pies and Zoom calls, he’s a bit of an Aussie icon. This is particularly true for the generations who have watched him grow from a wide-eyed boy to a surly young man to frankly terrifying Full Mendo and now get to see him explore the various opportunities Hollywood is finally bringing his way.

Whether it’s lead or a bit part, whether he looks feral or dapper, there’s a wealth of nuance and intelligence to a Mendo performance. They may not always be pleasant to watch, he doesn’t always survive the film or show – for a while there, I was like “Does he die in this one? He does, doesn’t he? Fucksake, Benjamin!” – but he’s always compelling and sometimes the most interesting person onscreen. Sometimes I have to remind myself that an actor has to take what he can get just to keep himself in smokes and games. And then there are projects where he’s the lead and the role is so rich and unlike anything he’s done before that as a fan and an Aussie, I’m so proud and so grateful to see him thrive.

One day he’s going to get that Oscar and it’s going to be for lead actor. It’s just a matter of time.

If you’ve only seen Ben in Full Mendo mode, here are six films to check out for his birthday. And no, he doesn’t die in all.

Mississippi Grind (2015)

Available to Watch Here:Before Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck slapped some prosthetics on him and snuck him into the Marvel verse, they cast Our Benjamin as co-lead in this lovely little indie feature. Don’t be fooled by the double-billing. This is Mendo’s movie. It’s a road trip, it’s a distressing exploration of a gambling addiction, and it’s also a sweet complicated love story between two men. No sex, unfortunately. There’s an open affection and delight between Mendo and Ryan Reynolds which makes this very much a bromance and a goddamned joy to watch when things are going well between their two characters. When they’re not, it’s deeply upsetting.

Boden and Fleck’s script is meticulously constructed, bookended with two scenes of exquisite characterisation, using a rainbow motif through visuals and names in the kind of random imagery that a quietly desperate person will seize upon as some mystical charm. Mendo gets to play a scene with the utter legend that is Alfre Woodward, just the two of them, bringing so much richness of subtext to what could be a throwaway interaction but isn’t.

Gerry is one of the best Mendo characters, a mild cat-loving creature who coasts from endearing to pathetic and back again. There’s a moment in a bar when he’s asked a direct question: the physical response, the sheer bigness and silence and expression Mendo conveys is one of those instances that remind you just how good an actor he is. It always strikes me as the perfect illustration of a sentence in Terry Pratchett’s Thud: “a gesture that said, far more coherently than he could, that there was the whole universe on one side and [he] on the other, and what could anyone do against odds like that?”

The film doesn’t take Gerry to the worst, it’s not an exploitative story. But there’s enough to make you understand and despair and want him to be better and save himself, to make you grieve for what he has already lost. The final scene always catches my breath, the symmetry and pacing and Mendo’s subtle expressiveness. I only wish he sounded Strayan.

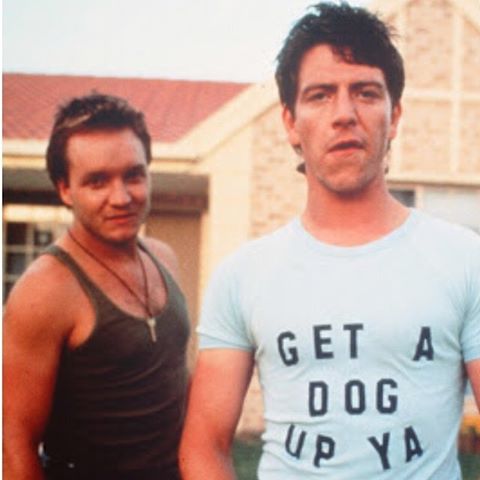

Idiot Box (1996)

Available to Watch Here:My first glimpse of Mendo was in a trailer for this. I had just arrived in Australia, and this sight of white boys hooning around deeply alarmed me. Teenage me immediately decided, “Oh no, I’m not watching that, it looks scary!” When I finally worked up the nerve two decades or so later, wouldn’t you know? It instantly became one of my favourite Aussie films. Soon after, I said as much to a friend, and this fully adult very sensible person bellowed “Maximum fear, minimum time” (the tagline) at an astonished me. Clearly a generational thing.

