It has been a difficult year for Australian film with few films making it to cinemas for exhibition. Nevertheless, we cannot give up hope for our stories being told.

Making lists is always difficult and I don’t believe in pitting films against each other in rankings (I do enough judging that it becomes dispiriting to make it into a competitive sport) so in my list I am simply adding titles without weighting my enjoyment. Everything brings something or has resonated with me, or they wouldn’t be chosen.

So, in no particular order I present Australian films I felt made us come alive.

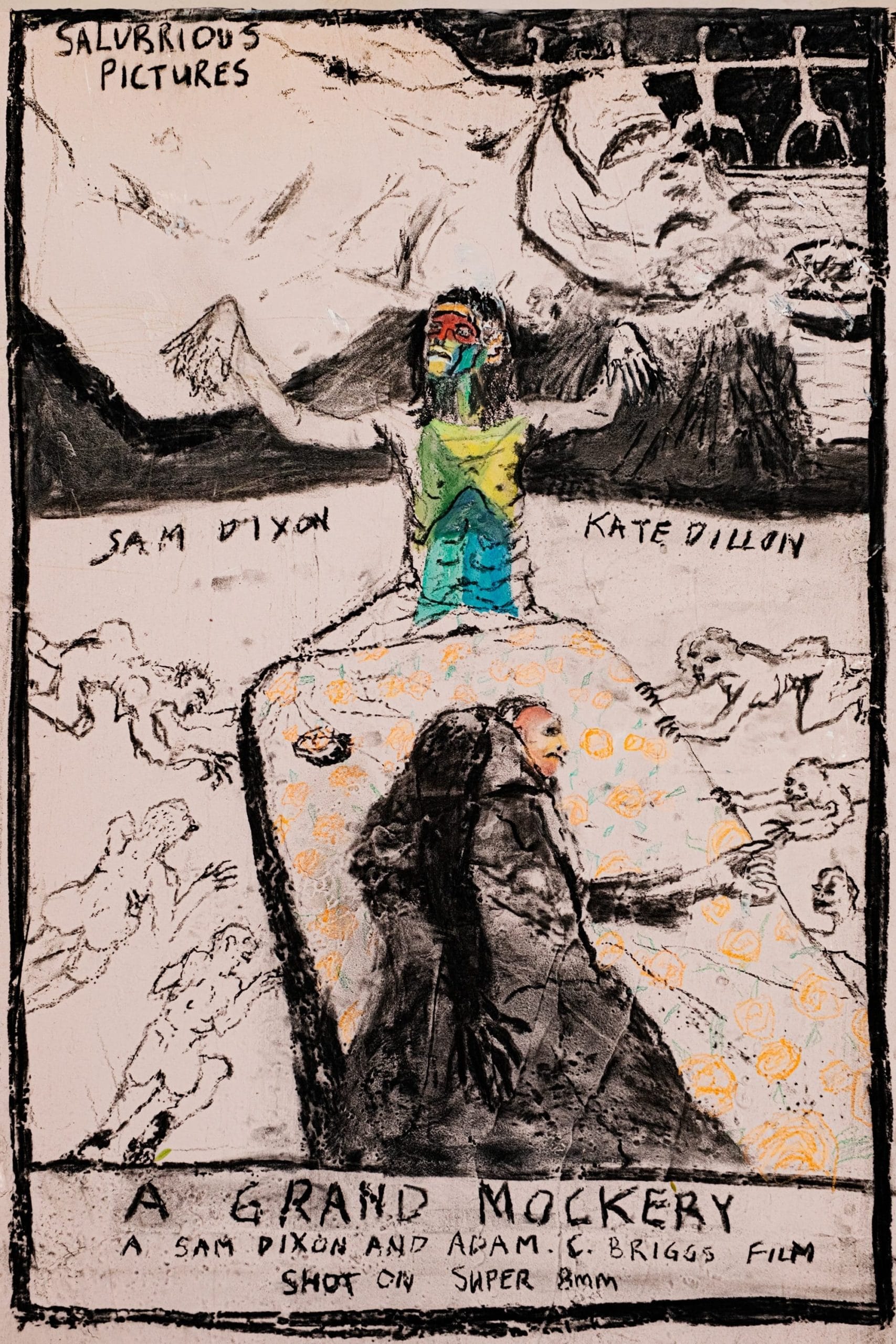

A Grand Mockery

Directors. Adam C. Briggs and Sam Dixon

What do you think of when you imagine Brisbane? Is it the all too clean CBD? Walking across the bridge from the Queensland National Gallery into Queen Street Mall? Is it the Maiwar River? Do you imagine Brisbane at all?

