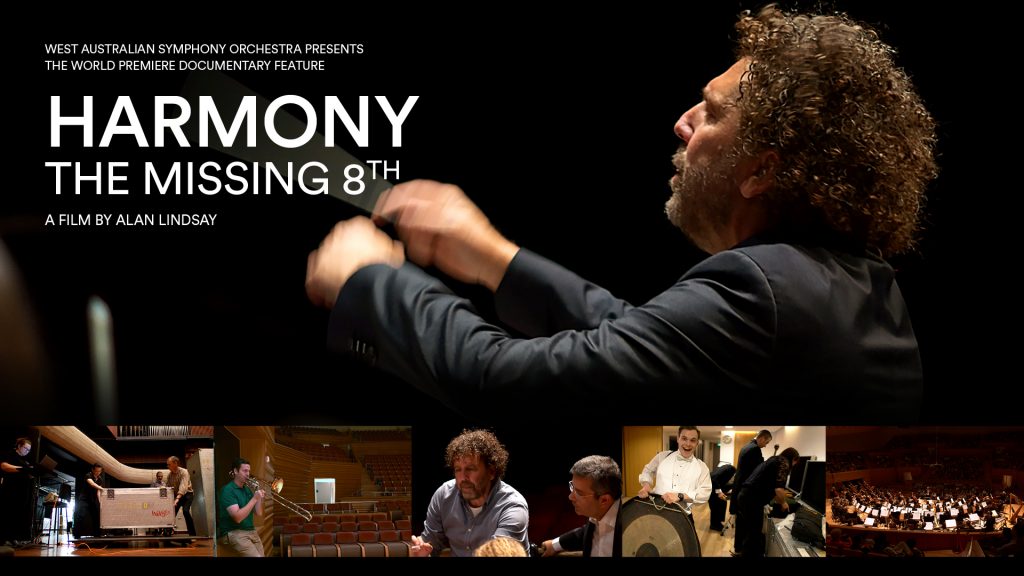

Harmony: The Missing Eighth is director Alan Lindsay’s three-year journey with the Western Australian Symphony Orchestra (WASO) as they embark on a journey to perform Mahler’s 8th Symphony. Through frustrations and triumphs, WASO find themselves in China, performing in glorious concert halls. Along the journey, Alan documents the struggles that WASO go through to practice and perform the symphony, while also (most importantly), clarifying with power and passion the grandeur of the orchestra at full force.

In this extensive interview with Alan, Andrew asks him about the process of filming a cross-continent documentary, the needs and demands of showcasing the brilliance of music on screen, and then finally exploring the role and the support of the arts in Australia, with a keen focus on the culture of Perth.

Harmony recently screened at the Windsor cinema in Perth, with a future release to come.

The interview starts off with Andrew and Alan lamenting the frustrations of computers, before segueing into the difference between film and digital stock.

(This interview has been edited for clarity purposes.)

Alan: I know people who say, ‘I like the old days of film’. Well, I don’t! I’ve been doing this now for 52 years, and I’ll tell you what, working in digital and working on computers is a bloody sight better than going out and having a can of film that barely ran for five minutes.

Andrew: I can imagine it’s got to be frustrating. You go out there and you think you’ve got a shot, and you don’t know until it gets developed.

Alan: And you just have no length. Even shooting 16 mil, the longest you could get out of it for something that was handholdable was 15 minutes.

Andrew: I imagine that makes life a lot easier when you’re filming a documentary, having digital… you can have as much as you need.

Alan: This is the sort of observational stuff that we used for Harmony. I would shoot three concerts, and we’d be cutting all three, the same piece, together. I’d set up a lock off camera, and then everything else was either handheld or on a monopod because we would be walking amongst the audience, and I was allowed on the stage. So, it was really masses of footage at the end of three years of shooting. When we went into the edit, I think we had something like 1200 hours. But then it’s all about going through and finding the drama, and half the time the drama turns out to be a shot that’s a bit soft, but you have to use it, because it’s the drama. The way observational documentaries fall apart is where people go ‘oh, that’s a nice shot, we’ll put it with that nice shot’. It’s all about capturing the moment. Not that I’m saying it’s (Harmony) full of lousy shots because I shot it, I would never say that!

