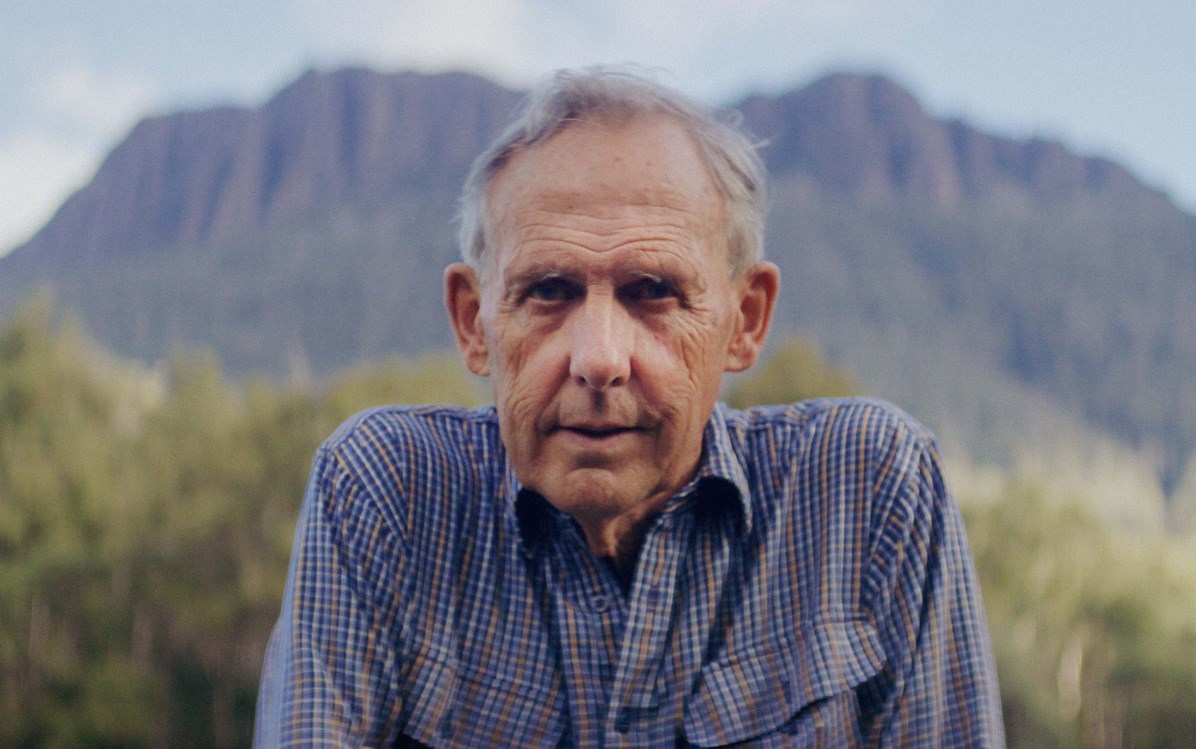

The symbiotic relationship between one man and the Tasmanian landscape is tenderly explored in Rachel Antony and Laurence Billiet’s expansive documentary The Giants. It’s a title that carries a dual meaning: the 6’3” man at the centre of its narrative, environmentalist Bob Brown, and the overwhelming stature of the gargantuan eucalypts of the Tarkine rainforest in Tasmania, some reaching the heights of over 100m. Both are giants in their own worlds, and as their continued existence stretches through time, communities and cultures are formed that in turn foster their own ecosystems and communities.

The Giants opens with an ever-escalating drone shot that carries from the forest floor to the breathtaking canopy of the Tarkine forest, briefly hampered by an intrusive computer-generated translation of nature that aims to reflect the manner that these trees ‘communicate’ with their environment. Throughout the film, this digital mimicry frequently interrupts Sherwin Akbarzadeh sumptuous and stunning cinematography. Akbarzadeh’s lens acts as a continuation of the transportive photography of Peter Dombrovskis – whose iconic photo of Rock Island Bend in the Tasmanian Franklin River helped change the tide of the Franklin River protest movement – and situates viewers in the pristine rainforests of Tasmania, immersing viewers in a world that demands protection.

Change doesn’t happen in isolation, with The Giants detailing how Bob Brown moved from a medical career as a doctor, to being motivated into action after the Tasmanian Governments removal of the national park status of Lake Pedder, which led to its subsequent destruction by damming. Continued acts of industrialisation of the Tasmanian environment was met with further protest movements, with Brown’s involvement inspiring swathes of people to congregate along the Franklin River and put their bodies on the line to stop a proposed dam taking place. Brown’s stature and affable presence looms in archival photos and footage, belying the genuine stress and anguish that Brown and many others were experiencing at the time. It’s Brown’s persistence, alongside fellow future politician Christine Milne and philanthropist Dick Smith, that helped secure the safety of the river and the surrounding rainforests as incoming Prime Minister Bob Hawke committed to protecting the landscape. The success of the Franklin River protests showed Brown that the only way to enact change is through political power, a mindset that ushered in the first green-focused party in the world, The Greens.