Sam Dixon and Adam C. Briggs present a hidden city in A Grand Mockery. A psychogeography littered with goon bags, filthy group houses, and cemeteries. The film reeks of vomit, piss, and decay. Sam Dixon plays Josie, an alcoholic and depressed being who is haunted by a shadow self and caught in a cycle of physical and emotional abjection. Grainy filmstock captures his decline as he tries, and fails, to make connections to the living. At some point he ‘dies’ but is trapped in a purgatory which is only marginally different to his life.

Seeking to purify himself Josie heads to the hinterlands of South East Queensland and into another purgatorial state. He is becoming a creature of disgust and looks to the undeniably beautiful semi-tropical rainforests and moss-covered rocks to immerse himself in something clean.

It’s difficult to categorise A Grand Mockery. Is it horror? Urban Wyrd? A White Australian folk horror? A ghost story? Is it none of those things or all of them? What it is relies on interpretation. Beautifully inaccessible but also somehow all too familiar, A Grand Mockery exists as a liminal work of psychosis and downbeat determinism.

He Ain’t Heavy

Director. David Vincent Smith

In my interview with Perth based writer/director David Vincent Smith he breaks down his film about being trapped by love for a person who has forgotten how to love himself.

A story of one family dealing with the fallout of mental illness and addiction; and the limits of being able to care for the person inside the disease. Max (Sam Corlett) becomes a violent almost demonic presence in his sister Jade’s (Leila George) life. Trying to protect herself and her mother Bev (Greta Scacchi) from Max’s outbursts has made her put her life on hold. In an act of desperation, she kidnaps Max to get him through detox – as all the programs he went into previously have failed.

Max has committed a violent crime, and in his current state, is violent and unpredictable. As Bev appears lost in her memories of her beautiful son as a child, it falls to Jade to take radical action to ‘save’ all of them. The person she’s trying to save most of all is her present and future self, because Max’s demons have placed her in a permanent carer position where she watches her friends get on with their lives – marriage, children, and careers – all things she has put on hold, so she is available to Max and Bev.

He Ain’t Heavy is as harrowing as it is human. Sam Corlett, Leila George, and her real-life mother Greta Scacchi give honest and layered performances under Smith’s direction. The rawness and honesty of David Vincent Smith’s film is disarming. A blazing debut from an Australian talent tackling difficult subject matter with nuance and grace.

Inside

Director. Charles Williams

Mel Blight (Vincent Miller) was in some kind of prison since his conception. His mother and father were married in one. From a young age he was in some form of institution – and as a young boy he committed a violent, meaningless, and deadly crime. Transferring out of juvenile detention into an adult prison is his painful coming-of-age where he meets two damaged and damaging ‘father figures’ who compete for dominance in Mel’s still impressionable mind.

Cosmo Jarvis plays Mark Shepard, a teen offender who was involved in the rape and murder of a child. Now an adult he is transferred out of maximum security into the prison where Mel is placed. Warren Murffet (Guy Pearce) is an addict. Gambling, booze, self-medicating through drugs – he’s seeking parole so he can reconnect with his son Adrian (Toby Wallace) who was a child when he committed the crime that put him in prison.

Mel is desperately confused. He’s institutionalised but still wants some kind of help to break his cycle of violence and uncontrollable anger. He doesn’t want to be released because he’s not sure he will be able to survive, and he won’t harm someone else.

Murfett and Shepard are both men with a little bit of good in them. But neither truly owns up to what they did and who they are. Shepard becomes a convert to evangelical Christianity and preaches in the prison chapel. His understanding of theology is cherry picked and he believes each person is who God intended them to be – so their personal responsibility for their sins can be washed away by redemption. An abused child who was an alcoholic and petrol sniffer by the age of nine, Shepard believes his path into criminality was predetermined. Yet, there is a sense that if he were given the opportunity he would ‘sin’ again.

Murfett knows what he did, but he is still lost in his self-interest. But he begins to feel a genuine affection for Mel despite weaponizing him to murder Shepard who has had a a hit placed upon him.

It’s a rare prison film that doesn’t paint the corrections department as being inherently corrupt. Inside isn’t pretending prison is helping either. It’s a bad place and simply put, some of the people in there are ‘bad’ both for themselves and others. 40% of the prison population in Australia has an ABI from substance abuse or other trauma. The parole program they are a part of is doing what it can to help the men - but many of them come from situations where recidivism is likely. 51% of the prison population in Australia has received a previous diagnosis of a mental health disorder.

Inside is about determinism, inherited illness, poverty, and the failure of social institutions due to lack of funding, training, and staffing, to catch people before they fall. It’s also about finding a point where someone can learn how to escape the cycles that have imprisoned them.

An extremely effective character study of realistic personalities inside the corrections system.