Andrew: It’s a wonderful looking film. What I was really impressed by is how you managed to inject the audience into the auditorium of, not just the Perth auditorium here, but in China as well. We get this impression of sitting there with the audience which is a hard thing to do.

Alan: I shot more than one day, but in China I couldn’t as it was all one event. Here, I would shoot from the orchestra pit, I would shoot from the audience, over the shoulder, and I was down on the stage at the back of the brass section, which means that working with your earplugs in because you can’t hear a thing. But putting it all together, it always came back to that thing of when the music’s playing you got to feel like you’re there.

I used to be in a rock band as a jazz drummer, I played session music for a long time when I couldn’t really play with a band because I was filming and you’d never be available when you’re supposed to be available. It was always heavy rock, country surf and whatever. That’s my musical background. So gradually over the years I’ve got to listen to more and more classical.

This just changed my life as far as music was concerned, because to be sitting there in the middle of a piece of Mahler… was just crazy, really. And it’s just fantastic. And so I was trying to get that as well. That’s a sound thing too. By combining the rehearsals and the pieces in concert in the rehearsals, was all stereo mics placed around the place really close in concert. There’s a Decca tree hanging above the stage and going through boards and what have you, but I wanted the scrapes and scratches and the knocks and the noises and things in rehearsal. And then when you get into the concert, you had something to uplift as well. But it was just fabulous being so close to it.

Andrew: I can imagine. I’ve seen a wealth of music documentaries, not so many that are focusing on classical music, but what I’m grateful for is the manner that you actually let the pieces sit there in the film by themselves, not in their entirety, but, we get a fair chunk of the actual music itself. From my understanding, sometimes directors or editors are a little bit too afraid of just letting the music sit there like they’ve got to cut to somebody talking. Was that an active decision for you?

Alan: Oh, yeah, absolutely, right from the first proposition. I started off, I thought I’ll do it with a small crew, there’ll be three of us, we can get in and do it, and the very first day of doing that, I realized I wasn’t gonna get it. I had to be on my own. You can’t move around with three people. You can’t. And you’re restricted… if you leave where the recorder sits.

And from then on, I shot everything alone, the sound and the picture. I took that risk, because you needed the music to have its own sense of build and its own sense of drama, and to be the reason why these guys were going through the pain we are going through. But the last thing I needed to do was just an agony aunt film, sort of like a copy of the BBC opera (The House series) one where it’s fascinating for the first couple of weeks in Covent Garden were struggling, but after that it was the same story over and over again. ‘We haven’t got any money’ oh. ‘What do we do?’ ‘Well, we have to find some money.’ And even that doesn’t last too well through 89 minutes, so the music had to really, really work.

Andrew: As you’re saying it’s something that we’re familiar with, the need for arts to have more money, but it gets to show what they’re actually fighting for. And why they’re fighting for it as well. There is an emotional impact of it. There’s a moment where they’re talking about the quiet of the music and the loudness of the music.

Alan: That’s fascinating. Asher (Fisch – conductor) says, ‘anybody can do loud, quiet as where you really know whether or not (they can)’. And that’s all part of his opera thing too, because he has to have those quiet moments, or the thing (the emotion) is not going to come in like it should come in. He really cares about those (moments). The light and dark.

Andrew: What’s it like sitting in so close to all of that music, in the pit? As you’re saying, if you’re near the horn section, you got to have earplugs in…

Alan: I’ve got stereo plugs in anyhow, because I’m monitoring the sound as I go. But I had to put another set of headphones.

Andrew: Is there an emotional impact for you?

