Mia Hansen-Løve has the ability to create seemingly specific and a times highbrow topic and turn them into something relatable to every day living. Although Bergman Island existed in the world of two famous filmmakers taking a holiday to Faroe (home of Ingmar Bergman) it was essentially about a relationship that was falling apart because one partner felt continually overshadowed and undervalued by the other. It was about the need to find and maintain a creative voice outside of a competitive marriage. Perhaps her most personal film, Bergman Island also spoke to many women who are seen as somewhat secondary to their partners.

One Fine Morning may be about a well-educated daughter of a Philosophy lecturer in the beautiful surrounds of Paris, but it is a universal story about the pressures that exist for a generation of women who are caring for both their ailing parents and trying to bring up a child. Sandra Kienzler (Léa Seydoux) has been widowed for over five years. She is raising her eight-year-old daughter, Linn (Camille Laban) alone and making a living as a translator. Her father, Georg (Pascal Greggory) is suffering from Benson Disease, a neurogenerative condition which is rapidly worsening meaning that the time has come where Sandra’s daily visits to him are not enough to ensure his care. Her no-nonsense mother Françoise (Nicole Garcia), who resents being around Georg, informs Sandra and her sister Elodie (Sarah le Picard) that Georg will have to be moved into assisted accommodation – essentially a nursing home, and it will have to be done immediately.

Françoise is not a monster, but she doesn’t much want to be involved in Georg’s life. She makes it clear that she only stayed married to him for the sake of her daughters. She has little pity and less time to give the once brilliant man. Georg has a girlfriend, Leïla (Fejrua Delba) who does not live with him but is always at the centre of his mind. Although Sandra is the person who is there for him most often he is quickly forgetting her.

Between trying to find suitable accommodation for Georg, packing up his book lined apartment, and balancing her job and responsibilities as a mother, there is little time left for Sandra just to exist. A chance encounter with one of Georg’s former students before she has to go to work leaves her quietly devastated. She’s grieving the living, and to an extent she’s grieving herself.