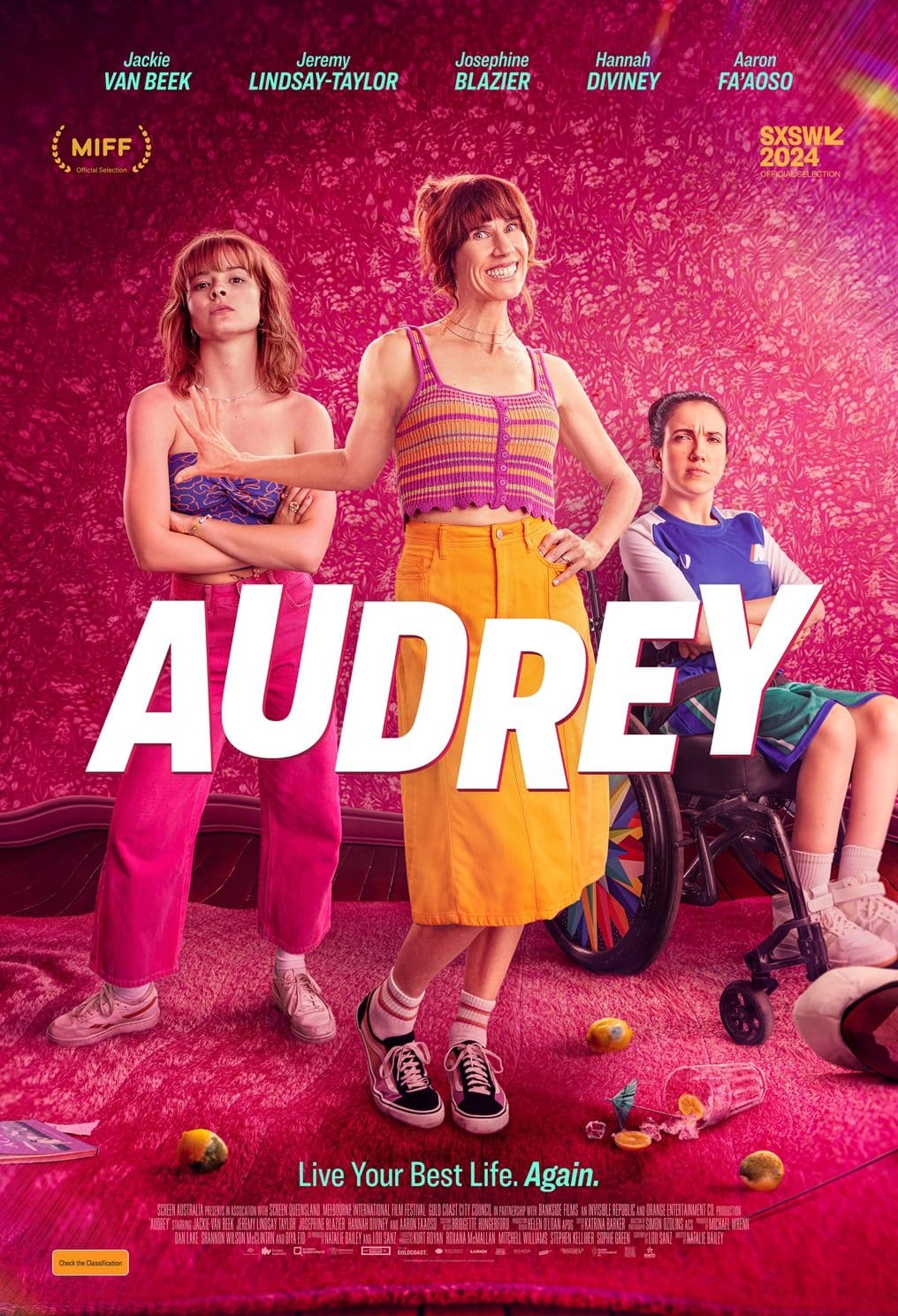

Audrey

Director. Natalie Bailey

Natalie Bailey’s pitch-black comedy imagines what happens when someone creates a monster to live out their frustrated ambitions; and how getting rid of that monster by taking their life (which is a version of your own life) and getting to live it as a second act is so absurdly freeing that allowing the monster to re-emerge is impossible.

Ronnie Willis (Jackie van Beek) is a forgotten prime time soap actress who won a Logie a lifetime ago for her role on Jillaroo (think McLeod’s Daughters). Recently she’s been teaching Monkey Grip in her home acting studio to confused primary school kids and stage parenting her eldest daughter, Audrey (Josephine Blazier) through whom she’s trying to relive her heyday.

Audrey is a full-time job. So much so that her sister Norah (Hannah Diviney) is an afterthought despite her needing basic assistance in the family’s two-story Gold Coast house from her parents to do things like get her wheelchair into the bathroom. Ronnie’s husband Cormack (Jeremy Lindsay Taylor) is more concerned with his erectile dysfunction than he is about Norah, and his marriage is a mess because all anyone deals with day in, and day out is Audrey and her petty self-absorption.

