It’s been a little over a year since I first talked to Sue Maslin AO about documentary filmmaking and took a look back at some of the great feature films and documentaries that she has helped bring to life. In the year since, the world of documentary films in Australia has exploded in an impressive fashion. In that first discussion, Sue talked about executive producing Anonymous Club, Danny Cohen’s excellent documentary about musician Courtney Barnett, alongside Alec Morgan and Tom Zubrycki’s magnificent film about William T. Onus, Ablaze, and the Catherine Dwyer’s excellent Brazen Hussies about the Australian Women’s Liberation Movement in the 1960s. These are just two of the documentaries released into cinemas during 2022 out a total of 81 Australian feature and documentary films.

Sue took part in a panel at the 2023 Australian International Documentary Conference (AIDC) alongside producer Tait Brady (Love in Bright Landscapes), Paul Wiegard (co-founder and CEO of Madman Entertainment), producer Charlotte Wilson (Greenhouse by Joost), and programmer Sasha Close (Gold Coast Film Festival & Brisbane International Film Festival), moderated by producer Chris Kamen (Franklin) on March 8th, where the discussion around the future of screening documentary filmmaking in cinemas was explored.

In early 2022, Perth was swinging in and out of COVID lockdown status, with Melbourne and Sydney in the hangover period of spending months on end in lockdown. Cinemas and filmmakers were struggling, and even though audiences were hesitant to see films with an audience, they did crave filmmaking. In conversation with Sue prior to the conference, I asked her about what changes the industry had seen since our discussion and what she gleaned from the boom of Australian feature films.

“Incredibly there were 81 Australian feature films released by distributors into our market in 2022. 81! This is just unheard of. [We traditionally had] 25 to 35 a year, [and then] we were getting up to about 55 a year. All of those releases are released by distributors. There are independent one-offs, [and] if you count those, there’s another 40 or so on top of that. [Of those] 81 releases, 37 were documentary films. Which means there are a lot of documentary films being made.

“The vast bulk are not performing particularly well. In fact, the vast bulk of Australian feature films are not performing at the moment. But if you look at the [20] top performing [Australian films] of 2022, 10 of those were documentaries.”

Sue graciously provided the box office numbers from both Numero and the Comscore list for this interview, both of which provide a fascinating look into the reception of Australian films at the box office. We know that films like Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis and the third Wog Boy film were well received by audiences, but it was interesting to see how widely received Australian documentaries were by audiences. In the list of new Australian films released during 2022, the following ten films featured heavily in the top 20:

