With over 170 Australian features, documentaries, and short films released theatrically, on streaming platforms, and at festivals during 2022, it’s safe to say that the Aussie film industry is shrugging off the post-pandemic blues in a mightily productive manner. The creative results of Hollywood setting up shop down under to escape COVID emerged out of isolation with Baz Luhrmann’s Gold Coast shot Elvis, George Miller’s Sydney-sided Three Thousand Years of Longing, and AACTA-certified trailblazer Chris Hemsworth sticking close to home and family with Joseph Kosinski’s Spiderhead (Queensland) and Taika Waititi’s Thor: Love and Thunder (NSW) all making Australia look as un-Australian as possible.

Out of the shadow of money-rich studios, Aussie indie filmmakers equally thrived with a wealth of creativity and ingenuity that has you wishing that the Federal Government would support the industry more than it already does. Glenn Triggs (mostly) dialogue free Dreams of Paper & Ink told a decade spanning love story with moments of genuine passion, while Sari Braithwaite’s tender Because We Have Each Other brought us into the home of a unique Aussie family, and Catherine Hill presented a day-in-the-life of a homeless woman in the considered Some Happy Day. These are just a handful of independent films that worked hard to tell Australian stories and keep Aussie voices on screen.

Before I jump in with my favourite Australian films of 2022, a few notes about the list itself. Out of the films released, I watched 101 Australian features, documentaries, and short films. The below list is the result of a wealth of difficult decisions of which films to include and which films I had to leave off, all of which shows that 2022 was a great year for Australian cinema.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers readers are advised that the following article contains images and names of people who have died.

Once you’ve gone through the 2022 list, check out the 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, and 2016 lists.

Mob stories are a dime a dozen, so when something neat and entertaining plays around with the format, it’s worthwhile taking notice. Such is the case for co-writers Riley Sugars and Chloe Graham’s darkly comedic Hatchback. Sugars takes directing duties, immediately situating himself as a filmmaker on the rise to keep an eye on, harnessing the acting brilliance of Stephen Curry and Jackson Tozer to tell an affable tale of a mob cleaner Vince (Curry) who enlists his less-than-bright brother-in-law Ted (Tozer) to help dispose of a body. Things immediately go awry when instead of nicking a van, Ted steals a hatchback, causing an escalating series of comedic exploits from trying to fit the rapidly stiffening corpse into the boot of the car, to one of the best tomato sauce gags in a long while. Hatchback delights with the push-pull relationship between Vince and Ted, two mismatched fools in a situation that simply cannot end well. I cannot wait to see where Sugars, Graham, and Tozer go from here.

There were two outrageously expressive music-focused films that struck a chord with me in 2022: Baz Luhrmann’s epic Elvis overwhelms the senses as Austin Butler gives a transformative turn as Elvis that shoots shivers down your spine with the way he becomes possessed by the spirit of the King, and Seriously Red, Gracie Otto and Krew Boylan’s ode to Dolly Parton, believing in your true identity, and even the King himself (at least Rose Byrne’s version of Elvis that is). Luhrmann’s Elvis is as Baz Luhrmann as a Baz Luhrmann film can get, with frenetic editing, electric shots, and dizzying sound design that leaves you feeling like you’ve just eaten all of the fairy floss at the Royal Show. Naturally, with Hollywood funding behind it, Elvis has the edge on Seriously Red, but both carry a level of affection and adoration for their chosen music icons that is undeniable. Equally so, Elvis is an immediate classic, securing a swag of AACTA awards that remind just how Australian this deeply American story is, and while Seriously Red was not exactly critically embraced, it carried an emotional authenticity that resonated powerfully with me, and really, isn’t that all that we want from the films that we dedicate our lives to watching?

