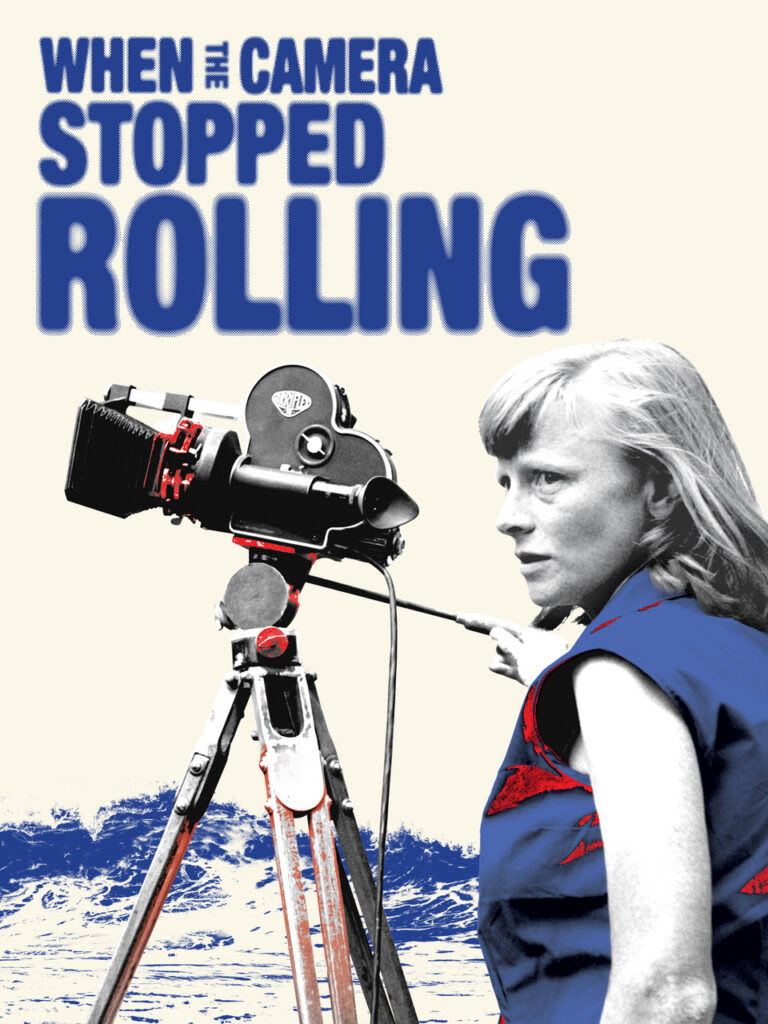

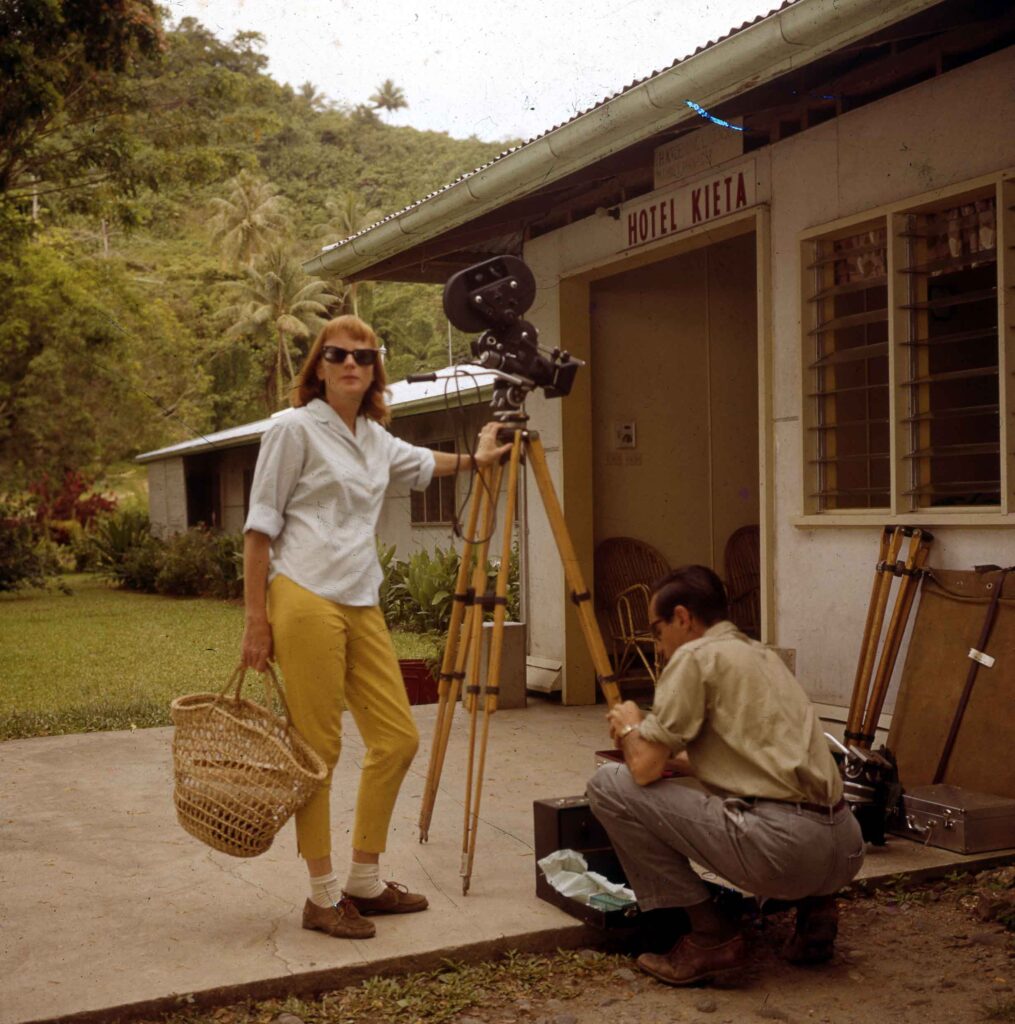

With over 40 documentaries to her name, it’s clear that like Aboriginal filmmaker, Bill Onus, Lilias Fraser is a legend in her own right who has been forgotten by time and the history books. Cinematographer Jane Castle unveils Australian film history with her documentary directorial debut When the Camera Stopped Rolling, detailing her mother Lilias Fraser’s work as a documentarian and cinematographer in the 1950s and 60s.

