Help keep The Curb independent by joining our Patreon.

Operating on a similar level to 2018’s Halloween and 2019’s Doctor Sleep, Nia DaCosta’s Candyman acts as a direct sequel to the 1992 Bernard Rose horror film of the same name, while also ignoring the previous continuity and restarting the story for a new generation.

Watching the 1992 Candyman is fascinating in its ambitious successes and shortcomings. The film actively changes the setting from Clive Barker’s source story “The Forbidden” of working-class Liverpool to the housing projects of Chicago to be more about Black folklore and urban legends that come about in close-knit low-income communities. The story of “the Candyman” is one of racial violence and torment, with the residents of Cabrini-Green repeating his story in fear of summoning his vengeance. They live in fear of the violence to come, almost as if it is truly inevitable. This is still relegated to background as most of the film is about Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen) slowly being seduced by the real Candyman (Tony Todd) and absorbed into his legend as his true love. The original film was written and directed by white filmmakers, and while it touches upon ideas of cyclical violence against racial minorities, it is more interested in being a straightforward horror film. This isn’t a wrong thing, but it leaves open the doors of opportunity.

Such opportunities have been taken on by director and co-writer Nia DaCosta (Little Woods) and producers and co-writers Jordan Peele and Win Rosenfeld. Set in 2019, this new Candyman film is in the same continuity as the 1992 film with Helen’s story now being twisted into a shadow of the truth. Artist Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) explores the leftovers of Cabrini-Green, now gentrified and abandoned, in search of the truth of the forgotten story of “the Candyman” His quest for inspiration for new artistic work leads him down a terrifying path of self-destruction, with his girlfriend Brianna (Teyonah Parris) struggling to understand what is real and what is legend as the Candyman closes in on their lives.

As The Curb has already published a non-spoiler review on Thursday from Hagan Osborne, this will be a spoiler-filled affair. The narrative of this film is a twisted and curving one, with many revelations weaved and tied into its core fabric.

You have been warned.

Because the new Candyman is set in the modern day, things have to change. In 1992, Cabrini-Green was a housing project so riddled with crime and neglected by the state’s government that it became a metonym for housing project errors in the United States. 3 years later, the Chicago Housing Authority began tearing the dilapidated buildings down, leaving only the original two-story rowhouses. The area has since been gentrified into a more affluent neighbourhood with upscale high-rises and townhouses. Chicago has changed, and that change comes with a price.

Both Candyman films have been shot on the real Cabrini-Green area, so when watches both films back-to-back, as I did hours before the preview screening, you see a direct “before and after” picture of what this place is like. It is so dramatic that once again it becomes a main plot point for the film. There is no community here to repeat the legend of Candyman and warn new generations of its presence and power, so what happens? Does a story still exist if people no longer tell it?

When Brianna’s rather disruptive brother Troy (Nathan Stewart-Jarrett) tells the story of Helen Lyle at a dinner party, fans like myself already know how wrong it is. Helen is described as a woman who one day just snapped, beheading a rottweiler, doing a snow angel in its blood, murdering several more random people, before stealing a baby and offering it up as a sacrifice to Candyman at the Cabrini-Green bonfire. No one has been reporting the truth about Helen Lyle in 30 years. The people who know the truth stayed silent for some reason, and now the story has mutated into something wrong and trivial.

Anthony is still captivated somehow. He goes to Cabrini-Green and takes photos of the remaining buildings, and is then told a brief snippet of the Candyman story by one of the last residents William Burke (Colman Domingo). In William’s story, Candyman is not Daniel Robitaille, the Tony Todd Candyman from three films. William’s “Candyman” is instead Sherman Fields, a hook-handed man from the 1970s accused of slipping razor blades in Halloween candy and who is killed by racist police officers in front of William.

Sherman Fields becomes the main version of the Candyman that we then see haunting Anthony in mirrors and committing murders around those who see Anthony’s resulting artwork “Say My Name”, which is a mirror in an art gallery. With this small change of making it a different Candyman, DaCosta and her co-writers open up a brand new possibility for the character, that he is not just one wrongfully murdered Black man but the story is a “hive” of Black men murdered by racists in the same location over 200 years.

