With over 170 Australian features, documentaries, and short films released theatrically, on streaming platforms, and at festivals during 2022, it’s safe to say that the Aussie film industry is shrugging off the post-pandemic blues in a mightily productive manner. The creative results of Hollywood setting up shop down under to escape COVID emerged out of isolation with Baz Luhrmann’s Gold Coast shot Elvis, George Miller’s Sydney-sided Three Thousand Years of Longing, and AACTA-certified trailblazer Chris Hemsworth sticking close to home and family with Joseph Kosinski’s Spiderhead (Queensland) and Taika Waititi’s Thor: Love and Thunder (NSW) all making Australia look as un-Australian as possible.

Out of the shadow of money-rich studios, Aussie indie filmmakers equally thrived with a wealth of creativity and ingenuity that has you wishing that the Federal Government would support the industry more than it already does. Glenn Triggs (mostly) dialogue free Dreams of Paper & Ink told a decade spanning love story with moments of genuine passion, while Sari Braithwaite’s tender Because We Have Each Other brought us into the home of a unique Aussie family, and Catherine Hill presented a day-in-the-life of a homeless woman in the considered Some Happy Day. These are just a handful of independent films that worked hard to tell Australian stories and keep Aussie voices on screen.

Before I jump in with my favourite Australian films of 2022, a few notes about the list itself. Out of the films released, I watched 101 Australian features, documentaries, and short films. The below list is the result of a wealth of difficult decisions of which films to include and which films I had to leave off, all of which shows that 2022 was a great year for Australian cinema.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers readers are advised that the following article contains images and names of people who have died.

Once you’ve gone through the 2022 list, check out the 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, and 2016 lists.

Mob stories are a dime a dozen, so when something neat and entertaining plays around with the format, it’s worthwhile taking notice. Such is the case for co-writers Riley Sugars and Chloe Graham’s darkly comedic Hatchback. Sugars takes directing duties, immediately situating himself as a filmmaker on the rise to keep an eye on, harnessing the acting brilliance of Stephen Curry and Jackson Tozer to tell an affable tale of a mob cleaner Vince (Curry) who enlists his less-than-bright brother-in-law Ted (Tozer) to help dispose of a body. Things immediately go awry when instead of nicking a van, Ted steals a hatchback, causing an escalating series of comedic exploits from trying to fit the rapidly stiffening corpse into the boot of the car, to one of the best tomato sauce gags in a long while. Hatchback delights with the push-pull relationship between Vince and Ted, two mismatched fools in a situation that simply cannot end well. I cannot wait to see where Sugars, Graham, and Tozer go from here.

There were two outrageously expressive music-focused films that struck a chord with me in 2022: Baz Luhrmann’s epic Elvis overwhelms the senses as Austin Butler gives a transformative turn as Elvis that shoots shivers down your spine with the way he becomes possessed by the spirit of the King, and Seriously Red, Gracie Otto and Krew Boylan’s ode to Dolly Parton, believing in your true identity, and even the King himself (at least Rose Byrne’s version of Elvis that is). Luhrmann’s Elvis is as Baz Luhrmann as a Baz Luhrmann film can get, with frenetic editing, electric shots, and dizzying sound design that leaves you feeling like you’ve just eaten all of the fairy floss at the Royal Show. Naturally, with Hollywood funding behind it, Elvis has the edge on Seriously Red, but both carry a level of affection and adoration for their chosen music icons that is undeniable. Equally so, Elvis is an immediate classic, securing a swag of AACTA awards that remind just how Australian this deeply American story is, and while Seriously Red was not exactly critically embraced, it carried an emotional authenticity that resonated powerfully with me, and really, isn’t that all that we want from the films that we dedicate our lives to watching?

