War stories on film are often focused on the soldiers journey, presenting their path in war as an ‘us v them’ mentality. So rarely do they explore what the ‘other side’ is going through, possibly for fear of humanising them too much and asking us (the ‘good’ guys) to empathise with their actions. After all, what use is understanding the actions of your enemy if it means getting in their head space?

Think of the narrative that Clint Eastwood takes Bradley Cooper’s Chris Kyle through in American Sniper – it’s introspective, but works in the realm of propaganda and jingoism, never questioning Kyle, or allowing Kyle to be a self reflective individual. It celebrates the long idolised figure that is the American soldier. The American dream of growing up and having a wife and 2.5 kids and a house still exists, but it’s been skewed to the point where a career in the military is the way forward, rather than attaining a 9-5 office job in the city. Partly due to this, criticism of the military, or any major introspection, is thrown asunder.

While films like The Hurt Locker, Stop Loss, and Lone Survivor, paint the never ending war in the Middle East as being a solely American operated affair, it’s worthwhile remembering that this is a multi-national endeavour, with soldiers from the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia embarking on battling the ‘war on terror’.

Enter Benjamin Gilmour with his soldier on a journey film, Jirga.

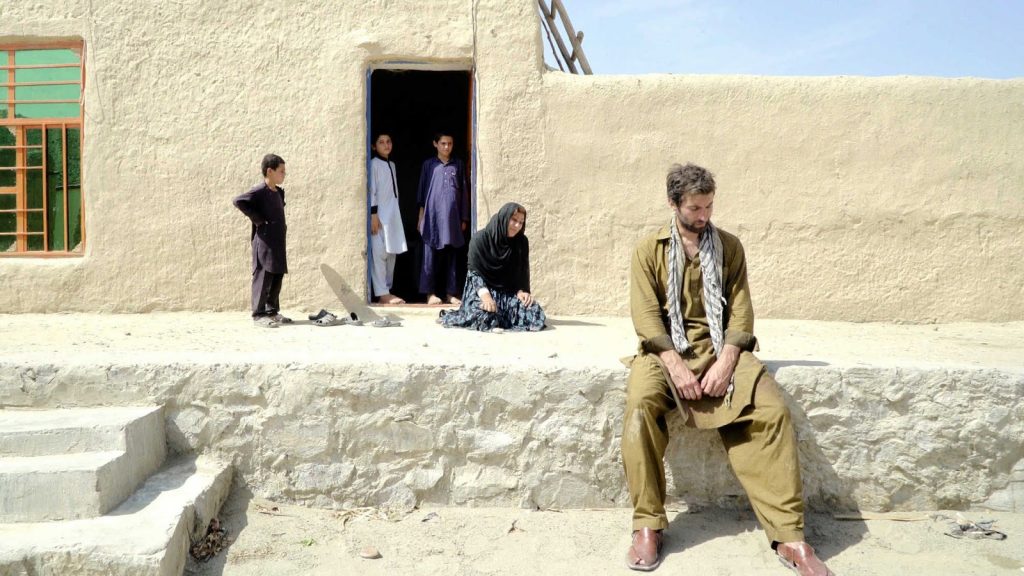

Said soldier is Mike Wheeler (a mesmerising performance from Sam Smith). A former Australian soldier who heads to Afghanistan seeking redemption from the civilian family that suffered a tragedy when Mike accidentally killed their father during a night raid.

The fateful skirmish opens the film, with incoherent night vision amplifying the anxiety and confusion that countless soldiers would no doubt experience in a foreign land. Unknown towns, with languages that they barely understand, and moments of high anxiety, lead to unintentional moments that claim civilian lives. Given that the amount of civilian lives claimed in the war in Afghanistan has been a total of 1,692 in the first six months of 2018 alone, a 1% increase since the war began in 2001. Over 31,000 civilian lives have been taken due to war-related violence, and while the majority of these deaths would be due to Isis, or the Taliban, there is still a sizeable amount of ‘collateral damage’ from attacks by allied forces.