There’s a notable sideplot involving a random teenage girl who was at the art gallery, took a picture of Anthony’s piece, and then repeats the seemingly trivial story of “the Candyman” to her ignorant friends. They decide to test the truth of the legend, saying his name five times in the mirror, and they are all promptly murdered while another girl watches helplessly from a makeup mirror’s reflection. The girls think such pain and trauma is something to throw around like a joke. It is not.

As the mysterious murders continue and Anthony’s artwork gains notoriety for its connection to the brutal deaths, Anthony feels himself being pulled deeper and deeper into a fatalistic spiral of possession. Candyman is in every reflection of every mirror, getting closer and closer to Anthony, until finally he is taken completely over, helpless to become one of the hive.

At the same time as Anthony’s progress, the film’s focus starts to shift quite naturally to Brianna’s viewpoint. With every action that Anthony takes, DaCosta cuts back to what Brianna is experiencing and how she is trying to understand the supernatural events that are stealing her loved one away. This unstoppable path of self-destruction begins to remind her of her own artistic father who committed suicide right in front of her. She tries to save Anthony’s life, only for her to fall straight into William’s trap.

The film began with a flashback to Cabrini-Green in 1977, with William being terrified by Sherman Fields at first, screaming for help, only to realise Sherman’s innocence. This doesn’t stop a dozen police officers flooding in and beating Sherman to death. That trauma then permeates William’s life, with his own sister killed while trying out the “Candyman” ritual. He is the only one to remain and tell the Candyman story to Anthony, knowing all about the previous victims of racist violence that have become collected into the Candyman hive. He decides that the story has been dead for too long, and Candyman must live in the modern day. Anthony McCoy has been chosen for this task.

One of the major revelations comes just as Anthony reaches the crossroads of his journey. He discovers that his past was a lie. Thinking he was born on the south side of Chicago, a nurse tells him he was actually born in Cabrini-Green. Anthony goes to confront his mother Anne-Marie, played by Vanessa Williams reprising her role from the 1992 film (and not aging a day in 30 years). Anthony was really the baby boy that Candyman had kidnapped and used as a bargaining tool for Helen Lyle’s soul. Anne-Marie and the other Cabrini-Green residents made a vow that night to never speak the name “Candyman” again, which proved to be the wrong choice. Refusing to speak about pain and horror leaves it to rot in a dark cell.

It was at this point in the film that I, already stunned by the revelation of Anthony’s past, began to make the important connections of the film’s themes. Granted, I needed to watch it again to fully grasp things, but it still makes sense. Candyman is about stories, remembering them, keeping them alive, and how Black stories are so defined by pain and trauma. Anthony’s past and connection to the Candyman legend looping over on itself to create a perfect cycle of sacrifice is his chosen story by the Candyman spirit and the fanatical William. Brianna’s life of tragedy and trauma from her father’s suicide is declared to be “her great story” by a high-class art curator, defining her not by her present talents but by her horrifying past. William lived in the centre of violence and neglect, leading to him setting up Anthony as the new Candyman spirit to continue the story and take revenge on white supremacy.

Everything comes to a head in a complex, sometimes disjointed, but ultimately incredibly effective finale. William mutilates Anthony by severing his right arm and jamming a hook in the stump, the same as Daniel Robitaille. He speaks to truth to how the murders of Black innocents in the same spot throughout history has stained the setting permanently, rotting it from the inside out. Brianna is tied up and posed to be a witness to Anthony’s ascension, but escapes, narrowly misses William’s attacks, and kills him as apparent revenge for destroying her and Anthony’s lives. Anthony collapses in her arms out of sheer pain from his mutilation and bodily disintegration from the Candyman spirit possessing him, only for police officers to burst onto the scene and shoot Anthony dead before he or Brianna have a chance to surrender.