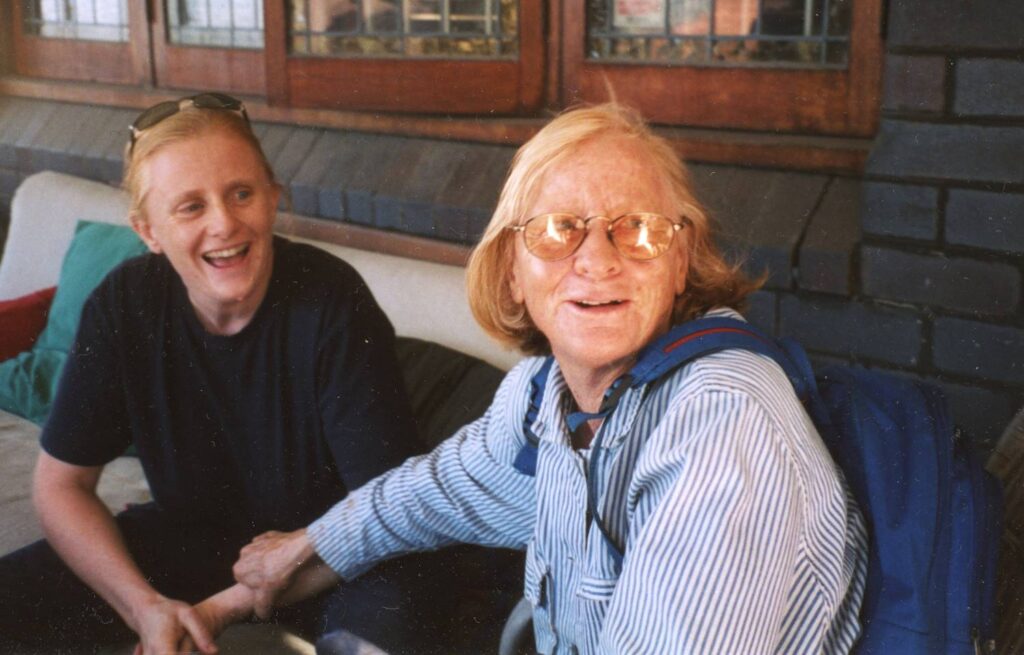

This is an intimate and deeply personal film, and clearly one that is difficult for Jane to present as a filmmaker. Her relationship with her mother is a conflicted one, and within When the Camera Stopped Rolling, we are invited to follow her journey as a cinematographer while she revisits her mothers journey as a filmmaker through stunning archival footage.

In this interview, Jane talks about that familial frustration on film, working with editor Ray Thomas, finding a path through misogyny in the film industry, and so much more.

When the Camera Stopped Rolling is in cinemas from April 21 with Q&A sessions at selected screenings. Visit the Facebook page for more details. When the Camera Stopped Rolling also screens at the Screenwave International Film Festival on May 4th.

Congratulations on the film. It’s really wonderful, very beautiful. I was really moved by it. It’s very easy to get lost in the visuals. There is a lot of personal footage, a lot of family footage, a lot of family photos. What was it like experiencing that again as you’re building up the film and looking at those visuals and just thinking, “Look at what I’ve got on hand here, this is really impressive”?

Jane Castle: It was pretty incredible, actually, because before I started the film, I hadn’t actually gone through the whole archives. I had only really touched the surface of them. As we were going and editing and filming, I was digging through old boxes and finding all these negatives that I’d never seen before and scanning them and going, “Oh my god, this is incredible.”

One of the things I discovered was the wedding photos from my parents’ wedding, (I’d) never seen them at all. They were just in this little slip, this envelope, had never been printed. And we ended up using maybe only one in the end, but they just captured the moment so perfectly. It was like this treasure trove.

There were a lot of dead ends, but there were some amazing things. Some of the material had deteriorated. The paper it had been kept in had stuck to the negatives. I had to take it to the lab and get them to get as much off as possible, and then Photoshop the rest. It was a big piece of work in itself. And including the written material as well, all the letters and stuff. I was reading through those. And, of course, we scanned them and put them in.

With that in mind, how long did this take to make? Because it feels like a film that might have been at least ten years in the making.

JC: Ten years is a good number to put on it. Probably eight years from when we first got funding, but I was working on it for a couple years before that. And if you really go back, the first film I ever made is in the film, when I was seventeen, it was 1981, so in a way, you could say I’ve been making the film all my life.

It took a long time because it was kind of an iterative process, the way we made the film. It was a bit more like an artwork than a film with a script. I mean, we had a script, but really it was just sitting with the material and the timeline and trying things out and me bringing in new material, and then the film spitting out all the material and then “Oh my god, it’s not about this at all. It’s about this. All right.” And surrender to what the film seems to want. It was a labour of love for all of us on the team, actually.

How much did the project shift and sway as the years went on? As you’re saying, it depended on what the project was giving you back. Initially, what did it start off with as opposed to what it is now?

JC: It actually started off as a completely different film. I wanted to make a kind of intellectual film about death, a bit of a spiritual investigation. In fact, the first trailer I made, I interviewed nuns and monks and people who had died and come back, and people who were dying and all sorts of people. We had all these kinds of intellectual explorations.