Read Andrew’s interview with Lachlan Pendragon here

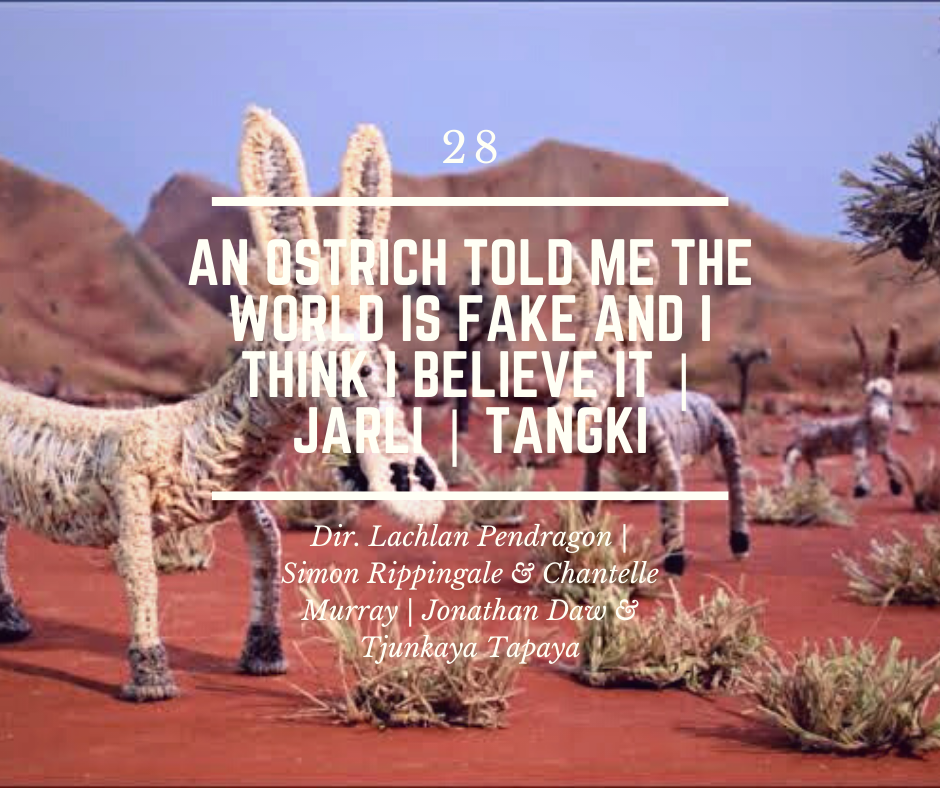

The creativity that exists within these three stellar short films highlights a new wave of Australian animators on the rise. Lachlan Pendragon crafted the existential stop-motion animated comedy An Ostrich Told Me the World is Fake and I Think I Believe It by himself during COVID lockdown, harnessing a delightfully meta narrative about an office worker realising he’s being manipulated by a greater figure and turning it into an award winning success (Lachlan won the Gold medal at the Student Academy Awards). Chantelle Murray and Simon Rippingale’s aspirational and joyous short Jarli showcased the story an Aboriginal girl (vibrantly voiced by Madeleine Madden) who dreams of flying into space (a journey which the film was able to achieve in 2022) with a delightfully Australian visual style that left me yearning for a feature length film with this look. And then there’s Tjunkaya Tapaya and Jonathan Daw’s heart-warming animated short Tangki (Donkey) that utilises the work of the Tjanpi Desert Weavers to retell the story of how donkeys were introduced to the desert community of Pukatja (Ernabella), and the relationship that the Anangu people have with the tangkis, leading to a visually unique and expressive style of animation that leaves you feeling like you’re sitting in the desert with the community and seeing the story being retold in front of you. Each of these shorts challenged the notions of what traditional animation could be, and in doing so showcased the possibility of creativity and imagination going forward.

Across his career, legendary cinematographer Rick Rifici has helped define our relationship with the water through his ability to immerse audiences in environmental situations that seem almost impossible to capture. With Facing Monsters, alongside director Bentley Dean, Rifici pushes the realm of surfing cinematography to the next level as they detail big wave surfer Kerby Brown’s exploits in the ocean, throwing his body (and life) on the line as he tackles some of Western Australia’s most overwhelming and dangerous slab waves – a thick wave that moves quickly at a low height, breaking on reefs from deep water. Paired with Brown’s personal journey with mental health, Rifici’s cinematography stuns the senses, amplifying Facing Monsters into a truly powerful experience that has had Western Australian cinema-going audiences turn out in droves throughout the year to witness the doco on the big screen at Luna Leederville.

Read Nadine’s review of The Lost City of Melbourne here

It takes a considerate eye to look at the destruction of a city over the decades and craft a film that carries a level of awe and wonder for the culture that lingers in the rubble of gentrification and modernity. This is what director Gus Berger has managed to do with his expansive historical documentary The Lost City of Melbourne. Utilising the Melbourne lockdowns to take a journey through the Victorian history books, Berger witnessed a city that is at threat of losing its cultural identity and crafted a film that calls for an end to the gaping maw of the kind of homogenised destruction that has swept through cities around the globe. Berger reflects on what makes Melbourne unique, and in doing so shines a light on the structural ghosts that once dominated the cities skyline, highlighting the importance of communal venues like cinemas and theatres. When paired with the equally important Splice Here: A Projected Odyssey from fellow Melbournian Rob Murphy, The Lost City of Melbourne helps remind audiences what we stand to lose as we race into a future that prioritises rapid infrastructure progression over fortifying cultural identities and institutions.

