Time is the greatest film critic. We have no absolute way of knowing if something is a “classic” until it has existed for an age. A “modern classic” is a fallacy, a hyperbolic fantasy of a film automatically cementing itself in the public consciousness as being unquestionably great and essential viewing. It’s nice to think that recent films like Everything Everywhere All At Once, Parasite and Paddington 2 have become essential viewing for anyone who truly loves film or wants to expand their tastes. But we just don’t know what will become important in the future.

What is true is that 40 years later, five films can so easily be included in a conversation of the greatest movies of all time, and while we could think about another darker universe where The Chosen, Hanky Panky, Grease 2, Firefox and Megaforce are seen as classic films, we’re discussing the true greats. And they all came out in the same month of June, 1982.

Poltergeist – June 4

Some argue that Steven Spielberg, producer and co-writer of the screenplay, is the de facto director of Poltergeist but that is to severely diminish the talents of Tobe Hooper. Sure, Spielberg’s recognisable themes of middle-class America protagonists facing threats of extraordinary origins, combined with a Jerry Goldsmith score that is as delightful and bright as it is haunting and cold, but Hooper is still at the controls of this horror rollercoaster. Every single scene, much in the same way as his best and worst efforts (The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Lifeforce, respectively), has escalating horror, rendered perfectly with an eye for intricate production design, classical visual effects that still sought to pioneer, and dedicated cinematography. Jaws keeps you focused on the escalating horror with good characters built carefully over time, Texas Chain Saw Massacre terrifies you to your core that more and more horror keeps appearing around the corner, and the two influences mix to terrific precision, inviting you to a house of unique love, Craig T. Nelson and JoBeth Williams instantly becoming those fun movie parents you can easily identify with. Their idyllic setting being possessed by a supernatural force is something quirky at first, like chairs randomly stacking or a certain part of the floor acting like a slip-n-slide. But once Heather O’Rourke’s Carol Anne is taken by the malevolent spirit, nothing is normal. Faces are torn away, portals rip through children’s bedrooms, a clown and a tree try to strange a young boy, coffins and skeletons invade the backyard pool, and giant demonic creatures rip through the beyond, all because of greed. It seems like a typical plot twist now, but the “Indian burial ground” discovery is still shocking today, leading to a multi-dimensional battle for survival that still is an absolute thrill. I still have no idea how they really pulled off the “Vertigo hallway”, but I don’t want to. Tobe Hooper crafted magical terror, ably guided by Spielberg’s knack for story and characters. Poltergeist’s practical effects are some of the very best in all of cinema, and any sequel, remake or imitator will always pale in comparison.

Available to Watch Here:Help keep The Curb independent by joining our Patreon.

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan – June 4

When directors are making sequels to modern blockbusters, they will often be asked about what references or influences they are drawing from. The same response happens every so often, saying they wanted to look at The Empire Strikes Back and Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan for sequels that took things in different directions successfully. That is understatement for the kind of film Star Trek II is. First off, it was my entry to the franchise as a kid, and I proceeded to only see Star Trek films and only got to the shows recently (I’m weird like that). Secondly, it revitalised the franchise far better than the higher-grossing and more high-profile attempted revival in Star Trek: The Motion Picture. It became not only an instantly memorable and beloved film for Trek films due to its more exciting story and connections to the original series with villain Khan (Ricardo Montalban) returning, but it pushed Star Trek into a more complex emotional realm, dealing with death and responsibility far better than any episode of the original series. Not all of its changes are fantastic, the action-centric plot has given way to some of the worst of Trek trying to ape its ship-to-ship finale to mixed results, and those all-red Navy-style uniforms are a sharp stepback from the bold primary colours of the Original Series. At least they’re better than the colour-neutral Pinterest-board style uniforms of The Motion Picture. Director Nicholas Meyer unlocked the possibilities of what Star Trek could offer everybody, with Harve Bennett as screenwriter focusing on a more human struggle for our heroes, while still taking inspiration from Moby Dick. Even with a slashed budget involved reused shots from The Motion Picture, The Wrath of Khan is still a thrilling spectacle that still honours the characters and gives them a focused purpose. The film becomes a better culmination of the time and love fans had for the series with the sacrifice of Spock, a controversial choice already as it originally happened halfway through the film. Leonard Nimoy gives a finale to a character he became the very best playing, and in turn inspires William Shatner to give an equally commendable performance. Even if the franchise still went on, everything could have ended with Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and we still would have got an all-time high for the series.