Alan: Oh, God, yeah, yeah. It’s interesting, there is nowhere in the concert hall that is not acoustically perfect. And the architects will claim that was how it was designed, but I suspect this just the coincidence of having that layout to try and get as many seats in the round, and opening up the orchestra pit, and having that enormous organ. The organ acts like a kind of absorber as well, it doesn’t deflect from the back of the stage. It’s just perfect.

When they’re projecting film in there, they put the film on a mono, stereo won’t work. That’s how perfect. When you’re up where the organ seats are, and shooting around there, the guys that you find up there who pay the full price, but go and sit up the back are all real musos, and that’s where they reckon you should be because no matter where you sit, it’s going to be perfect. But only up there do you get the actual impact to the sound hitting your chest.

Andrew: I’ll keep that in mind next time I visit there.

Alan: It really is an impact. And when you get Asher performing those gymnastics and what have you, you’ve got that visual effect as well as the (music) hammering you. It’s marvelous.

Andrew: When you embarked on documenting this story, did you have an idea of where it might go?

Alan: I do a lot of work in China, I’ve been working in and out of China since 1987. And then the last 10 years, up until roughly two years ago when COVID started, I was in China several times, just about every month, I’d be there for a week or so working on projects. We do animations as well, for big theaters. We did a 48-meter-long animated wall for the Savannah in the back of the Natural History Museum in Shanghai. (I had) an understanding of how China works, so I could understand that relationship with WASO, and I could understand the incredible significance of China philharmonic, who could pick any orchestra in the world to pair with.

But they wanted something that WASO had that they didn’t have at that time, because they had just been released from being a government orchestra, and the government pays the bills. But they’re no longer part of the broadcast and dictated to what they had to play. So WASO has been through the same thing, they used to be part of the ABC, they were given their schedules by programmers, they couldn’t really choose their own programs. And so you had that. You also had the fact that they also had to make the money when they were given work, whereas before broadcaster, just keep talking it up, they never saw the bills. So I thought that was a really interesting sort of thing to happen.

Of course, it never really happened once we got in there. I didn’t approach the orchestra, the orchestra approached me directly. Because they knew of the China thing. And because somebody said ‘I should have a chat to him (Alan), because he’d understand the China thing’. And if you want to be doing the concerts in China, you’d be able to get in. So I met with Craig (Whitehead – WASO Chief Executive) and we had a long lunch, which was a long, dry lunch, because he was going back to a concert. So, we didn’t get carried away. We just went through every bit of detail.

By the end of the lunch, I wanted to just film his passion, because I knew it’s going to hit a wall. I said to him, ‘you’ve got all these things, you’re bringing together all the money, you’re going to have to try and get all the things you’re bringing together an amazing project. And if you get that up, it’s going to be earth shattering, because so seldom does anybody get to bring that together. But you’re gonna hit some brick walls, and when you hit those brick walls, they’re gonna have to be big part of the story.’

And he said, ‘I want them to be a big part of the story’. So, he didn’t go in with his eyes shut.

Andrew: I think that is really important, especially of the past couple of years with COVID, the realities of the arts in Australia has been exposed like no other. And I know that people in the arts have continually talked about the need for more funding, the need for more support, but it’s been really exposed over the past two years as how much really needs to happen here. And yet, the story which takes place years ago, feels as relevant as it does now. And there’s an interesting point, which I think comes near the close of the film, where there’s this talk about the conversation of elite sports people versus the conversation of elite artists (where elite sports people are celebrated and lauded more than elite artists are). I’m really grateful that’s there because I think that’s an essential thing that a lot of people neglect when it comes to talking about art. And how did that resonate for you when you were hearing that being talked about?

Alan: It’s absolutely true. Doing the sort of work as long as I have… there’s been a recession at the point that we were opening up in Melbourne. We had contracts with two broadcasters for two substantial series and 30 days later was the crash and both broadcasters were insolvent. I could probably produce a dozen occasions where everything gets turned upside down.