Read Andrew’s interview with Tim Baretto here

Within Tim Baretto’s sun-kissed summer tale Bassendream there is a wonderful feeling of reclaiming the positivity of nostalgia from the manner that it has been weaponised by certain fan groups around the world. Now, that’s not to suggest that Bassendream is a pop culture focused affair, in fact it’s quite the opposite of that. Instead, this is a grand ode to Australian suburbia, to the ‘dry heat’ of West Aussie summers, to the winding down of the school year and the possibility of adventures over the holiday break. It’s a film about the cusp of new friendships and the unexpected dissolution of hard-earned bonds, to mucking around with mates and pissing off old folks with shenanigans. It’s the sound of hearing Paul Kelly’s Dumb Things for the first time and thinking ‘fuck, this song gets me’. It’s the anger at a sibling for tearing apart your prized basketball collectors’ card. Baretto’s film is an experiential one, gleaned from his mind like something that only the outer-suburbs kids can do. Bassendream was shot on film, evoking both the pastels of nineties attire, almost appearing at times like the faded curtains that daylight savings alarmists ranted and raved about in the letter’s column of The West Australian newspaper. There’s a reason why there was a tangible electricity in the air after the sell-out screenings at Perth’s Revelation Film Festival and it’s because a unique slice of Australiana was captured on screen with love, dedication, and authenticity in a manner that has never been captured before.

Read Andrew’s interview with Jane Castle here

The art of reflecting on the past with awareness of its impact on the present is a difficult thing to master, but filmmaker Jane Castle managed to do exactly that with her familial documentary When the Camera Stopped Rolling. Initially conceived as an intellectual film about death, When the Camera Stopped Rolling evolved over almost ten years of production into being a reassertion of Jane’s mother, Lilias Fraser, into the history books of Australian cinema. Brilliantly autobiographical and revealing, When the Camera Stopped Rolling is at times a difficult watch as Jane works through her relationship with her mother through pristinely presented archival footage (which occasionally plays like a silent film) with a level of vulnerability that gives way to an emotionally enriching experience come its close. Ultimately, When the Camera Stopped Rolling showcases a labour of love for parents and the culture that they introduce their children to, while also recognising the struggles that emerge from a crumbling mind.

There’s a deliberately ethereal quality to Maya Newell’s latest documentary The Dreamlife of Georgie Stone that elevates the story of transgender rights activist Georgie Stone. The Dreamlife of Georgie Stone is framed around Georgie’s fight against the Family Court to allow transgender kids to begin hormone therapy, alongside the support Georgie’s family gives her during her own transition journey. It’s in the telling of these two stories we see the emergence of an activist, an icon, an emerging leader, and an actress. Maya Newell’s films celebrate the importance of identity and reinforce the need for community and familial support to allow those identities to flourish. Her work is always collaborative, acting as a facilitator to help share her subject’s stories with the world, a point which is amplified by the abundance of home video footage of Georgie growing up with the support of her father. This is an all-embracing documentary, one that makes you grateful that there are selfless people like Georgie Stone in the world fighting for those who may not be able to fight for themselves.

Penelope McDonald’s delightful and devastating documentary Audrey Napanangka was filmed over ten years, telling the heart-warming story of Warlpiri woman, Audrey, her Sicilian partner Santo, and her foster family as they live life in Mparntwe (Alice Springs). The family aspect continues off screen, with Penelope’s son Dylan River assisting with lensing duties, giving the documentary a communal, all-embracing feeling that leaves you grateful for the experience of spending a decade with Audrey’s family. While there are moments of tragedy, Audrey Napanangka shows that time spent with Audrey’s generosity is a great privilege, ultimately reminding that the complexity of life is what makes it worth living, especially when surrounded by people you love.

William Duan’s precise and precious short Tuī Ná tells the story of David (Yipeng Xu), a 17-year-old Chinese boy discovering his queer identity amidst his dedication to his mother and work. Immaculately shot and framed, Tuī Ná aches with yearning for a sense of place in the world. This feeling is paired with David’s burning desire to embrace the body of another man who also craves his body. Christine Cheung edits each motif together in a delicate and tender manner that shows ultimate compassion and consideration for the complexity of the story that Duan is showing here. Intertwined with shots of flowers and David look straight into the camera are moments of David and his mother leaving offerings and prayers for David’s grandmother who has recently passed. At the close of Tuī Ná, I just wanted to give David (and by extension, William) a hug.