Available to Watch Here:E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial – June 11

Probably the easiest example of a film becoming an instant classic the second it was released. E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial outgrossed Jaws and Star Wars to become the unadjusted highest grossing film of all time, still maintains a 99% Fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes with both contemporary and retrospective reviews, was the closing film of the Cannes Film Festival in 1982, was the first known film to receive an A+ audience rating on CinemaScore, and director Steven Spielberg was awarded the UN Peace Medal after it screened at the United Nations. It is still of the most instantly recognisable and endlessly touching films ever made that has inspired at least three generations of moviegoers. So I guess it doesn’t need me to commemorate its qualities. Well, in case you were wondering, it still holds up. While Melissa Matheson’s screenplay isn’t the strongest of Spielberg’s most successful movies, leaning often to broader sentimentality, and some of the visual effects have dated (though the attempted fixes made in 2002 deserve to be forgotten), it still works. Spielberg took a screenplay called Night Skies, an attempted sequel to Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which was a horror film about an alien interaction with a family, and splintered the ideas into Poltergeist for the horror and the family, and E.T. for the alien. This move was brilliant because 1) we avoided an unnecessary Close Encounters sequel, 2) we got an excellent horror film in Poltergeist [see above], and 3) Spielberg maintains a de-stigmatisation of extra-terrestrials in movies by giving us a warm, bright-eyed and inspirational figure that unlocks everyone’s inner child. Dee Wallace as the mother of the fractured family, barely hanging to some sense of normalcy, gives an underrated performance, but is still overshadowed by the matured precision of 11-year-old Henry Thomas, a young performance that feels impossible. How can you be this believable as a regular young boy AND rip everyone’s hearts out with genuine emotion? With E.T., Spielberg assured the world that he is THE name in filmmaking, always humble with his gifts and committed to telling the best story possible. Allen Daviau’s camerawork is soft and inviting, a look that many have tried to replicate with little effect, Carlo Rambaldi’s special effects for the titular alien are perfection on the same level as Yoda and the Xenomorph, and John Williams’ score is one of his finest moments and a gentle piece of beauty. E.T. lasts this long because it offers something for everyone, whether you’re the precocious youngest child, the disarmingly mature budding adolescent, the gentle teenager trying to stay strong, the single parent doing your very best, or an adult coming to terms with lost innocence. E.T. will remain 40 years from now holding a special place in the human heart.

