Vonne Patiag is unstoppable.

His 2018 short film Tomgirl about Filipino queer identity played film festivals around the world, was shortlisted in the Sundance Screenwriters Lab, got him into the Inside Out Film Festival Finance Forum, and most recently earned him a prestigious spot in the Toronto International Film Festival Filmmakers Lab. In 2019, he created the ABC web-series Halal Gurls, the first hijabi sitcom, which he also co-produced and entirely edited. Last year, The Unusual Suspects aired on SBS, a miniseries starring Miranda Otto, Aina Dumlao, Michelle Vergara Moore, and Lena Cruz, which placed the lives of three Filipino women on Australian screens in another first. Vonne was initially hired as a Filipino consultant and freelance writer on the project, was promoted to co-writer of the whole show, and then co-producer. Oh yes, and he also managed to do a good deal of theatre in cast and solo productions.

Nisha-Anne caught up with this busy, busy creative in October 2021 to talk about writing for the upcoming anthology film Here Out West, which opened Sydney Film Festival to sold out sessions and has been nominated for an AWGIE. We talked for so long about the trajectory of his fascinating career that this interview will be published in two sections.

In this first part, Vonne discusses the creative and community collaboration of Tomgirl and developing it into a feature, the producer’s role in developing and mandating inclusive cultural practices in the Australian screen industry, getting away from the trauma paradigm in queer narratives, and the ever looming demon of imposter syndrome. We also discussed the genesis and intricacies of filming Halal Gurls, what he learnt onset Operation Buffalo, and his experiences on The Unusual Suspects as far more than the token diversity hire.

Here Out West will be available in cinemas February 3 and will air on ABC later this year.

So a month ago you did the TIFF Filmmakers Lab?

Yes!

How was that?

That was incredible. Life-changing really for me. For a few reasons but I think it’s like – I’ll frame it this way. Twenty directors chosen from across the world and TIFF went for two weeks and the lab went for, I think, six to eight days. So I hilariously sleep-trained for it. Like I completely changed my body clock to be on Toronto time even though I didn’t leave my office here [in Sydney]. So the first session we had with our industry liaison, the TIFF industry manager – she says, “Hi everyone, I’m just going to get this out of the way. You twenty are the best up and coming directors of your generation, you’re all deserving to be here. And I’m saying this because we don’t have time for imposter syndrome.” She’s like, “We need to hit the ground running with this program. We have a jam-packed program for you guys.” This was our introduction. I just want to get this out of the way, “Introduce yourselves but you’re all deserving to be here, you’re all incredibly special, and your projects are fucking kick-ass.”

That to me – it’s so weird to say but it almost broke me because it’s like you never really hear that in the local industry. Do you know what I mean? Like in Australia. I was just like, “Oh my god, I’ve spent so long fighting to earn a place.” And to be told that you are so talented and special and super deserving on an international scale, it really brought to life some of the issues with navigating a career in Australia. It’s something that’s never really changed but we often talk about the fact that when you get to that mid-level place in your career, a lot of practitioners leave Australia. And I think I really understand why now. Because the tall poppy stuff is really real.

And I will say that there was another Australian director, Jess Barclay Lawton who was in that with me, she’s in Melbourne. The whole lab was incredible. You know, to have mentors and governors who were – like we had Miranda Harcourt who is Nicole Kidman’s acting coach as one of our governors. And Ramin Bahrani who was the director of The White Tiger (2021) on Netflix. Having all these really big mentors and guest speakers – the two that really stand out for me are Edgar Wright – he was one of our guest speakers – and then Leslye Headland who’s the showrunner of Russian Doll on Netflix.

I thought I was going into this lab thinking it’ll be like a financing model. But it was literally about craftmanship and creativity and psychology, and [they] really beat it into us, “Look, you are the director, you are sitting on top of your project, and everything is about your relationship to yourself.” It was really fulfilling to hear from really seasoned professionals who are also people of colour and how they navigate identity politics and really understanding that the conversation in Australia is very different to the international conversation.

I don’t want to speak out of turn for Jess, the other director, but we would both go into these group sessions, kind of realising how institutionalised as filmmakers we are in Australia. We were like “Oh my god, there’s other ways to do things? This is crazy!” And really feeling – I call it creative freedom – like it erased all our psychological blocks and I was like, “Oh my god, we can do anything! This is crazy! Like why are we not being taught this, to instill this confidence in us?”

Obviously the conversations around diversity are so important and are so important to me, but I guess, as someone who just likes to work, I’m also wary of when we talk too much and don’t do enough work. So to be in this lab with twenty directors from across the world who are all just like, “Put it in the work, dude. Just let the work speak for itself.”

Towards the end, it was kind of embarrassing honestly to be Australian because I would continually be like, “I’m so sorry I keep talking about this stuff, like I know it’s such an Australian problem.” I think being in an international market showed what some of our local problems are. And for me, it’s recognising where I’m putting my energy now, in a really productive way. I’ve always wanted to have an international component to my career so I think leaning more into that and being [focused on] what’s serving an international market rather than getting frustrated with what’s happening here.

All of us were already pretty seasoned. So it was just incredible to hear, you know, to hear Edgar Wright be so generous and vulnerable with his experience. I never write alone because it terrifies me, and just to hear – I absolutely love Hot Fuzz (2007) and Shaun Of The Dead (2004) – and to hear the vulnerability under that really made everything so human and [it made me] understand the power of vulnerability and authenticity but not in an exploitative sense, more in a storytelling sense. And I think that when you’re a POC, you kind of misconstrue that message a bit, like I’m just going to put my trauma onscreen and it’s super unsafe for me to do that. Whereas now I have a bit of a mature understanding about my craft.

About the problems in [the Australian industry], do you mean in terms of the attitudes or in terms of processes in terms of grants and stuff like that? Or both?

I think in terms of the infrastructure, a lot of the times I felt in the past that I had been developing projects, it’s almost like you have to write personal essays about your life and your life experience and the themes of the film. And I always find that when I go to America, people are like “What’s the story?” I’m like, “Oh okay, well, you know, I’m from Western Sydney and it’s like the Brooklyn of Australia” and people just sit there like [looking bored], “Oh okay, and what’s the story?” Having the mentality of the power of stories but also storytelling first is something that we’re not properly cultivating here. There’s a lot of side-stepping and so many conversations – I’m always happy that conversations happen but I think productive outcomes are really important, especially to give people actual experience. I’m always really wary when there’s a lot of people talking and they don’t have any experience to share.

In light of all you’ve just said, I love the fact that you’ve carved your own path, you’ve made your own opportunities. And that’s amazing, Vonne.

The thing with that is I’m Filipino and I’m Asian and I have this feeling that I look really young. (laughs)

We [Asians] all do, right?

Yeah, I know, right? And I’ve been working at my career for twelve years and it really saddens me when people discount that experience. I didn’t make my first funded short film until 2016, do you know what I mean? Like I was self-funding my stuff, I was in the trenches. And that time isn’t publicised. Okay, so I’ve worked on some features and tv shows now and that’s heavily publicised and all of a sudden, it looks like I’ve popped up overnight.

But you’ve been putting in the hard work all that time. Let’s talk about Tomgirl [the feature in the making]. So you attended a workshop at the Inside Out Film Festival on financing queer films?

It was incredible because in May, Inside Out which is one of the biggest queer LGBT+ film festivals in the world based in Toronto. They have a market component called the Film Finance Forum and it’s the fifth year it’s ever been held and it’s meant to be the bastion of the queer film market alongside Frameline in San Francisco. Yeah, the applications opened and obviously it was digital, second year they did it digitally. It’s really interesting because it’s Canadian-based and they were only taking [films that were] based in UK, Canada, US, or Australia because they’re cornering a market. But, you know, there were films from Spain and there was a lot of diversity.

But basically [it was] this outreach for queer films that were heading into production or in advanced development. And yeah, I’m proud to say we were the only Australian film to be selected for this year. Only eight films were chosen. So it was such a beautiful cohort to be part of, and that was an absolutely incredible experience. And again, a lot of that international validation really meant something. Because we were one of the only projects to only have a script. A lot of the other projects were heading into production or at very advanced development, had their exec producers. I think one of them had Stephen Fry attached as executive producer. And here we were, this little scrappy team, just me and my producing partner and literally a second draft script.