David Caesar’s second feature is filmed and edited at a frenetic pace that might frustrate some but makes my Nineties MTV brain so damned happy. The plot is a laser-focused exploration of white Aussie masculinity, specific to the Nineties era of disaffection and specific to the bleak suburban environs of Western Sydney as it was back then. But not just one type of masculinity: Jeremy Sims’ Mick is a very different young man to the dead-eyed bogan that is Mendo’s Kev with the apt surname of Madden. Kev is a live wire of aggression and misdirected ambition, too drunk and distracted by movie glam to fuck properly, an all too recognisable mess of automatic misogyny and easily offended masculine pride. Toxic af. Mick on the other hand is an affable guy who writes poetry, is apparently antiracist, neither repulsed by cunnilingus nor menstruation – bless him, we love to see it. You can tell these two have grown up together, locked into a friendship of affectionate bullying and uneasy loyalty.

Caesar’s script is such a great contrast of characterisation, the snarls and rhythms of the dialogue so familiar. Yes, Susie Porter has the most brilliant iconic line that cracks me up every time. Deb Kennedy and Andrew S Gilbert pop up in bit roles, darkly hilarious in their own separate ways. John Polson appears in a subplot that always wrenches at my heart. But of course the film belongs to the dynamic between Mick and Kev. It’s not hard to see one type of Aussie white masculinity as doomed, caught up in a very Nineties glam death-wish, set in opposition to the kinder type of Aussie white masculinity that will have a future of hope and happiness, even if material success seems still out of reach.

If you had told terrified teenage me back then that I would very soon see Jeremy Sims in his own production of Rosencrantz And Guildenstern Are Dead with the most thrilling concurrent staging of Hamlet at Belvoir, and that years later he would direct the perfect Last Cab To Darwin (2015), I would not have believed you. Mick might be the less flashy of the two roles but Sims’ quiet authenticity grounds the film and makes you care about their relationship. Mendo on the other hand is clearly having a riot with his performance, the beautiful late-Eighties boy now gleefully frayed into Nineties debauchery.

An Aussie classic for good reason. Can we have a Madman special edition, please?

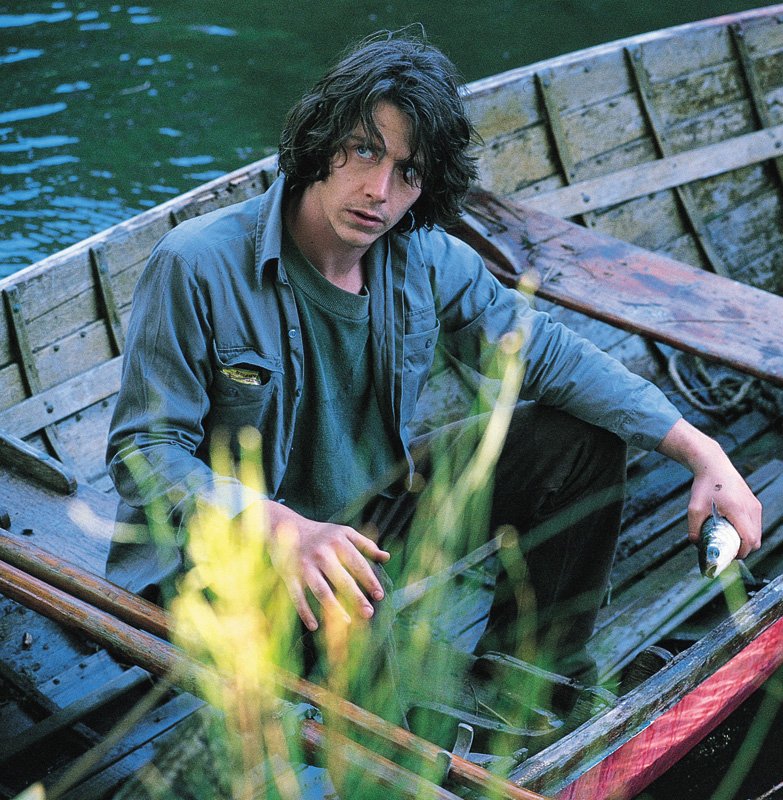

Mullet (2001)

Okay yes, I have a very soft spot for the Mendo-Caesar partnership, especially this double feature. If Idiot Box was an exploration of suburban white Aussie masculinity, Mullet is an exploration of small-town white Aussie masculinity. If Idiot Box was about stifled ambition and unattainable big dreams, Mullet is about failed ambition and learning to dream small. It’s a story of coming home and reckoning with old wounds, of strangulated white families who can’t talk to each other about the important stuff, of the weird tension in heterosexual jealousy, of sexual agency in a small town, of interracial relationships shadowed by white guilt.

I just love it So Much.

