Platon Theodoris and Nitin Vengurlekar’s wonderfully absurd, hilarious and moving film The Lonely Spirits Variety Hour recently launched at Perth’s Revelation Film Festival, before moving east to the Melbourne International Film Festival. In it, Nitin plays Neville Umbrellaman, a late-night radio host beaming his voice into the world from the solitude of his tiny garage studio. Occasionally guests participate in discussions, including visits from Kenneth Wong (Teik-Kim Pok), Yvette (Alison Bennett), and Neville’s faithful listener Sabrina (Sabrina Chan D’Angelo). Intermixed between Neville’s radio ramblings where he ponders about the ethics of household goods while attempting his best at selling overpriced goods, are moments where we see Neville’s family unite around him in a hospital room in his final moments.

For a film that runs for a tight seventy-seven minutes long The Lonely Spirits Variety Hour is packed full of emotionality and humour, with Nitin’s captivating monologues amplifying that vibe of connection with strangers that I’ve previously written about in relation to Platon’s body of work. There’s a grounded feel that comes from the heightened absurdity of Neville’s dialogue which Nitin delivers with a straight-faced relatability. At once, what he is saying makes no sense and all the sense in the world. This is quite a brilliant piece of work that I resonated strongly with, and I hope that it does so for audiences around Australia.

In this interview, taken ahead of the Melbourne International Film Festival, Platon and Nitin talk about the creative process of translating Nitin’s original stage play to film, about the real-world loss that influenced the narrative, and more. I hosted the Q&A sessions at Perth’s Revelation Film Festival with Platon, Nitin, and fellow creative Brian Rapsey (who edited, shot, and produced the film), and during the Q&A session, the lights in the cinema went out shortly after an image of a panda was on screen. The panda is an animal that plays a major role in Platon’s first film, Alvin’s Harmonious World of Opposites.

The Lonely Spirits Variety Hour is currently screening at MIFF and will be available for audiences around Australia via MIFF Play. It will have its Sydney Premiere with Q&A at the Sydney Underground Film Festival on Saturday 10th September @3.30pm & the Canberra Premiere at Arc Cinema in the National Film and Sound Archive Building on Friday 30th September @6pm.

There is this absurdity to what goes on in your films Platon, but there is a grounded absurdity there as well. Nitin you might be able to talk about this too, what was the joy in being able to work with that field of absurdity here?

Platon Theodoris: Life is weird. I know that word comes up a lot, but some of the best things that I’ve created or explored come from a weird idea that I’ve taken or run with, it comes from real life, you can’t make some shit up. Right? I think if you just look sometimes at the absurdity of life and some of the weird and wonderful stuff that happens [that] we can often overlook, because it can be confronting or we can not talk about, you can just gloss over a lot of stuff. Sometimes the absurd stuff is the most interesting for me.

Which is why I was attracted to Nitin’s stage show because it just came completely out of the absurd and the ridiculous and left me with big belly laughs. I was in stitches. I was crying from laughter during the show and reflecting on Nitin’s show afterwards. For me it’s so ridiculous and funny. The reason why I went so many times to watch it in all its iterations – because Nitin put up the stage show three times – was that I was just trying to figure out a way to bring that on screen – tackling it from a film perspective. Trying to bring a narrative to it. Trying to squeeze it into a three-act structure, to give it some form, which could make it accessible in film language. It was an interesting process and I’m attracted to that.

When I’d made Alvin’s Harmonious World of Opposites, I thought, “Oh my god, this is so commercial. This is so mainstream and digestible.” I thought it was really easy to watch and understand. Little did I know – it took my editor at the time, Dave Rudd, to go, “You’re fucking delusional. This is so left field.” And I was like, “But look! There’s a three-act structure amongst this whimsy and this weirdness. There’s a protagonist and there’s an insightful incident and everything that films need to [be] watchable.”

Nitin, you can take the baton now and talk about your stage show and the narrative structures that I’ve, perhaps, tarnished your work with. [laughing].

Nitin Vengurlekar: My tendency in the theater shows was it was a string of gags, really a string of monologues and Platon took that and added a coherent narrative to it so it would stand up as a film. But on the subject of absurdity, I think part of it comes from this focus on loneliness and being awake in the wee hours of the night and where your mind goes at those hours. The thought processes, the trajectories and tangents that your mind goes on at those hours in that situation where you’re by yourself and there’s nobody else around. So that’s part of where the absurdity comes from.

