Like everyone except the Indigenous people who lived in Naarm, I am an import to Melbourne. I first moved to the city in 1992 and found my spiritual home. There was something so uniquely cosmopolitan about the city that rivalled my experience of other Australian cities. I spent a good deal of time in Sydney (I was born there) but it never captured my imagination the way Melbourne did. In 2010 I moved away for personal reasons and did not return until 2018 – when I did I found the city had changed dramatically over eight years. Cinemas and bookstores I haunted were gone. Carlton, which had been my stomping ground for many years seemed like a ghost of its previous self. I barely recognised the inner city. In eight years my city had undergone huge transformations. Gus Berger’s documentary The Lost City of Melbourne charts Melbourne’s changing faces from the 1870s to the present day with a specific focus on what caused Melbourne to lose some of its most iconic buildings in the 50s and 60s.

Melbourne, as we know it, was founded by two bickering colonialists: John Batman and William Faulkner. One was a newspaper man, the other a publican, and neither can be called a good person. However, it seems fitting that Melbourne was built on the back of journalism and pubs. What really fuelled Melbourne’s development was the post gold rush boom of wealth. By the 1870s Melbourne was the most sophisticated city in Australia. Unlike Sydney which grew organically and haphazardly, Melbourne was a planned city. It boasted some of the most progressive architecture in Australia and had buildings that rivalled cities like Chicago and New York.

The Victorian era magnate E W Cole opened the famous Cole’s Book Arcade which in reality was a multifaceted department store that also provided public entertainment. Melbourne became a city where people paraded (the French would call them flaneurs) to be seen walking the streets for pleasure. It also had a decidedly seedy underbelly, there were no go zones around Lonsdale Street and parts of Bourke Street for fear of criminal attack – however this is no different to any major city.

Melbourne became a hub for theatre and cinema. Not only was Australia the first to produce a full-length feature film The Story of the Kelly Gang in 1906, Melbournians went wild for the Lumiere brothers’ invention and built multitudes of cinemas and theatrical spaces for the exhibition of the new technology. Melbourne’s prosperity and fascination with the arts shaped the city. In almost every suburb there were several cinemas, and only a few survive today – notably The Rivoli, The Classic in Elsternwick, The Astor in St Kilda, and due to Berger’s own work, The Thornbury Picture House.

So what happened to Melbourne to change it from an arts metropolis filled with glorious Victorian era buildings to a city littered with Brutalist office blocks? The answer comes down to a few factors. First of all there was cultural cringe that was brought on by the 1956 Olympics. Melburnians saw their city as outdated and embarrassing to be featured on the world stage. This feeling was not aided by the advent of television around the same time which gave Victorians a look into the wider world, albeit a skewed one. The prevailing sentiment was “modernise” and (un)luckily there was one company more than prepared to take on the task of removing those unfashionable Victorian and Edwardian buildings; Whelan the Wrecker.

