Wongar, the feature documentary that follows controversial author Sreten Bozic aka B. Wongar is now streaming at the Melbourne Documentary Film Festival. Director Andrijana Stojkovic talks about her experience shooting in Australia, with dingoes, and with the controversial B. Wongar.

Sreten Bozic is an interesting man with an interesting story, how long have you known his story?

I’ve learned about Wongar (Sreten Bozić) by chance. Since I was a teenager I was very interested in Australia and especially in Australian Aboriginals. I was reading a lot about them and their way of life. I was in film school in mid 90s and I came across “Babaru”, a collection of short stories written by B. Wongar, which I liked very much. Some years later, I was looking for other works of B. Wongar for whom I believed was an Australian Aboriginal, and finally found the novel “Raki”. On back of its covers there was a photograph and a short biography on the author and that’s when I realised that he was my countryman actually. What a surprise! And a beginning of this endeavour. I started to look for him or someone who knew him. Through a friend of a friend I got his phone number and one night I called it. It was him on the other side and we talked very long. It took couple of years to do the proper research from the other side of the world and finally in 2005 I had the funds to fly to Melbourne and meet him. Interesting fact is that the name he was given at birth translated to English means “Merry Christmas”.

What drew you to make a film about him?

My big interest in Wongar stemmed from the realisation that a documentary about him provided me with the opportunity to record enormous areas of experience. There is much to be learned from a life in which Australia meets Serbia, a white man cherishes a woman of different culture and skin colour, the 21st century reaches out for the wisdom of a lifestyle 60.000 years old. Wongar’s complex multicultural encounters touch areas in which much rethinking needs to be done.

Given the wide array of experiences Sreten has had in his life, what made you choose to focus on him and his dwelling, without commentary?

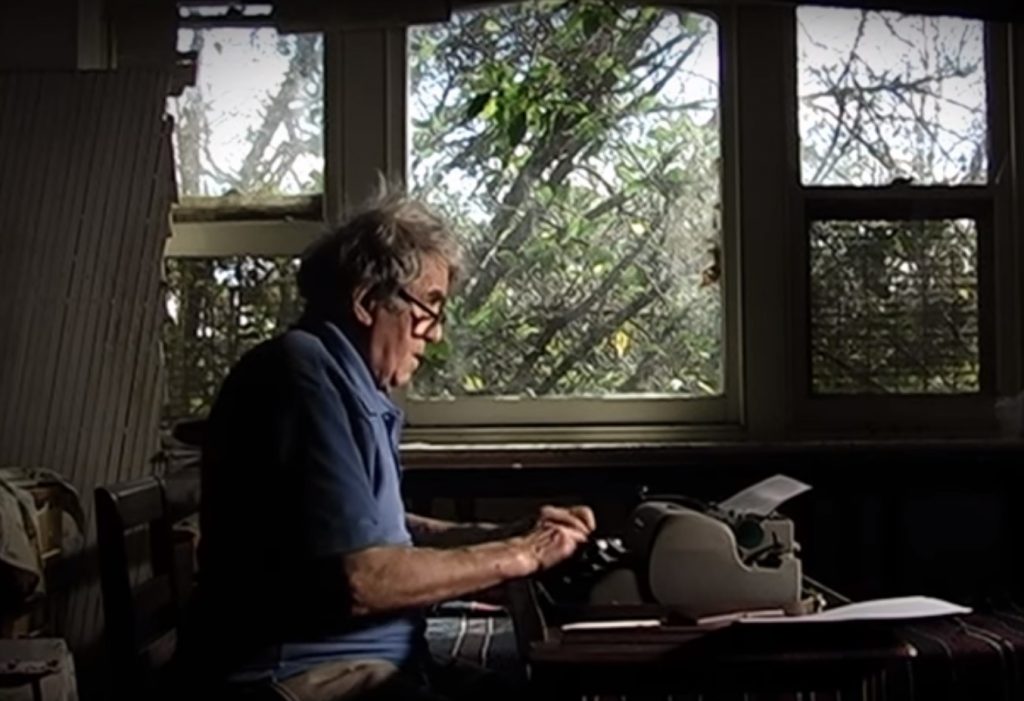

It’s quite demanding for a documentary filmmaker to do a film about past events. Especially events so complex socially, politically and personally. For a long time, I was trying to find a form for it and to be just to him and to his past. At some moment my producer and me where trying to find a co-producer in Australia to be able to get access to archives of the 60s and 70s Australia. After two years of negations and talks with various Australian producers we didn’t succeed and I again had to rethink how I will tell the story. By the time of the shooting in 2008 Sreten agreed to travel with us across Australia by car, to Northern Territory and to places where he lived up there. So, this should’ve been the main “line” of the film during we would discover his life story. This, of course, didn’t happen. And this is the case with many documentaries – the plans you have Life annuls and one has to find another way. When my crew and me arrived to Melbourne we found Sreten preoccupied with sick dingo Timmy and for him it was out of the question to leave the dingo and travel with us. And we only had funds and time for 4 weeks of shooting. So, after couple of days of desperation, I decided to film what I had in front of me. And that is an “autumn” of Sreten’s life and his selfless care for the dingoes for which, he believes, are a connection to his past and his lost Aboriginal family. And this wasn’t insignificant especially since I’ve witnessed how Sreten’s connection with dingoes is earnest and somehow magical. So, I’ve decided to have a long and intense gaze on Sreten and his daily routines believing that part of it will get across to the audience. And I believe it did. The ending text which gives dramatic information about who he actually is and what was his past life like, is leaving big impression on the audience. Many people wrote to me couple of days after watching the film and saying that the film works like and avalanche – the impression grows and grows with time.

