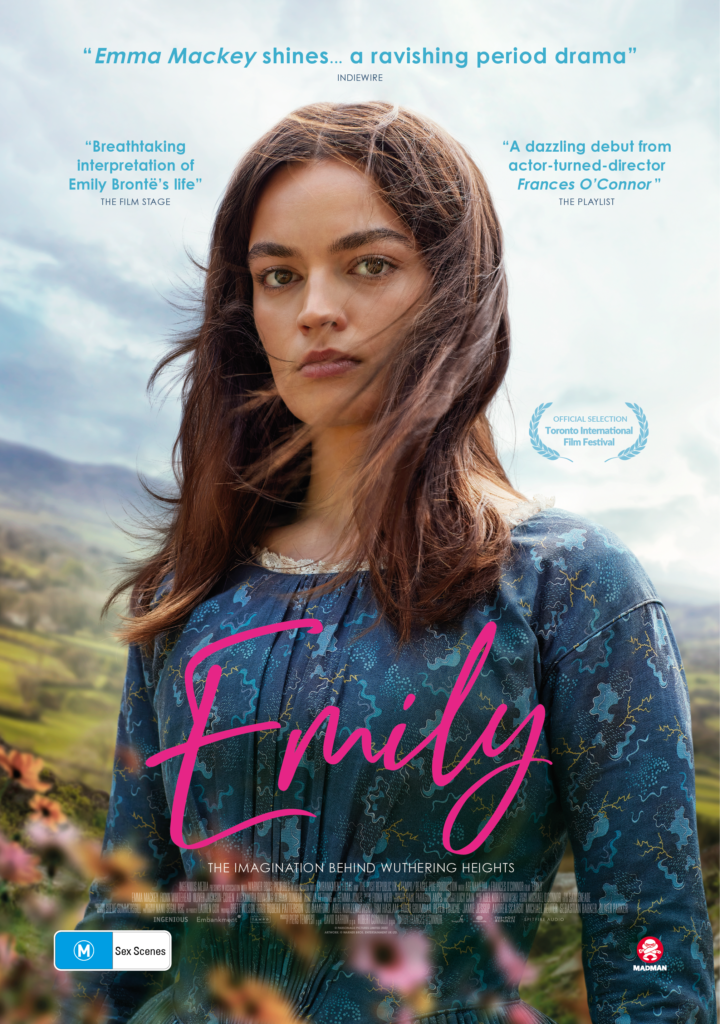

Frances O’Connor is no stranger to costume dramas and period films, having featured in an impressive array of notable films such as Patricia Rozema’s Mansfield Park (1999), Oliver Parker’s The Importance of Being Earnest (2002), and even James Wan’s The Conjuring 2 (2016). Now, O’Connor has taken the move into writing and directing with her first feature film Emily, telling a fictionalised version of the life of Emily Brontë (played with an astonishing turn from Emma Mackey), exploring the relationships of her life, including a painful and powerful bond she has with William Weightman (Oliver Jackson-Cohen).

Emily left me stunned and moved like precious few films have done recently. Precisely made with O’Connor’s keen vision for how she wanted to tell this story being immaculately and tenderly presented on screen. Mackey’s performance sweeps you up in her wake, just as Nanu Segal’s cinematography embraces her presence and the world around her. Equally so, the era is presented in a manner that feels appropriate, with shots of dust hanging in the harsh cold of the English winter air accentuating the stillness of life, all the while it’s contrasted by the openness of the fields near the Brontë’s homestead. Emily sways between genres effortlessly, shifting from drama, to romance, with an element of horror added to amplify the ‘weirdness’ of Emily by way of an instantly iconic scene featuring a mask.

Frances O’Connor’s writing and direction carries an energy to it that feels fresh and vital, like this is a story that has been blooming within her mind for years, itching to escape and be told on screen. In this interview, Frances talks about what it feels like to get that story on screen, her collaborative creative process, and more.

Emily arrives in Australian cinemas on January 12th and is a film you simply cannot miss on the big screen. I know I’ll be rushing back to be embraced by this film once again.

How does it feel to get Emily’s story on screen after having it in your mind for so long?

Frances O’Connor: It feels magical. It feels like this miracle where what you saw in your imagination, everybody went “yeah, we like that same idea.” And then it gets kind of conjured, so it does feel quite magical. I’ve really loved Emily Brontë for a long time. I really like what she represents. I think she’s been forgotten a little bit, and has always been in the shadow of her sister, Charlotte, so I wanted to bring her into the centre of her own story as rebellious act, in a way.

This is a very precise film. I’m in awe of the shots, the score, the editing, and the performances. Can you talk about the collaborative approach to create a cohesive work here?

FO’C: I started with a director statement that I gave to everybody coming on the project, and then I did a big look book. It had images, and really helped people see, as an opening offer, how I saw the film. I think a lot of people found that helpful. What was great is that was a jumping off point for everybody to offer up what they felt they wanted the film to be through their particular area.