That was really beautiful, to be told that the strength of the script was enough to get into this. It set us up with two weeks of crazy market meetings non-stop. We met with distributors and sales agents from across the world, UK, France, Germany, Canada, New York. We met with agents and other production companies looking to co-produce. So yeah, it was really beautiful as a soft introduction to the market because now we have a few partners that we’re calling on.

I think with Tomgirl, where the feature is at now, we’re heading into another draft so we’re solidifying a lot of the feedback we’ve gotten. But it’s all a matter of now if we partner with that distribution company in Montreal, she really wanted this and she can sell it this way so let’s do it for that. And because I’m wearing different hats [as writer/director/producer], I am a really big believer in developing your own voice for the market. So it’s kind of keeping that tension of this is what I want to say as an artist, but also what is my audience going to experience [and] also what does the market want? Because I think that’s the most viable way to get projects up, selling things that people want. (laughs)

You got admitted on the basis of the [Tomgirl] script but you did have your proof of concept video, I mean your short film?

Oh yes. We had the short film as well that we submitted as well. And that’s been a very powerful piece of work because I think to see obviously a script in action and the design elements and all the flourishes that I put in really sells the vision of it. I always try and write my scripts in such a visual way that it kind of matches but nothing beats actually seeing in action.

So how did Tomgirl the short come about?

That was funded in 2017 by CreateNSW and SBS so it was the GEFF initiative, Generator: Emerging Filmmakers Fund. And that was funded for the fortieth anniversary of Mardi Gras so I guess you’d call it an initiative fund where they funded six films and would broadcast them as part of the Mardi Gras celebrations so we were one of the films chosen for that.

You’ve written some pieces about the bakla tradition and about Filipino presentation of gender and queerness. And I know that this story was based on you meeting your older cousin Norman when you were eight. At what point did you decide you wanted to make this into a film or something?

You know, it’s really funny because I can pinpoint this to the exact moment. So to bring it back down to the first film I was funded for, [which] was a film called Window in 2016 that was funded by St Kilda Film Festival. That was a film about me, essentially. And I worked with my producing partner, Maren Smith, and I moved back to Sydney in 2017 and we were successful in getting some Screen [Australia] funding for development of a tv show and we were looking for more opportunities. And the GEFF initiative came up and I think we were just really well suited. Obviously it looked for LGBT practitioners to spearhead their projects. So I was like really keen to put my hat in the ring and had some ideas, and Maren in her beautiful way – she’s a really inclusive producer. She’s like, “Is there a story that you want to tell? What’s something – you know, not pushing you at all but is there something that you’re burning to say?” And I was like, “I don’t know. I really don’t know what to do or what I’m doing.”

So I caught a flight to Melbourne to see my friends because I missed it so much. And I remember being on the phone with her, I called her and I was like, “Okay, look, I will think about it on the plane. I have no idea, I have no freaking idea what to do.” And I was on this flight and, you know, it’s a very short flight. So I was writing some stuff down and I had this one idea, I was like “Why did I move back to Sydney? I love Melbourne so much. Why did I move back to Sydney? This is ridiculous.” And the one thought I had was well, I really wanted to be with my parents because I’m getting a bit older, they’re getting a bit older. I haven’t lived at home for a while so I was like I’ll reconnect with my parents. And I just had this one thought, it was one of those guttural thoughts that really strike through everything and it was “Ugh, I really hate being Filipino.” It was this demonic voice from my belly, just being like “Ugh. Filipino. God!”

I totally relate. Yeah.

As soon as I said that, I was like “Oh my god, the next film’s going to be Filipino.” (laughs) I just knew, I just knew. This is something really important, there’s this impulse. And I called Maren straight away and I wrote – I literally spent ten minutes writing the story of Tomgirl on a napkin. It was “boy, uncle who’s bakla, wants to dress as a girl.” Because I got all these images of – look, me and my brother are 90s kids, latchkey kids, very bored in the suburbs. And we would dress up all the time and do crazy stuff. And there was no judgement when it’s just and your sibling. So I was like, “I used to put towels on my head all the time and I would play Mary in the manger.” (laughs) You know? And it’s in retrospect that you think these things are important.

Yeah, so I just wrote the idea down and I called Maren straight away as soon as I landed and was like, “Oh my god, I have this idea. Filipino, bakla tradition, a boy who wants to cross-dress as a girl.” And she just was like, “Oh my god, write it down.” Yeah, that’s literally how that idea came about. And no joke, we pitched it two weeks later.

To CreateNSW?

Yeah, it was two weeks to put a pitch together. That’s an example for me of – I’m always someone who likes to create from not just my life but like listening to that impulse, that bodily impulse. I think it’s so important. And all the other times I’ve let my head run things, “Oh this film would be really good for like – I’m going to do it this way,” it’s never worked out. It’s always been like my literal belly will tell me, “Oh my god, this is it, yes, go for that.” I feel like most of the opportunities I’ve had actually have come from that intuition so.

So I watched Tomgirl the short and I absolutely loved it, oh my gosh. It was just fucken flawless, man.

(laughs)

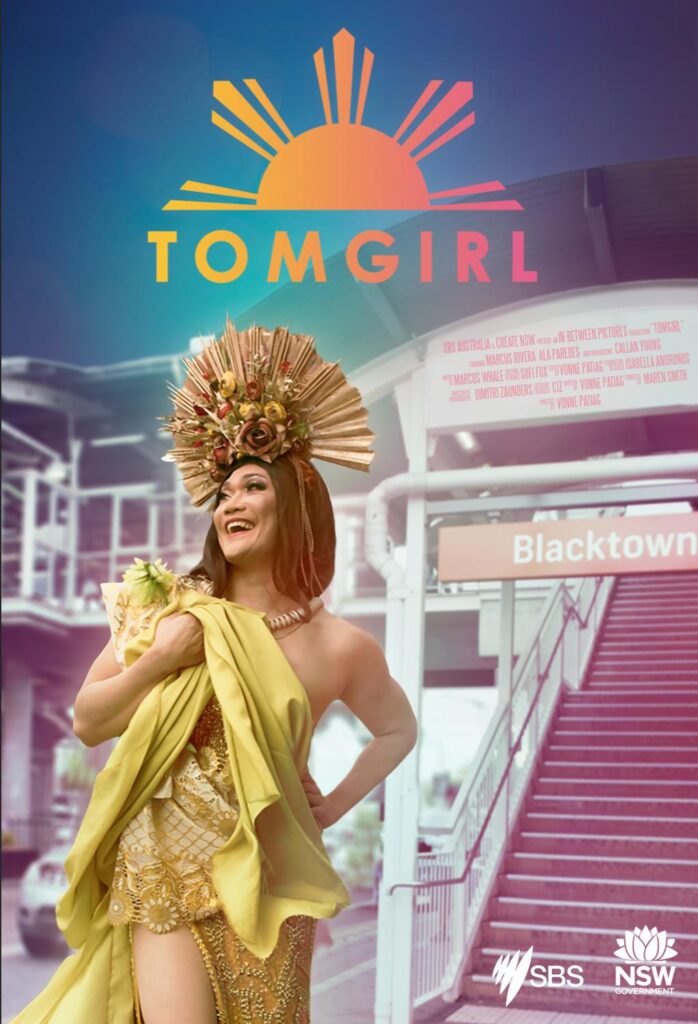

[At this point, Vonne reached to the side and picked up a full-sized framed poster of Tomgirl and held it up for me to see.]

Oh! Beautiful! Love it!

(laughs) I have too many posters now but.

Well, that’s got to go up, man. And I love that poster as well and I want to talk about the design elements like you said. The colours and the sense of sunshine in that film was so beautiful and like a hyperreal version of Western Sydney. I live in the inner west but, you know, I travel everywhere, especially for food.

Yep!