Sometimes I’ll go into a rewatch, wondering why I love it so much. And then that perfectly constructed script reminds me. It’s the smallness of the story set on the coast with very little natural beauty and no quirky lovable characters. Everyone’s very banal and ordinary in the exact way they are in country Australian towns. (I went to an unposh country high school, I know what I’m talking about.) The central character isn’t even a protagonist in the classic sense, he’s the catalyst for everyone else to change their stories. He has no form of his own, just a mass of resentful longing, and nicknamed with typical Aussie brutality for an unsavoury fish no one wants. That’s Eddie, my actual favourite Mendo character.

This is the era of Our Benjamin as surly young man. Eddie glares through shaggy dark hair, talks in cryptic monosyllables, hints at a big city career ruined by excessive hedonism, and tries over and over again to connect with people he once knew. At first everyone’s friendly and welcoming – well, mostly everyone. Eddie’s back in the pub, back on the footy team, back in the family kitchen. And then with one racially charged truth that connects eerily to the Adam Goodes implosion some twenty years later, he explodes every relationship around him. This isn’t a film about race but I love the depiction of a white Australian community who are so offended by the suggestion that they’re not that progressive. And the nexus character just happens to be played by national treasure Wayne Blair. Totally unassuming, totally underplaying, in a mere handful of scenes, but there. Listen out for the little exchange he has on the street.

Likewise, the women are fascinating. Eddie doesn’t even narrate his own story, that’s Kay (Belinda McClory) the writer who, like him, went away and came back again and now runs the pub for her dad. In this perfect little film about rural white repression, Kay is the only articulate person fully in touch with her own truth. She has this great conversation with Eddie about how she’s fucked pretty much every man in town, which he calls bullshit on, and she turns it around in an excellent observation of female agency in straight fucking. It’s such an interesting relationship of mutual respect and shared history. You get the feeling that they’re the only two people remotely alike in this place, the only two writers in this community of fishers and footy players and coppers. My favourite line in the whole movie is when Eddie says to her, “When you fuck someone, things are different. Forever.” I don’t think I’ve heard an Aussie man say that in a film ever. It makes him one of the boys closest to my heart.

Susie Porter plays Tully, the girl Eddie left behind. She’s fierce and tender and might be a bit of a mystery but the plot doesn’t devolve into clichés where she’s concerned. The formidable Kris McQuade plays Eddie’s mum and has probably the most eviscerating scene in the film. It physically hurts me every time, her vocal delivery, the actual line, and Mendo’s reaction and reply. Tony Barry as Eddie’s dad is an immediately identifiable blend of gruff warmth and judgement, and their dynamic is complicated by so much thorny expectation of how to be an Aussie man. There’s an incredible moment of missed connection between him and Eddie late in the film that makes me ache every time. Andrew S Gilbert as Peter, the brother, probably has the most difficult role in this ensemble, but he brings just the right amount of confusion and vulnerability and intelligence to what could have been a wooden non-performance.

The same could be said for Mendo as Eddie but really he has so much more to work with. All that explosive energy is here turned inward, glinting in malice. Amid the moments of affection and humour is a great deal of turmoil unarticulated. Eddie doesn’t know what he wants or how to get it but he knows he wants something, possibly everything. Mendo makes that a pretty interesting watch. Assuming you don’t want to slap the sullen out of him.

Here’s the weirdest thing about Mullet: it’s a stealth jukebox musical. The dialogue is gorgeously laconic, the quintessence of Australiana. None of these people, aside from Kay, are able to say what they really mean or what they really feel. But each of them has an ordinary moment when they sing along to a song on the radio or from their memory, and that is their truth. Even as a lover of musicals, I find that device a little bizarre but also delightful as hell.

If the ending to Idiot Box is ambiguous – I disagree – then the ending to Mullet is completely open to interpretation. Depending on my mood, it’s a domestic happy ever after or it’s heading out onto the open road, alone or together. Whichever way, I’m here for it. And sometimes I like to dream about a spiritual sequel, David Caesar writing and directing a film about an older version of Eddie who has to cope with what it means to be a man in today’s Australia. Silver-haired Mendo being all laconic and watchful – not regressing into bigotry, thank you – in that same or similar small coastal town, maybe with a queer kid. Make it happen, Caesar, kthxilu.

The Land Of Steady Habits (2018)

Available to Watch Here:Ben Mendelsohn as lead in a Nicole Holofcener film on Netflix? Get the hell out, what glorious combination of events made that happen? Well, I know how it happened but still I’m amazed it did.

Mendo plays Anders, a corporate hotshot who decides to retire and leave his family and their affluent community in pursuit of a new life and some sort of happiness. He picks up women at Bed Bath And Beyond, gets high with teenagers, and tries to repair his relationship with his son. On paper, this makes my eyes roll. But on film with that particular cast and that particular adapter-director, it’s a weirdly compelling experience.