Australia’s finest modern documentarian Eddie Martin had a stellar 2022 with two brilliant documentaries being released: Fire Front and We Were Once Kids. While Fire Front emotionally wrecks you in a way you might expect a bushfire documentary to do, it’s within We Were Once Kids that shows why Martin is one of the very best at this kind of reflective exploration documentary. Here, Martin explores the making of Larry Clark’s controversial nineties cult hit Kids, with interview footage of surviving cast members like Hamilton Harris (who shares a co-writing credit with Martin here) being interspliced with archival footage of Harold Hunter and Justin Pierce who talk about their time making the film. Revealing and eye-opening, We Were Once Kids is about reflecting on the decisions we make in our younger years and how time changes our perception of what is right and wrong. Martin directs with utmost empathy and understanding for the films subjects, ensuring that this is not just a film for those curious about the making of Kids.

At the centre of Ben Lawrence’s Ithaka is a person who we barely see on screen at all: Julian Assange. Yet, as Ben said in my interview with him in 2021, “it’s not a campaign film. It’s a film about a campaign.” And it’s within that notion, the story of the people behind the campaign to free Julian Assange, that Ithaka explores the lengths that a father will go to be reunited with his son and a wife with her husband. Yes, Ithaka is about the freedom of the press, especially in the shadow of Trump’s presidency, but it’s also about one of the most complex and draining political and legal struggles that modern society has seen. Lawrence never frames Ithaka as a thriller or exclusively about the politics at play – even though the story suggests that’s how it should be told – instead, he leans into the humanity of the piece, allowing John Shipton (Julian’s father) to stand tall as a dedicated advocate for free speech and for his son’s mental health and safety. Compelling and captivating, Ithaka is ultimately about a complicated family that is just trying to clear a path through a myriad of legal woes to be reunited, making for important and impressive viewing.

The expanse of the outback is brilliantly realised in Goa-Gunggari-Wakka Wakka Murri woman Leah Purcell’s feature film debut The Drover’s Wife: The Legend of Molly Johnson. Purcell is a triple threat here adapting her own book and play, directing, and taking the lead role of Molly Johnson, overlaying her singular vision against the Western genre and giving a well-deserved feminist and First Nations stance. The use of real landscapes amplifies the drama to a surprisingly emotional effect, especially in a moment when Rob Collins’ Yakada teaches Malachi Dower-Roberts’ Danny the ways of the land as they sit surrounded by the twisted limbs of ghost gum trees. But it’s Purcell’s central performance that captivates the most, leading to a well deserved Best Actress win at the 2022 AACTA awards. It’s been two decades since Purcell directed her great documentary Black Chicks Talking, and with both The Drover’s Wife and Here Out West under her belt for 2022, we can only hope that it’s not another decade before we see her behind the camera again.

Read Andrew’s interview with Jayden here

Jayden Rathsam Hüa manages to turn the rather innocuous phrase ‘yummy yummy sushi time’ into an incantation that summons a genuinely unhinged short film called Sushi Noh out of the ground. Comfortably the best Australian horror film of 2022, Sushi Noh is a shlocky, grotesque experience that tells the story of a young girl (Geneva Phan) who becomes increasingly concerned about the ratcheting mania of her uncle (Felino Dolloso) who she lives with. Violently absurd, Sushi Noh contains enough wailing bloody mayhem to make you reconsider that supermarket sushi roll for lunch, all the while making you note the name Jayden Rathsam Hüa as someone to keep an eye on.

There’s a distinct pleasure that washes over you as you experience a piece of filmmaking that pushes against the boundaries of the form of storytelling it is working within. Juanita Nielsen NOW is one such film that engaged completely with my emotions, leaving me stunned and shaken by the sheer force of its narrative. Pulling from her experimental video installation, director Zanny Begg looks back at the 45-year-old unsolved murder of journalist and activist Juanita Nielsen and reflects on how the same fight that Juanita engaged in in the seventies is still taking place today. The impact of gentrification and unaffordable housing is explored through a historical and modern context, with the words used to describe the issues overlapping at times. The pinnacle moment of brilliance in Juanita Nielsen NOW! is when Begg plays out some of the variations of how Juanita might have died with actresses and performers embodying Juanita walking into the fateful Carousel Club venue in Kings Cross, often in unison. Juanita Nielsen NOW!

The Plains is director David Easteal’s three-hour docu-drama that follows his friend and colleague Andrew (Andrew Rakowski) as he drives home at five pm in congested Melbourne traffic. With the camera firmly placed in the back passenger seat, we sit with Andrew as he listens to the radio, navigates traffic, talks with his wife over the phone, and occasionally acts as a lift home for his colleague David (Easteal). This is a fascinating and mundane experience, rudimentary while it engages in profound acts of soul searching. I can safely say that there has not been anything like The Plains in the history of Australian cinema, and one can only hope that Easteal continues crafting films like this going forward. Considering The Plains in the age of Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du commerce, 1090 Bruxelles being crowned the ‘Best Film of All Time’ means that there’s every chance that while The Plains sits at position 15 on this list that it will only rise in estimation as the years roll on.