An act of grandiose self-pity and attention seeking leads to Audrey falling from the roof on the suburban home and ending up in a coma. What should be a tragedy turns into an opportunity for Ronnie, Norah, and Cormack to get on with their lives elevated by Audrey’s accident.

Audrey is an audacious and bonkers film with zero moral lessons attached. The only person who comes out of it all with some semblance of sanity and humanity is Norah. A searing satire of fame and competition. Audrey is as mean as its titular character. [link review].

Birdeater

Directors. Jim Clark and Jack Weir

I’ve spent so much time with Birdeater in the past twelve or so months that it quietly became part of my personality (not the characters in the film, but the intention of what Jack and Jim were doing in their examination of private school boys and their hypocrisy).

You can read my review here. “The boys own you,” is a line I will never forget. Essential viewing for anyone interested in coercive control, the crisis of masculinity, and an insight into how little things have truly changed in Australian culture.

The Meaningless Daydreams of Augie & Celeste

Director. Pernell Marsden

The strange complexity of girls and their friendships built to explode with the introduction of desire for men and domesticity.

Girlhood fascinates me, especially the sometimes cruel competitive nature of girls and young women which becomes desperate, dark, and dangerous. A game of make-believe can reveal poisonous lessons learned and misunderstood. Stealing your best friend’s ‘fantasy boyfriend’ during something that seems like play is far from play. It’s hungry and deliberate. It is done out of love and resentment… rivalries that have been taught by adults and filtered into the childhood psyche.

In Marsden’s short a scarecrow becomes a point of contention when Celeste (Libby Segal) tells Augie (Frankie Gillespie McKay) to kiss the Harry Greenwood faced strawman. Celeste then tells Augie she’s pregnant and aids Augie through the birth. When Augie seems comfortable with ‘motherhood’ Celeste decides to steal the scarecrow. Reminiscent of Alice Englert’s 2015 short film The Boyfriend Game featuring Thomasin McKenzie and Morgan Davies, The Meaningless Daydreams of Augie & Celeste is a brief but powerful glimpse into the games girls are taught to play.

Late Night With the Devil

Directors. Colin and Cameron Cairnes

Colin and Cameron Cairnes have been making shoestring budget horror films for a long time. Who would have thought all it took was turning David Dastmalchian into a haunted Don Lane for them to have an international breakout feature?

Using the found footage formula of a television show gone horribly wrong when the host of ‘Night Owls’ Jack Delroy (Dastmalchian) decides to conduct a live exorcism on Halloween in 1977. I have reviewed the film here and spoken to the Cairnes brothers here. Maybe it’s time to rustle up and decent re-release of Scare Campaign!

You’ll Never Find Me

Directors. Josiah Allen and Indianna Bell

“It was a dark and stormy night,” is the cliché opening of many a tale, but in You’ll Never Find Me clichés are constantly flipped and inverted to tell something akin to an Australian M.R. James story of an unexpected return and the consequences of a life lived in hidden evil.

Patrick (Brendan Rock) gets a desperate knock on his coastal caravan door late at night and a young woman (Jordan Cowan) stands soaked to the bone hoping to use his telephone to call for help. The chamber horror piece reveals its intentions slowly and cleverly as the visitor engages Patrick in conversation. Patrick seems helpful at first but as the film progresses his ‘hospitality’ (something he didn’t want to give to begin with) becomes hostile and dangerous. The visitor is seemingly trapped by the storm but there is something supernatural keeping her tethered to Patrick and his hateful “girls like you are begging for it,” rhetoric.

You’ll Never Find Me is written with dexterity by Bell and emanates unease. A brilliant addition to Australian genre filmmaking.

The Rooster

Director. Mark Leonard Winter

Mark Leonard Winter is best known for his work as character actor in Australian cinema. He’s been in high budget features such as Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis and small budget gems such as Michael Bentham’s Disclosure. The Rooster set in a small town in regional Victoria (Daylesford) examines the mental health and lingering guilt of two men.

Dan (Phoenix Raei) is the local copper who is struggling with his divorce and guilt surrounding the acquired brain injury of his friend since his teen years. When Steve (Rhys Mitchell) goes missing Dan is thrust into the orbit of Hugo Weaving’s manic Hermit. ‘Mit’ is wild and unpredictable and is carrying his own burdens, but a tender friendship is formed between the two despite them being on opposite sides of the law.