Yeah. (laughs)

(laughs)

I immediately recognised that sense of Australian sunshine and the sense of Sydney sunshine with the colours and everything. But I was really impressed with the tone of Tomgirl because I kept bracing myself for something horrible to happen. And you very deliberately did not go down that way. You ended on that really empowering note. At what point did you realise that that’s what you wanted to do?

You know, even though I’m Filipino, I think the film is definitely about me reconnecting with my Filipino roots. I worked on the script with my mother and worked with her on the translations and really got inside her head. And it was really beautiful because I think sometimes – there’s not a language barrier but there’s a generational barrier between like our generation and our parents where they don’t want to talk about a lot of the trauma that they went through back in the motherland.

Actually working on a creative piece together gave licence to open up so many conversations with my parents, especially my mum. She’d be like, “Oh my god, yes, I remember this time” and I was getting so much from her. I think there’s a safety in storytelling. And I really took that onboard because other than that, there was a really huge research component with – I worked a lot with Blacktown Arts Centre on it to infuse the film with a really local sensibility to Blacktown as well. I’ve lived in Blacktown my whole life, I grew up here, but I just really want to tap into the spirit of the area and the spirit of the Filipino people in this area in a way that – obviously working from intuition is really important but when you get to craftsmanship, you do need communication, you do need collaboration. To enact creativity, you need to be able to communicate what you need.

So I really wanted to work with, you know, Paschal Berry who is a senior arts leader in the Filipino community here. I wanted to work with him, I wanted to work with Caroline Garcia and talk to a prominent Filipino artist, and speak to Bhenji Ra who is a beautiful trans vogue mother, and Justin Shoulder. All these other Filipino artists and practitioners who are working in a very sensitive intercultural space with Filipino culture and commodity, to see how they were enabling this intercultural conversation, too.

I really wanted this film to feel really Filipino, like really Filipino. So what better way to do that than let the community teach you? There was this really beautiful community exchange between myself and my own community, and I really started to understand my parents, especially their generation of moving here. It’s something that’s really changed my perspective on Filipino culture but we’re very repressed. (laughs) And this is sort of the uncomfortable stuff that people don’t often talk about but there’s a lot of trauma [with] being a migrant, moving to another country. You’re cut off from a village-type support network, you’re just by yourself, you’re very individualistic, just with your partner which, you know – sometimes even those marriages are out of convenience or like you’re used to having other people interject and suddenly it’s you and your partner.

Everything gets amplified.

Yeah, everything gets amplified when it’s just you. And it brought me back to my childhood and I was thinking, you know what, my parents infused my childhood with so much joy. Even though as an adult, I understood that there was so much trauma and so much anxiety about building a future in this country. But the joy kept coming through. And my mum said this really beautiful thing – my mum is like a hilarious woman of idioms where sometimes she’ll read things on Facebook and share them with me, and they are the most profound statements you will ever hear. But to her, she doesn’t understand the power of those words, you know what I mean? She’ll be like, “Oh I read this thing, I think you might like it,” and she’ll share it and I’m just like, “Oh my god.”

With this film, she [said], “To be Filipino, you must get through the pain to get to the joy.” She was like, “There is no other way around it. That’s why we laugh so much and that’s why we’re so joyous as people, because we really get through that pain to earn that happiness.” And that explains everything about my family and my childhood and everything.

So with Tomgirl, it was interesting working with executives from SBS and CreateNSW because you get notes, you get notes from everywhere. And it was really beautiful to write the script and infuse it with this cultural sensibility because I think by making it so local and so authentic, it almost became untouchable, like the structure. And yes, you know, we would get notes like, “Hey, is there a third act sort of climax thing?” And I would dive back in and be like, “Okay, but for me, the climax of the film is actually the personal recognition and the acceptance that you can’t do this all the time.” Like that beautiful scene in the moonlight, right?

Yep.

And I didn’t mind going back in and sort of explaining why this was important, not just from a personal lens but also from a cultural lens and that realisation [that] yes, it might appear a bit smaller in terms of action but I think it’s paramount in terms of personality.

Absolutely. And it’s a funny thing to say, that third act climax, because to me it was so obvious, that scene with him putting on the wig and walking through those kids and the kids, you know, falling back. I mean, there’s your fricken climax, what more do you need?

(laughs) Yeah. I think that was a really special moment for me, learning sometimes that – and it’s not an antagonistic thing.

No.

It’s not us versus them in terms of cultural consideration. I think it’s beautiful to be localised and super authentic and very unique. And if you can find that uniqueness in a story that you’re telling, then you also know what to defend. And that really gave me a lot of confidence in, yeah, like you said, telling the story the way I wanted. And you are right. It’s been funny because a lot of people – I think Australia – again, it is some of that institution stuff but sometimes when we look at LGBT representation, we automatically pop a trauma dark storyline under it. And I was like, “I don’t know. If you’re the queer character or if you’re a child as in Tomgirl, you’re not really looking for that trauma.” And I think that’s what really saved me. You know what, the two main characters in this are Justin and Uncle Norman, and Uncle Norman has built up this resilience to handle this stuff and find the joy in the everyday, and Justin’s learning from an innocent and naïve beautiful place. And the two of these perspectives combined mean that I can deliver a celebration of my community and a celebration of my culture rather than a – I don’t know.

A trauma thing.

Yeah, you know, a racist tirade, a car runs through their house sort of climax. I don’t want to do that, I want to celebrate my community. And I always kept that in mind.

Having said that, all of that, I really was a little fearful for Justin for after the movie ended. I was like, “Oh my god, the kids run after him and they beat him up.”

Yeah, I’ve always been encouraged to expand Tomgirl into a longer feature because so many people just felt, like you just said, there’s so much more to the story. So that’s what I’ve been working on for the last two years, working on the script. It’s been interesting because as a feature, you go to some more tense places, you have to drive the audience towards extremes. So it’s been interesting to, I guess, tell that version of Tomgirl as well, where I am examining the extremes. Like, yes, like you said, what happens to Justin after that?

Can you talk a little about that development process? You said you’re in the second draft now. Is the short film going to be the first act or a little longer, the first two acts? What do you think?

Still deciding some of those things. I was shortlisted for the Sundance Screenwriters Lab with the Tomgirl script last year. So I actually wrote the first draft – I’ve been developing the idea for, I guess, the first half of last year, especially in lockdown. I did a residency this year to tackle the second draft just before the [Inside Out Film Finance Forum] and then obviously with [that] and TIFF, it just armed me with so much knowledge. We’re heading into a third development with an aim to really secure and lock down some market attachments.

In the last few years, there’s been some beautiful films that have really changed the landscape, like Minari (2020) is such a beautiful film, and it’s glorious to be able to call on a film as a reference point when you’re talking in some of these conversations. “It’s like Minari but set in the Nineties, not in the Eighties, and it’s a Filipino family.” People are just like “I understand.” You know? And the other reference I have, especially for Americans, is Little Miss Sunshine (2006). It’s a family coming together and really learning again what a family is. It’s been interesting to extrapolate and draw on some of the themes from the short film and really tease them out.

What always fascinated me was what happens after, like you said. I do think the short is maybe the first act or more of the first half. And I definitely want to honour the mother character as well, give her a lot of story, and again base it on a lot of untold stories of my own mother as well, really just rounding out that world. Yeah, right now I’m at a really fun place where I have too much story. (laughs) So much story, like so much where people are like, “Can this just be a four-part tv show, please? Because you have so much.”

Which it could! It could, Vonne!

Yeah, I know, I know! I’ve had a few meetings where people suggest that. And I’m like “Maybe, actually. You know, maybe.” So I’m in the process of figuring out what’s the most effective sort of feature version of the film, and I think narrowing down what I want to say with it because right now I have a lot to say. But I think it’s important to really narrow the focus.

I really loved the mother relationship and how it was so tender, and also the relationship between the mother and the brother. I was really struck by the fact that there was no father or husband in the household, that it was a family of sister, brother, and son. It was interesting that you said you gravitated more towards the conversations with your mum rather than the conversations with your dad. Was your dad not really interested in that?