From Jane Castle’s When the Camera Stopped Rolling to Tom Zubrycki and John Hughes Senses of Cinema and Penelope McDonald’s Audrey Napanangka, 2022 saw a wealth of Australian documentaries that pulled back the curtain on the untold and under-celebrated history of Australian cinema. The most timely and essential documentary of the bunch was Alec Morgan and Tiriki Onus’ Ablaze, an empowering journey through Bill Onus’ (Tiriki’s grandfather) legacy as an artist, an activist, and a pioneer of Indigenous filmmaking. Ablaze not only details the work that Bill did as a filmmaker, but it meticulously explores pivotal events that impacted Bill, his friends and family, including the horrifying atomic bomb tests near Maralinga, Western Australia. This is a comprehensive conversation between grandson and grandfather, and we are privileged to be able to listen in on it.

It may be hard for people who live outside NSW to fully comprehend just how multicultural and (yes, here come the ‘d’ word) diverse Western Sydney is, but the anthology film Here Out West does an excellent job of presenting a part of Australia that has so often only been presented in satirical or poverty-porn terms. Here Out West heralds a wealth of multicultural voices from within the communities that are represented on screen, both on and behind the screen, giving an authenticity to the stories being told. A throughline of a baby being stolen from a hospital links each narrative together, with car park attendants, nurses, restaurant owners, rising entrepreneurs, mothers, daughters, fathers, and sons, all helping realise the grounded reality of Western Sydney. At its close, Here Out West leaves you wishing you could spend more time with each narrative and character, a feeling that I hope translates into more anthologies like this, or ideally, more creative opportunities for the writers (Nisrine Amine, Matias Bolla, Arka Das, Bina Bhattacharya, Dee Dogan, Tien Tran, Vonne Patiag, Claire Cao) and actors.

Franklin is Kasimir Burgess’ most accomplished work to date, acting as an all-encompassing journey that follows Oliver Cassidy as he canoes along the mighty Franklin River, following in the path of his father Mike Cassidy who decades ago fought alongside protesting icons Bob Brown and Uncle Jim Everett to save the Tasmanian landscape from irreversible destruction. Transportive visuals from Benjamin Bryan’s cinematography plays in unison alongside a wealth of archival footage that amplifies just how precious and delicate this ecosystem is. Luke Altmann’s score harmonises alongside these visuals, often presenting Oliver as a sole figure floating along the river, swallowed whole by a nature that aspects of humanity so eagerly wishes to conquer. Where Ben Lawrence’s Ithaka eschews the activist formula of documentary filmmaking, Burgess’ film eagerly wades into the water with its subjects, and in turn becomes a grander statement for action against climate change than many films that directly address that issue ever could.

Read Andrew’s interview with Simon here

Simon Target’s warrawong… the windy place on the hill operates on the same kind of wavelength of slow cinema that The Plains does, but instead of the unceasing bitumen of the city we’re presented with the stretching farmland of the remote town of Tooraweenah in NSW. Target follows Sue and Brian, a couple in their seventies facing the impacts of isolation, loss, and the emotional toll of downsizing a farm in a town with an ageing population. From shots of Brian rounding up livestock, to drone footage of the oncoming grey clouds and the wind that blows 24 hours a day, Simon immerses viewers in the day-to-day life of a farm. Time becomes obsolete and days lose their meaning as Sue and Brian become one with the land, dealing with a plague of mice by feeding their dead bodies to the voracious magpie family that lives on the farm. Sue and Brian are 60km from their nearest neighbour, 150km from a doctor, making the two-metre separation rule of COVID times almost feel like a farce, but it’s their reality. I think about the films on this list a lot, but it’s warrawong… the windy side of the hill that I come back to the most with the one-sided mirror of a cinema amplifying that distance between Sue and Brian and the world they live within. I often wonder how they are both going. I hope they’re ok.

Watch Not Dark Yet here

Bonnie Moir’s devastating short film Not Dark Yet hits like a fucking sledgehammer. An elderly man, Russell (Richard Moir, Bonnie’s father), lives in an aged care facility. His son, Luke (Nicholas Denton), is on the cusp of becoming his adult self. Russell relies on Luke to be his tether to the world outside the dark catacomb of the facility he is housed in, an while Luke clearly loves his father, the possibilities of the world await him. Not Dark Yet feels so intimate and familiar that it often feels like a mirror being held up to the audience. Moments of playfulness between Russell and Luke highlight the tender, joyous bond that the two share, showing that Luke’s decision to leave Russell abruptly isn’t one made of malice or frustration at his fathers ailing body. Richard’s performance will break your heart, while Bonnie’s direction will leave you in awe. Not Dark Yet is a sign of an important director on the rise.