To elaborate on that the show, when I started writing the stage show [it] came out of thinking about what I used to do as a kid and as a teenager in those hours of the night at 1am, 2am when there were only five channels on television, and on four of those five channels was the Home Shopping Network. They had the same show on every channel, you had no choice but to watch the Home Shopping Network. And then after that they had This Is Your Day with Benny Hinn, and all the televangelists shows. And so the time of day it was at nighttime and then watching this mixture of commercialism and spiritualism, they were both selling something. The Home Shopping Network was selling new diamond necklaces, or kind of the things that you used to get the little bits of fabric off your shirt, lint rollers.

Then the spiritual shows were trying to sell you spirituality. These very commercial televangelists that were trying to get your money, or at least he was trying to get money out of his audience members. So [where] that nexus of commercialism and spiritualism and the absurdity of that kind of official language that spanned both the commercial and the spiritual [influenced] some of the monologues in the film [which] kind of come out of that particular discursive territory.

I’m curious about the translation from the stage to the screen, and then implementing Platon’s voice into it as well. What was that creative process like? And how did you both weave in that narrative of death and dying?

NV: The theater show came out of another theater show that I did in Bankstown, which was just a segment of the show where it was me sitting on a hill top at nighttime just looking out into the sky, broadcasting to no one doing these monologues over a radio with a microphone. And so I took that and then I wrote a lot of other monologues, and then I had this series of monologues that I did as a theater show, and then I just basically sent the script of the three shows that I did to Platon. Platon combined the three shows, and [sequenced them] so that they make some sort of narrative. There wasn’t a logic to them in the first place, I think. Platon squeezed the best material out of all of them together, and left out some bits that I was like, “Oh, I thought that was pretty good.”

He needed something to give it weight to beyond just this string of absurd monologues, [then he added this framing]. Initially, I was a little bit circumspect about the addition of this extra narrative thread because my impulse was that the show was primarily about loneliness. And that was what the spine of the show should be. So this other thing of death, I was initially feeling like “Oh, maybe it’s something that’s not really necessary.” But then as it started to pick up a resonance for me I kind of understood [why it was there]. And it also comes from a real situation that Platon can maybe elaborate on later.