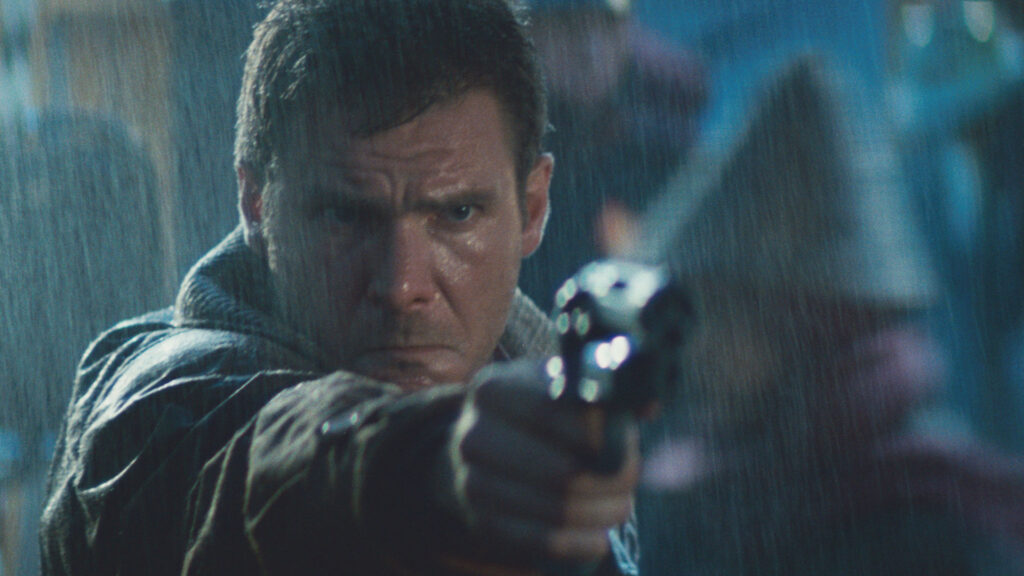

Available to Watch Here:Blade Runner – June 25

Because of the monstrous success of E.T., nothing could stand in its path to total financial domination, blowing out almost every cinematic competitor for at least the rest of the year. The unfortunate side effect of that was good films became lost in the wake, and everything paled in comparison. Science fiction noir drama Blade Runner, the third film from director Ridley Scott and starring a peak Harrison Ford fresh off The Empire Strikes Back and Raiders of the Lost Ark, is misinterpreted and subject to critical derision based on its rough first version. Questionable effects, poor sound design, and a sleep-deprive Ford narration explaining in needless detail obvious plot points and character motivations, it isn’t seen to be anything of note. But there is a great film in there, with Ridley Scott working for the next 25 years to find it and show it to the world. Touch-ups on numerous evocative moments, like the dove flying off into a dark industrial world or Zhora running through the glass windows as she dies, removal of Ford’s narration and the idyllic countryside ending, as well as adding scenes of a unicorn running through a forest, connecting with Ford’s Rick Deckard’s dreams, all become a part of The Final Cut. The film fans and audiences know today may not be the one seen 40 years ago, and that’s for the best. With time comes perspective, and because of its many versions in the interim and fervent cult appreciation, we get something more than a forgettable summer blockbuster wannabe. Scott’s film is inexplicably moving, mostly due to Vangelis’ delicate score and Jordan Cronenweth’s rich cinematography. What it may lack in a comfortable romance between Deckard and Sean Young’s Rachael it makes up for in Ford’s deadpan performance, the dense dystopic world of 2019 Los Angeles, the iconic costume and production design, and the scene-stealing Rutger Hauer giving a soul to a machine. Scenes like the atmospheric opening and the “tears in rain” finale have become iconic in the years since because Blade Runner, with its complex moral centre and fully-realised world, has beckoned cinephiles to look closer and find meaning everywhere, even where the filmmakers had never intended.