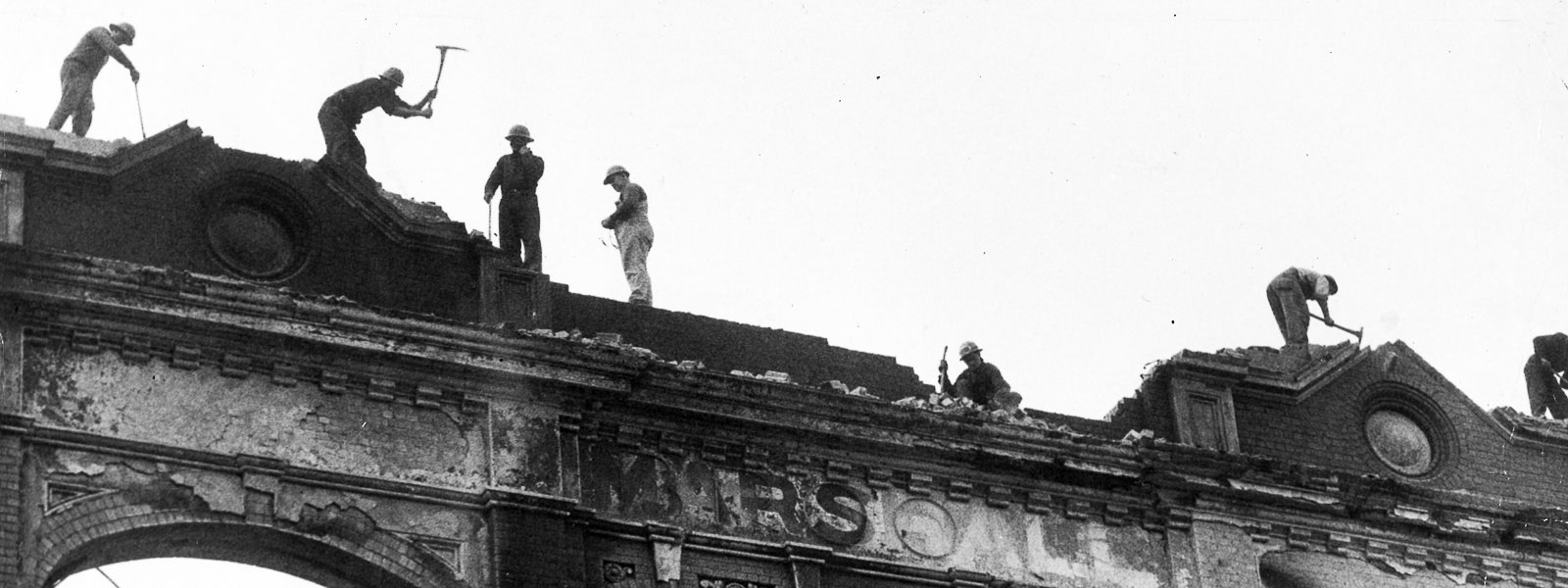

The Whelan the Wrecker company started out relatively nefariously by plundering the sites they wrecked for items they could sell on for a profit. They also recognised that there was spectacle to be shown in the pulling down of buildings and made minor celebrities out of their workers. A Whelan family member is interviewed by a young Barry Humphries in the documentary. Humphries shows incredible restraint as the Whelan son gloats over pulling down the cultural history. As one of the talking heads in the documentary points out, what the Whelan family was doing was “vandalism.” Without any form of National Trust in Australia at the time, the historic buildings of Melbourne were prey to any developer who saw profit in erecting a new office block or shopping centre.

Interweaving historical photographs, archive footage, and interviews from contemporary historians, Berger has made a love-letter to a lost city, yet he isn’t without hope for Melbourne. For all that has been lost he reminds us of what has been saved. The glass is half empty or half full depending on one’s perspective, and it is important to note that cities are changing and evolving all the time. There is a sense of melancholy that Melbourne pulled down its own history not because it needed to be rebuilt after being war-torn, but because profit and cultural cringe pushed the city into destroying some of its most beautiful buildings.

Berger reminds us that the process is still going on. In 2020 developers gutted and destroyed The Palace Hotel on Swanston Street. Melburnians will know it as The Metro. I can’t even count the number of gigs I went to there, it was an essential part of my Melbourne experience, as I’m sure it was to many people. It is now a luxury hotel. I’m hoping that the sweat of hundreds of thousands of young music lovers is soaked into the very foundations of the building.

The Lost City of Melbourne may have problems reaching an audience that isn’t invested in the city, but it does speak to the wider issue of gentrification and capitalist greed and how those factors impact upon the places people live, work, and play. For the people of Melbourne it is a wonderful glimpse of what the city was, and it what it remains. Collins Street still has a “Paris End,” and although we’ve lost a lot, there are many remnants of a golden age, such as The Forum, The Regent, and so many more wondrous places. Melbourne is a city of resilience and a true capital of the Arts, and although the city’s face has changed many times, what is true is that its heart hasn’t.

Director: Gus Berger

Cinematography: Andrew Watson, Radar Kane

Producer: Gus Berger

Composer: Amelia Barden

Editor: Phoenix Anna Cherry

The Lost City of Melbourne: trailer from Gusto Films on Vimeo.