Goran Stolevski’s confident and assured debut You Won’t Be Alone plays with the sub-genre of folk horror and pushes through its thematic overcoat of trauma to triumphantly announce itself as a stunning examination of life, living, and the harsh reality of the human condition. Cruelly shunned by local audiences and the AACTAs, You Won’t Be Alone stands as a rare Australian film that has received widespread international acclaim. Arguably, these same audiences may be unaware that it is, in fact, an Australian film, but that aspect doesn’t matter when the anthology-like narratives feel so universal. To break down this film in a short paragraph is to do it an injustice, so trust me when I say that this is a film that’s best embraced with knowing as little as possible. Just know that it’s like someone put Terence Malick in a teleport device with the All the Haunts Be Ours: A Compendium of Folk Horror box set and the melded product on the other end was this film.

Sara Kern’s debut feature Moja Vesna is a family drama wrapped around an engaging and powerful central performance from newcomer Loti Kovačič as Moja who gives one of the most powerful and soul-wrenching turns by a young actor in recent years. 10-year-old Moja has become the surrogate parental figure to her morose sister Vesna (Mackenzie Mazur) after the death of their mother. Equally adrift is their father Miloš (Gregor Baković) who manages to feed and house Moja and Vesna but finds it hard to navigate the additional impending life change that is awaiting the immigrant family: Vesna’s late-stage pregnancy that she almost entirely ignores the notion of occurring. Kern throws Claudia Karvan’s empathetic stranger Miranda and her whirlwind daughter Danger (Flora Feldman) into the mix to bring a welcome aspect of levity to the sombre situation. Australian films are often criticised for being too bleak or depressing, and while Moja Vesna does fit that brief, when it’s as confidently and empathetically made as Sara Kern’s film is, then who cares? May she craft a library of films that crumbles my soul like Moja Vesna does if she so desires.

Of all the films on this list, Anonymous Club is the one I’ve revisited the most, having logged it five times on Letterboxd, with one entry stating “This film has become part of me. I can’t separate myself from it.” While I love this film completely, it is a film built for the Courtney Barnett faithfuls of the world, with director Danny Cohen eschewing the traditional music documentary narrative and relinquishing the history of its subject in service of giving Barnett a Dictaphone and asking her to follow her own album title: Tell Me How You Really Feel. Heading out to tour that album, Barnett is open and vulnerable with the Dictaphone in a way that an ‘interview to the camera’ style doc may have struggled to gather. Barnett’s music reflects her own anxieties and mental health, making her Dictaphone entries to Danny feel like supporting evidence to her mental state. Being open about mental illness is difficult, and for Barnett it’s even more complex when that openness takes place in front of a room full of strangers. Anonymous Club was shot on film, giving it a similar warm, ephemeral feeling as to what you might experience at a live concert. Again, this film is unlikely to convert folks unfamiliar with Barnett’s music to her cause, but for the CB faithfuls, this is a comfort watch, a warm embrace, a rare connection in the audience with a stranger across the room as you both sing in unison, tears running down your face, the lyrics to Sunday Roast.

Great Australian comedies feel like rarities amidst an array of films that are nothing but digital noise, which makes Renée Webster’s debut feature How to Please a Woman all the more precious. Webster emerges as a fully formed filmmaker with something to say and intends to do so through pure entertainment and hilarity. How to Please a Woman follows Gina (Sally Phillips), an office worker who finds her life heading towards a rut as she’s swiftly booted out of her job, all while she’s working to reignite a romantic spark in her loveless marriage with Adrian (Cameron Daddo). Noticing an opportunity like no other, Gina swoops in to revive a flailing removal company run by Steve (Erik Thomson) and unexpectedly turns it into a male escort business. Getting to see How to Please a Woman with packed audiences laughing at all the right points is a memory I won’t soon forget, with women of all ages pouring out of the screening saying ‘I wish my husband saw this’ or ‘I need a house cleaner like those guys’. This happened on more than one occasion, showing just how much audiences craved a film that entertained as much as How to Please a Woman did. To quote one audience member I chatted to after a screening as she wiped tears of laughter from her face: ‘I needed that.’