Mark Leonard Winter was particularly concerned with The Rooster expressing the different manifestations of mental health crises. Mit’s response to the world is to leave it and hide away in a shack in the winter forests of Victoria. Dan’s response is to attempt to formulate a softer and gentler masculinity – but he has no one with whom he can share who is until he meets the wounded drunken larrikin philosopher Mit with all his anger and vulnerability.

Andrew F. Peirce has written about what he believes the rooster in the film represents. My take is the rooster is aggressive masculinity: a Sturm und Drang creature whose life is to crow and fight off others of his kind. His life is also to protect those in his roost. Dan’s battle with his rooster is symbolic of his softness, but also his relationship with Mit who appears to be a rooster.

As the two men become friends it becomes clear that each of them is nursing dark thoughts and are isolated. Yet, for all his wildness, Mit is a positive influence on Dan; and vice versa how Dan’s quiet intellectualism is a salve for Mit. A potent character study of the different ways men present and how through honesty they can help each other heal.

Runt

Director. John Sheedy

John Sheedy’s work is a miracle slice of Australia’s tendency towards being earnestly daggy. The way Sheedy sees childhood and how responsible kids feel in fixing the problems of their small worlds is infused with magic. Like his wonderful H is for Happiness, Sheedy again finds an everyday heroine in the form of Annie Shearer (Lily LaTorre). Once again adapting an Australian children’s literature classic, this time Craig Silvey’s book, Sheedy immerses the audience into a near timeless town Upson Downs which is experiencing drought and dealing with the nefarious Earl Robert-Barren (Jack Thompson) who is essentially a robber baron starving the town of water.

Annie Shearer finds a frightened dog who is run out of town at every turn, and they become fast friends. Runt is a genius sheep hearder and a faithful companion to Annie but will only interact with her. The rest of the family, Jai Courtney’s excellent dad Bryan, her tech savvy daredevil brother Max (Jack LaTorre), her creative mother Susie (Celeste Barber) and her hilarious grandmother Dolly (Geneviève Lemon) are close to losing their farm. When Annie sees a canine agility competition, she enters Runt and with her coaching he wins the run, making her an enemy of the campy villain Fergus Fink (Matt Day).

Runt is a gorgeous tale about overcoming obstacles and being true to who you are. Great support work by Deborah Mailman as former dog trainer Bernadette Box, and Tom Budge as Simpkins who cares for Fink’s prize-winning pooch.

The Shearers are a family you can’t help rooting for. Bryan secretly wanting to be an experimental horticulturist, Susie and her terrible cooking and wizardry with a sewing machine, Max and his limitless imagination, and Dolly deciding it is time to live for herself.

The titular Runt’s shaggy brilliance is a conduit to self-discovery and helps the community of Upson Downs find its strength. Kind lies, gentle affirmations, and deserved come-uppance for the bad guys will make any audience declare “Thank ewe,” to John Sheedy and his wondrous world.