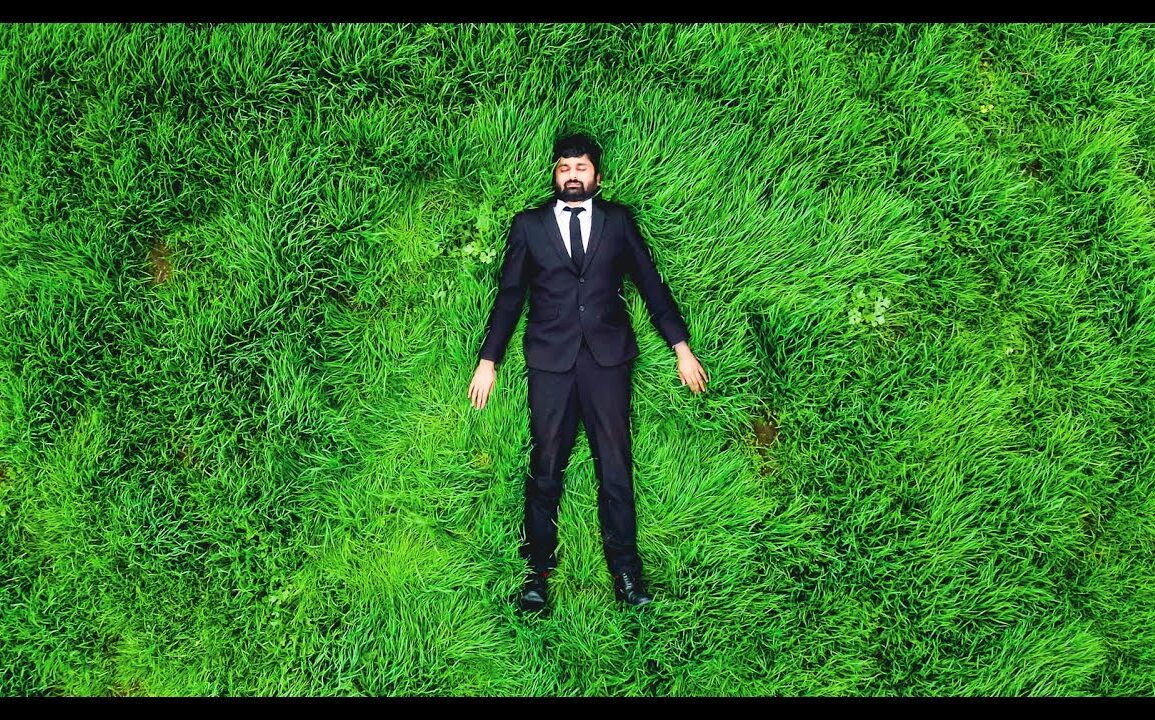

The film becomes about lifeforce essentially because this figure projects a manic and relentless energy into a microphone to be sent out into the ether, and to be heard by these people and projecting himself out through the microphone. You see all the scenes where he’s in these expansive, other world locations, and we can talk about whether they’re metaphorical or not. That’s the kind of thing that Platon and I jokingly argue about a lot, whether there’s any metaphor in the film and I kind of say “No, there’s no metaphor in the film. Everything’s exactly what it is.” But there is this idea of him projecting himself into other places. And so, the stuff in the hospital fits into that kind of imagistic territory or something. It’s that line of thought that leads the film to being about lifeforce.

PT: I mean, it’s an interesting idea, because early drafts that I did probably focus more on that loneliness aspect. Initially I was really taking it down a rom-com kind of path. It was really much more about the relationship between Sabrina and Neville and their as yet unrequited love. I was taking them on a road trip and incorporating this into the radio show. So it was very different.

But I got to the end of the second draft and parked it, because I just wanted to sit with it and let it gestate some more. That was in mid 2018, really. But then what, what subsequently happened was that a dear friend of mine passed away [Vanna Seang], who was the cinematographer for Alvin’s, very suddenly at 35. This was a really difficult time for me. I think I was in shock for maybe three months and then the grief didn’t hit me till a little bit later. It was just so unexpected. I was filming with Vanna in the week before he went to hospital and then two and a half weeks later, he was dead. I helped him home from the hospital but then he died a few days later, unexpectedly. It wasn’t supposed to happen that way.

I’d already parked the early draft of the screenplay but because I had been chatting to Vanna about shooting it – I just didn’t even think about it. And after he passed away, I couldn’t think about doing it without him. I had no energy to do anything. Thankfully working on Wine Lake the short film helped me focus on something else. I can thank Ailis Logan for that. I was still grieving. I actually moved to Japan for six months and threw myself into writing my new project. It was quite a difficult period.

And then, on the festival circuit for Wine Lake – at Raindance [Film Festival] in London, I just got inspired again, a little bit inspired. It was a year after his passing, and then I just kind of thought “I’m going to revisit it again.” I gave Nitin a call, “[Are you] still keen to kind of pursue this?” Nitin said “Yeah.” I said, “Let me have another stab at it.” But it just felt like it couldn’t just stay the same. I wasn’t the same person after losing Vanna.

And the weird thing is, and I only realised this in hindsight, in all my film work, which is my personal work, and in a lot of my early music videos too, a lot of the ideas come out of me dealing with some sort of trauma. A lot of the creative process is actually just me working through trauma and I feel like through this creative process I can come to terms or accept or understand stuff about the world and myself and life in general. That’s why I’m attracted to stories that are a little bit offbeat or absurd, because this allows me to kind of make sense of the whimsy of life and the fleetingness of life. That line is in the new film actually. How fleeting and ridiculous and combustible life is you know?

With Alvin’s it was me dealing with anxiety and an abusive father. It was me dealing with obsessive-compulsive thoughts and how these obsessive-compulsive thoughts can stain your sense of reality and become your reality. The menacing stains of black sludge permeating your apartment walls, which turn out to be sweet soy sauce – only to then discover that it is your own mind who is responsible for creating this reality. And in The Lonely Spirits Variety Hour, I had to kind of come to terms with the fleeting nature of life and the ridiculous nature of death. So I just kind of ran with it.