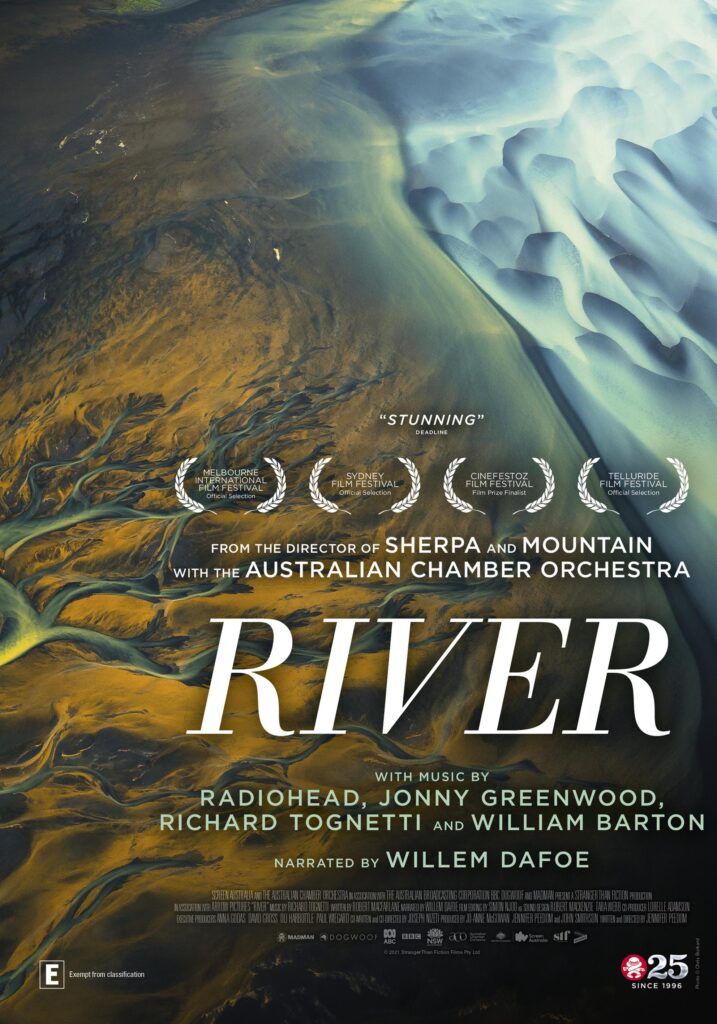

The Lost City of Melbourne (Gus Berger), Franklin (Kasimir Burgess), Facing Monsters (Bentley Dean), This Much I Know to Be True (Andrew Dominik), River (Jennifer Peedom), Embrace: Kids (Taryn Brumfitt OAM), Blind Ambition (Robert Coe, Warwick Ross), Everybody’s Oma (Jason van Genderen), and Love in Bright Landscapes (Jonathan Alley).

As Sue explained, “documentary films are contributing significantly to the annual box office for Australian films. There is no doubt about that. However, around half of all the documentary films earn $10,000 or less at the box office. These films are not even recovering their own P&A or marketing costs, so we have to ask, ‘are these films really theatrical?’

“Despite the reality of what’s happening to Australian cinema at the moment, despite the reality of what’s happening post-COVID, by and large, audiences have moved online, even more so than ever before. It’s very, very hard to get audiences back into cinemas for independent films full stop. The box office for these films is down even further compared with non-Hollywood studio films.”

As I’ve been writing the Australian Film Book series, I’ve been discovering that there are more and more feature films being produced than ever before. The output is reaching peak levels, and yet the audiences simply aren’t turning out for these films, no matter how great the quality is. From an industry perspective, Sue wondered about this too, “we’re finding it harder to get our Australian films seen by local audiences, we’ve now [also] got this exponential growth in filmmakers wanting to make feature films and get them into the cinema.” It’s a subject that Sue wanted to pose to the panellists at the AIDC, “why is it so important to make a feature doc? Where are they destined [for]? Are the films actually cinematic? Are they actually theatrical? If you run through the list, the films that perform best are the films that are the most cinematic.”

One of Australia’s most cinematic documentarians is Jennifer Peedom, the director behind acclaimed work like Sherpa, Mountain, and her 2022 film, River. Sue moderated a panel with Jennifer, Emma Madison (Screenrights), and Rufus Richardson (DocPlay) called The Long and the Short of Monetising Documentary Rights. Sue commented about Jennifer’s work, “Jen has been very successful in creating an experience that sits around in the theatre. When Mountain came out, it made more than $2 million pre-COVID. River came out in 2022, and so far it’s made $200,000, a 10th of what Mountain made.”

Part of the impressive cinema release for Mountain included presentations of the film with the Australian Chamber Orchestra, alongside a premiere at the Sydney Opera House. This immersive theatrical experience made the cinema viewing more than just watching a film in a theatre, it became an event.

As Sue mentions about River, which is due to receive the same kind of immersive experience, “it hasn’t yet had its run as the experiential event. Once [Jennifer] has that run, it’ll boost the box office up further. She has tapped into something that I’ve been saying for a long time: the film alone is not enough. You have to create the experience, the event, the social media, the impact. Everything that sits around the film, that becomes what the offering is.”