Read Andrew’s interview with Lachlan Pendragon here

The creativity that exists within these three stellar short films highlights a new wave of Australian animators on the rise. Lachlan Pendragon crafted the existential stop-motion animated comedy An Ostrich Told Me the World is Fake and I Think I Believe It by himself during COVID lockdown, harnessing a delightfully meta narrative about an office worker realising he’s being manipulated by a greater figure and turning it into an award winning success (Lachlan won the Gold medal at the Student Academy Awards). Chantelle Murray and Simon Rippingale’s aspirational and joyous short Jarli showcased the story an Aboriginal girl (vibrantly voiced by Madeleine Madden) who dreams of flying into space (a journey which the film was able to achieve in 2022) with a delightfully Australian visual style that left me yearning for a feature length film with this look. And then there’s Tjunkaya Tapaya and Jonathan Daw’s heart-warming animated short Tangki (Donkey) that utilises the work of the Tjanpi Desert Weavers to retell the story of how donkeys were introduced to the desert community of Pukatja (Ernabella), and the relationship that the Anangu people have with the tangkis, leading to a visually unique and expressive style of animation that leaves you feeling like you’re sitting in the desert with the community and seeing the story being retold in front of you. Each of these shorts challenged the notions of what traditional animation could be, and in doing so showcased the possibility of creativity and imagination going forward.

Across his career, legendary cinematographer Rick Rifici has helped define our relationship with the water through his ability to immerse audiences in environmental situations that seem almost impossible to capture. With Facing Monsters, alongside director Bentley Dean, Rifici pushes the realm of surfing cinematography to the next level as they detail big wave surfer Kerby Brown’s exploits in the ocean, throwing his body (and life) on the line as he tackles some of Western Australia’s most overwhelming and dangerous slab waves – a thick wave that moves quickly at a low height, breaking on reefs from deep water. Paired with Brown’s personal journey with mental health, Rifici’s cinematography stuns the senses, amplifying Facing Monsters into a truly powerful experience that has had Western Australian cinema-going audiences turn out in droves throughout the year to witness the doco on the big screen at Luna Leederville.

Read Nadine’s review of The Lost City of Melbourne here

It takes a considerate eye to look at the destruction of a city over the decades and craft a film that carries a level of awe and wonder for the culture that lingers in the rubble of gentrification and modernity. This is what director Gus Berger has managed to do with his expansive historical documentary The Lost City of Melbourne. Utilising the Melbourne lockdowns to take a journey through the Victorian history books, Berger witnessed a city that is at threat of losing its cultural identity and crafted a film that calls for an end to the gaping maw of the kind of homogenised destruction that has swept through cities around the globe. Berger reflects on what makes Melbourne unique, and in doing so shines a light on the structural ghosts that once dominated the cities skyline, highlighting the importance of communal venues like cinemas and theatres. When paired with the equally important Splice Here: A Projected Odyssey from fellow Melbournian Rob Murphy, The Lost City of Melbourne helps remind audiences what we stand to lose as we race into a future that prioritises rapid infrastructure progression over fortifying cultural identities and institutions.

Read Andrew’s interview with Tim Baretto here

Within Tim Baretto’s sun-kissed summer tale Bassendream there is a wonderful feeling of reclaiming the positivity of nostalgia from the manner that it has been weaponised by certain fan groups around the world. Now, that’s not to suggest that Bassendream is a pop culture focused affair, in fact it’s quite the opposite of that. Instead, this is a grand ode to Australian suburbia, to the ‘dry heat’ of West Aussie summers, to the winding down of the school year and the possibility of adventures over the holiday break. It’s a film about the cusp of new friendships and the unexpected dissolution of hard-earned bonds, to mucking around with mates and pissing off old folks with shenanigans. It’s the sound of hearing Paul Kelly’s Dumb Things for the first time and thinking ‘fuck, this song gets me’. It’s the anger at a sibling for tearing apart your prized basketball collectors’ card. Baretto’s film is an experiential one, gleaned from his mind like something that only the outer-suburbs kids can do. Bassendream was shot on film, evoking both the pastels of nineties attire, almost appearing at times like the faded curtains that daylight savings alarmists ranted and raved about in the letter’s column of The West Australian newspaper. There’s a reason why there was a tangible electricity in the air after the sell-out screenings at Perth’s Revelation Film Festival and it’s because a unique slice of Australiana was captured on screen with love, dedication, and authenticity in a manner that has never been captured before.

