When portraying a real life event on film, it’s sometimes easier to dramatise elements to enforce a certain emotional reaction from the viewer. With Michael Almereyda’s Experimenter, the real life of psychologist Stanley Milgram is examined alongside his famed social experiments. Peter Sarsgaard stars as Milgram, while Winona Ryder stars as Milgram’s wife, Alexandra.

Milgram’s notable experiment focused on how people react to authority figures – most notably, focusing on a test where a person was in control of a device which would link to an unseen individual who was to answer questions by the person in control. The device would then shock the unseen individual when they gave an incorrect answer. Unknown to the person driving the device, the unseen individual was not in fact being shocked at all, but instead shouting out as if in pain when the device was activated. While this test is the focus of the opening third of the film, Experimenter then moves into curious territory as it attempts to detail the life of Stanley Milgram.

Often biopics will focus on the life of the individual it is about, rather than the thing that made them worthy of having a biopic created about them. For example, The Theory of Everything was less about the theory of everything, and more about the romance between Stephen Hawking and his then wife. What sets Experimenter apart from other biopics is that it is well aware that the reason why you would sit down to watch a film about Stanley Milgram and his famed experiments is to understand his experiments and why he did them. Sure, you may also be intrigued about what helps create a man like Milgram to invent such experiments, what his childhood was like, what his family life is like, but this is not that film.

What writer/director Michael Almereyda manages to create with Experimenter is an interesting look at the way Milgram’s experiments worked through the eyes of cinema. As is often mentioned throughout the film, one may react to hearing about Milgram’s experiments with a pre-determined outcome of how they would react. For example, with the aforementioned electric shock test, most people upon hearing what the test is would say ‘well, I simply would stop pressing the button when the person cried out in pain’ – after all, we would like to think that in distressful situations we would act with the most positive outcome.

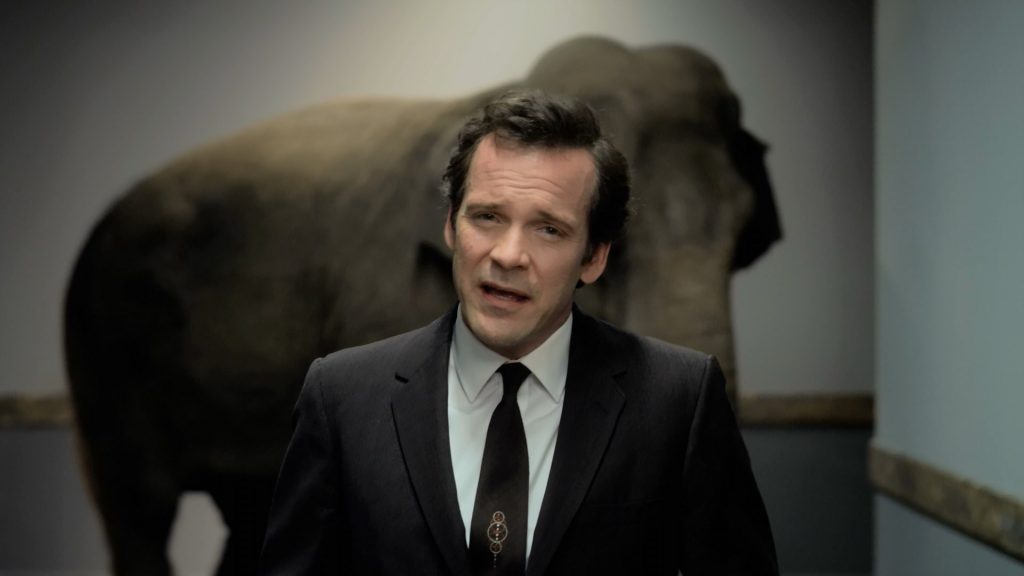

Almereyda uses the avenues of film to force the viewer to always question the subject of the film, as well as themselves. It’s one thing to display what Milgram’s experiment was, it’s another to try and embody elements of that experiment within the film. At first, Sarsgaard’s fourth wall breaking discussions felt out of place and jarring, as if it were a poorly presented soliloquy in a play, but then the realisation that these play like elements are in fact being utilised to put the viewer off centre – to give the feeling that they’re watching something that is just not quite right. The unreality of the film gives way to what feels like stage based histrionics, or rather, sound stage based performances.

Obviously fake beards, projected backgrounds and literal elephants in rooms – Experimenter always lets you know that what you are seeing is false, no matter how many times you are told it is true. It is a cinematic portrayal of one of Milgram’s experiments. At one stage in the film, Stanley and Alexandra get into a car and drive away, leaving a child sitting on the street waving the car away. The shot lingers for a moment, making the viewer feel as if the Milgram’s have just driven away leaving their child on the street. See, the film gives the viewer just enough information about Milgram’s life at just the right moments to trick you into thinking that they’ve just abandoned their child. It’s manipulative, but no more so than Milgram’s tests were in the sense that they were designed to provoke a reaction – even though the result was not the predicted one.

For some, these elements may not work, and that is understandable, this is not a film for everyone. However, it is an interesting film that gives enough information about Milgram to encourage seeking out his studies and reading about the impact of them. The implications of the electric shock study in relation to the Holocaust and the war crime atrocities that occurred during WWII is fascinating, and Almereyda’s script gives enough context to provide an understanding of what it all means. Yes, for the most part this is quite surface level stuff, but intriguingly so it also self-referentially covers the way people will glance at something and feel they know what the entirety of the text means. This is noticed in a short scene where a person on the street accosts Stanley Milgram over his recently published book as he’s talking to an Abraham Lincoln impersonator. When he presses her to find out whether she has read the book, she responds by saying that she only read the Times review – one that was particularly nasty.

This furthers the idea of suggestion and the almost self-reflective nature of the film – especially when considering the way reviews can influence potential viewer’s opinions. (Yes, I’m aware, referring to the self-referential nature of reviews within a film, within a review on that particular film. Inception this is not.) On some level, Experimenter is about taking ownership for your own decisions and your own opinions, it is about reflecting on one’s self and looking at what makes up you as a person – as shown with another of Milgram’s experiments where people have a photo taken and then assess their own portrait, often picking out flaws over perfections in their own face.

This is a fascinating film, one that could quite easily have come undone if Sarsgaard’s portrayal as Milgram were not believable. Sarsgaard is a consistently solid actor, and he’s subtly great here. The way he walks, leading with his head, displays a confidence within Stanley that is reinforced by the relationship between Alexandra. Winona Ryder’s performance is also subtle, but effective. While we never get to know these two people as intimately as other biopics may deliver, there is enough here to get a sense of who they are.

One final moment which is wonderfully darkly comedic is the death of Stanley Milgram. As a man who created an experiment where people have to follow rules, no matter how desperate the situation got, it’s oddly comedic that the film presents Stanley and Alexandra’s arrival at a hospital with a clerk who delivers them a form to complete, even though Stanley is dying of a heart attack directly in front of her. Dutifully, Alexandra takes the clipboard and sits in the waiting room filling out the form while Stanley slowly crumples in his seat. It’s most likely not how Stanley died, but it’s this dramatic license which works so well in reinforcing the ideas that Stanley Milgram had that helped shape psychology as it is today.

Again, this may not be a film for everyone, but if the idea of Milgram’s experiments intrigues you, and you enjoy the performances of Peter Sarsgaard, then it is well worth your while seeking Experimenter out. Be warned – you will no doubt fall down a rabbit hole of reading material once the film concludes as this is some mighty interesting subject matter.

Director: Michael Almereyda

Cast: Peter Sarsgaard, Winona Ryder, Jim Gaffigan

Writer: Michael Almereyda