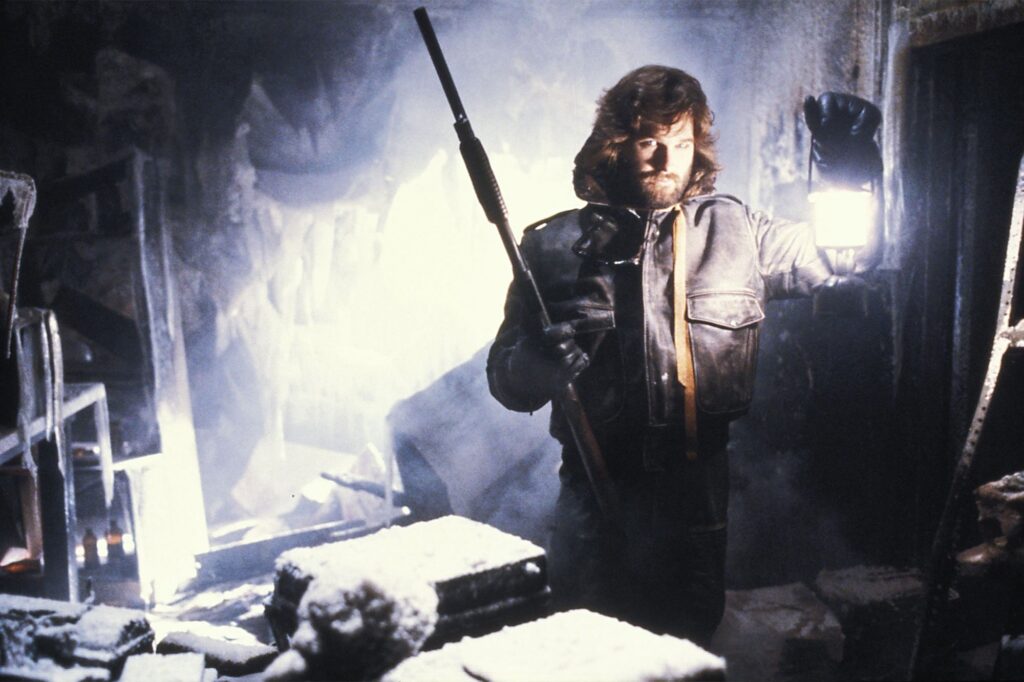

Available to Watch Here:The Thing – June 25

The Thing might be one of the best examples of time being the greatest film critic. Consider the original release of the movie on June 25th, 1982: despite heavy anticipation based on John Carpenter’s massive success with Halloween and The Fog, it debuted to instantly overwhelming negative reviews calling it “a wretched excess”. Making only $19.6 million on a budget of $15 million, it was behind Poltergeist in its fourth weekend and dropped out of the Top 10 in three weeks, making it both not a failure and not a hit. In direct comparison to the monstrous and heartwarming success of E.T., audiences saw The Thing as the worst kind of movie to come out at the time, criticising its “repulsive” practical effects and cynical tone. In the 40 years since, many science-fiction, horror, and general film fans would say that everyone in 1982 was wrong. Including myself. Watching it today, we have no context of E.T. being out at the same time, we don’t live in the kind of economic recession of the U.S. in 1982, and we don’t care for those who wanted it to be more “warm” and “human”. The Thing is cold, dark, nihilistic, and one of the greatest films of all time. It is director John Carpenter’s crowning achievement, proving what he could do with a higher budget and blank checks for special effects, making a remake of a 1950s B-movie that taps into our most basic fears as humans. The claustrophobia and nail-biting tension the film develops by nature of its Antarctic setting and titular alien which, unlike the full-frontal erotic horror of the Xenomorph in Alien, can be anything at all, and deep down is nothing we could ever fathom. Dean Cundey’s camerawork beautifully emphasises how perfect 35mm anamorphic shooting and framing is, capturing blues and reds with stark vibrancy. Ennio Morricone’s score, nominated for Worst Musical Score by the Razzies (who cares), is an evocative masterwork from the maestro, working perfectly in Carpenter’s filmography defined by atmospheric music. Rob Bottin’s practical special effects for the Thing’s transformations are truly horrifying, built out of intense care and love for the art of makeup and effects work, and Carpenter shoots all of it so well you never see or feel its artificiality. A common criticism at the time was the characterisation of Kurt Russell’s MacReady and the other researchers, but one finds that Bill Lancaster’s screenplay, peppered with fun moments like “cheating bitch” and “tied to this f**king couch”, emphasising how normal these guys are, in much the same way as Alien. While they don’t break down crying, the characters steely determination to survive keeps us interested right until the very last second, wondering who is real between MacReady and Keith David’s Childs. I could easily keep going about Wilford Brimley, Donald Moffat, the dog scene, the “stomach jaws” scene which is one of my first memories being scared by a movie, the sound design, the mystery around the Norwegians, the enduring legacy and influence The Thing has had on other sci-fi-horror films, and the ambitions and ultimate failings of the 2011 prequel-sequel, but we’ll stop here. The Thing is my favourite film in this 40th anniversary retrospective, an endlessly rewatchable and eternally rewarding horror experience that remains unmatched to this day. There is another universe out there where The Thing instantly finds its audience, is as big a success as Halloween or Poltergeist, and Carpenter goes on to direct a perfect Firestarter and be welcome in the conversation of great 20th century filmmakers, but that’s just wishful thinking. What we have is near-perfect, and I hope John Carpenter takes solace in knowing that.

Available to Watch Here:Help keep The Curb independent by joining our Patreon.