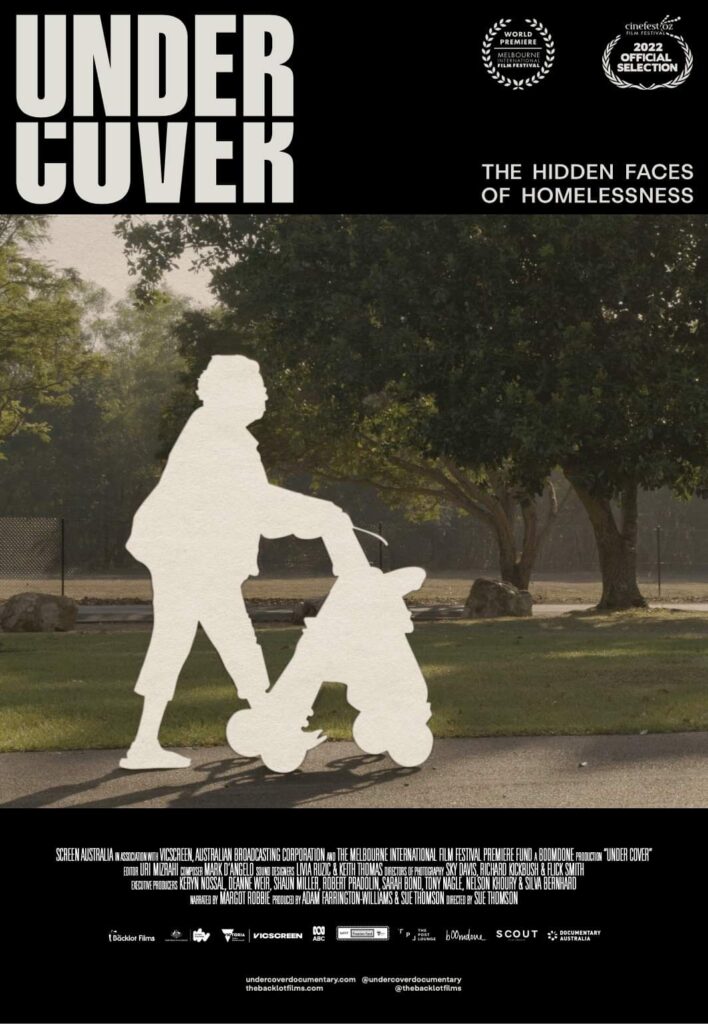

Australia is in the midst of a housing crisis, and within that crisis there are hundreds of thousands of homeless people, or people at risk of homelessness. Sue Thomson’s latest documentary, Under Cover, reveals the stories of some of the 240,000 women over 55 who are at risk of homelessness, with ten women sharing their lives. For many of these women, they have existed in silence, never having the chance to have their story shared with the world.

Sue’s filmmaking has always been deeply empathetic and compassionate, allowing her subjects to feel comfortable in the frame of the camera and share their lives as much as they feel they can. Under Cover is narrated by Margot Robbie and features Wirlomin Noongar author Claire G. Coleman alongside many other women who each share their vulnerabilities and hopefully inspire change in the community.

In this interview, ahead of Under Cover’s Melbourne International Film Festival and Cinefest Oz screenings, Sue talks about the journey to bringing this documentary to life, the difficulties of filming during COVID, and how she went about casting Margot Robbie.

For more information about Under Cover, visit the films website here.

It’s so nice to see that your films are still being really lovely and inclusive, and supportive of communities and different communities that maybe don’t get on screen as much as they should do. It was really nice to be able to watch Under Cover and get to know these people and see their stories [that will] hopefully help implement some change as well.