No, he is. He’s very quiet. (laughs)

Oh yes. Yes, I understand.

A very quiet man.

The quiet Asian man. Yes.

Yeah. It’s hilarious to the people who know me very well because all my films, all my projects are either super passionate, super loud, super fiery. Or super quiet, super tender. And I’m just like, “It’s my parents, man. It’s my parents in me.” But yeah, the masculinity question definitely is something I’m exploring in the feature.

That’s great. That’s what I was going towards, the masculinity part of the feature. It was interesting what you said about the four-part series because Tomgirl as a four-part series would follow on really well from The Unusual Suspects as a four-part series, right? Expanding the Filipino representation onscreen.

Yes. (laughs)

I hope it happens in some form or the other.

Thank you.

I wanted to ask about the design elements [of Tomgirl] because I loved what you did with the subtitles. Not just having the subtitles there in a specific colour but with the highlighting of certain words and not translating certain words and with the question marks. I was watching it, going “Why has he put question marks there? I mean, he knows what it means. Is it that he wants us to question what it means?” And then I watched The Unusual Suspects: Unwrapped and how you said how Tagalog is quite a hard language to lock down and I went, “That’s why it is, that’s why the question marks.”

It’s so hard, oh my god.

Why do you think that is?

I’ve been trying to get my parents to teach me Tagalog for years, and I don’t know how they learnt. It’s a language that needs to be experienced. I think it’s a language that requires full immersion because, you know, we slip into Taglish, like Tagalog and English. And it’s really common to start speaking in English halfway through a sentence. With growing up — it’s something that I’m kind of exploring in the feature more so but it was in the short – I remember being five and my parents switching to English to speak to me. It was this thing in the Nineties that they kept telling migrant people who came over, “Speak to your kids in English so you give them a better chance.” Me and my cousins – we’re the oldest generation of Filipinos who kind of have this really broken understanding. I have the listening skills to understand Tagalog fluently but I cannot speak a word back.

Same, same with me with Hindi.

And with the subtitles, I really wanted to honour that third culture experience of your own language where my mum will be speaking in Tagalog and I’ll be like (concentrating face) “What does that word mean?” And obviously I didn’t want to put that in because I didn’t want the kid to have to say it over and over again. Half the time I kind of extrapolate meaning from what my parents say without really understanding what it is. I think as a kid, you are prone to sort of create your meaning sometimes with language, even if it is English. And I really wanted to steer Justin’s storyline towards this – I call it mistranslation factor. And that’s kind of where we end up with Espy [the mother character] where she’s like, “I feel like Justin no longer hears it when I say ‘I love you.’”

I love that. Are you going to have that design element with the – because I noticed it was orange and yellow, wasn’t it?

Pink and yellow.

When did that decision for the colours and really integrating the subtitles come in?

I based the whole colour palette off the Filipino flag.

Wow.

Because on the Filipino flag, there’s a sun. It’s red, blue, white and yellow, the sun. Working with my cinematographer and designer, I really wanted every colour [to be] something on this flag. Each character is a colour of the flag. Like Esperanza wears a blue uniform. Norman’s bakla outfit is yellow and radiant. And then Justin’s heels are red.

And then we obviously have the queer perspective on that. So like these are our base colours, but how are we going to push this? So all of a sudden, the moonlight is super blue. And the red is pushed to a point where it’s pink. I think just having those conversations, again it came down to the idea of infusing the film with a really strong Filipino sensibility. It allowed those choices and so [when we] do the poster, have this gradient that goes from blue to red. Because Norman is the yellow on it on that poster. And it just informed everything.

And now that you’ve said about the sun, now I realise the logo [above the title] is the half-sun!

Yes!

I love that! I love that shit, that is my shit!

(laughs)

Every time I watch a film, I’m like “Ooh, look at the colour there, ooh look at the red there.” It’s so rewarding.

Yeah, everything’s intentional, that’s what I say. I’m that sort of filmmaker who doesn’t like ragging on other films, I don’t like criticising other directors because every director does the best they can with what they have. But also, everything’s intentional that you’re seeing. So absorb it all. This is how the story is told by this person.

I was reading your opinion piece in The Guardian about gender and how Tomgirl was part of the bakla tradition and how Filipino tradition has that idea of another gender. And I love that you mentioned hijras from India as well because that’s what I grew up with, seeing them. We were terrified of them, it’s the repercussions of colonialism in India whereas before in ancient Hindu society, apparently they were fully integrated into society, but then they become this figure of terror and fear. In terms of that drawing upon our Asian heritage that goes back so much further beyond colonialism which has fucked up our ideas of gender and sexuality, is that something that you want to pursue in the feature film? Is it possible that they might go back to the Philippines? What do you think?

If my producer were here, she’d just [be like] stop encouraging this.

(laughs)

(laughs) But from the first draft, there is an extended sequence where there is a Philippines trip. Because the feature has become about home, like building a sense of home, how to build a sense of home in Australia. And I think in order to do that, you need to compare what home kind of looks like before. Because one of the sentiments my parents have always shared is when they go back to the Philippines, it doesn’t feel like home anymore. You know? So I just really want to strike that chord.

But in terms of the gender expression question – I mean, Tomgirl is an extension of me so, you know, I’m a bit hard to define as well. I’m proud of that. So when we sort of made the film and was releasing the film, I think that’s why the Guardian article was so empowering for me, to get on the forefront of this, and that was coupled with my talk at All About Women [festival in Sydney] as well. Shoutout to Edwina Throsby for curating me to go on that panel because I was literally one of only two men speaking at a panel about women. Yeah, I really took that honour [seriously].

For me, Tomgirl and Filipino queer identity kind of skates between the letters, LGBTQIA+. And I think when you’re looking at intersectional ideas of identity and sexuality, they do kind of sift through the spaces in between. And that’s also why my company is called In-Between Pictures.

Yeah, I armed myself with a lot of research and a lot of knowledge, especially accounts of first contact of Spanish missionaries who would encounter the traditional bakla people who were the village elders. Because in Philippines, back in the village Indigenous times, it was actually regarded to be closer to god because you were more man than man, and more woman than woman. You actually transcend everything. Which is why in Philippines, typically bakla performers are very popular. They are the highest paid comedians and most famous Filipinos we have.

But you know, when you take that paradigm that exists in Philippines and translate it to – there’s a lot of accounts from like San Francisco in the Sixties and Seventies where a lot of bakla people would go over and then all of a sudden the way we start talking about bakla, like that Tagalog word gets mistranslated to be “gay”. And that’s an example of cultural identities that get lost in migration and lost in translation.

It’s this generation of queer people who are moving to these Western countries and being told, “Oh no, you’re gay. You’re not – this is just gay.” And to be accepted by a local queer community, you kind of have to morph yourself. And I think at that time, I was still in this very introspective period where I was looking internally at what I identified as. And I was like — I don’t really – like I have friends who identify as gay, and I didn’t feel that spiritual connection to them as well. I just don’t think that’s super how I want to define myself because I don’t see that for me. There’s this, again, intuitive body feeling where I’m just like, “It’s just not me, I don’t know what it is.”

And when I started learning about these cultural identities where in Philippines, Tagalog isn’t a gendered language. It doesn’t discriminate in terms of language in terms of male and female. It almost feels like a blob, like you’re just people. And that spoke more to me. The very Western English definitions we put on identity are actually very limiting for a lot of intercultural conversations so I don’t partake in those now.

I totally agree with that intuitive feeling. And I feel like now okay, we’ve reclaimed the word “queer” since the Eighties and maybe that’s a better fit. I mean, that’s the word I’m more comfortable with because I feel the same way – like I don’t know if I’m male, I don’t know if I’m female, and sometimes I’m a fucken swirl of cosmic colour trapped in a body.

Yeah! I mean, I just say I’m queer as well. And not to discount other people’s perspectives.

No. But you’re just trying to find the right thing for you.

Whatever’s most comfortable.

Absolutely. I noticed that you edited both Tomgirl and Halal Gurls. I love the fact that you really seem to take charge of your own narratives, like your creative narratives. Stop blushing, Vonne, I can see you! (laughs)

(laughs) Yeah, I do. I do.