And the thing was that in the process of doing that, my producer said, “Well, why don’t you just go off and write as well?” And I did. And I wrote this story about my mum’s death. And it became pretty much the opening scene of the film. And then when we started to show this film about death to people, especially funders and Screen Australia, they were like, “I don’t know about all these interviews with these people about death, but I really loved that stuff about your mother, and hey, she’s an Australian filmmaking pioneer.” And then it was just like a no-brainer.

It was really the last thing I wanted to make a film about. Like ugh, my mother. I was still pissed off at being abandoned when she went out on film shoots, and I’m just like, “Oh, giving her more attention, I can’t bear it.” But it was just where the film took us. So it ended up being a really different film and I didn’t want to have myself in it. But the narrative just kept demanding that, to bring the conflict points and to have two characters. My mum’s life wasn’t really enough to have a whole feature length film, so our relationship became the kind of core narrative spine. So yeah, a very different film now than how it started.

What’s that experience like for you, being so open with your life and with your family’s life onscreen?

JC: It’s pretty excruciating, although also satisfying. So it’s a bit of a double-edged sword, but there is the satisfaction in me telling the story of what happened, which I was never really able to articulate. But in doing so, I’ve had to be very revealing and make myself very vulnerable. And that’s, of course, quite nerve-wracking because some people won’t relate to it. But I really had to trust (the audience).

What I found out in the making was that the more honest I got with myself and then was able to put that into the film, the more gripping the film was and the more I think people could relate to it directly because I was being less superficial. So in a way, I was also driven by this terror that the film was going to be a big flop. Like, “Oh my god, I need to make this film work. So I’m just gonna have to be more honest.”

Also there was a point where I could go into kind of gratuitous over-sensationalising of myself and also confessional. I didn’t want to make a confessional film. I was really riding that line. Sometimes I’m like, “Ugh, it’s still a bit confessional. Is it or isn’t it?” It’s tricky to do that vulnerable stuff without going into kind of self-pity or overdoing it. But I think we kind of found the balance in the end.

I think so. That personal look into your life really helps make it very relatable. I’m not a cinematographer, but I can relate to your story in different ways, and that, I think, is the emotional resonance there. For me, as somebody who loves Australian film, this guide into the history of Australian film was appreciated, as you’re saying, your mum was a pioneer. And, pleading ignorance, I wasn’t really familiar with her story. And I think that a lot of viewers will not be familiar with her story. What’s that like, being able to bring her story to light in a way that is very, very tender and caring, and also very much a ‘Hey, people need to pay attention to these pioneers of Australian film history’?

JC: It’s really touching, actually. I guess it also covers a shift in me in the process, because I think if I hadn’t made the film, she’d just be gathering dust in the archives, and no one would know about her. But I didn’t make the film to highlight this pioneer filmmaker, because, as a kid, whatever your parents do, you just think well, “Big deal, whatever. They’re human rights activists, they’re an actor. Whatever.”

My mum was just a filmmaker. And in fact, her making films really annoyed me because it was really chaotic and they kept going away on vacation. But in the process, I do feel this tenderness about her and a new appreciation myself of her importance because I don’t think I even realised the importance of her life and work. And it’s only from getting the reflection back from people after having made the film that I’m realising more and more what an important figure she was, and also the gifts that she passed on to me and my sister in terms of her can do attitude and the trailblazing-ness and not being really affected at all by the systemic kind of shut out of women from the industry.

That certainly for me was really very important. There’s that powerful photo early on where Lilias is there, and she’s surrounded by some of the other figures of Australian film, and they’re all men. And they’re all these people who have become names within the Australian film industry. It’s like what about the women of that period? They existed. Gillian Armstrong was around, we know she existed. What about everybody else?

And then we look at your film history as well, working in different aspects of cinema. I’m curious for you, having worked in major music video productions with some really significant artists and then working on films, it almost felt like when you worked on films, you had to break through that glass ceiling once again. Can you talk about the process of the two different worlds of music videos and film in America?