Sue Thomson: Thank you, Andrew, that sign that’s my whole modus operandi, really is to take stories from ordinary people out there in our communities that we don’t usually hear from or we don’t see on our screens. And it’s funny, I don’t even really think about that, because that’s all I want to do is tackle an issue that’s complicated and needs discussing in the world. But when I’m making it, I just think these people are all kind of amazing and extraordinary. It’s not til it’s finished, that I start to think to myself “Oh yeah, they’re not really famous.” To me, it’s Mary who lives around the corner or something, and you think, “Oh, my God, I’ve managed to get them up on screen.” So that is hugely empowering for them. And for me, I’m just enormously proud that I actually managed to pull it off.

When did you start shooting Under Cover?

ST: I started late 2019. I got an exemption from Screen Victoria to keep filming during the pandemic. But as you can imagine, with the women that are in this film, and trying to move around the country suddenly became extraordinarily complicated. As a documentary filmmaker, I say this all the time, the film that I kind of set out to make, I didn’t really make. The journey shifts and changes the story. But with COVID, this film was incredibly difficult to make, because I had to be so conscious of spreading the virus, if I was taking a camera person and the sound person to a woman to have a discussion, and they were nervous about me coming to them. It just added a really complex layer to the whole issue, of course, for them in their lives it was affecting them on a daily basis. I finished shooting, right – as I tend to do – during the Edit process, I was still doing little bits and pieces and pick-ups late last year. So we’ve really been editing this year. They’re always long these ones.

That’s the reality of documentary filmmaking and having a curveball like the pandemic thrown into the mix just makes it even more complicated. I think that Claire [G. Coleman] mentioned in the film that there was this almost equal level playing ground brought to those who are homeless and everybody else during the pandemic. I imagined that for you as a filmmaker for the story that you’re telling, there is a blessing and a curse about the pandemic in some capacity because it just helps reinforce how difficult and how hard life can be for those who are either on the brink of homelessness or experiencing homelessness. How did you manage to pivot on the go?

ST: When I was talking to her, and then she said that line that day about how something like a crisis or a pandemic is an equilibrium and a level playing field for all, I was really shocked because it was so true. And then how she said that if you had experienced homelessness, or anything close to homelessness, that when life throws you these terrible curveballs, and you’re struggling, that perhaps those people who have always struggled and had to survive, under very difficult circumstances actually do better than the people that have been comfortable and avoiding it and burying their heads in the sand, so to speak.

I think every single day of 2020/21 were complicated, as you know, we all know, and added a level of heartbreak to the film. But what was interesting for me as a filmmaker is every single person I spoke to, didn’t really want to cry. These women, as you might have noticed, they’re very proud. They’re not complainers. They rarely say “Woe is me.” They’re very resilient and resourceful. But I think underneath that sort of rod of steel, that strength, that special strength they have, these people are broken, and they just managed the pandemic as they did their entire lives. They were sad, [and] it kind of gave the whole film this sort of pall of sadness without actually having to say too much of it.

Under Cover is, to me, it hasn’t got highs and lows, it’s just people telling their story as it is. And as a filmmaker, I didn’t want to go in and alter that too much. Sometimes in the edit, you try and find ways of making someone’s story a little bit more interesting or entertaining, and in this film, I really worked hard. And I think that’s just comes from experience and trust in myself and my skills [to say], “Let it go, this is what it was. Don’t try and make it something else. Don’t try and titillate your audience because you’re concerned that the story doesn’t have hysterical laughter or people sobbing.” And I really am proud of the fact that the film is very melancholy, but I’m not trying to make you cry, which sometimes in the edit it’s what you do. And so getting back to your question, what I’m saying is, I think the pandemic has added just sort of a veil over the whole thing that these women were dealing with this quietly out there in the world. While we’re all dealing with it, they’re dealing with it and it’s just doubling up on their complications of everyday life.

While this is very emotional, it’s also never overbearing, it never guilts viewers. And I think one of the things that is really quite important for viewers to realise as well, is that there is an emotion to this particular film that people who are experiencing homelessness [is that] they’re not sitting there crying every single day. They’re just trying to get through the day and trying to survive and be able to get somewhere safe and exist.