Revisiting the earlier drafts of The Lonely Spirits Variety Hour was really just me coming to terms with those seven stages of grief. It was a year after he passed, and I was making sense of what had happened. I’d also helped Vanna’s wife Krystal complete a documentary that he had shot but never finished. Vanna moved to Australia as a refugee from Cambodia, and had spent many years in a Thai refugee camp on the Thai border. Because he hadn’t heard that story, he took his parents back on a journey through Cambodia to this Thai refugee camp and asked them to just talk about how they escaped the Khmer Rouge, how they made it out safely. And it was a real personal experience, Vanna is in the doco asking all the questions.

I helped facilitate the post-production, because the film was only rushes at that stage. So I was in the middle of this process of helping Krystal complete it. I worked with an editor in Cambodia, we got all the 30 hours of footage translated, working through them to create the story. It’s called Return to K.I.D., if anyone wants to watch it they can find it on YouTube. And it’s a great story of survival and it’s Vanna’s story. After starting that process with Krystal I seemed to find space to come to terms with his loss.

Thank you for the honesty as well. I know that talking about these things is difficult.

PT: It is. And, the interesting thing is – today is Vanna’s birthday. I was reflecting on that yesterday, because we were shooting Alvin’s in the Kalgoorlie Salt Lake with him on his birthday, and some photos came up and I was at the table with my partner and I just broke down and I was crying. I still feel his loss. And it’s weird that we’re doing this interview on his birthday. And I was telling my partner about what happened on the first screening night at Revelation in Perth where we had that weird blackout in the cinema. And the panda came up [on screen] and the lady came in from the cinema and was really apologetic “It never happens”. And I just said to my partner, “I knew that Vanna was in that room doing that.” I was laughing to myself, I wanted to cry, but I could only cry yesterday telling him the story because I didn’t want to cry in front of the audience that night, in front of you guys at the cinema. But I just kind of felt Vanna in the room because Vanna was a prankster. Like without a doubt, Vanna would prank everyone. So I went “Oh, yeah, now he’s pranking us. He just wants to show us that he’s in this room, watching the film.” I’m not religious – maybe I’m a spiritual person.

That was really weird. Everyone turned on their mobile phone lights to shine light on us as guests in the cinema. And it took about five minutes for them to sort out the lighting and then that panda that came up, which was kind of out of Alvin’s.

NV: Also the way those two trajectories, the loneliness and then this idea of lifeforce come together in the film, why it then made sense for me was because this idea you project and send out your life, this energy throughout your life until the time that it expires, and you hope that along the way, somewhere, it connects with somebody and resonates. And that’s what the character is doing throughout the film, sending this energy up hoping that somebody until that energy then runs out.

PT: That sounds like a metaphor. [laughing]

Let’s lean into that then. Metaphor or not?

NV: Well, Platon put on the poster: ‘There are no dress rehearsals.’ I wanted the tag line to say ‘There are no metaphors in life.’ Just to kind of throw a spanner in the works. I always joke with Platon that there’s no metaphors in the film, I hate metaphor. I’m more from the kind of Plato’s Republic sort of approach about poetry and image making being bad for society. And I kind of lean into that.

Of course, joking. There is this great reference from this book by Leslie Jamison called Make It Scream, Make It Burn, and it’s this beautiful definition of metaphor as a salve for loneliness, that two terms take new resonance through companionship and it’s bringing two disparate things together, so that they share some new resonance. I just thought it’s a beautiful definition of metaphor and its link to loneliness. But Platon, what’s your opinion?

PT: I agree with you. I understand how you can just go with this idea that there’s no metaphor, that it’s all literal. And, in life, it’s all literal, right? Because you’re living it. It’s not a metaphor, it’s real feelings, and this is my present state, and this is what I’m going through. And that’s absolutely literal. So I can see how you’d want that interpretation. But sometimes a metaphor allows you to transcend that a little bit. And it does give you some objectivity, where you can remove yourself a little bit from the subjective.

NV: But I kind of take great joy in situations where you can’t quite resolve something into a metaphor. So I hope that’s the case with this film, where people are thinking, “Is this a metaphor? Or is it not, I can’t resolve it. And that’s frustrating to me.” I don’t know why I find that kind of productive territory between something not being a metaphor, and being a metaphor, and the thought of thinking through all of that, [why] that territory is interesting for me to inhabit when I’m making images or meaning writing stuff.

PT: Someone yesterday said to me, “Your films are a really lovely juxtaposition of intimacy and grandeur.” Perhaps that’s life and maybe the metaphor as well. The grandeur of metaphor and the intimacy of the subjective.