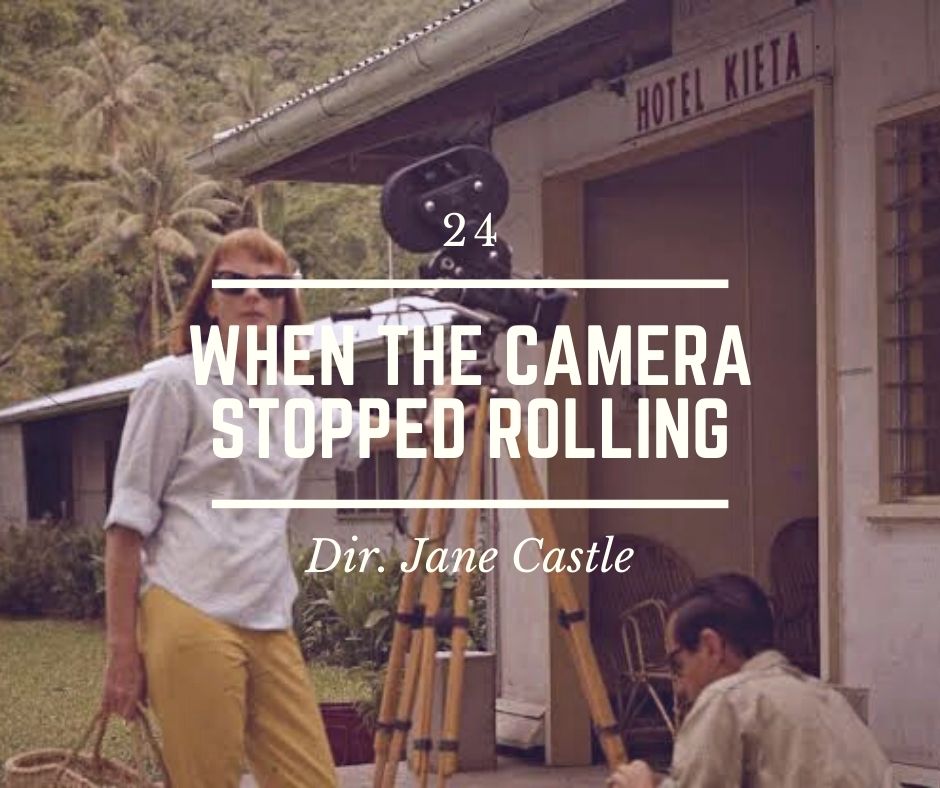

Read Andrew’s interview with Jane Castle here

The art of reflecting on the past with awareness of its impact on the present is a difficult thing to master, but filmmaker Jane Castle managed to do exactly that with her familial documentary When the Camera Stopped Rolling. Initially conceived as an intellectual film about death, When the Camera Stopped Rolling evolved over almost ten years of production into being a reassertion of Jane’s mother, Lilias Fraser, into the history books of Australian cinema. Brilliantly autobiographical and revealing, When the Camera Stopped Rolling is at times a difficult watch as Jane works through her relationship with her mother through pristinely presented archival footage (which occasionally plays like a silent film) with a level of vulnerability that gives way to an emotionally enriching experience come its close. Ultimately, When the Camera Stopped Rolling showcases a labour of love for parents and the culture that they introduce their children to, while also recognising the struggles that emerge from a crumbling mind.

There’s a deliberately ethereal quality to Maya Newell’s latest documentary The Dreamlife of Georgie Stone that elevates the story of transgender rights activist Georgie Stone. The Dreamlife of Georgie Stone is framed around Georgie’s fight against the Family Court to allow transgender kids to begin hormone therapy, alongside the support Georgie’s family gives her during her own transition journey. It’s in the telling of these two stories we see the emergence of an activist, an icon, an emerging leader, and an actress. Maya Newell’s films celebrate the importance of identity and reinforce the need for community and familial support to allow those identities to flourish. Her work is always collaborative, acting as a facilitator to help share her subject’s stories with the world, a point which is amplified by the abundance of home video footage of Georgie growing up with the support of her father. This is an all-embracing documentary, one that makes you grateful that there are selfless people like Georgie Stone in the world fighting for those who may not be able to fight for themselves.