It’s something that Sue wants more filmmakers to think about when they consider a theatrical run for their films. Namely, how do you make the act of going out to the cinema more than just watching a film? How do you get audience members to experience and engage with non-Hollywood filmmaking in a manner that they may otherwise have not done before? After all, Australian filmmakers make some damn great films, and audiences are aware of that, but the manner that they’ve become attuned to the new normal of streaming everything, and treating cinemas like they’re only for Marvel or James Cameron films is one that needs to be broken.

One such release that helped buck the trend was Jonathan Alley’s Love in Bright Landscapes, which toured Australia with a Triffids tribute band playing the bands notable releases at each of the cinema events. As Sue mentioned, “[Tait Brady sold] the tickets for $50 a head, and he’s [made] a successful release.” Just like Jennifer Peedom did with the Australian Chamber Orchestra and her films, tying a documentary to the subject matter and the artists involved with the film helps make the screening more of an event, which is something that Sue herself had personal experience with as Danny Cohen’s Anonymous Club launched in 2022.

“I distributed Anonymous Club, a beautiful film [about Courtney Barnett], all shot on 16mm. [It’s an] incredible, theatrical, emotional space that goes into a very intimate, emotional journey. It ticks all the boxes of what in my view should be cinematic and theatrical. Yet, it didn’t perform in the cinema. That’s not to say that it’s not going to perform over the long term.”

It’s seems that even though I personally saw Anonymous Club multiple times in the cinema (it was my most watched film of 2022, after all), that wasn’t enough to boost its box office presence in Australia. Overall, Anonymous Club ended up as the 34th placed Australian film at the box office, next to How to Thrive and Under Cover, both of which had specialised screenings.

Sue continues, “Courtney’s got legions of fans, millions of followers worldwide. She has a very active social media base. Her youth audience will sell out [a concert] wherever she plays, they are there for the experience. Whenever we had screenings with Courtney present, [they] sold out, no worries. The minute that you start to screen the film as a standalone film, then you drop back [to] how most Australian films were performing; that is, the audience is not there. They all know about it, but they’re not turning up. This is not just documentaries. This is right across the board.

“That leads you to say, ‘well, there’s other rationales.’ People are making lots of feature docs, many of which hope to have a theatrical release. But of course, there’s festival releases. Theatrical docs do have a very active life here in Australia, and of course, worldwide, it’s just that there are more film festival opportunities for documentary films. I think audiences are realising that if they want to see really good documentaries, that’s where they find them. They find them in curated programmes at film festivals. It amazes me that the documentary sessions are often the first to sell out at film festivals everywhere. People know that’s a destination.”

With that notion in mind, it is important to note that many of the documentaries that I’ve covered here at The Curb have come from festival releases first, and then a theatrical release second. In many ways, the festival release is the awareness campaign for documentary films. If they sell out at festivals, then the theatrical run is almost like gravy.

In Australia, many of the documentaries that are produced here are also delivered on free to air channels like the ABC and SBS, or on their own streaming platforms in reduced versions. Additionally, those that don’t end up on ABC or SBS may end up on Madman’s documentary focused streaming service, DocPlay. Sue talks about that online life for documentary films, “the reality is that most documentaries will probably end up either on television, on streamers, or in a cut down version used by community groups. Community groups don’t tend to want to use a feature length doc because they want to have a discussion at the end of the screening. So if you’ve got a 100 minute doc, and then you’ve got another hour or so of discussions, [that’s] a really big event. They tend to want to watch a shorter, one-hour version, which is why we usually make two versions [of a documentary].

Ultimately though, the same question to documentarians applies:

“What is the rationale for your story to actually be targeted into a theatrical space?”

From a media perspective, I hear the stories of filmmakers pushing hard to get their films into cinemas. These are often creations that have taken years, sometimes decades, to bring to life. People put a lot of blood, sweat, tears, and personal funding into bringing these films to life. Naturally, as filmmakers, they crave that cinema experience. I posed the question to Sue about how filmmakers need to approach that personal discussion within themselves about where is the best place for their film:

“It’s a creative decision, but it’s also a business decision. The two have to get together. We’re not writing novels here. We’re making mass media for audiences delivered over screens. Yes, it’s a creative decision, but at all times, I can’t see the point in making any work unless at the same time you’re thinking about who it is that you’re wanting to talk to [in] the audience. They have to go hand in hand.”