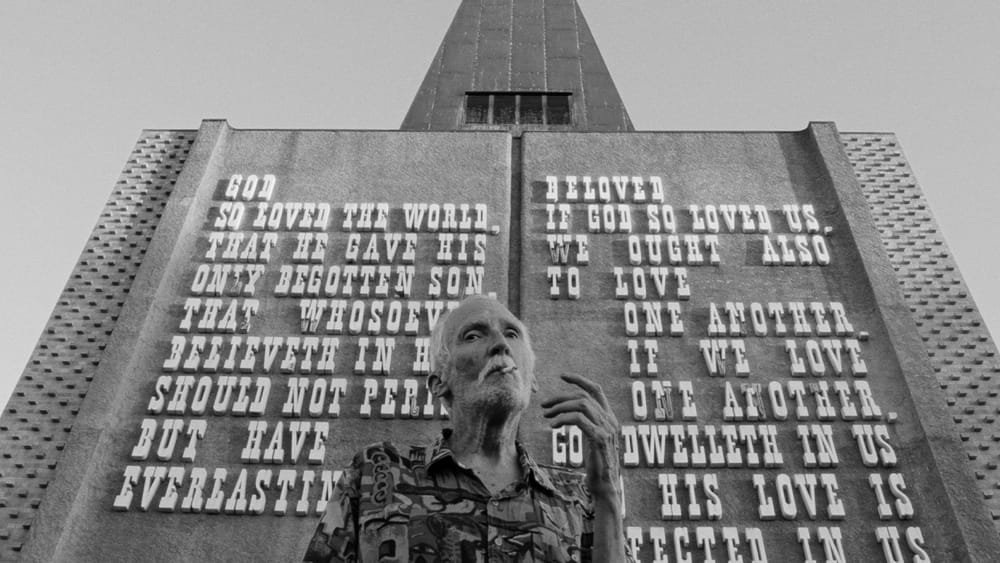

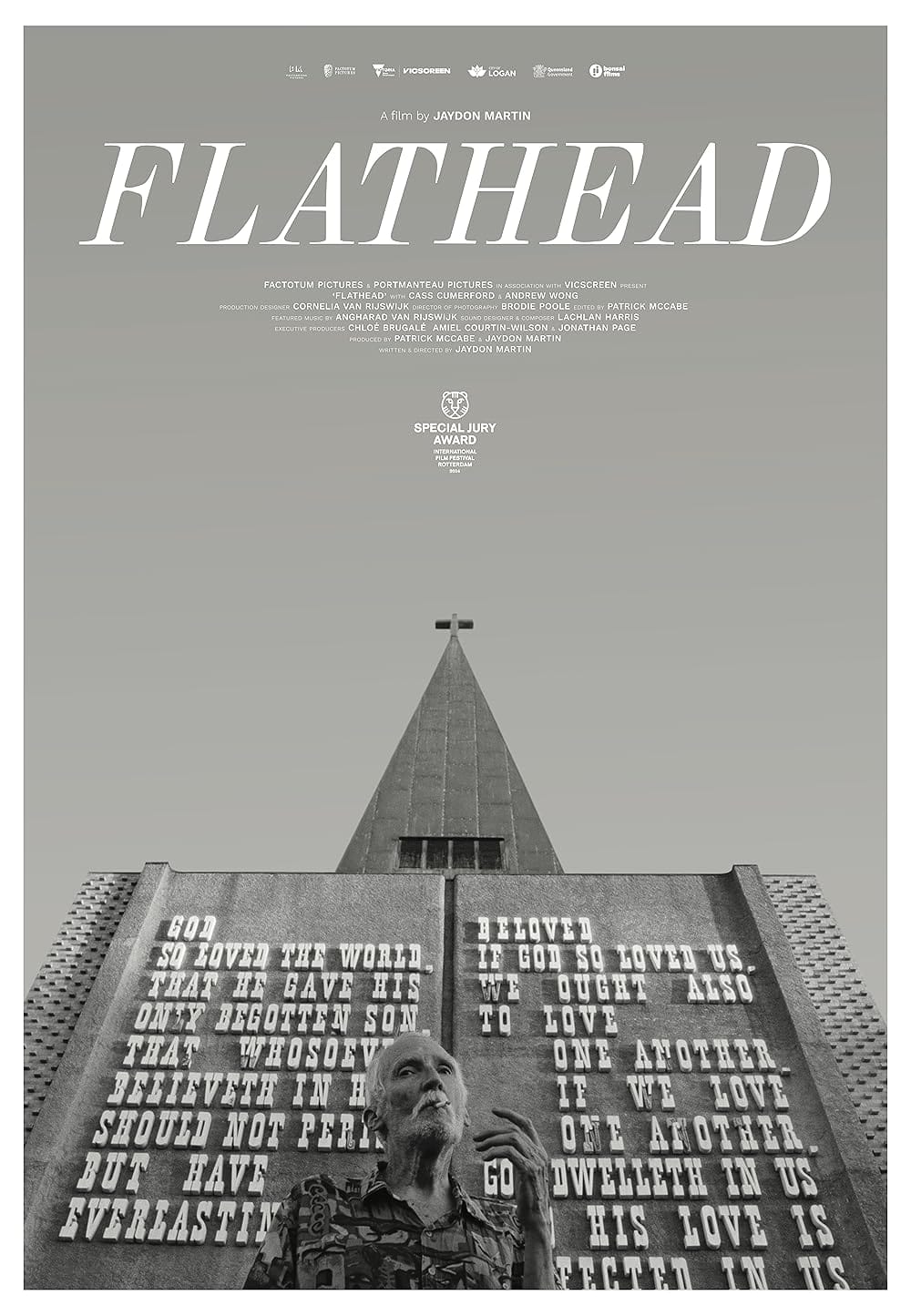

Flathead

Director. Jaydon Martin

When I was at Melbourne International Film Festival I sat behind Jaydon Martin as his name was announced for an award. I wanted to touch his shoulder and tell him how his rumination on death and redemption made me feel transported to an uncanny space – a part of Queensland I know, but also felt was revealed as something I could never truly know. Jaydon had made Bundaberg a Tibetan Bardo. A place between worlds.

We observe Cass with his constant durrie. Andrew Wong with his good humour hiding aching loneliness. Flathead isn’t so much a docu-drama as it is a poem.

Cass wishes he’d been better. He wishes he’d been a proper father. He wishes he hadn’t spent parts of his life as a Kings Cross addict.

Now nearing death, he goes back to Bundaberg in North Queensland. A town known for soft drinks, beer, farming, and food growing and processing.

A community made up of seasonal workers, small business owners, faux yogis, born again churchgoers, pub mates, and farming hoons. Guys who like shooting the shit and shooting things.