NV: From psychoanalytic stuff, not to get too much into that, but there’s this idea that metaphor is kind of comparable or of the same structure as condensation, which Freud and Lacan talk about as an unconscious process of mashing together two things or compressing disparate things into one kind of representational unit or package. Where that process goes awry or where it’s a difficult process of condensation when things don’t quite weave perfectly together, I think that’s the kind of metaphor that interests me more so than where the metaphor is kind ‘This means that’.

PT: I agree with you Nitin, because I think it’s open to interpretation. I don’t like it when it all just fits in easily. I like it when people need to interpret the work through their own life experiences, based on their own viewpoints, based on their own religion or ethical standards, their own perspectives and it will mean something different every time – every person will take away something different. Maybe that’s the difference between art house and commercial films. The art house film allows the viewer to interpret the material – commercial films don’t allow for that.’

NV: That goes back to the absurdity as well, this kind of image of Sisyphus pushing the rock up [the hill], but transposed into a person trying to fit a square peg into a round hole and even though it doesn’t work the first time you keep trying and trying. And so it’s kind of arrived at this final, nicely, woven together, sense of meaning, which can never arrive at really, and that’s kind of what the whole struggle that the main character has is pointing to that.

I want to touch on one of the main things which I love about this film, which is the Australiana and the presence of koalas and big animals and big things. Can you both talk about what that means to you creatively and to the film itself?

PT: Look, I love Australian-ness. It’s not often celebrated the way that I perceive it, and the way that I live it. I think a lot of our films have become vassals for American culture, and I don’t like that. So I’m always trying to find a way to slot some obscure or weird Aussie reference that perhaps only Australians might get or understand. And for me, a lot of ‘big things’ were about that, the grandeur of what it means to be Australian. You can often bring the stereotypical things into that, the Opera House, the Harbour Bridge, Uluru, the Great Barrier Reef, but there are all these other grand things in Australia which aren’t celebrated. And I was trying to weave that in so people understood that this is a quintessential Australian film. That it is set here. That it is part of the landscape and fabric of this country.

Every single prop detail is critical – I incorporated lot of Australiana because I love that stuff and so does my partner. It’s really fascinating and interesting. I think it says a lot about who we are as a country and we don’t see it enough. I kept laughing during the filming and edit because there’s a pillow in the back radio studio set in The Lonely Spirits Variety Hour that’s come from an old tea towel, ‘Australia 1988’, It’s got a horrible looking koala on it with red crazy eyes, but I strategically placed it in the back of the radio studio where it’s quite visible. There’s certainly a few koalas in this one and the some big things too – namely animals.

NV: Platon was saying how people in interviews ask him about “What’s this film saying about diversity and cultural heritage?” And I think the film largely avoids that. Other than to say that Platon, maybe I’m misrepresenting you, but often his answer to that is “I’d say nothing about it. I just make films with the people that I know that are in my life. And a lot of them happen to be people of colour.” But the only kind of reference to any of that stuff, if you wanted to perceive it, is in this character who’s from an Indian background, but he’s sitting surrounded and encompassed by this colonial Australian iconography really. There’s plates of Prince Charles and Diana there, and there’s all of that sort of stuff. That is there purely on an image level, then there is all kinds of different contexts whether it’s the philosophy or whether it’s the jazz music that are feeding into this character’s mind and what he’s projecting out into the microphone, that’s one of the elements that’s there as well, so you could read it like that.

I really want to touch briefly on Sabrina and the dance and the choreography for that. If you can touch on that and the use of the song too?

PT: Sabrina was part of the original stage play where she did a version of that dance – but it wasn’t used as a seduction scene in the play. When Sabrina came on board for the film, I had a long chat, and we spoke about how it was going to be used in the context of the film narrative and in the context of her relationship with Neville, the character, and so I gave Sabrina a lot of the parameters of how that would work. It needed to happen with a stool, in a very tiny space. About we needed to kind of go through this many – this is a bit of a spoiler – underwear changes. And Sabrina choreographed all that. She’s a clown doctor in real life, that’s her day job. She’s an amazing performer.

The music track was originally being used in the stage show. Then I went to see how I could license that particular track for film and thankfully, we got the license. I then found a great cover song for the soundtrack. It was about six to eight months worth of negotiating. It was really important that we got that track and I was thankful that we were able to use it.