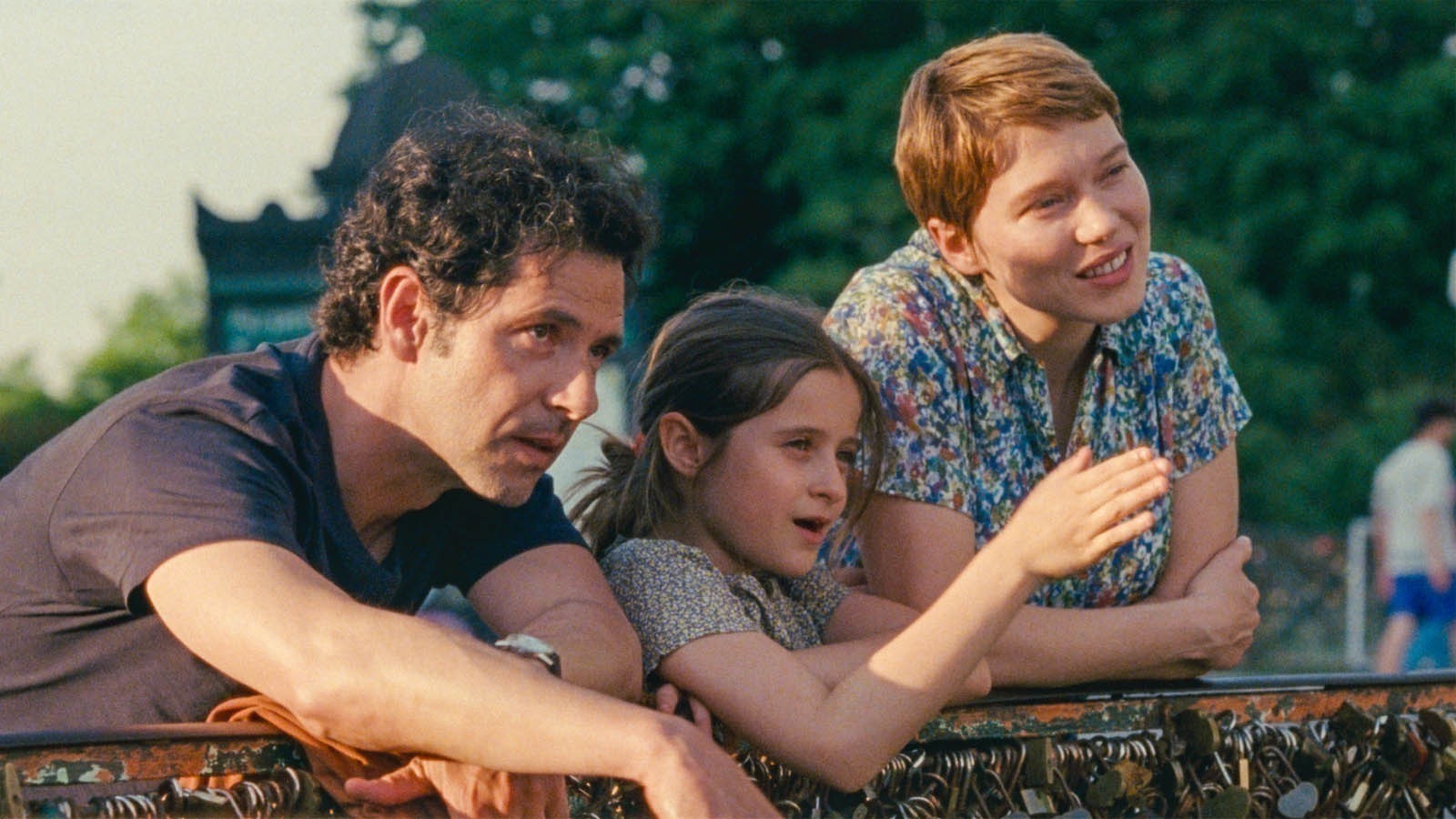

Sandra meets an old friend, Clement (Melvil Poupard) a ‘cosmo chemist’ who travels the world looking for space debris. He has a son around Linn’s age, and also inconveniently, a wife. The two soon fall into a passionate affair which is marred by Clement’s inability to commit to leaving his wife. Sandra wants more, Sandra deserves more, but Sandra isn’t sure how to ask for it any longer.

As Georg’s disease progresses he is placed in a variety of facilities, most are grey and impersonal. They are where people go to die. Anyone who has had a family in a care or nursing home will recognise the spaces and the dread and permeating sense of depression that comes from them. Although Georg’s condition is not Alzheimer’s it is just as cruel, robbing him of his faculties, first his sight which took away his greatest love, reading, and then his memory. He is aware enough that he is losing his abilities and in a diary he was writing when he was first diagnosed he likens it to a Kafkaesque horror. In a particularly melancholy scene Sandra plays him Schubert, but he can’t stand it because there are too many memories crowding his brain – too many associations that he can’t unravel.

Sandra describes Georg’s condition to Clement as him “drowning perpetually” something that is happening to Sandra herself. She is the wife of a dead man, the mistress of a married man, a daughter of a man who is alive but rarely himself. To find the smallest space in all of that, including bringing up Linn who is generally delightful, but has taken to faking an illness for attention, Sandra is lost to herself. What small sections of time she carves out for herself are overwritten by a sense of guilt, not only because she is not there for Georg, but because Clement keeps telling her she has to wait for him to leave his wife. Her sister Elodie has a support structure Sandra does not.

One Fine Morning takes its name from the memoir Georg was beginning to write about his time in Austria and his father’s suicide. As Sandra reads over Georg’s journals she loses him over and over. Hansen-Løve crafts a drama that is universal, we all lose our parents but sometimes we also see them moving away from us whether through age or disease in a manner we cannot halt. To escape the knowledge of this and our own fates just for a moment is intoxicating – which is perhaps why Sandra constantly welcomes Clement back into her life even as he disappoints her. She makes him promise her that if she were ever to develop a disease like Georg’s that he ensures she is euthanised. She does not wish her father dead, but she also knows he is living in limbo.

Seydoux does an incredible job of portraying the emotional honesty of her situation. She is tired, she is overwhelmed, she cries when she thinks no one is looking. Yet she is also searching for life and passion. Sandra may be walking down beautiful streets in Paris, but she can’t really appreciate what is around her until she makes peace with her own limits and properly engages with creating her own happiness. Pascal Greggory is heartbreaking as Georg. He is gentle and pliant, far from a burden except that he is by dent of disease. To be aware, even for small moments, of how much his brilliant mind has been diminished is crushing to behold.

One Fine Morning, also scripted by Hansen-Løve, could be considered a minor work from the director, but it is far from being small. Although the tale is intimate it is a mirror to the experiences of many. Not all of us have to deal with a new and fraught romance, caring for a child, caring for a parent, keeping a job and re-defining ourselves all at once, but there are enough of those common happenings to make Hansen-Løve’s film one that will be deeply felt and true to life.

Director: Mia Hansen-Løve

Cast: Léa Seydoux, Pascal Greggory, Melvil Poupaud

Writer: Mia Hansen-Løve