ST: I really thought I was going to be talking to hollow women, because women are seen as emotional creatures. I’m an emotional person. Often in interviews, I would cry while we were talking, but that was just a moment for me that happened or I was feeling emotional. Maybe in a way, life has battered them around enough for them to not cry at everything that happens in their life anymore.

And I think that that’s the thing is that you’re providing people have perspective, which we may not really think about all that often, and that’s really very important. It seems almost fortuitous as well that I’m talking to you today when the Albanese Government is going to be submitting their paid leave domestic violence bill to Parliament today. It feels very resonant where there are a lot of people who are victims of domestic violence who end up being homeless. How important was it to be able to tell those stories in a modern Australian context for you?

ST: I sort of just touched on domestic violence, because I felt that to go deep into that, then I was probably going to be making a different film. There’s two women that talk about it, but we didn’t want to name names of people, it wasn’t that sort of film. It was like their experiences and what has led them to where they are today when they’re in the film. And we would talk about that off camera, and whether people wanted to say more about it or less. In the end, this film was more about a whole multitude of experiences and complexities that come to that. [With] domestic violence, nearly 70% of women that seek out short term accommodation are running from a violent home situation.

Again, I feel like whole film is quite a political film, and everything is there for the taking. It’s whether the audience are hearing it and picking it up. And I think they will. [With] domestic violence, the shocking statistics in this country, in a western rich country, is absolutely terrifying. And I think every single day, there are women out there being abused by men, and if Under Cover can help save one person’s life, then I’ve done my job.

And Albanese is doing that today, I mean, it saddens me Andrew that that even has to happen. I struggle with the whole notion that we have to pass a bill in Parliament, it’s like, what the fuck happened to this world. But, great, and thank God we have this government now in place, and maybe there will be a roll on effect and women will feel safer in a relationship.

Fingers crossed. Let’s talk about the narration from Margot Robbie. I don’t know if this was a conscious decision or not when you were casting her to do the narration, but I found that this is a film that pairs very well with the Big Short, which she features in, and that’s talking about the housing crisis that is impacting the whole entire world.

ST: Exactly the film that I talked about in 2019 when I started making this documentary. I love The Big Short.

Did you had that conversation with her when you were going about organising her?

ST: You know what, we never did. And it’s funny because I was making a film about women of an age and housing crisis, they’re sort of, in a way, kind of heavy topics. To get an audience to see a film like this is hard. I’m lucky with MIFF which is fantastic. And, the hour version will be on the ABC. I feel incredibly lucky and proud that the film will have an audience at all.

But I knew that to get it even further, and to get it over the line, I needed someone to bring an audience to it, that’s our thing about big name narrators, you think about Naomi [Watts] and Nicole [Kidman] and Rachel Griffiths. But I came to Margot quite quickly, within hours of thinking about this early on. We had time during the lockdown where I would be stuck at home and I started writing to Margot Robbie agents, thinking, “Okay, if I could go for the sort of woman could narrate dry bits of information in this film, who would it be?” She’s so colourful and so sexy and so seemingly grounded, I don’t know her personally, but then I did a bit of research on her and she’s the ambassador for a very grassroots mother and daughter surfing club in Brisbane, and I just thought “She’s incredible.” And of course her feminist film history.

And so I started writing to her agents, and then of course, initially it was like, “It’s Margot Robbie, you’ve got to be out of your mind.” And then slowly but surely over nearly two years, he said he was sending her films that we’ve made, and we never knew if that was true, and then there one email saying “Margot’s interested”. This potentially is real and it might happen.

But she felt to me [right], and I wanted my daughters to want to go and see this film. And I know that with the plethora of stuff that is on streaming services, it’s hard to get anyone, let alone young people, to go and see a film and let alone documentary about older women. Having Margot suddenly, people like my 26-year-old and my 24-year-old go, “Wow. She’s a queen that Margot.” And I’m delighted that she may bring a youthful audience to Under Cover.