In 2022, Archie Roach was reunited with Ruby Hunter. Prior to his passing, we were gifted with this miracle of a film by Philippa Bateman: Wash My Soul in the River’s Flow. Playing out as a concert film with Uncle Archie and Ruby performing Kura Tungar-Songs from the River, a two-year collaboration with Paul Grabowsky and the Australia Art Orchestra, Wash My Soul in the River’s Flow is as essential as Amazing Grace or Summer of Soul. Footage of interviews from 2004 are intertwined amongst rehearsals and the opening night performance, creating a wholly emotional and soul-enriching experience. As Uncle Archie watches with adoring eyes as Ruby sings in the spotlight, the imagery flows into Bonnie Elliott’s glorious cinematography of Hunter’s Ngarrindjeri country in South Australia. Elliott’s camera embraces the waters of the rivers and the shores that attempt to confine their existence in a breathtaking manner. This is the country that Ruby sings in Ngarrindjeri Woman, this is the home that Uncle Archie sings about in Took the Children Away. Wash My Soul in the River’s Flow changes you, just as Uncle Archie and Ruby Hunter’s music changes you. This film will sweep you up in its wake and carry you along for the ride. It is a miracle.

Set during the 2019 Kalgoorlie-Boulder Mayoral election, General Hercules positions the titular John ‘General Hercules’ Katahanas as the David to the incumbent Mayor John Bowler’s Goliath. Katahanas is a character like no other, a raw bloke born out of the dust with a wild vision for how to better lead Kalgoorlie-Boulder. Director Brodie Poole utilises startling imagery of the growing ‘Super Pit’ that threatens to swallow the town of Kalgoorlie whole as a contrast against the hopes and dreams of the townsfolk. Poole doesn’t lay judgement upon Katahanas or any of the other inhabitants of Kalgoorlie, instead he allows their eccentricities to thrive in the moment, creating one of the most entertaining and engaging political narratives captured on screen in recent Australian history (and given the Federal leaders we’ve had, that’s saying something.) Poole’s fascination with humanity as a whole comes through strong in moments where he lets the camera just roll and capture the absurdity of the voting mind, like when a man walks up to John Bower on the street asking him “Are you the guy in the posters?”, and then demands that he makes the skimpies skimpier. General Hercules is like an opportune find in the wilderness, kicking a dirt covered gold nugget and discovering a wealth of riches. It stands as a triumphant example of what modern documentary filmmaking looks like.

With his second film The Stranger, Thomas M. Wright examines a real-life tragedy through the perspective of the undercover police officer (Joel Edgerton’s Mark) who works to ensnare Sean Harris’ Henry Teague within a manufactured crime syndicate that exists solely to bring him down. The violent act that Henry has been alleged of is rarely mentioned in the film with Wright allowing the echoes of trauma to reflect through the narrative until the soul-crushing conclusion. The Stranger is a meticulous, powerful film. It is also one that plays as another entry in the ever-growing library of Australian films that attempt to reconcile with the violence, trauma and resulting tragedy that has occurred on this broken land. For some viewers, this almost obsessive quality that some Australian filmmakers have with the acts of murderers is too much, creating a pall that hangs over the rest of Australian cinema, but for filmmakers like Wright their films exist to try and make sense of the world that we live in. Best watched when paired with the equally explorative and questioning short film Mud Crab by David Robinson-Smith, a film that also tries to make sense of the violence in this country, ultimately coming to the conclusion that those who inflict brutality on the innocent are crabs in a bucket pulling each other down. In both The Stranger and Mud Crab, hope and optimism are aliens from another universe.

As I write out this list of my favourite Australian films of 2022, a debate rages on social media about the use of AI programs to modify, manipulate, and manufacture ‘artwork’. Each time I see the arguments for and against flit across my screen I’m reminded of the masterpiece of Australian cinema that is Back to Back Theatre and Bruce Gladwin’s Shadow. Lead by a trio of actors (Simon Laherty, Scott Price, and Sarah Mainwaring), Shadow tells the story of a group of intellectually disabled people who commune for a town hall meeting to debate the presence of machines and artificial intelligence in our lives. Shadow confronts its audience with its call to remember exactly what humanity is amidst some seriously wicked moments of comedy (a scene where Scott loses it at the omnipresent three-piece orchestra is one of the funniest scenes in a film this year). There’s a lot to digest here, especially as the gravity of the realisation that we will all be intellectually disabled in the shadow of artificial intelligence sinks in, but Shadow is at its very best with its beautiful and humanistic closing shot. A new benchmark for Australian cinema.