Has that always been something important to you right from the beginning?

You know, I think if I were younger, I would say it was out of necessity. You know how it’s sometimes “Oh, I just produce out of necessity” or “I direct, edit out of necessity.” I am a trained editor. It was my first professional job to be paid for in film. Obviously, I always wanted to be director, writer, producer. But no one’s going to pay you to do that when you’re twenty. I was editing full-time for five years and doing agency work and learning how to copy-write and produce and direct and shoot. It’s been one of the most empowering experiences of learning the practical uses of craft, you know? To work for an agency. I think it’s really important. Hopefully, a lot more people take that on that opportunity.

Especially Tomgirl, because of the language component – again, I learnt the script to the point where I couldn’t say the Tagalog but I obviously can hear it and understand what it is. And that was one of the inclusive parts of production choices where – because the actors who played Norman and Espy are fluent in Tagalog. Sometimes they would do – especially in rehearsals, they would say the lines in a way that is the exact same meaning in English but completely different in Tagalog. Tagalog is a language that’s alive, and you have to have someone who can clue in and be like “I think that’s different to this take but like that word is a slightly different nuance.” So it was a decision very early on for me to edit Tomgirl because of that reason.

And with Halal Gurls?

Yeah, with Halal Gurls, I guess that was a bit of a different situation because we were – how do I say this – very time-pressured. (laughs) You know, we shot that whole show in nine days, maybe ten days. And delivered it two months later. And we’d sent offers out to editors and we were working with a few, we were talking to them. And my producing partner on that, Petra Lovrencic – I remember we had this meeting and she was like, “Okay, I’m just going to call it.” She [said] “I really like your editing, I really like Tomgirl, the way you edited that. I think you should edit it. Because you’re going to be so much faster.” And I was like, “Yeah. I know.” (laughs) I’m just a very fast editor. It’s like the director in me can speak to the editor in me, and make those decisions. Yeah, so I ended up editing the whole show.

It gives a great cohesion to everything, the pace, the voice.

And it was important to know that – again, to always know these decisions upfront. So this was a thing that we set in place before our rehearsals, before our readthrough. As a director going into production, I really wanted Halal Gurls to be very fast-paced, kind of like that Tina Fey 30 Rock like bang-bang-bang, no breaks, no breaks, no breaks. And what was really fun is the actors were so game and really brought the energy. And then all of a sudden when I signed on as editor, I was like “Okay, I can maybe add that pace in editing.” Like we might not need to go as fast as I originally intended because now, let’s add another shot and let’s make it quick-cutting. And I think that worked better to get the pace across.

Because that was again an inclusive decision because we were working with a lot of non-actors. So I felt like sending everyone episodes of 30 Rock and [saying] “This is our pace,” it can scare people. So I [felt] like as a director and as a producer, I want to support the talent that we have, and this is a really good middle ground, this is a really strong way to get my intention across without having to call on training and experiences that maybe these actors don’t have. I’m a big believer in supporting talent to deliver the job.

That segues perfectly to my next question but I’m going to interrupt that and ask you: who are your favourite editors?

Thelma Schoonmaker, definitely. And then, you know, I’m going to be a bit controversial and say I’m a really big fan of Xavier Dolan.

Why is that controversial?

You know, that might be an Australian reaction. Because I find whenever I talk about directors who edit their own stuff, there’s always this kind of like this eye-roll, like “Oh my god, control freak.” And I actually think Xavier Dolan’s a very talented editor as well, and I love all his films that he’s edited. Because again he has such a distinct directorial pace with his dialogue and with his choreography that he understands in such a nuanced way. And I think part of me likes doing that for myself.

So I’ll go back to my original question before we got side-tracked on the editor thing. I really love the fact that aside from having your own fierce creative voice and having your own projects, you have this great thing where you alternate between your own projects and supporting other people’s creativity. I see that with Halal Gurls, I see that with The Unusual Suspects. Especially with Halal Gurls, I read about how you were working in the fashion house and you were having lunch with all these hijabi girls and you wanted to amplify their voices. Which I think is so great, especially for a young brown queer man — I’m just going to say it – right?

Yeah.

Because your voice has been so denied yourself, so the fact that you’re actually using what privilege you’ve got to amplify other people’s voices is so great. Was that something that was a conscious choice or just happened, the alternating between you and other people?

After I delivered Tomgirl, everyone really wanted me to do a feature. Right? Everyone really wanted me to do my tv show as well, because I had received already development funding for it. And what I did was I went into theatre. (laughs) And I wrote a lot of theatre, I did my first stage play called Obviously which was a queer sitcom which was really fun. And I like being challenged and I like every project to teach me something. I like that process of teaching but also being taught, like I love this reciprocity of growing with my creativity. And I’m telling you, everyone was like (claps) “Tomgirl feature, Tomgirl feature, come on, like straightaway.” And I was like, “Mmm, I don’t know. I’m just not – my body isn’t vibing with it.”

With Halal Gurls, my best friend ran Hijab House and we’re best friends for a very long time since high school, so I was always helping him. And I was in this state where I was writing a lot of theatre and I was getting into writers’ rooms and tv writing and going with the flow. You know, being like I’m just going to open myself up to the industry now and see what’s happening. So yeah, I’d gone to Melbourne to work on the fashion store that he opened up, I helped with the one in Greenacre. And I literally was a labourer, like I was building these shelves. And yeah, you know, I had been around my best friend for so long – he’s Lebanese – so yeah, we just grew up together and I know his sisters very well.

So we’ve always laughed about the fact that like all the hijabi women who worked with him were always super fierce and funny and hilarious and funny and the most strong empowered people you’ve ever met. But if you didn’t have that personal connection, if you didn’t have that sort of safety to have a personal conversation, they just appear visibly very subjugated. Which, you know, I really hated. Like I’ve always felt like these women are the funniest women in Australia. And there are all these narratives about how they’re victims or whatever. And this was something that was percolating for a long time. Like “Oh my god, they’re just so funny.” That’s what I kept saying, “They’re just so funny.” And I just remember that key image of seeing hijabi women like on their phones, snapchatting and drinking orange soda. And I got more to talking with my friend and I was like “You know what’s really fascinating like” –

Oh, this is something that’s never been published but I was talking to my friend about the Drake concert. Like Drake had come to Australia, to Sydney, and was doing a show. And I think [my friend and I] were going to see a movie and he was like, “I don’t know if I can go with you because I might have to take my sisters to go see Drake. Unless one of their older cousins takes them.” And it was this really intricate negotiation in the family of if three female cousins go together and one of them is a lot older, then that’s okay. But if not, [he has] to go with them.

It was inspiring to me that there’s a solution that navigates the middle ground tension between culture and faith and Australian identity. And the fact that they just skate the line in a hilarious way (laughs) and solve these problems that are so intrinsic to their identity that no one else is having but in a way that still upholds their faith, still upholds their familial traditions, still upholds what they want but there’s this solution that you never expect. And that was what really fascinated me about that world so.

I was lucky enough to be part of a producing crash course at ICE, Information Cultural Exchange at Parramatta, that I was doing. We had to pitch an idea to get into this course, right? And then in the last session because they were hilarious, they [said] “You have to now pitch a new idea completely, from scratch.” And I was like, “Oh shoot, okay sure.” I was at home, preparing to leave to go to this last session and I wrote this idea, like, “Err, I have nothing so three hijabi women living their best lives.” (laughs) “In Bankstown. Okay, and one of them is like mid-twenties, one of them is her sister, and one of them is an older cousin who is a chain-smoker.” I was pulling these ideas really quickly.

On the drive, I called my friend and [said], “What do you think about this idea of a comedy series with three hijabi women, etc? And I want to call it Yallah Girls because, you know, they always say—

Yeah, “yallah.”

So I was like yeah, Yallah Girls, I don’t know. And then my friend [said], “Um, it’s really good.” He’s like, “That’s really funny, but my only note – call it Halal Girls.”