While it appears on the surface [like this] might only really be affecting a group of people who the audience might not ever be part of, it actually impacts everybody. And that’s one of the things which I kept thinking about as I was watching, that that could be my mum. And obviously, we shouldn’t always look at things in the capacity of “This could be my mum, it could be my sister, it could be my daughter”, but on the same hand, there needs to be some kind of community action, community awareness of things that can be done. And I think that this film certainly does that. What do you hope that audiences will be able to take away from this film? What kind of action do you have that they’ll be able to implement in their day to day lives?

ST: I think what you said about the fact that we don’t want to dwell on things on the negative in our lives too much. While I’ve been making Under Cover, so few people actually acknowledge it, “I didn’t realise that. I didn’t know that an older woman living in her flat somewhere whose husband may have died, or she doesn’t have a partner, could potentially be struggling financially.” The reason we do this is to start conversations, and then hope there’ll be some sort of action or change.

We have actually got an impact campaign attached to Under Cover, which I’ve always tried to do with my films. I’ve done it by myself or with my producers. This one we actually have built in and we’re going to every capital city, and we’re having impact screenings. And were trying to get people working in the sector and policy makers and people who can potentially change policy, and we are trying to start the conversation and get it into schools. And that actually is happening with Under Cover. Whereas with other films I’ve tried to but it’s bloody complicated to keep it going. We have an incredible impact producer, Diana Fisk, on board. After the screenings at MIFF we’re having a Q&A with a few of us.

Even talking about Claire G. Coleman and the women in the film, they are talking about it now to their friends, and they were all quite secretive initially. And I think it’s given them confidence to say, “This is a number you can call if you’re struggling,” or “These are some organisations you can reach out to,” or “If you hear about someone that is struggling to pay their rent or their mortgage you can talk about it openly. It’s not a shame.” I think there’s no doubt that’s already happening with Under Cover.

Claire G. Coleman is incredible. I got Claire in the film, because I knew from research that she had seven years of homelessness, now she’s becoming a superstar. She’s extraordinary, she’s powerful, she’s everywhere. And she has a lot to say about it. And if I think between all of us we will help affect a small amount of change in the world.

Margaret, who is in the film, she lives in a van, she’s coming down to the opening. This film has changed her life already. I found her on a Facebook site for women who are living in their cars and drive around Australia, she just texted me the other day, because she’s coming down for one night to say this screening, “I can’t tell you how much this has changed my life already for the better, just being open about my experiences, rather than always pretending my life is different.”

I think when you when you let go of shame, and it becomes your story of change, it’s really an empowering thing. I’ve been seeing it with all the women. It’s the like The Coming Back Out Ball, it’s a very similar thing that you can claim your history instead of pretending it never happened. It’s okay. “Yes, this happened to me. And maybe it wasn’t great. But I’m now one of the people who can have a small impact in changing the way Australians think about older women who are living on the poverty line.”

What does being an Australian filmmaker mean to you and what does it means to be working and telling these kinds of stories in Australia today?

ST: As a woman over 50 myself, that’s why Under Cover resonates because I made this film because it could have been me. It’s the first time I’ve made a film about a topic that’s very close to my heart. I made a film about mental health, and I’ve had my own problems of anxiety. This could have been me in this film.

I am Australian, I want to tell Australian stories because we are such a young and beautiful country, we’re still forming and creating our own culture. And I’m proud to be a part of that. I love the fact that in 2022, we seem to be embracing our First Nations [people], and I will do anything to be a part of that and share knowledge. And to watch the world change and to see the Aboriginal flag go up on Sydney Harbour Bridge, and to drive across the west gate and see the Aboriginal flag, it’s about fucking time. And I’m really excited to be a part of that change. And also to just watch it from the sidelines. I’m so glad I’m alive as these things happen, finally.

To be a filmmaker is all I ever wanted to do, and I feel very lucky that I’m achieving a small amount of success in getting films made and as you would know Andrew, it’s a really hard thing to do. I’m really, really proud to be an Australian making Australian content.