JC: Yeah, that’s true, actually. See, in Australia on music videos, I worked with my sister, and she was a director, Claudia Castle. We did come up against, in terms of crew, that kind of misogyny, a bit of resistance, a bit of disrespect. But because we were a team, because we had the power – she was producer-director, I was cinematographer – it was easy to overcome.

And then also in the US, it is much more of a fluid area, the music video scene. It’s a bit cowboy, it’s a bit creative. But then in the commercial sector and the feature films, there was a lot more resistance from blokes. I had a lot of personal problems with crew members not respecting me. As a whole, men were supportive. But there were a few that just stand out in my memory. Once a camera assist kept shaming me in front of the rest of the crew, like telling me I didn’t know what I was doing. I had some grumpy-bum grips and gaffers over the years.

Mum was great at giving me advice on that. Because with her, I think she wasn’t as affected as me, she’d just shrug it off. She was much more optimistic than me, I’m a bit more pessimistic and introverted, and she’d just fob them off and keep going her way. So I would draw on her for advice. And the main thing I learned was that I had to actually earn the respect of the guys, initially. And then once I had done that by being professional, being good at what I did, and demonstrating that I knew what I was doing, then they would genuinely come on board and be really supportive. So yeah, it was a work in progress. But I think because of mum’s modeling to me, I’m a bit more resilient than some of the women that I knew in the industry who would really get quite badly affected by the same stuff.

That highlights how important it is to have these role models, to have these figures within the industry itself and within your own family to show the strength and how to be strong and to be able to push against this kind of misogyny that is so prevalent within the industry.

JC: Yeah, yeah, absolutely. Role models are so important. And mum was a role model for the next generation of feminist filmmakers who came up near Martha Ansara, Jeni Thornley, Susan Lambert, Sarah Gibson. At least she was there. Even if she was working in boring old industrial documentary, she’d made like twenty-five films by the time she was fifty. And she was an example that you can get behind the camera and do it.

Let’s talk about those industrial documentaries because the footage that we get to see of them is so fascinating and so engaging. And the subjects that she’s exploring within them are very challenging, certainly for the era as well. These are films, which, at least from my searching, are hard to find. Are they in the archive? Are they in the NFSA?

JC: Well, before we made the film, yes, they were there in physical form, but they hadn’t been digitised. So as part of the process of making the film, we got Ray Argall, who’s a cinematographer and a digitiser to do these beautiful scans of them. So now most of them are available. I’m not sure what the process is to get to see them. They’re not up on a website or anything like that. But hopefully, when the film gets out there, there’ll be more of a demand to actually see that stuff. Because it’s great historical footage, it really gives you a sense of the culture and the thinking behind the times as well as what you see in the frame, which is great. And that beautiful, gritty, grainy 16 mil.

It feels so tangible. There’s nothing like it. It has a warmth to it that is just really beautiful. And I’m fascinated because one of the key things about this film is that there’s no external archival footage in there, it’s all personal associated footage. Can you talk about the decision process behind that as well?

JC: I’m glad you picked up on that, because it was a key decision really early on when I was working with the script editor Alison Tilson, and it was about the authenticity of the film. It was quite hard to stick to that rule. And the rule was that all the archival had to be pretty much either from one of the films my parents or I made or family home movie footage, or photos of them, but to not go outside to just get London in the 1950s footage from somewhere. And it’s interesting that even though it’s not really clear in the film, I think it generates this sense of trust in the authenticity of the material, and that we’re not going to trick you by pretending that this footage was shot by mum. I’m so glad that you’ve noticed that, because I think it’s got an invisible but very powerful impact on the trust that it builds in the audience.

I think so too. And it centres you in your mum’s life and your dad’s life and just reminds us that while this footage was being shot, you were there, this is your point of view. It’s why we watch films, to see somebody else’s point of view. What was the conversation about you doing the narration as opposed to you sitting in front of a camera and narrating to the camera?