Antony and Billiet follow Brown’s life from childhood to now, exploring in depth the bond he had with his mother, his public voice about his homosexuality, and more, but they are also keenly aware that a rudimentary biopic form of storytelling would act in disservice to Brown’s legacy. Pulling direct influence from Dombrovskis pivotal photograph, Antony and Billiet frequently immerse viewers in the presence of nature, drawing emotion out of the green landscapes as Brown provides commentary of his life story. Instead of anthropomorphising the trees and their undergrowth, their story is told in a purely scientific manner, explaining with vivid realisation the manner that trees act as a sanctuary and adjust as an ecosystem. The longer we spend in the undergrowth and witness mushrooms emerging to break down leaf litter, or observing the canopy swaying in the wind, the more we realise that while Bob Brown is a figure that deserves respect and admiration, his role in their existence – which spans far longer than our mortal presence will ever experience – is almost akin to that of a custodian or protector. As trite as it may sound, these trees cannot speak for themselves, nature cannot stand as a figure in parliament and vote for its own safety and future, meaning it falls upon people like Bob Brown to act as their voice.

The impact of climate change and the need to halt environmental destruction is common knowledge, yet governments around the world still engage in destructive behaviour that has rates of deforestation increasing exponentially. As someone who writes from a ‘concerned citizen’ perspective, I carry a genuine fear that these kinds of films, as great as they are, may ultimately become archival documents of a world we once had, but lost. Even with a change of government, there has been precious little done to enact protocols to ensure that these irreplaceable forests and landscapes are secured not just for our own safety, but for the species that thrive within it.

In my region of the world, I am able to travel to forest locations like Margaret River and Yallingup, where my appreciation of the diversity of the wildlife in the region doesn’t come from canvassing how many kangaroos or owls I see in the habitat that skirts the road, but rather how much roadkill I drive past, often being picked apart by ravens or seagulls. On a recent drive to Esperance, I was able to take in the expansive vista of the aptly titled ‘Wheatbelt’ of Western Australia, a region that covers an overwhelming majority of the Southern corridor of the state. Along the 700km drive, the roadkill was minimal, a reality that came as no surprise given the region is dominated by heavily industrialised farmland. Looking at the impact of colonisation, it’s clear that this region has been harshly, and almost irreparably, altered due to extensive mining and farming practices. Some regions are so completely processed that the salt lingers in the soil, killing anything that attempts to take root. This is not nature. The push to turn Australia into a farm-laden, energy productive country is coming at the expense of the nature that makes this magnificent land the brilliant place that it is known as. Tourism Australia ads push lush, relaxing landscapes that invite international guests to luxuriate in nature, while close to these areas, bulldozers tear apart the landscape under the guidance of koala killing politicians.

There’s a moment early on in The Giants when Bob Brown becomes a vital part of the Tasmanian parliament. He walks into the chamber where the powerful minds confer, cajole, and criticise one another about the future of the region and he sees that the curtains are closed, blocking off the sunlight and the presence of nature from the very place where its fate is relegated to the history books in the name of progress. In this powerful moment, as Brown pulls open the curtains, he announces that nature is an integral part of politics, it is ultimately the most vital aspect of our lives. We cordon it off, obliterate it in the name of ‘more’, and proudly conquer it like we have conquered every other aspect of the world. Along that drive down to Esperance, I drove through a ‘biodiversity hotspot’, signposted with pride. Yet, all I saw was fields of nothing, accentuated by the occasional mining site. The more that we exclude nature from our lives, the more we take it for granted, and the more we actively allow it to be destroyed, removed, and relegated to history. We all have to open the curtains and let the sunlight and nature into our lives.

Bob Brown’s story is one that has been documented extensively in film and TV, with Kasimir Burgess’ powerful companion documentary, Franklin, exploring the Franklin River protest in detail, while also looking at the legacy of the many figures who stood on the frontline alongside Brown, including Oliver Cassidy who embarks upon the river, following in his father Mike Cassidy’s path. Additionally, there is no shortage of nature documentaries in the world that act as activist statements to inspire people to embrace cleaner living and be aware of the impacts of climate change. What stands The Giants apart from many of these eco-focused flicks is the manner that it reinforces the power of people standing up against change, like Queenslander Miranda Gibson who spent 449 days at the top of the Tyenna Forest treetops in Tasmania. Like Bob Brown, Miranda Gibson was one person putting themselves on the line in the name of change and protest, an act that ultimately paid off, with the 170,000 hectares of the region being secured as a world heritage site.

As The Giants considerately skews away from destructive imagery, it carries forward the mindset of what is taking place across all of Australia, positioning Bob Brown as an inspirational legend and asking the question of ‘who will follow in his footsteps’. Antony and Billiet bring forth a powerful documentary that should inspire as much as it moves, with James Henry’s symphonic score enriching the experience even more, ultimately leaving the impression that in a world of chaos and uncertainty, be a Bob Brown, and support the world we live in.

Directors: Rachel Antony, Laurence Billiet

Featuring: Bob Brown, Christine Milne