With Nanu [Segal – cinematographer] and I, she also did look book as a guide for her vision. It was quite a tight shoot of about six weeks, it was very quick; we planned for about four months before, so I had a clear idea of how I wanted to shoot it. I wanted to shoot it in a very gentle handheld way. My touchstones for the film was Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Biutiful (2010) and Jacques Audiard’s Un Prophète (2009). I love those films because they’re kind of gritty, but at the same time, they’re beautiful and poetic. I love that style of storytelling.

With Abel Korzeniowski [composer], I sent him a cut late in the day when I thought it was at its strongest to just see whether he would be interested in doing the score, and he just loved the film and came on board, which is a very lucky with his availability. We talked about the music being experiential, that it emulated what she was in the middle of feeling or experiencing. It was always about what she was feeling and what she was thinking. Apart from a little bit where we slip into William Weightman’s (Oliver Jackson-Cohen) perspective towards the end of the film.

It’s interesting with Sam Sneade [editor], it took a while to find an editor and I kind of took a risk on Sam in that he hasn’t worked in long form narrative in a long time, but his cutting style is really beautiful. He did Sexy Beast (2000) back in the day and Birth (2004). The way he cuts, there’s something very interesting about it. And he’s very, very collaborative so I really felt like I got to make the film I wanted to make in the edit. And he’s really fun too.

What I was in awe of is the way you show the internal monologue of somebody as they’re living their life, which is very hard to do on screen. It’s additionally very hard to present what being an introvert is like as well. And yet, I saw a lot of myself in in Emily. I’m curious for you, how you went about creating and crafting that sense of introversion, that feeling of being an introvert?

FO’C: Oh, I’m so glad you said that. I’m an introvert too, so I see a lot of myself in Emily. I think it’s an interesting dilemma, how do you help the audience connect to Emily and understand what she’s thinking and feeling? We’re also really aided by Emma Mackey, who is just really very good at communicating things organically through her face. You read her face and her thoughts are very interesting. We decided one of the things we were going to do is to keep coming back to the centralised shot of her in the middle of the frame, really close looking out, so it helps the audience connect to her and have a private moment with her where the only person she’s really looking at is us.

We did have coverage of other people, but we did this thing where we cut the scene so you’re listening to other people, but you’re with her listening to people. She spends a lot of the time of the film either looking or listening to other people that were looking at her. I think that helps as well. It was a really interesting dilemma. Of course, the music and the sound help, and pushing her breath above other people’s breath unconsciously helps you connect, I think.

You’re working with a wide array of producers here but one of the key people is Robert Connelly, who you’ve worked with before [Three Dollars, 2005] and you’ve got a great relationship with. Can you talk about that creative relationship?

FO’C: I was shooting The End (2020) in Queensland and was working on Emily and I said, “Rob, could you read my latest draft and see what you think? I feel like it’s pretty close to being ready.” He’s got two teenage daughters and he said, “I think there’s something here. I think you’ve really got something.” Then he connected me with his script editor Louise Gough as part of his company, and Louise helped me polish the script. Then he helped me connect to Embankment Films who connected us to the main producer Piers Tempest, so the film kind of got up that way. That was how he helped, in a practical way, get the film up.

He helped me so much through the shoot and through prep. I could always call him. It was in the middle of a pandemic, so he couldn’t even come over, which he was planning to do originally, but he was always there at the end of the phone to talk me through things if I felt like I was feeling unsure of something. He’s been all the way with me on the journey, so it’s been it’s been really special to share it with them.

One of the key threads throughout Emily is the line “freedom in thought” and I’m curious what that means for you as a creative person?

FO’C: To be honest, I’m not sure where it came from, it’s not in Wuthering Heights. In a sense, those characters do have a lot of freedom in their thoughts in terms of half the time we trap ourselves with our own thoughts, and the only thing getting in the way of ourselves, in terms of becoming a creative person, is not believing in yourself really. I think that’s half the struggle. Ironically, Branwell (Fionn Whitehead) writes on his arm ‘freedom in thought,’ but really, it’s his own thoughts that trap him. The irony is it’s that kind of youthful hope of freedom in thought. To these characters, it’s thoughts that ultimately almost destroy Emily, it destroys Branwell, and it destroys Weightman; his thought is “there something wrong with you, there’s something ungodly about you.” It’s an interesting paradox.

You’ve got an interesting career where you’ve both worked at home and afar and I’m curious how the Australian identity plays into your work. Do you think about it much when you’re working overseas?

FO’C: I tell you what, when I was shooting this film, whenever things were not looking good, and I wasn’t getting what I needed, my Aussie accent got so strong. Like “sorry, I don’t think we should give you that,” and I’d be like, “nah, I want it,” and my Aussie accent just came thick and fast. Since I’ve been away for the pandemic, I feel like I’m sounding more English but who I really am is an Australian. And part of being Australian is that rebellious spirit, which is also in Wuthering Heights and in my film, so I feel like I’m very much an Australian and an Australian creative. I think that’s really served me well working internationally. Aussies have that great sense of spirit about them, and that sustains you when you’re working away.