You’re always going to have to get through those but the pandemic itself has been so broad, where you normally fill in your gaps, you can’t go. I was going to be the Australian producer for two that could turn into five slate of American films that were low-budget films they wanted to shoot out here, we got permission for them to go into Cocos (Keeling Islands) where the first one was going to be shot but then the Los Angeles office and the stars and all the rest of it started to get cold feet. They could come in, the government allowed them to bring the people in but their agents who are going ‘you may not get home’ and ‘we have more money for other shows for you’; the producer and director was a star himself and he convinced the stars to come because it was all at mid-price rate and the agents were going ‘well we’re not going to risk that those guys can’t come back’.

And that just blew the deals. There was two pictures gone.

And then we had work with China (that) just ceased, a big infrastructure project where we would design this global cinema for a company that wanted to do a huge project and was nearing its end… well it’s still sitting there unfinished because all the labor is diverted to building hospitals. So, all those things happen.

And then we had two movies being released, and no cinemas. What was The Naked Wanderer, now called Crazy About You and it’s being released on all the streamers the end of this month in the US, UK, Canada, Ireland and several other territories. It’s already gone out in Korea and Russia and all those sorts of places but it’s sat for 18 months not having any theaters to go in before Saban stepped up and bought it so it could go on streaming. You put all those together we’ve basically had to live off our existing income for research & development and basic business. There hasn’t been any income of any size because nothing has been made.

We were going to show this (Harmony) in the concert hall and the very week it was going to go into the concert hall was the week that the last shutdown happened (in Perth) and then after that everything was backed up and we wouldn’t have been able to get back into the concert hall until next year. So we that’s why we Jonathan (the distributor) and I chose to put it in the theater.

Andrew: I think it’s a great film. I always like seeing Perth on screen. Seeing your hometown on screen is lovely but there was something that brought a new perspective to the complexity of the Perth art scene that I was surprised by. From my perspective, I write about film, and I do interviews with people like yourself, but I’m not in the actual industry itself making things happen. I’m on the outside looking in. But getting to see how different things work in regard to the Perth Arts Festival, and how WASO works, and their relationships… it’s very complex.

Alan: It’s extremely complex. You have a finite amount of money that comes from the four year plans that the Government has, which gives them four years of certainty. But for an orchestra four years is not long. The fact they’ve got Asher Fisch is extraordinary because he’s done the Met, he’s a conductor for the Berlin Philharmonic. He’s got all sorts of these really permanent gigs that he goes to. He had three days in China, and then flew to New York to do two weeks at the Met.

He’s got that, but he loves coming out here because, he says it in the film, it’s his orchestra. Here he can come out and actually influence what happens. When he goes to something like the Met, they tell him what he’s going to do. It’s such a unique position, and yet the orchestra is really starting to get an international exposure now. They had one tour in 90 years outside of the country. And that tour was for mining companies, executives, traveling around China with the orchestra. That was years ago when it was the ABC. So, this was the first time they’ve gone offshore in their own right, in 90 years.

Andrew: It’s kind of crazy, that isn’t it? We know how good they are, because we get to see them. I’ve seen them multiple times, and I’ve just been in awe every single time. Whether it’s presenting a live film score or a symphony like this, it’s overwhelming how brilliant it is. And it feels like the rest of the world should know how great they are, too. And hopefully this does a bit of an effort in showing that.

Alan: Again, it’s about theaters. It hasn’t been released at all other than (this weekend). It’s being released by a UK distribution company, and they have enough faith in it (that) they want to hold it, which is good, because most of them have just given up and put them up straight to TV. Which is good that they have faith in it that they want to hold it (for theatres). But it also means nobody has seen it yet!

I’ve sold it to some territories where they didn’t really want to have to pay translations. They want to put it in cinemas, and that’s great, it’s where it should. A film like this we’ll never make cent out, it just doesn’t happen. It costs a million dollars to make, you spend all this time to put it all together. It’s got a 5.5 soundtrack, which is a huge amount of work on it, it took a long time to cut. Kevin Manning is the editor, he and I worked on five projects now over 25 years. He’s always my pick. But he’s busy.

Andrew: Isn’t that the case, when they’re really good, they get busy.