Under arrest and in now in the palm of the white police’s grip, they give her a choice of lying to cover up the racial-based murder or be declared an accomplice to Anthony’s unconscious crimes. She takes the third option. Asking for a mirror, Brianna speaks Candyman’s name four times, with the arresting police officer saying it a fifth time, completing the ritual and unleashing Candyman upon his murderers. We see in reflections all of Candyman’s previous forms and spirits, Brianna goes to confront him, and Candyman transforms into Daniel Robitaille before commanding Brianna to “tell everyone”.

Candyman is a thoroughly complex film filled with metaphors and nuances about the modern state of racial existence, focused into the Chicago environment of gentrification, and focused even further into a supernatural world of physical spirits. Candyman evolves from being a straightforward vengeful spectre to a way of trying to make logical sense of senseless violence.

Our main characters seem to be metaphors for modern Black perspectives on racial violence. Anthony McCoy is an innocent man, possessed by the idea of cyclical death and destruction, ultimately becoming victim to a system he cannot control. It makes more sense to say he was chosen by some higher power than just senselessly murdered. William Burke is the intense anger and “eye for an eye” mentality that many African-Americans feel when yet another innocent member of their community is killed. They cry for justice, feel like it will never come, and some decide that revenge is the only answer. The film does not side with this idea. Nia DaCosta and her co-writers side with Brianna, the other innocent perspective who seems helpless to stop the violence and oppression but has the ability to tell everyone, to repeat the story, and to never forget the names of the victims.