Sue continues, “Part of the problem is that there’s too much desire to tell the story in the absence of really thinking about where that story will ultimately sit and who will ultimately see it. Because once you think about it, you have to ask yourself really tough questions. Why will [the audience] want to see that film? Why [are they] going to pay good, hard-earned money, when they can stay home and watch Netflix and all the other myriad of streamers for a fraction of the cost. They know perfectly well because they’ve had two years of the COVID experience, that you can get a multitude of quality documentaries online. Why are you going to pay good money to go and see documentaries in a cinema now?

“Unless you can answer that question, I don’t think that the creative impulse is enough to drive forward a documentary project anymore.”

Now, I know that many readers may get upset or frustrated by reading that reasoning, and to be fair, I can understand that sentiment completely. After all, whether it’s the eagerness of getting to work on a Monday morning to tell your colleagues at work about the great weekend you’ve just had, or the burning desire to write the next Ducks, Newburyport and turn the literary form on its head, the burning desire to tell a story sits within us all.

But the reality is, in todays mass market where the ability to turn that creative drive to turn an idea into reality by picking up a camera, or even just using your phone, has made filmmaking almost too easy. Yes, there’s a freedom in being able to create just about anything, but there’s also the need and push to have a creative force within yourself that can be met by knowing that there might be an audience on the other side who is eager to watch your film.

When I started writing the first Australian Film Book, my partner asked me who the target audience was for the book. I starred blankly at her, and somewhat foolishly gave her the response, “me.” Now, that is very well true. I personally want to read books about Australian films, just like many Australian filmmakers, whether they be documentarians or genre filmmakers or beyond, want to see the story that they’re making on screen. But that burning desire to see or hear or read our own stories must come with a clear answer of who the target audience is for what is being produced. It took me a while to work out who the audience for my books would be, but as soon as I found it, the audience was there, in turn making the Kickstarter campaign a success.

I mentioned to Sue just how immense the quantity of Australian films being produced right now are, and how we’ve got more filmmakers than ever producing films. I commented about how wonderful it is to see a fruitful, eager industry at work, both from a screen body funded aspect, as well as from an independent aspect. But as both Sue and I discussed, the audiences simply aren’t turning up to see Australian films.

Yet, something else has changed since I last spoke to Sue, and that’s the reality that we have a new Federal government, and with a new government, we have the returning Minister for the Arts, Tony Burke. After a rapid tour of Australia in 2022, Tony Burke jumped on the front foot and pulled together an arts policy that sought to rectify a decade of stagnation in the industry with the Australian arts scene. The result was:

Revive: Australia’s Cultural Policy for the next five years.

A place for every story, a story for every place.

It’s an aspirational piece of work, full of hope, vision, and pure intentions. It’s something that I’ve read through a few times, and each time I’ve tried to pull back my cynical gaze just a little bit more. That word, ‘hope’, is a dangerous thing sometimes. It sparks a fire to creativity, but at the same time, that fire can be doused and smothered for an age.

Yet, there is a clear vision in ‘Revive’, one that encompasses all aspects of the Australian arts. To be clear, this isn’t an arts policy that is simply focused on filmmaking, naturally that would be awfully narrow-minded. It embraces theatre, dance, art, writing, and so much more.

It’s a policy that’s split into five pillars:

- Pillar 1 – First Nations First

- Pillar 2 – A Place for Every Story

- Pillar 3 – Centrality of the Artist

- Pillar 4 – Strong Cultural Infrastructure

- Pillar 5 – Engaging the Audience

If we focus on that final pillar, the one that is most pertinent to this discussion of reaching audiences, it exposes one of the emerging issues with the arts policy as a whole: a lack of focus around the theatrical experience. There is welcome discussion of streaming quotas for Australian content, which makes a wealth of sense given that that is where the dominant audience share sits, but by not mentioning the need to grow, support, and maintain the cinematic experience suggests that there is no further growth that can be attained here.