Bundaberg under Jaydon’s direction and Brodie Poole’s cinematography is somewhat gothic. There is something eerie about it, and something almost divine. It is broken and beautiful like Cass Cumerford, and the local take-away shop run by Andrew and Kent Wong. There are dreams dying and flourishing in every small corner of Australia.

In the Room Where He Waits

Director. Timothy Despina Marshall

Timothy Despina Marshall’s queer gothic uses isolation as the core of discomfort. Starring Daniel Monks as Tobin Wade, an Australian actor who was about to make his Broadway debut as Tom in Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie but instead is stuck in quarantine in a Brisbane hotel overlooking Roma Street Station waiting for the all clear so he can attend his unbeloved father’s funeral.

As time drags on Toby’s mind starts to unravel as he feels he is being haunted by a ‘gentleman caller’ whose cufflinks, underwear, and clothing keep turning up in his hotel room no matter how many times he removes them. Toby is also dealing with a breakup that he can’t reconcile, and a sense that now he is back in Brisbane he will never leave and end up as no-one. He is also afraid that he was so desperate to be desired by his ex-boyfriend that he can’t perceive himself as possibly desirable by anyone else in the ‘beauty obsessed’ gay community. He begins to be Tom, Tennessee, the fragile Laura of Williams’ play.

Daniel Monks is intoxicating in his phenomenal performance. He’s really the only person “there” — every other interaction is via a screen, a voice, a hallucination, or a set of clothing left behind by someone (or was it?). Raw and authentic, Monks is an undeniable star.

Memoir of a Snail

Director. Adam Elliot

Adam Elliot films are designed to break you into small pieces and build you back up again. Mary & Max, Harvie Krumpet, and now Memoir of a Snail: Elliot’s stop motion clay created worlds are as painful as they are painstaking in their creation.

Grace Pudel (Sarah Snook) sits with her snail, Sylvia, in a garden after the death of her best (and only) friend, Pinky (Jacki Weaver). “I wasn’t always this alone,” she tells Sylvia and begins the story of her life.

Grace shared a womb with Gilbert (Kodi Smit-McPhee) – “two souls, one heart.” Their birth was too much for their malacologist mother Rosie who died afterwards. The twins were raised by their loving but often drunk father Percy (Dominique Pinon) whose move to inner city Melbourne from Paris involved a culture clash and a crash which put an end to his career as a street illusionist. A paraplegic with sleep apnoea and depression, Percy’s joy was his children who he parented as well as he could just as they parented him.

When Percy dies the twin are separated – with Grace ending up in Canberra and Gilbert ending up in Western Australia living in an exploitative religious colony run by the Appleby family. Gilbert had been Grace’s permanent defender – the one who stood up for her when she was bullied because of her cleft palate. Without Gilbert around, Grace becomes more introverted and starts hoarding mementos to compensate for her loss. Without Grace, Gilbert is treated like an indentured servant and finds himself falling in love with Ben Appleby (Davey Thompson), a feeling that is reciprocated but has devasting consequences for Gilbert.

Dealing with topics such as violent conversion therapy, coercive ‘feeders’, alcoholism, depression, anxiety, shame, and poverty – Memoir of a Snail would at first appear to be steeped in miserabilism. But Adam Elliot doesn’t view life in those terms. The entry of Pinky into the film is exuberant – a woman who danced on tables, outlived husbands, drank, ate, travelled the world and passed her memories to Grace is the exquisite, unexpected gift who allows an adult to emerge from her shell.

Featuring the voice talents of some legendary Australians including Eric Bana, Magda Szubanski, Jub Clerc, and Nick Cave and Elena Kats-Chernin’s mesmerising score – Memoir of a Snail is all heart.