(laughs)

Because it’s like topical. And I was like, “Oh that’s really funny.” And I was like, “You know what, and I’ll change the I to a U, make it a bit sassy.” (laughs)

(laughs) Love it. I started watching it and I sent it immediately to my hijabi cousin in Kuwait. She’s half-Persian, half-Indian.

(laughs)

When I was looking at the production credits, it was so collaborative.

Yeah, so basically what happened after that was the pitch did really well in that room and it didn’t win anything, but one of the producers who were listening in on the pitches came up to me afterwards, and he was like “Hey, I think this idea is gold.” He said, “I really think you’re sitting on something really good, it’s really funny.” And what I later learnt was that producer was Peter Herbert who is the senior lecturer at AFTRS for producing, and he is responsible for Acropolis Now.

Oh! I loved that show!

Yeah! Right? So he had kind of an inference in building Effie as this really powerful character. So we had this meeting afterwards and he was like, “You’re sitting on another Effie. I really think you have something going on here.” And that was it, and honestly that confidence again of somebody believing in the project meant I kept it burning away. And then from that point, I was like “Okay, how do I actually make this?” And I’m not here to criticise other production companies on how they want to do things. I just literally was like, “How do I want to make this?”

And I had a really fun time on Tomgirl collaborating with community and diving into a world that maybe I didn’t know and the amount of research required. I think levels of research can really help foster empathy and compassion and collaboration as well, like preparing yourself. I started going to Bankstown Poetry Slam, I started going to writers’ festivals, I started reading a lot, did a lot of research, and always had my best friend as a familial resource. But just started arming myself with what’s an actual story here, what’s actually happening?

Through that process, I engaged with a lot of theatre as well and started to flag that there was a really big lack of writers from the hijabi community who were working in film in general. And then the conversation is like an investigation: why is that? What about the infrastructure is holding out these creatives? Why is this film not a viable pathway?

And then there’s very, very insular conversations about risk in film, and the cultural makeup of these women meant that they can’t go to auditions or meetings by themselves. You know? Like these really tiny, tiny inclusivity cultural barriers that we don’t talk about.

So I’m like, “Okay, cool, there is no one available to write the show, essentially.” And I was already in this process so I want to fill the room with the right stories, I don’t want to steal stories. I don’t really want to write the show, to be honest. I just am trying to get these pieces together. So yeah, went to a lot of theatre, went to a lot of poetry, spoken word, literary, stand-up comedians. And from there, what I did was I compiled a very, very strong room of women, all Muslim women, who were interested in working on the project but had never really worked in scripting, like film or tv. You know? Because they just had never had the opportunity or had the inkling to do that. They were all working in their own fields.

I think the proudest moment – I always talk about this – is that – got the room together and then didn’t do a thing. You know, met everyone individually, let everyone know who else was going to be in the room. Then I pitched hard. I pitched hard to get the project up. Luckily, ABC had a call-out for digital first comedies. So they wanted short-form comedies to launch on ABC. At the time, I was hoping to create a half-hour pilot to try and sell it as a show. But talking to ABC, I went to a few networking nights and they [said] a show like this might be better suited to short-form because it’s a soft introduction into this world.

I really resonated with that because you know what? Making these writers who have never worked in tv deliver half-hour scripts sets people up to fail. Do you know what I mean?

Of course.

Like match the experience level to the project. So I [thought] short-form would be beautiful. So we re-drafted to be short-form and then I pitched hard, pitched hard, pitched my little heart out. And yeah, [then] we got the call. From there, it was rooms, rooms, rooms. We did a lot of rooms. Aanisa [Vylet] who goes by Randa [Sayeed] now, she changed her stage name.

She was on the team?

Yeah, and it was basically about getting this room together. And we hadn’t cast it yet as well. We were just writers, we were just breaking the story together and writing. Then the practicalities of running the show become a question. ABC really wanted me to ensure that scripts could get to production level. That’s just the practicality of the process, I guess. But I was very conscious that every story tendril should come from the room. Like I never wanted to – obviously I had ideas, [like] there needs to be a gag here, or like what’s an emotional beat that this character can hit? And I just think providing more time for that development really helped because then we were able to have some very – I wouldn’t say “heated” but very nuanced discussions. Because on the outside, a broadcaster or an exec producer is managing a lot of other projects and is just like “What’s happening with the show?” and is like “Here are my notes! Here they are” kind of thing and you have to sift through those and be, “Okay, we keep getting this note back, but what’s our rebuttal as a room?”

I would always bring the notes into the room and [say] “This is what they want. They want a bit more” – just for a torrid example, but they want more salaciousness. You know? And the room would be like, “No, we don’t want to do that.” I was understanding, I really get it. How do we address the note? What is the line of salaciousness that we can hit where we don’t cross lines but we can give them something spicy?

So it was really interesting to funnel that feedback into the project and then funnel back ideas and have this really strong collaboration between all the partners to make sure that we delivered not only a very culturally inclusive show but also delivered a show that also hit a broadcaster’s demographics. And that was also a lot of work, to sit down with the ABC execs and be like, “Tell me what are your core demographics?” ABC, obviously a typically 55+, white. Right? Just hearing things like that and be like, “Okay, how do we appeal to that? Okay, let’s get Bryan Brown in for a character.” (laughs)

Were you told that you have to have a big name? And did you have to have a big white name attached to the project?

No, not at all. I mean, we’d always had the character of Gordon set from the beginning.

I love that his surname is Rudd, by the way.

Yeah. (laughs) Intentional, intentional.

Yeah, totally. (laughs)

Rudd & Sons is the law firm. Again, he was always a key character from the initial pitch because one thing I’m always interested in is making stories locally Australian as well. So same with Tomgirl, there’s influences of Blacktown. Halal Gurls was kind of my love letter to Parramatta and Bankstown. (laughs)

I always had this character of Gordon who was going to be a white older man who was Mouna’s boss. Because this is a working relationship that is replicated a lot in our society. And there are sometimes one-sided conversations or two-sided conversations, and how to navigate not only a woman working under a man but a hijabi woman working under a white man as well, where he’s coming from a completely different part of Sydney, essentially, and not having the burdens of – what his life is facilitated like. He’s a bit more easy-breezy, and Mouna’s carrying the weight of the world on her. So we really wanted that core relationship to speak to the tension of the cultural identity with the Australian identity.

Just so you know, I used to work in the courts so the moment I saw that she was a hijabi lawyer – because I see so many hijabi lawyers in the courts and it’s so awesome. And she looked perfect, she looked exactly like they look in court – you know, with the perfect makeup and everything tucked in place and the colours as well, all those beiges and creams. So when it turned out that Gordon Rudd was her boss as that crusty white old dude which is the entire fucken law profession, I really loved that dynamic. Was that your idea or the writers room came up with that idea?

With Bryan?

No, with the law aspect.

Maybe a bit of both. I think we had always tossed around having a corporate job so it was either going to be business or law. One of the writers actually was a lawyer so, yeah, it felt right to lean into – again, it was that question of let’s be super specific. In the series, Mouna is – I think she’s a paralegal. So we kind of wanted to give her a job that was close to what she wanted but was under this barrier. And it’s actually very similar to Tomgirl, and a lot of people who have talked about the show and asked me about the show have always been – it’s interesting because nothing externally bad happens from a racist perspective, right?

The barrier that Mouna senses from her and her dreams she externalises as racism which is also in the series but we kind of spun it on its head and were like, “Okay but also a lot of this is internalised, a lot of this is her own block, a lot of this is her own apprehension to step into her dreams.” And I felt really strongly about that too. Because that was definitely my personal connection with the series because I really felt a lot of that, stepping into bigger rooms and bigger productions. That feeling of being unworthy.

Yeah, the imposter syndrome, again.

Yeah, again. And that’s where we settled. The last episode was really hard to write because we didn’t know how to end this season and we decided on imposter syndrome. (laughs) Literally.

No, but it was perfect and I really responded to that episode and her instant assumption that she was going to have to solve the problems on her own and take care of her sister and take care of her mother. And that moment where she hangs up the phone and she has that expression of “oh shit” and you can just see her reshuffling all her dreams and her entire life to deal with this problem. And the scholarship was a small – like with the end of Tomgirl, a small moment but it means so much because it makes life so much easier.