While the purpose of this interview came because of the 2023 AIDC, it’s worthwhile noting that Sue has also participated in fruitful, exciting, and actionable discussions at the Australian Feature Film Summit in 2021 and 2022.

Commenting on the new arts policy, Sue remarks, “this is something that is obviously a much bigger question, [and] is something with the Australian Feature Film Summit that we’ve attempted to address, and will continue to address by bringing together all sectors of the industry, the exhibitors, the distributors, the filmmakers, and the agencies all together in one space to drive this forward. It’s a very real issue that is being driven by industry, which is should be.

“Of course, having a cultural policy now gives us some additional leverage. We’ve seen what happens when you do proactive campaigns to celebrate Australian cinema. We saw it [with the] Summer of Cinema [campaign] at the beginning of 2021. In the middle of the pandemic, the phenomenal box office result for Australian films where people took a punt because Hollywood [films were] absent, they had to see an Australian film, but they liked them, and the figures were really substantial. Every film experienced an incredible bump in box office as a result of that. We had this opportunity where people had lost the habit of going to the movies, or don’t routinely see Australian films, were coming out and they were liking what they saw.”

Once the pandemic restrictions were lifted around the world, it once again became harder for Australian films to compete at the box office simply because of the sheer market domination and presence that these films with marketing budgets and the ability to weather weeks in cinemas had against smaller Aussie films which often lack a marketing budget, or can only be booked into smaller arthouse cinemas. This isn’t to say that Australian films in 2022 weren’t successful, they just didn’t hit the same levels as they did in 2021.

Sue talked about some of the films that stood out in the Australian film scene, and highlighted one of the reasons why that may be: “There’s just as many interesting Australian films in the 2022 bunch. We’ve got everything from blockbusters like Elvis, through to films that targeted a more female demographic like How to Please a Woman, The Drover’s Wife, Falling for Figaro, and Seriously Red. All of those female driven projects that are all sitting up in the top 10. But, the box office figures are nowhere near as robust as they could be.

“So the question is, how do we get people back into the habit again?

“I think having a cultural policy means that there’s the potential for whole of industry campaigns. We’ve got to really look at having more data about audience behaviour, and that’s happening as well. A high priority for us at the summit [was] to get data research into audience behaviour done, but more importantly, shared with filmmakers, which is something that has not happened in the past. That’s sort of bubbling away in the background as well.”

The word ‘data’ gets thrown around a bunch, but it’s important to note that a lot of the data that is collected is gathered to improve industries or the fields that the data is being collected for. I am personally someone who previously worked in a data collection field, and have had first-hand experience of seeing how the data that was gathered was used to improve services for people in the community, and when used effectively and appropriately, it’s a powerful and brilliant thing.

Sue continues, talking about the importance of connecting filmmakers with that audience data, which in turn would allow filmmakers to answer that vital question of who their audience is: “And then to have ground-up funding opportunities to put filmmakers together with the exhibitors who are closest to the audience and having the opportunity to test their ideas. We’ve been separated for too long. We’ve got to get filmmakers at the coalface talking to exhibitors, finding out what audience behaviour is, what is going to get them in.

“We know some things work extremely well, like anything that is event based [and] anything that involves talent. [It] doesn’t have to always be music docs, it can be other experiences. This is, of course, something that is the cornerstone of impact strategies [for] social impact films where they’re supported by campaigns. There’s a lot of ways to engage audiences rather than just simply saying ‘look, our film is out on this week, here’s the poster, here’s the trailer, here’s a review, come and see my film.’ It’s got to be much, much more sophisticated than that going forward.”

A social impact campaign is often something that’s applied to social impact films, like Franklin or How to Thrive. These are documentaries that give the audience an actionable purpose once the screening has finished, making the film just one part of a much larger piece of the pie.