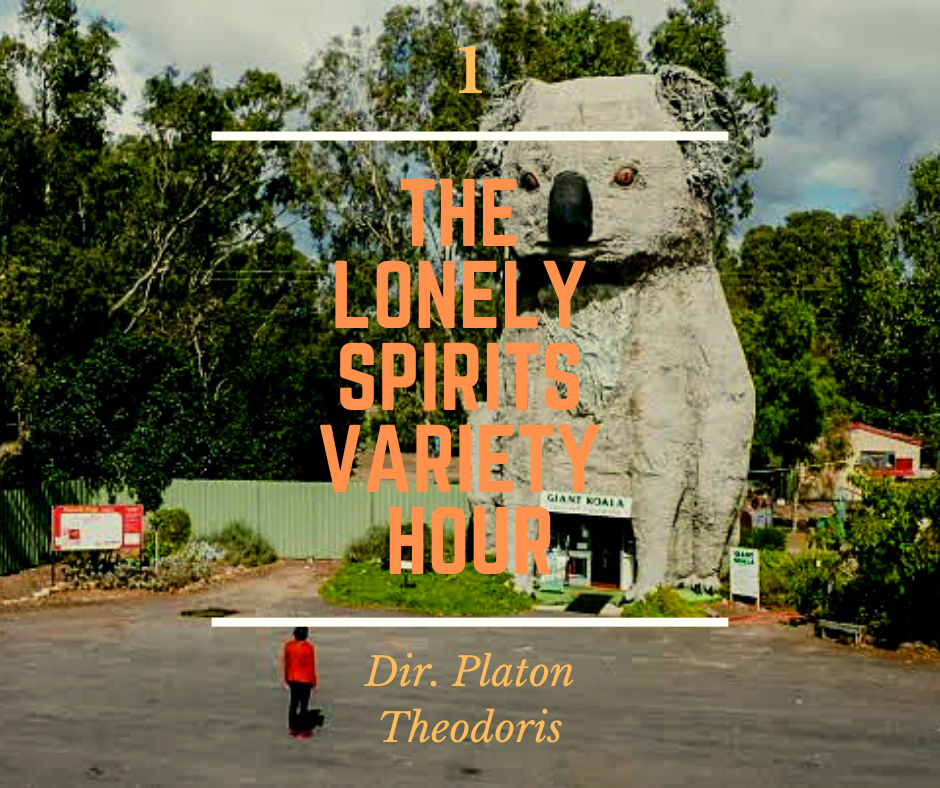

The Lonely Spirits Variety Hour is Platon Theodoris and Nitin Vengurlekar’s wonderfully absurd, hilarious, and moving film about a lone late-night radio host, Neville Umbrellaman (Vengurlekar) beaming his voice into the world from the solitude of his tiny garage studio. It is also the film that I connected with the most in 2022, having left my heart full of both sadness and joy after each viewing. Neville’s radio show is peppered with occasional guests, including visits from Kenneth Wong (Teik-Kim Pok), Yvette (Alison Bennett), and Sabrina (Sabrina Chan D’Angelo). Moments where we see Neville’s family unite around him in a hospital room as he lays dying are interspersed between Neville’s radio ramblings where he ponders about the ethics of household goods as TJ and the Snookergees title song of their 1962 album Purple Carrots plays. Equally absurd are Neville’s encounters with a variety of Australia’s ‘Big Things’; he’s swallowed whole by a big fish, becomes the eye of the Big Merino, and finds love with Sabrina as the red-eyed Big Koala watches on. We carry great films as precious memories of a touchstone moment in our life, allowing them to become part of our souls, and The Lonely Spirits Variety Hour is one such film. In the darkness of a cinema, the blend of absurd ramblings into the void – never truly knowing the audience you’re reaching – with the stark reminder of our own mortality, I felt like I was having my own life presented back at me.

Click over to the next page to follow links to watch some of the films on this list.

Elvis - Baz Luhrmann

Powered byAn Ostrich Told Me the World is Fake and I Think I Believe It - Lachlan Pendragon (Trailer)

TRAILER - An Ostrich Told Me the World is Fake and I Think I Believe It from Lachlan Pendragon on Vimeo.

Jarli - Simon Rippingale

Tangki - Tjunkaya Tapaya & Jonathan Daw (Trailer)

Facing Monsters - Bentley Dean

Powered byWhen the Camera Stopped Rolling - Jane Castle

Powered byThe Dreamlife of Georgie Stone - Maya Newell

Powered byThe Drover's Wife: The Legend of Molly Johnson - Leah Purcell

Powered byAblaze - Alec Morgan & Tiriki Onus

Powered byHere Out West - Leah Purcell, Ana Kokkinos, Fadia Abboud, Julie Kalceff, Lucy Gaffy

Powered byFranklin - Kasimir Burgess

Powered byNot Dark Yet - Bonnie Moir

Not Dark Yet from Bonnie Moir on Vimeo.