And it’s that validation that changes everything, right? That you don’t expect. I think a lot of – at least this is what I went through when I was younger – was rebutting that validation. You know, people being like, “Here’s an opportunity” and you’re like, “Oh no, I can’t take it. Like I don’t know, I’m so not ready for it. Am I worth it?” That whole feeling went into that moment. That was important for me as well because one of the things we always said in the room is yes, we want to make this culturally authentic but we didn’t want to block anyone from watching the show. We wanted to make them flawed and nuanced as humans, too. And we always sought the universal factor in the character dilemmas as well.

Absolutely. I loved how many female names were in the production credits, just one after the other. It was so great.

That was mandated.

By you or by ABC?

No, by us. By me and the other producer. It was a promise we made from the beginning. We should have as much women crew as possible. And again, inclusive conversation. Because some of the cast members we were trying to audition were Muslim women, we needed as many women on the crew to make that a safer space. We need to mandate this and we had to – yes, obviously there were some roles – like a gaffer, for instance.

I noticed that.

Unfortunately, there’s just a lot more male options [for gaffers] than female right now. We’re working hard on changing that but yeah, at the time we did our best.

I really hope that something else develops from Halal Gurls, maybe not by you, maybe by the other creatives. Because, like you said, okay, this was a short-form thing but it could be a long sitcom, it could be a fantastic classic Australian sitcom if somebody would actually make it and give it money.

Yeah, and it’s been exciting to see We Are Lady Parts, that show. We always had ideas for coming back for another season but our first season wrapped up so circular and nice, and it was a big task, and I think a lot of the writers didn’t want to come back as well [because] they were off pursuing their own things as well. I’m always such a big fan of Halal Gurls and I think what’s really impactful is it’s six short episodes that keep delivering. We still get messages, we still get invites to web fests across the world. We still get nominated for awards. We got nominated for a [Screen Producers Award] recently for the show.

Yes, I saw. Oh my god!

Which is unheard of because it’s the 2022 awards and we screened three years earlier. (laughs)

I know, I was like “What!”

I know, I know. The important thing for me was that creating such a strong brand recognition meant that she’s walking off on her own. Do you know what I mean?

Exactly.

She’s existing in the world as her own thing. And all these conversations about cultural inclusivity – and obviously I’m very conscious of the optics of me being male as well, running this show. Yes, I can be defensive and talk about show-running cultural inclusive practices until the cows come home. But there’s still going to be some people who object.

Object to you being in that role?

Yeah, who don’t look at the nuances of it and don’t understand the full picture.

Yeah, well, that’s why you do interviews like this.

Yeah, and I’m very proud of the project that’s walking around on her own.

What did your best friend think of it?

Yeah, he actually was involved as the costume designer. (laughs)

Fantastic. Oh! Tarik!

Yeah!

I noticed his name [in the production credits] and Tarek was the character in the [show]. I was like, “Is that the same?”

Yeah, but we changed the spelling. It was a small thing.

After Halal Gurls, was that when you started shadowing Peter Duncan on Operation Buffalo?

You know, it’s really funny because I first interviewed for Operation Buffalo – at the time it was called Fallout. But I interviewed at Porchlight Films in May that year, 2019. So we had just wrapped Halal Gurls so I was interviewing for this position. I had actually done a writers’ room earlier that year at Porchlight too, so they kind of knew me already. My first time working with Vincent Sheehan who is an incredible producer. And I interviewed and hilariously, I didn’t get the role. (laughs) It’s just hilarious how some of this stuff actually happens. I was very close, I was one of two interviews so practically one of us had to get it.

The other director’s attachment, Sarah Bishop, who is a talented actress. She’s part of Skit Box. She incredible. She ended up getting the director’s attachment and started immediately, started in June. That was fine because I was in the middle of an edit and I went to Palm Springs and took Tomgirl around the world and shot a documentary for Sydney Opera House for the Antidote Festival. So I was doing other things.

All of a sudden, I get this call from the line producer who was like “Hey, can you start next week?” And I was like, “Who is this? Who are these people?” She was like, “Oh, it’s Vanessa from Fallout, from Operation Buffalo. We’d really love to have you as director’s attachment.” It was just one of those weird things where I was like, “Okay, sure, yeah.” And I soon learned – that’s why some of these things do work out for the better for the industry. So when there’s production investment from a screen agency, usually they will mandate that an attachment is paid for out of that money too. So I don’t know which partner it was but one other partner came in and wanted to cover an attachment and they had me in their back pocket.

So yeah, all of a sudden I appeared on the set and it was hilarious because like Peter and Vincent – this was in the middle of production, this was about six weeks in of a very long shoot. I was on the production for about ten, twelve weeks after that. So yeah, I appeared on the first day, it was a full army set. I was trudging around in my Converses in mud, I was like, “Oh my god, I’m really not dressed for this.”

Because where was it shot?

It was shot in Yagoona. The old reservoir, Yagoona Reservoir. It’s an incredible set. Apparently Shang-Chi shot there too, right after us.

Nice.

So I rock up to this set, and Vincent and Peter are both there like [looking very puzzled] “What are you doing here?” (laughs) Like “Oh, you’re here!” I’m like, “Hi, I’m the director’s attachment.” And there was this look of confusion. “What?” You know, they’re in the middle of production, they’re totally dazed. And then a few phone calls, “Yes, we needed to get Vonne in because we needed a second director’s attachment.” There you go.

That was such an incredible experience because to be a part of a show that didn’t demand much of myself or my cultural identity, especially. To see an operation like a very big machine working was incredible, and I took that opportunity to really observe from Peter and Vincent and Tanya [Phegan] to learn as much about the process from a craftsmanship point of view. I didn’t have to validate my identity in terms of being there. I never felt like the diversity hire. I was the guy who needed to assist Peter because I was his director’s attachment.

To walk on that set as well, I’m talking a massive budget, massive set, unbelievable set. To walk on that set as part of the directing team, to command respect from that crew and feel like I’m just skating in here was an incredible feeling. And again there was a lot of psychology around entering a machine that big essentially six weeks into production, finding my place, earning my place, really cementing my feet in that production.

It’s interesting because I wasn’t heavily involved in the writing or the producing at all. I was purely there from a directorial point of view. But to help influence some of that show as Peter’s right-hand man on that – as well as Sarah, we were both attached to him – it was incredible.

So you learnt in terms of managing a crew, managing personalities?

Yeah, it was exactly that. It was incredible to talk to Peter about this stuff too. We got quite close during production, as you do. And to ask him these questions and for him to be so generous with his craft and his advice was really powerful. To find out he had been working on the project for seven, ten years until it had gotten up and sitting on this incredible beast of a show that was – working with Colin [Gibson] who was an Oscar-winning production designer who did Mad Max: Fury Road (2015). All these incredible craftspeople. And to kind of sit alongside the director and help manage that was – yeah, it was incredible. And at the same time, I was releasing Halal Gurls. (laughs)

(laughs) Doing so much. So much.

Yeah, I was literally on that set with my laptop and my phone. Again, [the set] looks like an army trench so it’s like sitting on dirt, just managing the socials for Halal Gurls. I managed the trailer release, the first few weeks of ramp-up, press, and then the actual show dropped. I remember I wrapped on Operation Buffalo – the whole thing wrapped on a Friday at 6.30pm and I jumped in my car super quickly and drove to the premiere of Halal Gurls that started at 7.15.

Wow!

So I just was in such – and oh [now] Halal Gurls and I was like, “Whaaaat is happening?” It was the best time, I had the best time working.

I know Here Out West was kind of happening around that as well. We will get to Here Out West. I know that [the production team for The Unusual Suspects] put out a call for Filipino consultants and you answered the call, and you were part of the development process and you were part of the writers’ room. Now that I’ve watched the whole thing and I watched the Unwrapped special, you were very much part of the publicity campaign as well, weren’t you? You and Melvin [Montalban who directed one of the episodes] – they really put you guys upfront which I thought was bit unusual and quite great.