A small case study that I can personally present is the impact that Damon Gameau’s 2040 has had on my local suburb. The film was released in 2019, with an awareness campaign across social media that preceded the nation-wide in person Q&A tour with Damon and fellow climate activists in person. I interviewed Damon in person in an electric vehicle, making it one of the more unique locations that I’ve interviewed a filmmaker, and he talked about the importance of those in person connections at the time. It’s that connection that spurred someone in my suburb to pick up the 2040 book, which became a weathered tome as they read through it frequently with their family, picking up ideas and tips on how to create a localised climate action strategy in their suburb.

The energy and excitement that they had that came from watching the film, meeting Damon, buying the book, re-reading the book and rewatching the film, kicked that family into action during lockdown here in Perth, and in turn, the family created a local activism group to help combat climate change on the streets of our suburb. They embraced the ‘think global, act local’ approach, and now a couple of years on, that once small Facebook group has now spawned other groups that are pushing to create suburban tree canopies and save large trees in our suburbs.

The notable thing about this small case study is that it’s one typically applies only to documentary films, where the campaign before and after its release helps maintain the longevity of the film. I asked Sue about whether the same kind of social impact campaign for a film like 2040 could be applied to music documentaries like Love in Bright Landscapes or Anonymous Club, which gave way to an answer about her own personal experience with creating a social impact campaign for one of the biggest Australian films ever:

“The 360 degrees methodology of conveying ideas and themes and engagement with audience [can]. We’ve got a lot to learn from social impact campaigns. Fortunately, I’ve worked across both documentaries and feature films for years. It was that sort of documentary experience, in some ways, that idea of a 360 approach to engage an audience that drove how we wanted to present The Dressmaker. Yes, everybody will say, you hit the ball way out of the park, [but] nobody expected it to do as well, me included, as it did.

“I can tell you, that campaign did not start with Universal Pictures when they had the final film and the trailer, and then the release; that was not the beginning of the campaign. The beginning of the campaign started two years prior to the film going into production. When we did put together our social media strategy, we started building our fan base. We invited the fan base to audition to be extras in the film, which of course meant the socials went gangbusters because everybody wanted to be in a film with Kate [Winslet] and Liam [Hemsworth].

“It then continued through the making of the film to the strategy of creating an event and experience: ‘grab your girlfriends, grab a glass of champagne, get dressed up and come to The Dressmaker.’ That was the experience. It wasn’t ‘buy a ticket and come see the movie.’ It meant groups of women did exactly that. And they shared dressing up and all of that stuff. That happened through the release. And then after, it continued through [when] Marion Boyce, the costume designer, and I put together the exhibition of the dresses.”

In 2019, the NFSA hosted a stunning exhibition that featured the costumes of The Dressmaker with backdrops that referenced locations from the film. I visited the exhibition when I was in Canberra that year, and honestly, I’m still absolutely stunned by the intricacy and brilliance of the costumes in person. These are works of art, and getting to experience them in person, some four years after the film first arrived on Australian screens, transported me back to Dungatar.

Sue continues, “so you’re thinking about it in a long arc. You build excitement [and] you build awareness not by making the film. I get this so many times from filmmakers, particularly emerging filmmakers, who ring up and say, ‘I’ve just finished my first feature film, what do I do now? Where do I go? What do I do with this now?’ And you go, ‘that is such a great question, but you should have asked it two years ago or a year ago before you started making the film.’ Because the ‘what do I do now’ should be completely answered for you. Only half the job is done when you’ve made the film. The other 50% is connecting with the audience.”