JC: It’s interesting you asking me that. It brings back memories. In fact, we did try that really early on. We tried filming me telling the story and being interviewed, and it just was so clunky because I was so self-conscious in front of the camera. So we ended up not filming any new footage of me.

But I filmed a lot of new contemporary footage in the parts where we don’t have archival. It’s those spaces where I’m talking about the past in a very metaphorical sense as well as a storytelling sense. And so the images that I went out and got, they’re from the contemporary world but they have a historic element to them as to what’s in the frame, but also like a non-human element. I think there’s only one person in one shot, it’s a jogger running away in the distance and the rest is quite empty.

They’re shots that allow the audience to drop into the contemplative space of the words because often images can be quite distracting. You’ve got to ride that fine line between the images adding to what’s being said, but not distracting and overtaking from what’s being said. It was a real trial and error process with Ray Thomas and I. Ray was the editor. Often I’d have to go five different times to get the right shot. It was a really painstaking process. It’s not like they’re spectacular shots, but they capture exactly the mood of what I’m saying, and the story.

I want to give a bit of a shout out to Ryan Davis who was the colourist and online editor. He lifted the film visually up, we spent a lot of time polishing the archival, but also the contemporary stuff. There was a lot of thought put into the visuals.

I do actually want to talk touch on the colour aspect of it in a moment. But I want to explore the relationship with Ray briefly as well. What was it like working with Ray as an editor, and what discussions were made there? For me, watching some of his films that he’s worked on (Molly & Mobarak, Rats in the Ranks, Namatjira Project), there is an urgency in his editing that brings us back to the original thesis that you’re working on about death, it reminds us of the importance of life. What an editor does with a cut is so brilliant, what it makes you feel is so brilliant. Can you talk about that relationship there?

JC: I can probably talk for hours about that. There were so many aspects to it. When you talk about this life force aspect, one of the big tussles we had was that I kept wanting to slow the film down in the beginning and put these endless pauses between words for some reason. And Ray over the years, he helped get rid of that. The film has spaces for reflection, sure. But it also has this pace that is such a great momentum, and it keeps pulling the audience forward with the film. There’s never a dull moment. That is a stroke of brilliance because it’s a film that could have sunk down and got kind of stuck in the mud. But Ray kept it going perfectly.

In terms of our working relationship, it was from the very beginning because he worked on it when it was the trailer about death. And we had worked on another TV documentary before that. We’re actually quite different in our approach, and I think that that was a really constructive kind of difference. Along with getting the pacing right, he brought this kind of emotional connection to the material – I was a bit too overwhelmed to even emotionally relate to the film, even though it’s quite emotional. But I was kind of struggling to manage all this material and my own autobiographic material and biographic material of my mum. I was very focused on structure and just pulling the stories out from my insides, that he has this kind of heart relationship with whatever is in the film. And he had a really beautiful relationship to Lilias, my mum, which kept him involved.

He was really committed to me, helping me tell my story as well. He brought the ‘feeling’ element to the film, which I was sometimes lacking. He was also the receiver of all the stuff that I brought, because I brought so much more material than is in the film. He was so loyal to the film. He was loyal to the film above me as a person. That would really help filter out what came into the film and what got chucked out. He was deeply committed to the film, and so that commitment really shone through, I think, in terms of the film’s final authenticity.

It certainly gives the impression that he knew from day dot the importance of telling this kind of story. Touching on that colour aspect, there is a real palette throughout the film that connects the past with the present, a continuity there that is really quite beautiful. What kind of choices did you make when it came to making sure that you honour the original colours of the footage properly and continue that kind of palette throughout the film?

JC: That’s a great question. For some of the material it was – oh my god – really difficult. Because these films, they might be like fifty years old, and from even the neg the colour has drained out, and over time it’s just really thin. So Roen Davis spent a lot of time with some of these films, just getting them to look decent. And then getting the black and white from mum’s early film crisp and dust removal and things like that.