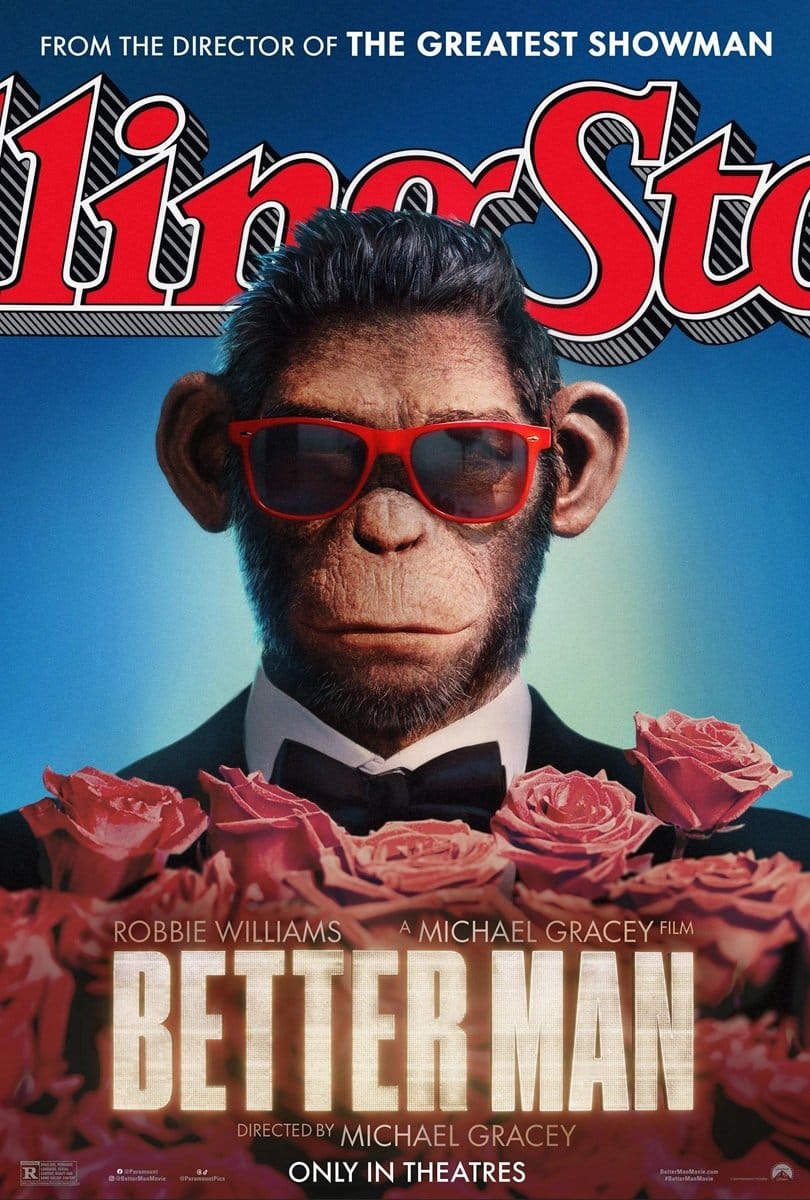

Better Man

Director. Michael Gracey

Even after listening to Take That and watching numerous videos, I still couldn’t hum as single one of their songs. The same goes for All Saints. However, when it comes to Robbie Williams and his solo career – I went all in.

Michael Gracey’s musical biopic of the ‘chav who got everything he ever wanted in life’ might seem like it’s a gimmick film. The gimmick being that Robbie Williams is played by a motion-capped Jonno Davies who represents the pop sensation as a monkey. It doesn’t take long, however, until you stop seeing an ‘unevolved’ chimp and start seeing Robbie Williams.

Beginning with little Robert Williams from Stoke on Trent who desperately wants to connect with his father, Peter (Steve Pemberton) through their shared love of music and traversing his career until his 2005 appearance at the Royal Albert Hall, Better Man is a self-lacerating tragicomedy whirlwind.

Robbie Williams has been more than open about his struggles with depression, addiction, and his appetite for fame. He’s also well aware that a lot of people find him uniquely punchable – and rightly so. He’s a cheeky tosser who accidentally made it big and didn’t know what to do with himself, because ‘Robbie Williams’ was a skin he wore.

Better Man does hit some of the standard notes many biopics do – the rise, the fall, the rise again, and the darkest fall of self-centred and overcompensating egomaniac. At least Williams is self-aware enough to know that for a lot of people the tiny violin of sympathy is as much as they can manage for him.

What Better Man achieves is making self-flagellation, dare one say it, entertaining because Williams is a born storyteller. Shot mostly in Victoria with a few excursions outside of Australia – for example the incredible ‘Rock DJ’ sequence on Regent Street in London is worth the price of admission alone.

Some of the film verges on the horrifying with the ‘Come Undone’ sequence after Robbie quits or is fired from Take That sees him being pulled under by screaming fangirls who emerge from the deep of a lake like sharks. The placement of Robbie’s songs is nigh on perfect – with ‘Feel’ being sung by the child Robert after his father abandons the family for a life of low-rent MC work.

Damon Herriman, Kate Mulvany, Alison Steadman, Raechelle Banno, and Tom Budge are all excellent supporting characters – but the star of the whole shebang is the music.

Unlike Dexter Fletcher’s Rocketman musical biopic of Elton John starring Taron Egerton, there is no claim of ‘poor misunderstood genius.’ Simon Gleeson, Oliver Cole, and Michael Gracey know the audience won’t buy that palaver. What they will buy is Robbie Williams acknowledging he was an arse and making up for it as best he can – and in the end telling the audience he’s great cabaret, so fuck you!