I commented that there is a notion that sometimes filmmakers are almost scared to connect with an audience, because it’s that final validation about whether the film that they’ve spent years of their lives making is any good or not. These are often works of pure dedication, weekends spent away from families, or pushing to get that idea out of their mind and realised on film. It’s something that filmmaker Gus Berger knows all too well, having spent much of the Melbourne lockdown period creating his expansive and historical documentary The Lost City of Melbourne. It’s a film that Sue uses as a great example of reaching an audience:

“[Looking] at the top performing documentaries, [there’s] The Lost City of Melbourne. I take my hat off to Gus Berger for doing this. Who, in any other state, is going to go and see this movie? Yet, he’s topped the list for documentary films in 2022. And that film is still screening! I saw it last weekend on a Sunday afternoon in Gus’ cinema, which is a 52-seater. It was almost full, it’s incredible.

“It’s an archival film. [Gus] knows its audience, [and has] got a clever sort of strategy. It’s kind of like the platform releases that we used to have in the old days where you build awareness of a film and keep it on and keep it running. If it’s a quality film, which it is, then give the people the opportunity to see it over time. And people are seeing it. It was released on the first of September, and there’s still 40 people in a cinema last Sunday afternoon seeing it. I find that extraordinary. I love it.

“Then there’s music films [like] Lee Kernaghan: Boy from the Bush, Love in Bright Landscapes, and also with This Much I Know to Be True. Music is part of the element of getting audiences in. Then there’s the campaign films: Franklin, Greenhouse by Yoast, Embrace: Kids, Blind Ambition. These films are all supported by a really strong campaign. And then going down the list a bit further, you’ve got more music: The Angels: Kickin’ Down the Door, Wash My Soul in the River’s Flow, Anonymous Club. There are clues in here about what are bringing in audiences to the cinema.

“In all of this, you’d have to say that the production sector in theatrical documentary is very, very vibrant. The best performing films are the ones that have the long tail. That is yes, they can have a theatrical release, but they go to find their audience on streamers, potentially on television, potentially in educational areas, and that is a perfectly valid strategy for making a feature doc. We’ve been doing it here at Film Art Media for years, and managing the rights over the long tail has been the key to our sustainability.”

It’s worthwhile pointing out the bold words that are on the Film Art Media website:

Stories that engage.

Ideas that matter.

These are important values for filmmakers to keep in the back of their mind as they make a film. It’s clear that for Sue Maslin AO, these are ideas and values that reinforce how she engages with producing, promoting, and discussing films.

That discussion is a vital point when it comes to sustaining the longevity of films beyond their initial screenings, and it’s a point that Sue touches on when it comes to media coverage, “if you make a feature documentary, and it goes straight to TV or streaming, you’re not going to get the editorial coverage that you get if you make a film that then goes on to cinemas. The editorial coverage is so important because unlike just the TV review and ‘what’s on tonight’ and the micro-reference that you might get in a programme guide, the editorial really addresses why we make documentaries; which is because we’re trying to convey ideas to audiences, and there are important themes and subjects that we really, really want the Australian public to be aware of. While they may not get to see the film, they’ll certainly get to read it on The Conversation or on their online news feeds or social media.

“Theatrical drives all of that.”

I should personally take a cheeky moment to highlight that you can also read about it on The Curb or Cinema Australia. I agree completely with Sue’s point, noting that theatrical releases do often get greater media coverage because there is a PR push to get people into theatres. I want to also highlight that the ability for filmmakers themselves to contact publications like The Conversation, The Curb, Screenhub, IF.com.au, Metro, or Cinema Australia is always there. They aren’t solely reliant on the PR department of a streaming service to try and connect filmmakers with media.

Sue continues, “the work that you guys do is just so fundamental, because we can’t afford the publicity, we don’t have money for publicity campaigns. Every editorial piece gives us phenomenal value across media that we don’t have to actually pay for. It’s more than that; yes, it’s promoting the film, which we love, and we really desperately need, but it’s about the ideas. Getting people to seriously engage with ideas is really hard these days in our mainstream press.

“If you look at, for instance, the pages around reviews of books, they engage with ideas, they engage with the subject matter, with what the writer was setting out to do. There’s a deep discussion, often controversy, but it’s all about the idea. Go to the film review pages, and it’s about, who’s in it, what they wore at the premiere, what they ate while the interviewer was talking to them. It’s just so facile. It’s very hard to get ideas. With a few notable exceptions, we don’t really have a film criticism culture in Australia anymore.”