While it’s easy to sit at home in our safe suburbs, scrolling through our news feeds and skipping anything about the trauma being enacted on a mass scale in the Middle East, it’s not so easy for the soldiers who are part of that small percentage who claim the lives of civilians in the war. Gavin Hood’s interesting 2015 film, Eye in the Sky, earnestly tried to explore the complex layers of bureaucracy that drive the military, and in turn, each decision that is made before a soldier (in this films case, a drone operator) pulls a trigger.

Jirga takes the result of the trigger being pulled, the result of years of training and exercises, and asks, what happens afterwards? What happens to the soldier that has to wear this pain for the rest of their life? In turn, Mike Wheeler asks, what does the family that has been torn apart have to live with for the rest of their life, and how can this pain be eased in any way?

Benjamin Gilmour is a patient director. He ensures to humanise the civilians of Afghanistan, rejecting any notion that they should be portrayed as savages, and in turn, portraying them as being wholly empathetic people. These are men and women who have weathered decades of pain and violence, who have found a way forward in life all the while the ever looming spectre of death hangs in the sky like an ever watching unseen bird. They continue to live because what else is there for them to do?

The Jirga of the title relates to an assembly of leaders that make decisions by consensus and according to the teachings of Pashtunwali. It is this assembly that Mike will have to face for them to decide his fate – do they claim his life in an eye for an eye action, or do they accept his plea for forgiveness? This sequence alone is exceptionally powerful, with Smith giving a performance that gives the impression that he has lived in this moment once before. It’s profoundly moving.

Australia rarely steps into the world of modern war films. Whether it’s a cost factor, or simply because the romanticised aspect of World War II brings a bigger box office pull (that Gallipoli dollar goes a long way), or possibly because Australia as a whole is not ready to critically assess its relationship to allied forces in the Middle East, there simply are very few films that grapple with the plight of the modern Australian soldier. And it really should. A film like Jirga is a blessing. It acts as an apology, a mea culpa, for the decades of violence on foreign soil.

Australia treats its soldiers quite differently than that of America. The respect exists for ANZAC’s, with ANZAC day being an extremely sacred day. Yet, there is a genuine concern that this respect merely extends to those who fought in battles that reigned long ago, with many Australians making the pilgrimage to Gallipoli as an act of tokenism (what with Contiki offering a 4 day ANZAC tour of the site). In turn, defence veterans have faced a higher suicide rate than the general population within Australia. Accounts of soldiers battling PTSD have opened up the discussion within the Australian public, and hopefully there is a greater understanding and acceptance of the mental trauma inflicted upon Australian soldiers.

America also appears to celebrate their soldiers in a grander fashion than Australia does. Arguably there is a fair reason to do so, with the military industry being worth over $800 billion. This celebration extends to cinemas depiction of the ‘lone survivor’, or the ‘sole soldier’ taking on the swaths of faceless sand covered enemies and reigning triumphant at the end (albeit with having lost many companion soldiers along the way). For reference, American Sniper was the highest grossing film domestically of 2014, with it furthering the celebration and lionisation of Chris Kyle as a modern war hero.

On the cinematic front, Australia is quieter. Jirga may not be the barn storming film that will encourage a new wave of Australian films that explore the war in the Middle East, but it’s not aiming to be. It plays out like a quiet, contemplative presentation of Yassmin Abdel-Magied’s fabled tweet, ‘Lest. We. Forget. (Manus, Nauru, Syria, Palestine…)’. A mere reminder that Australia’s presence in the Middle East is one that can’t help but leave a mark on the citizens they engage with. A mere reminder that the actions of the soldiers have a ripple of consequences that leaves a mark on both the soldiers themselves and the community at large.

It was a while between films for Benjamin Gilmour, with his last film, Son of a Lion coming out in 2007. Here is hoping that it doesn’t take so long for another film, as there are precious few Australian filmmakers like Gilmour who are working to explore Australia’s relationship with foreign lands in such a manner.

If you are in need of help, please visit the following websites for guidance:

Beyond Blue: www.beyondblue.org.au

Lifeline Australia: 13 11 14

Mates4Mates: www.mates4mates.org

Soldier On: www.soldieron.org.au

Listen to my interview with Benjamin Gilmour and Sam Smith here:

Director: Benjamin Gilmour

Cast: Sam Smith, Sher Alam Miskeen Ustad, Mohammad Mosam

Writer: Benjamin Gilmour