You know, with film and tv, you’re working on a million things at one time. I had already done two drafts and three sessions for Here Out West in 2018 prior to Halal Gurls. So I first saw that call-out for The Unusual Suspects in May. I think it was the same week I interviewed for Operation Buffalo. I actually did a room for Unusual Suspects prior to starting on Operation Buffalo. It’ s just crazy how – because you’re freelancing, you’re working wherever you are.

With Unusual Suspects, it was such a big process to be part of a show like that from the beginning as well. I think the way I engaged with it was yeah, there was a call-out and I sent my writing sample in, I sent in Tomgirl because I was like, “Hey, Filipino writer, Filipino script, here we go.” Heard back and then kind of didn’t hear back as well. It was “Hey thanks, this looks great” and then four months later, “Hey, do you want to be part of this room?” and you’re like, “Yes.”

Obviously, Aquarius [Films, the production company] has such a powerful reputation and I really love how they – it’s Angie Fielder and Polly Staniford. They’re two amazing powerhouse female producers, very proud of the company they’ve built, very proud of telling female stories, and I walked into that room, being so intimidated. I was like (whispering) “Angie Fielder, oh my god, she’s Oscar-nominated, like this is crazy!” (laughs) You know? And it was great to be part of a lot of different iterations of that show.

Covid hit and it felt like the show was meant to start numerous times but it didn’t. We kept getting delayed and it meant that in a beautiful way, they could pour more resources into development. We always talk about the fact that the way the show ended up is kind of the optimum version of it. And it’s almost positive that Covid had happened because [it] allowed us to do so much more work upfront in terms of development and scripting which the show can only benefit from. So I’m very proud of the project because I actually entered as a freelance writer as part of the writers’ room. And then to be invited to be a co-writer for the whole project and then to be invited to be a producer on that as well was just incredible.

What did the co-producing duties entail?

You know, my advice to any emerging creator or up and coming POC is “Know that the industry is watching everything you’re doing.” You know what I mean? Do your best work at all times, because the industry just loves new projects and new work. At the time when I first entered The Unusual Suspects room, Halal Gurls hadn’t been released. So here I was. No one knew what I was capable of or doing, and Halal Gurls released. And all of a sudden, the producers engaged with the show and they switched tack and they were like, “Vonne can do many things.”

So I came on as producer and it was just the best team to work with because it meant I could really learn from Angie and Polly, and Naomi Just was the co-producer on that too. I could learn from their years of experience, I could learn from them about like budget management in terms of a full tv show. I could also be empowered as a producer but have a very strong safety net to fail. So I could make decisions and then nothing would topple. Australia wouldn’t topple over if I made this decision. (laughs) It was like, “I want to do this” and people are like, “That sounds good.”

I’m obviously such a big proponent of cultural inclusivity practice and how that can shift a production model. Especially in the lead up to pre-production and within pre-production, I was putting in mandates. You know, it’s a bit of that Halal Gurls imposter syndrome stuff because to be invited to the table in this project and to kind of have free licence to do everything, and it’s like the person stopping me was myself. “I don’t know if I can do that.”

I remember this really instrumental day when I marched into the producers’ room and I [said] “I think we need to discuss translations. How are our process for translations? I have worked on Tomgirl and I have a Tagalog translation that I’m really proud of that I think I can do.” And the producers were there [were] like, “Oh, that’s great. Yeah, let’s do that. Why don’t you talk us through what you did and we can pull the resources together and give you the time and space and energy to do that? And here are the scripts.”

I [said], “Is it okay if we talk about the cast’s fluency in Tagalog?” They were like, “Yeah, maybe we should ask that.” We actually knew about that so here’s what everyone is capable of doing. I just go back to my desk with all my stuff, being like, “Oh my god, wow, they listened. But also, I can do anything. This is crazy.” You know?

That was so empowering so yeah, I developed the Tagalog process, really supported the actors. We had not only four lead Filipino cast but we had a few supporting Filipino roles as well who had very different fluencies, and the characters had very different backgrounds as well. So just talking to them, being part of those conversations, how to shape those backstories. And you know, sometimes scripting can’t fit backstories in so it was about talking. Like Roxanne’s character, for instance, she’s a bit brash, she uses a lot of swear words, her accent is like a Manila-Tondo kind of area. Because my mum’s from there, right? So it’s a bit of a Manila slum area.

Right, right. Because I saw Michelle Vergara Moore [in the Unwrapped special] and she talked about how Roxanne was from the slums in Manila and had made it up [the social ladder] and I was thinking that’s a great backstory that we didn’t get. But yeah, that totally makes sense in terms of her character.

See, these were the things I was pitching and infusing into the script as a co-writer. That backstory is given to the actor and I think she completely changed some aspects, like it’s her turn. I was really working for her. But then to sit down and talk with her and [say] “This is actually what we’ve been discussing in the writers’ room, and this is where we’re sitting with the backstory.” You can see it spark and unlock things in the actor and she really ran with the parts that she needed to. And the same with all the other four, especially the leads who have very big backstories.

Like me and Margarett [Cortiz], the other story consultant who worked on the scripts – she hilariously moved to Tokyo, actually, so there was a lot of Zooming but hey, it’s pandemic rules. But for us to be putting this level of care and nuance into these backstories created the strongest foundation for so much play. And you know, the show is so high energy and fun.

And it was a big production. When I started watching it, I got a bit shocked and a bit alarmed on your behalf. “Oh my god, this is such a big production and Vonne was co-producing on this?” And such big names. (laughs)

(laughs) It was massive. Let me just say that if imposter syndrome was real, I had to get over that very quickly. Like the first few weeks I’m really timid. But after a while, I’m like (snarls) “Miranda! Get in your dressing room!” From a producer perspective, it was such a great team to work with. Angie, Polly, and me – having four producers, that level of collaboration and honestly not just from a cultural perspective. Obviously part of my role was to be a bit of an authority on Filipino representation and I was on hand to help wherever they needed. But when you’re in production, there are some hairy moments when you’re like, “We can’t get that scene, what do we do?”

I remember this one moment, the four producers and the two directors were standing to the side and everyone was [saying] “How do we get this scene? We’ll have to drop this whole storyline if we don’t get this scene.” And I was like, “You know that house where we’re holding cast? Why don’t we use that living room as this character’s living room? And because we’re running with two cameras, let’s put the B camera there and A camera here, and to save time, run the scene together because it’s a video call scene.”

Yeah, yeah, with Evie and the husband?

Yeah. I just remember them being like “But” and I [said] “Look, I think it’s sound because it’s a separate house, no sound bleed. We have two sound recordists, we have two camera teams. I think we can do the call live and film it at the same time.” And they were like, “Go. Let’s do it. Tell everyone. Oh my god, that is genius.” And I was like, “Holy shit.” And that was me just being a filmmaker. That’s actually the most beautiful thing. Angie and Polly were always [saying] this is the fun of being a producer, that problem-solving, when it’s like life or death almost.

Absolutely.

And also working in these incredible houses, these incredible locations in Coogee. And then having Covid [circumstances], the reality of our shooting as well. It was a really tough but rewarding shoot, and I think the whole team really pulled through.

I was going to ask you whether you felt like the diversity hire on that but obviously you didn’t and that’s so great.

I don’t want to speak for Melvin.

No.

But I’m conscious that the conversations outside the production tend to paint things in a darker shade, and it’s like no one really asked me what my opinion was. I don’t want to say I’m the face of the production at all.

No.

All of us were. But I think we all felt – Melvin and I and the cast and every creative on that show felt super empowered at all times, and I think it speaks volumes about the production process. Sometimes I think with a production company that’s so big, like Aquarius for instance, you think they might – I think this is a very big misconception. You think that a production’s like a machine, you just slip a story through and it just spurts out the same thing.

But no, a production is always created from the beginning with a very different structure and a very different process, depending on the story. And I think yes, maybe not every producer works that way but Unusual Suspects was definitely a product of such an intrinsic production model that can be replicated but should be changed for whatever you’re doing.