How long did the shoot take? Were the animals well behaved at all times?

The crew and I were there a little bit more then 4 weeks. One week we filmed in the Northern Territory and the rest at Sreten’s home. Dingoes are wonderful animals and we never had any problems with them. Well, maybe the only problem there was that they were so alert to our presence so they were not completely “natural” in our frames. Dingoes are lovely but not so much trusting creatures. We had to be respectful of their space and routine. Often during Q&As I ask audience how many dingoes Sreten lives with and very few times I get the correct answer. And I believe this is good because the facts subside to the emotions.

When shooting in the NT, did you speak to any Traditional Owners or Elders about the shoot? If so, did they share any insight into Bozac’s time there?

Besides obtaining the license to enter the NT and film there we also had to obtain a permit from the Elders in Oenpelli (Gunbalanya). And not only for filming but also for staying there and “disturbing” the life of the settlement and its people. We got it, luckily, because the oldest man knew of Sreten and recognised him when we showed Sreten’s novels. All the people of Oenpelli were generous giving us their time and letting us shoot their life but it was very difficult – impossible – to persuade them to talk in front of the camera.

Bozac read passages from his publishing’s throughout the film, did you choose them, or did he? What was the significance?

Part of my research was to read all Sreten has published. And not only once. So, I’ve marked many passages of his writing previously and of course asked for his approval. Sreten didn’t have any objections about my choice. Many are not in the film, though. But I have a great collection of his readings and I cherish them. All the passages I chose to use in the film are told by characters which are Aboriginals and also these passages are about disappearance or searching or going a way to find someone or loneliness. It’s because Sreten himself has been for many years searching for his lost Aboriginal family.

At the end of the film, it says that Bozac wrote articles about the treatment of Aboriginal people, Have you seen examples of these? Are they available anywhere?

Sreten’s home is kind of an archive. He collects and keeps a lot of newspapers, books, publications and art that has to do with Australian past, especially XX century. I was privileged enough to peek into some of the numerous boxes which hold these “archives”. One of the Sreten’s articles I came across was published in “Smoke Signals” – magazine of the Aboriginal Advancement League. I’m sure there are copies that can be found in public archives or elsewhere.

The dancers in the film were the Will Shake Spears group, as credited, was their dance in relation to anything in the film, or any of Bozac’s publishing’s?

My intention was to somehow “touch” the Dreaming and cosmology, beliefs of Aboriginal people. And dances are a part of it. And also, dance is a primordial expression of all the cultures in the world. So, I wanted to “submerge” the audience into ritual dances – to make them feel the rhythm and sounds, movements and to give them the fastest path into ancient way of communication. Alister Thorpe and his troupe Will Shake Spear were very eager to help me in my intention. They are a troupe from Melbourne and, at that time at least, used to perform the dances quite often. I wanted to use the as some kind of markers for chapters in the film. We filmed much more of those but just three are in the film.

Are you aware of the accusations of cultural appropriation regarding Bozac’s aka B. Wongar? Was there ever any intention to explore this in the film?

When a filmmaker starts to research a topic or character for the film, this research should be done thoroughly. Other ways the filmmaker can get things wrong or represent them wrongly. So, yes, I read all the critical text and works about B. Wongar and question of appropriation I could find. And I looked for them exhaustively. Mainly they came from academics and mainly from Europe. I believe that the story of Sreten Bozic is authentic. And on the other side, his literature is of quality. He’s a writer of particular style and interesting topics, quite engaged to uncover injustice and social-historical issues of Australia. Are there “romanticized” parts of his biography? Might be. One is certain – his case is unique and worth listening to.

He cited the long-running phenomenon of the Australian literary hoax as cultural appropriation made real, pointing to Helen Demidenko, a Ukrainian author who was actually the English Helen Darville; Billy Wongar, a fake Indigenous writer created by the Serbian Sreten Božić; and Elizabeth Durack, who signed her art with the name of Indigenous man Eddie Burrup.

Thomas Keneally: ‘Cultural Appropriation is Dangerous’ – The Guardian

What has the reception of the film been in Serbia?

Sreten is not very known in Serbia. Just in the last 15 years or even less, his books were translated and published in Serbia. Only in one novel – “Raki” – there’s a character who is Serbian and part of the story happens in Serbia. But this character is connected with Australia. So, Serbian publishers weren’t much interested in his writings. Nevertheless, the film was received quite good. It won a Grand Prix for best documentary at the oldest Serbian film festival and had a cinema release with unexpectedly big number of audiences. We had a lot of Q&As about the film and the media coverage was surprisingly good.

What was Bozic like to work with?

Although it is said that we live in the age when everyone yearns for media attention or is ready to be a star for 15 minutes, this is not my experience. People, most of the people, don’t enjoy being in front of the camera with their lives exposed. It’s a paradox of our days. But great (film) characters – as Sreten actually is – don’t mind that. They feel that they have not things to hide and are willing “to put themselves into the hands” of filmmakers. Sreten didn’t object to my edit or to inclusion of some of the footage. He was very excited about the footage we filmed in the Northern Territory and he was emotional when he was watching it. We developed a trusting relation and I believe this also comes across in the film. For me, personally, it was very rewarding to have met him and been able to make this film.