Alan: He’s also a muso. And he plays bass guitar and string bass. And he’s got a great sense of rhythm which we had to have for the tempos and things, but also, he and I can talk in shorthand and when you’ve got that much footage, we just talked scenes not necessarily cuts. I was there for 90% of the cut and we would work through three or four weeks’ worth of stuff and then we’d go ‘no, we haven’t done justice to the music’ or ‘we focus too much on that’, so you start working back and working back. And often in those circumstances if you’re working with an editor works purely visually, – Kevin is very good at working visually, he’s also a cameraman – if you work with somebody (who) doesn’t think story all the time it’s very easy to get sidetracked by visuals and music itself. We had to work out what the story was at any one time with the music to make the visuals add to the drama of it.

Andrew: The visuals are really beautiful too, seeing inside those auditoriums in China is just magnificent.

Alan: It’s a beautiful place. I had an arrangement on an apartment just up the road from the concert hall, but I’d never been in because the concert hall was only 18 months old, two years old. And I’d always be working at night. And when I went in, had a look at it, when we started up before the orchestra came in. And nobody stopped me walking into the theatre, so I was walking around the theatre, looking about and what not, and then somebody asked me to move a box, and so I did. *laughing*.

That stage, it sinks into the floor, you’ve set the orchestra up and it rises up from the floor. It’s acoustically very similar to the concert hall. And it just has everything. And because of what they play, it’s never full. They don’t compromise, they could easily put popular stuff in there, but they are really using that building in the school to push the classics (they have one to two and a half thousand music students). In China, you have half a million students at any one time going for piano exams.

Andrew: That’s kind of nice to hear that there is a dedication in that push for the arts too. It’s part of why I do what I do, in writing about films and championing films, where I try and elevate it to make Australian public realise that we make a lot of great films, we make a lot of great art here. And we need to respect that before it’s gone.

Alan: We need to take risks. We’re becoming extremely risk averse.

Andrew: We are. Look at the reaction to Nitram, that is a very risky film. And yet, it’s something that the audiences and the funding bodies have certainly said, ‘no, we don’t want to have much to do with that’. How do you deal with that as a filmmaker?

Alan: It’s really, really hard. It’s never been harder. It used to be that there was a sort of a cowboy period, I suppose, from the 1970s, through to the mid-80s, where risk was vital, if they didn’t want to do it. If they didn’t take a risk on it, they weren’t being bold in terms of broadcasters and what have you. But costs were lower, costs were a lot lower. And, even with inflation rates, costs were lower, because production teams were smaller, so they were less expensive. And if you couldn’t do something, or if it didn’t work, you weren’t out of the game, whereas now, the stakes are really high. And you keep seeing the same thing made over and over and over and over again.

Andrew: There is safety to that. There is a comfort to having something that is proven to work. And I guess, that’s one of the difficulties (for modern productions). It is very refreshing to hear high (level) figures in (Harmony) talking about the need for funding for the arts. I felt that there was a really pointed moment that I felt was very funny and very timely, where Janet Holmes à Court says ‘maybe we should swap funding of the submarines for the arts’.

*both laughing*

Alan: That’s a piece of gold and she said that in 2019. So, the submarines thing was a bit of an issue there. But what I really love is you get this ‘tinky’ sound which sound mixers wanted to take out, but I said ‘leave it in’. That’s her pearl bracelet tinking. Pearls the size of golf balls on it, complaining that there’s not enough money.

Andrew: A bit of self-reflection needed there maybe.

Alan: Oh no, she puts a huge amount into the arts.

The way that if a government’s talking billions, nobody questions it. Except maybe the opposition party will question it. If they talk in 100 million or more, nobody questions it, it’s obviously of great importance. Anything below that really doesn’t pass the pub test. It’s become a sport to spend big and to have big projects and so there’s going to be lots of jobs all that sort of stuff.

But there has to be a culture, you need to have some depth.