Holofcener and Mendo walk a fine line between portraying Anders as a self-absorbed dick and a lost soul. He is one or the other at various points in the film but mostly he’s just trying to figure out what his new life looks like. And of course he has to try and explain why to his former friends and his ex-wife and possibly his son, too. For me, the relationship between Anders and Preston the son, played by Thomas Mann, is the most fascinating. The push and pull of longing and resentment is forever sharpened by the possibility of abandonment, of either one choosing to walk away and never see the other again. Which makes for at least one deeply emotional moment where I fully teared up and had look away and clear my throat.

It also doesn’t hurt that Nicole Holofcener shamelessly puts Mendo in a deep blue sweater more than once, filming him and those eyes in some gorgeous moments. Bless her. Still I wish she could have directed him in a script and story entirely her own with all her fine-tuned explorations of relationships in their tenderness and absurdism. And let him stay Strayan. I’d love to see that.

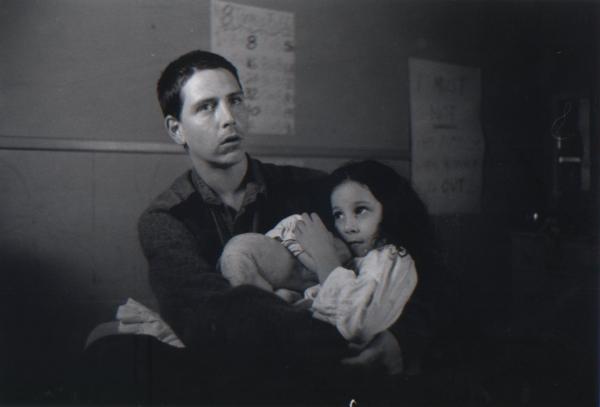

Amy (1997)

This was my first Mendo film. Every time it was on television, my aunt and I sat down and watched it all the way through. Of course at the time, I was crushing on Nick Barker as the dead muso dad because I’m shallow like that. But weirdly enough, it was Mendo’s name I remembered. Probably because every time, my aunt said: “I like that Ben Mendelsohn so much, he has such kind eyes.” No, she’s never seen Animal Kingdom (2010).

In the Australian film canon, nobody does Nineties Melbourne suburbia quite like Nadia Tass and David Parker. In the strewn back streets and in the houses of dilapidation or cosiness, their films have a compassion and affection for ordinary people living their daily lives with no great ambition and no particular self-awareness. There is always some violence and trauma either in the fore or background, but somehow I always know that everything will be all right in the end and so I’m happy to go on the journey with them, following where they lead.

Amy is a typical example of that suburban story, even though it begins in the visually stunning and very Drover’s Wife setting of a parched paddock. Rachel Griffiths plays Tanya, the widowed mum of eight year old Amy (Alana de Roma in her only screen role) who hasn’t spoken and apparently can’t hear since watching her rocker dad die onstage. Tanya is struggling with her own grief and damage, trying to help Amy and keep a roof over their heads, and keep child protection services from splitting them up.

When they move to an extremely dodgy part of Melbourne, the neighbours all with their own stories of hardship and eccentricities form a diffident sort of community around them. Mendo and Susie Porter play siblings here, which is a bit disconcerting after Idiot Box and Mullet. Robert has muso aspirations but seems also to be primary carer for his sister Anny whose schizophrenic condition is mined for a few laughs and pathos.

Little Amy’s response to Robert’s music creates a mutual curiosity that develops into a trust which is absolutely precious to see. Mendo’s role is supportive to the performances of Rachel and Alana, an aspect I love in its own right. Robert is snarky and sincere and not creepy at all, and Mendo still gets to be insolent at a cop or two. There’s a great bit where he lolls on a step and serenades the street with ad-libbed lyrics. I cherish that bit and the cuts to the neighbours’ reactions.

Look out for a few familiar Aussie faces, including the excellent Kerry Armstrong in a subplot of domestic violence that shakes me to the core every time, particularly the reaction of the son. It’s a perfect heartbreaking detail of characterisation, so true to life and so typical of a Tass/Parker film.

Songs function as an almost magical realist device in this story, and make for a deliciously absurd sequence amidst the darkness and healing of the final act. On every rewatch, I think it’s no wonder I love this film so much. If you’re open to it, the Tass/Parker blend of whimsy and realism is such a gift. I’m so glad Mendo got to be part of that on more than one occasion.