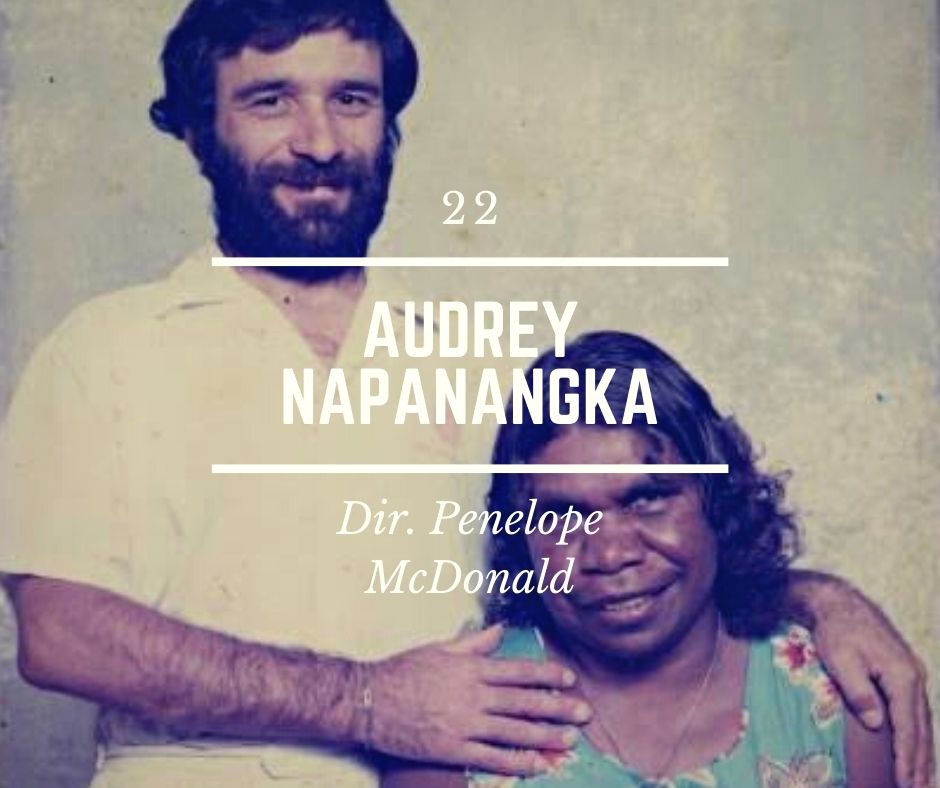

Penelope McDonald’s delightful and devastating documentary Audrey Napanangka was filmed over ten years, telling the heart-warming story of Warlpiri woman, Audrey, her Sicilian partner Santo, and her foster family as they live life in Mparntwe (Alice Springs). The family aspect continues off screen, with Penelope’s son Dylan River assisting with lensing duties, giving the documentary a communal, all-embracing feeling that leaves you grateful for the experience of spending a decade with Audrey’s family. While there are moments of tragedy, Audrey Napanangka shows that time spent with Audrey’s generosity is a great privilege, ultimately reminding that the complexity of life is what makes it worth living, especially when surrounded by people you love.

William Duan’s precise and precious short Tuī Ná tells the story of David (Yipeng Xu), a 17-year-old Chinese boy discovering his queer identity amidst his dedication to his mother and work. Immaculately shot and framed, Tuī Ná aches with yearning for a sense of place in the world. This feeling is paired with David’s burning desire to embrace the body of another man who also craves his body. Christine Cheung edits each motif together in a delicate and tender manner that shows ultimate compassion and consideration for the complexity of the story that Duan is showing here. Intertwined with shots of flowers and David look straight into the camera are moments of David and his mother leaving offerings and prayers for David’s grandmother who has recently passed. At the close of Tuī Ná, I just wanted to give David (and by extension, William) a hug.