We didn’t have a master plan about ‘okay, it’s going to be XYZ’. But I think again, authenticity was the overriding factor. We definitely shied away from making it chocolate boxy and too beautiful. We didn’t want to just “make it beautiful.” We wanted to make it rich and real. And so I think the footage that came to us really dominated how we approached it rather than the other way around. And of course, I went out and shot stuff.

But yeah, I probably had an unconscious kind of colour palette in my mind, which again was not to – you know, there’s this general push towards making everything look sparkly and beautiful. I was trying to go against that a little bit and go more towards authentic. So I think really just the colours of the footage that was there and what I brought in was the most important factor in deciding the colour palette for the film.

The film received four nominations at the AACTA awards. That kind of recognition from the industry itself and your peers, what does that mean to you as a filmmaker?

JC: Oh, it’s really good. It’s a good feeling to be recognised. And also, along with that, for my mum’s work to be recognised. And it just gives me confidence in that it was a right decision to stick to truth, as much truth as one can muster, that’s available to our conscious minds, and authenticity. And really making films from the heart rather than, you know, trying to make a splash. There are difficult parts of the story, and I think it’s testament to the fact that people are actually hungry for that kind of honesty and authenticity.

I’m also really stoked that the other members of the team – Sam Petty our incredible sound designer, Kyls Burtland our composer, and Ray – got their work acknowledged by their peers. That’s such a lovely warm feeling for me, because they all kind of went way beyond what would normally be required of someone doing that. Way beyond.

Looking at the complexity of Australian film history and pulling from your mum’s history as well, do you have any guidance or pointers for budding cinematographers in the industry? What kind of guidance or suggestions would you have to try and create their own voice on film?

JC: Yeah, it’s a great question because it’s getting more and more competitive out there as the industry becomes more and more democratised by the digitisation of everything. I feel that authenticity and honesty, really, in terms of telling stories, that’s the way to go. That’s the way to connect with audiences.

And in terms of technology, I really encourage people not to get overwhelmed or intimidated by technicalities. It’s easy for that to happen when you start to look at all the specs on these cameras and C log and all sorts of numbers. Mum used to say this: it’s the vision that counts. When they told her that she wouldn’t be strong enough to carry the cameras – and you know, I shot the contemporary parts of the film with a humble Canon 5D Mark II. And yes, it’s got a lot of limitations, but we were able to go beyond those by focusing on composition, light, content.

Keeping it simple, keeping it honest, keeping it authentic. For me, there are so many stories. Any individual in this world has so many stories if they can connect to what’s true in them. So I’d encourage that.

And finally, what does being an Australian filmmaker mean to you?

JC: Hmm. Oh wow, I’ve never thought of that. I think again because I worked in the US and I was immersed in those stories, there is something particular about our Australian culture, one important aspect of which is coming to terms with our colonial history and really the lack of justice still to this day for First Nations people. And I guess it also means with that colonial history and the convict history, there’s an independence of thought, and there’s this can-do attitude that you really see on Australian film crews compared to, say, American film crews. You can get by with a bit of gaffa tape and piece of string, and still we’ve got two Academy Award nominated cinematographers (Ari Wegner, Greig Fraser) and one winner this year. I mean, that’s phenomenal, considering our population size. So it’s that can-do attitude. It’s that rawness and innocence. But also, I do feel we’ve still got a lot of work to do to come to terms with our history of invasion and survival and all that.

How do you feel is the best way we address that on film?

JC: Well, we need to, number one, promote First Nations filmmakers, and let them tell their stories, which is happening more and more. Number one, like back out of the picture. But also to keep talking about that kind of uncomfortable place that we inhabit as this dominant white culture, which includes making films talking about these issues, and by really supporting Indigenous voices to come up to the surface more and more.