This point is particularly salient for me and my fellow Australian film critics. We are just as vital in championing, supporting, amplifying and valuing the work of Australian filmmakers. I know there are passionate supporters of Australian films, ones that manage the criticism (both negative and positive) of the Aussie film output with grace and style. But there used to be more of us, and it’s something that Sue has noticed change in the critical field over the years.

“I’m old enough to have been around making films in the early 1980s and have been the beneficiary of all of the work that the filmmakers in the filmmaker co-ops did in the 1970s. They weren’t just making film. They were building film criticism, they were building film magazines. We had Cinema Papers, there was Filmnews, there was a myriad of different avenues and everybody wanted to engage with the culture of a brand new Australian film industry or reborn Australian film industry for the second time. It wasn’t just about making films.”

That communal discussion and celebration of the work of Australian filmmakers is one that I’m personally seeing being driven less from Australian filmmaking communities. Naturally, this statement comes with exceptions, with filmmakers like Heath Davis championing as loud as he can every new Australian film released each week via his personal Facebook page, or local industry events like the WA Made Film Festival and Perth’s Revelation Film Festival, where filmmakers from all over the state and the nation commune to champion each other and support each other’s work.

Yet, there’s something that struck a chord with me that Sue said that is all too familiar with what I’m personally seeing in the discussion of Australian films nowadays:

“The sad thing I find in a lot of emerging filmmakers these days is the first question I asked them as well. ‘What’s the latest Australian film you’ve been to see?’ They haven’t seen any Australian films! And they’re not necessarily really particularly interested in that kind of culture that underpins our production culture.”

I mentioned to Sue that one of the questions I ask Australian filmmakers is about what being an Australian filmmaker means to them. The question is one that has created confusion, excitement, intrigue, and deep introspection. It’s one that many filmmakers don’t truly consider, and I wonder if it’s because of the dominance of American culture in Australia. It was something that my parents feared when I was a kid, banning my sister and I from watching The Simpsons (although I do wonder if that was mostly because they couldn’t stand Marge’s voice), namely the manner that American culture overwhelms so many other nations cultures. We’re attuned to seeing and hearing American faces and voices on screen, telling American stories, to the point that Australian filmmakers are losing what it means to be an Australian filmmaker.

This is not to say that every Australian filmmaker needs to be telling Australian stories, but there’s something pointed about hearing and seeing Australian actors and stories on screen. It’s validates us, it highlights our presence in the global cultural sphere. It shows that we matter and we’re important.

In wrapping up my chat with Sue, she made a final point which sits at the core of this whole discussion: getting bums in seats at movie theatres.

“The other comment I want to make is that the cinemas themselves, exhibitors, are up for it. Even though they make most of their money out of the studio pictures, they’re already made campaigns, they put them up and they pretty much run themselves. It’s actually the Australian films that gives them their job satisfaction. The joy of seeing audiences come in, line up at the box office, and buy tickets to see a good Aussie movie [excites them]. They’re desperate for more, they want them, they love working with us. I think that opportunity is there, and we just have to have a different conversation around it.”

And that’s a conversation which I know I’ll personally be excited to continue having with filmmakers, colleagues, friends and family. There’s something truly exciting about talking about Australian films, and from a purely personal level, I get a great joy when I’m able to discuss Australian cinema at length with filmmakers like Sue, like Danny Cohen, like Jonathan Alley, like Gus Berger, and so many more. There’s an excitement that’s there in their voice as they tell their story and share their journey to getting it made in the world.

But as Sue says, that journey needs to start earlier. It needs to start years before the cameras even start capturing that first, important shot on location. You’re excited about making your film, include people in that excitement earlier, because the sooner you do, the sooner you build an audience who will be along with you for the ride for years.

This interview has been edited for clarity purposes.