I was in London years ago, staying with a friend from London, who was staying with someone who designed cities. She said to me, ‘you must find it really difficult in Australia without having access to culture’. Well, I lived in Melbourne between two enormous museums. And she said, ‘oh, I know Melbourne well, you also have the MCG’. You certainly couldn’t say that here.

Andrew: Well, no. And that’s a difficult thing, isn’t it? Perth, I think is needing to find itself culturally. And I know that it’s been a conversation that’s been happening a lot lately about what kind of cultural things can we have established here. There’s lots of talk about a film studio. But it needs to be stuff that people can go and attend, art galleries; the new museum is fantastic as well, but there needs to be more.

Alan: But it’s always about building. That’s what they understand: buildings.

Because when you walk down the street you say ‘the so-and-so government built that’. It’s (about) sustaining what’s in the buildings. You’ve had the theater built in Northbridge (Heath Ledger Theatre), and not having anywhere near what it should have in it because nobody can afford to put stuff in it. You’ve got that rooftop garden on the art gallery now and you say ‘we’re gonna go and have a drink on the rooftop’, but you can’t see any new works.

Not in the permanent collection anyhow. And you have this kind of absurdity down here. I’m 10k away from Bunbury, and the Art Gallery here has a whole pile of collections out the back, because they don’t really have the resources to show them but they’ve been given them. They’ve got some amazing artworks and a whole lot of contemporary painters who have now gone to do big things elsewhere. And if you look at somewhere like Bendigo, the art gallery there, which has just been a huge success. Changed the city. They have a train that goes up on every opening, and it’s full of people going up from Melbourne, a special train. And they do great stuff in between bringing in shows from overseas. But that’s not going to happen in the regions. And it should be.

Andrew: Obviously, Cinefest Oz is great for Busselton, but what about the other 11 months of the year where Cinefest Oz isn’t on there? It would be nice to have a destination of something like that down there where we can go and see things. Earlier in the year I interviewed Bruce Beresford, and he has a documentary that he’d made recently (An Improbable Collection), that’s about a whole bunch of artworks from artists who have passed now, but their artworks predominantly lived in a small town in rural Victoria. It’s crazy.

Alan: There’s two sides to that. There’s collectors who don’t really want to show anybody it. There’s somebody in Melbourne who collects opera costumes. This is extraordinary warehouse full of opera costumes, but you’re not allowed to say where it is. Because it’s a hobby. Eventually, it’ll get bequeathed to somewhere and hopefully someone gets to put them up, because it goes right back to the 1900s. And they’ve been beautifully preserved. And the second is about money.

Andrew: Exactly. I think that’s the thing for me, I loathe to call what I do a hobby because it is a passion of mine to be able to sit here and write about Australian films and interview filmmakers like yourself, but I don’t get paid for it. And so therefore, on paper, it’s technically considered a hobby. And I feel that there are a lot of filmmakers, artists, musicians who are in the same kind of spot, they would love to call it a profession, they would love to call it something more than that, but the money just isn’t there. And breaking that barrier is hard. It’s very, very hard.

Alan: We’ve lost the apprenticeship system, and we had formal apprenticeships. But it’s not the same thing, having a few interns on a film, because they’re always way down the line. You’re not getting them above the line. And it’s above the line where the filmmakers have got to come from who keep the industry going, because nobody says we’re going to fund this film, because there’s a terrific PA. It’s got to be people exposed to seeing and understanding the complexities of having responsibility for a lot of money and having responsibility for having a vision that you get up on screen, whether you’re right or wrong yet keep the vision. And everybody wants to distract you from the vision.

You submit something to a screen agency and the screen agency decide they want to put it up for development or for production, and that goes before a board which consists of accountants and other bits and pieces, and somebody says no. And you never get to talk to them. You never know what they said. But it doesn’t get through, or somebody else is preferred because they’re ‘safe’, or the other one is because they have a name, and they know that it’ll get sold later on. So you’re then losing out to the people who should have a chance. It’s very, very difficult.