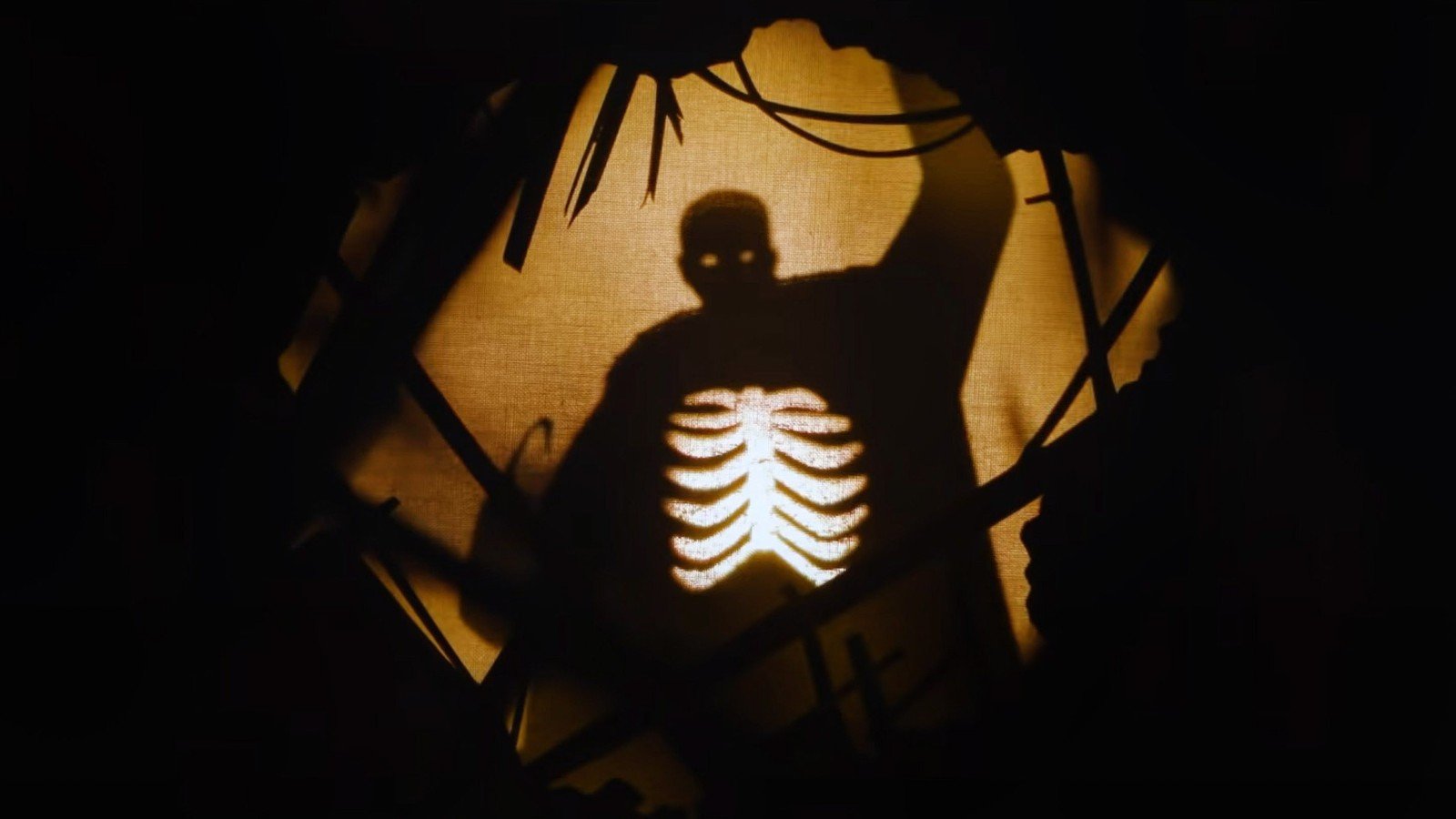

The film is a striking horror vision, captured with sumptuous detail by cinematographer John Gulesarian with Nia DaCosta’s keen eye on how to terrify the audience. How characters are particularly framed in mirrors, some during paramount horror scenes or how Anthony is slowing losing his sense of reality between this world and the one inside the mirror. Several key pieces of framing against the buildings of Chicago are burned into your memory for their aesthetic beauty and thematic importance, and one particularly image of high-rise skyscrapers shot upside down to appear as if they are built from impenetrable fog is one of the creepiest visuals I’ve seen in the genre.

Abdul-Mateen II, Parris, and Domingo give rather intoxicating and incredible performances, operating on wildly different levels. Abdul-Mateen II is at first instantly charming and likeable, and uses this basis to descend steadily into a dead-eyed loss of humanity that one cannot forget. Teyonah Parris is having the run of her life this year, coming out as a breakout from WandaVision and now leading this horror film with the charm, focus and dedication of some of the very best “scream queens” of the genre. Parris also has one of the film’s standout moments, investigating a creepy scenario, opening a door into total darkness, then saying simply “nope” and shutting the door. Domingo is operating on two wildly different levels, at first inviting with a sense of ease at how normal the Candyman story seems, but then changing rapidly into a raving sycophant that elevates above how uneven the turn feels in the writing.

Candyman is not without its flaws. The 1992 film’s main problem is that most of its heavier ideas are surface-level in a white gaze, opting for a more operatic slasher route. The 2021 sequel wears its numerous themes proudly on its sleeve, but with the reach sometimes exceeding the grasp. Brianna killing William feels like an all-too convenient closure to his character rather than a more nuanced approach, Anthony’s confrontation with a disparaging white female art critic is awkwardly placed in the plot, and several comedic moments found in the first 20 minutes fall flat. The film has a wealth of influence, inspiration, and importancewhich thrills at the best of times, and at worst feels like the product of three credited writers.

Nia DaCosta’s sophomore effort seeks to have a richer and more rewarding conversation about racial issues within the context of a disturbing and unsettling horror film, and succeeds. It trusts its audience to look closer and find more terrifying details hidden in the frames, something the very best horror films do well. The performances are all-around excellent, the visual language is vastly effective, and Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe’s score, while operating in the daunting shadow of Philip Glass, works an unnerving spell. Despite its occasional errors, Candyman is a powerful vision of modern horror from Nia DaCosta.

Director: Nia DaCosta

Writers: Jordan Peele, Win Rosenfeld, Nia DaCosta (based on characters from Bernard Rose’s 1992 film of the same name and “The Forbidden” by Clive Barker)

Starring: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, Teyonah Parris, Colman Domingo

For a deeper and more informed look at the commercialisation of Black pain and trauma in horror films, read Carvell Wallace’s piece for The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/10/candyman-horror-movie-black-pain/619825/