I don’t know if anybody’s getting it right, but probably there are parts of Canada who get it right more often than not, and that’s because it’s also part of their cultural attack on America. They want to be partly self-sufficient from America, but they don’t want their culture being buried all the time. But we don’t seem to see it that way.

Also, because it’s divided by states. You want to do something that shows off your state, which is terrific. But you can’t have filmmakers do only that. So by the very definition of doing that, and people are able to make enough to work, you’re driving them out of the state. They might come back every now and then do something but you’re driving them out.

Andrew: That’s the old adage is that you have great first-time feature filmmaker in Australia, and then they head over to America. Because that’s where the work is. And it’s a shame, it really is. I think that one of the things which Harmony does so well is that it shows how important it is to support the arts as a whole. And it shows clearly what is at stake and what can be lost. The journey itself is really powerful, but that notion of what we need to support, what we could lose is what sticks with me from this film. I think it’s really powerful.

Alan: Thank you, that’s what I was trying to do.

Andrew: There’s a lot to be proud of here, as I mentioned, I’ve watched a lot of music documentaries, and you kind of get into the rhythm of them. But this and Love in Bright Landscapes, which about the Triffids, they’re both surprised me, because they weren’t what I expected. They didn’t turn into what I expected. And that’s always a comfort. That’s always nice.

Andrew: That’s great. I really appreciate that. I mean, I’ve had to live with the film without having feedback for a long time.

Andrew: How do you do that?

Alan: It’s really, it’s really quite tough. Once we’ve finished the cut, and got it out there.

And then just nothing.

And then we got to a point, last year, we have to do something. There were things like there was a Mahler festival in Amsterdam, and that was going to be the original launch for the International (release). Because obviously it would go well with that. But Amsterdam was one of the first places to fall to COVID. So that didn’t happen. The planning went out the door, but in the meantime, I think its market is going to be streaming, which is great. Because I love watching those. It’s all about getting enough people to see it. But it’d be great if we could sit down with the politicians, do a Kubrick and pries their eyes open, make them watch it.

Andrew: I agree. I agree. There’s a lot of discussion about, and it’s valid discussion, I’m not trying to minimize it at all, but there’s a lot of discussion about infrastructure, building infrastructure, building roads, because it is a tangible thing. And it keeps people employed. I understand that. But we need more than that. Specifically talking about WA, if it’s going to become a place for people to visit once everything opens up and returns to some kind of normal, then we need to provide something that’s enticing people to come here. And a new road is not that attractive.

Alan: It’s like they’re building a bypass for Bunbury at the moment so people can get to the wine region quicker. And there’s a guy who’s an ex-copper up the road saying, ‘that actually means they’re going to be drinking an extra half an hour in the wineries. And we’ll be scraping more buddies off the road.’

Andrew: That’s really sad.

Alan: If you look at it in terms of the music here, building the concert hall, these guys don’t have anywhere to rehearse. They rehearse in the concert hall when it’s free, but they have to hire it out to keep it going. And when it’s not free, the rehearsals become pathetically few. It’s only really when Asher’s there that they get full chance to work like he would normally work. Because there’s no rehearsal rooms or individual rooms for the orchestra sections to work on things. They have to do it in their own time, or some of them work out of the cafeteria in the morning.

Andrew: Which is not a suitable rehearsal space at all.

Alan: They’ve just got some money for it, but that’s now seven years on from when they first were trying to do that. And of course, as you see in the film, the bottom is starting to fall down. I drove in to pick up my gear and this guy ran out and said ‘don’t park there, there are cracks!’ And that was the part where you see the jacks put up the next day.

Andrew: I remember going to a concert and seeing that and I decided to then Park across the road because I was like, well, who knows what might happen!

Alan: They’re gradually getting those bits and pieces, but so much of their energy has to go towards it. Not actually the performances and things.

Andrew: I once again want to applaud you for this film. I’m really keen to see what people say about it and how they appreciate it too, because I think that this is a film for audiences who are not just interested in Symphony Orchestra music to seek out. It’s really important stuff.