Note that this interview contains mentions of extreme violence and trauma.

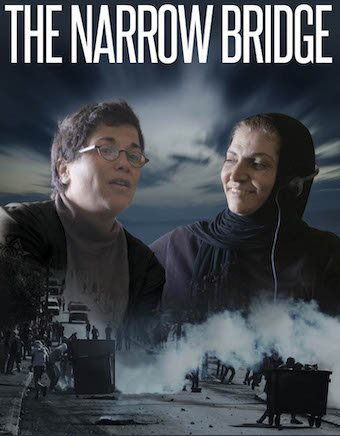

Australian director Esther Takac’s profoundly humanist documentary The Narrow Bridge brings together people who have lost loved ones in the decades long war between Israel and Palestine. Her main subjects Meytal, Bassam, Rami, and Bushra each lost a family member during the conflict. Meytal’s father was hacked to death by Palestinian youths. Bushra’s son was murdered by Israeli fighters. Rami’s daughter was killed in a suicide bombing while getting schoolbooks. Bassam’s daughter was shot outside her school. Coping with enormous trauma and pain, these survivors of unthinkable tragedy decided to reach across the Israeli/Palestinian divide to help create a grass roots peace movement based within the Israeli-Palestinian Bereaved Families organisation.

Esther Takac’s documentary filmed over a number of years (beginning in 2017) charts the immense bravery of her subjects and what they are willing to risk for change. With an ultra-right-wing government in Israel tensions are burning. For some of the participants even being in certain areas is illegal. Esther Takac, a trauma psychologist, earned the trust of the participants and lets them tell their stories. Facing opposition not only from each of their cultures but sometimes from friends and family, the participants’ commitment to reconciliation and peace is inspiring and honours those they have lost in a beautifully hopeful way. Grief can galvanise people further into hate, but for Meytal, Bassam, Rami, and Bushra the process has meant coming to terms with devastating loss and working to achieve a peace that means no further families will suffer like they have. A crack of light has opened for them and letting the light shine in means that perhaps one day an enlightened society can emerge where people see each other as human beings, not enemies.

Nadine Whitney spoke to Esther ahead of special screenings of The Narrow Bridge in Sydney and Melbourne.

Join the subjects of the documentary, best friends and peace activists Bassam Aramin and Rami Elhanan, for these two very special Q&A screenings.

Thursday 18 May @ 7.30pm

45 St Paul’s Street, Randwick, NSW

Sunday 28 May @ 4.00pm at

Classic Cinemas, 9 Gordon Street, Elsternwick, Vic.

Nadine Whitney: I watched The Narrow Bridge and I cried, I felt despair, and then hope. The documentary is getting screenings during an intense time in Gaza. We are also seeing a rise of neo-fascism even in places like Australia.

Esther Takac: I was at a pro-democracy Israel rally this morning supporting the grass roots protests in Israel protesting against the judicial overhaul slash coup that the current right-wing government is going to try to push through.

NW: I have been watching the conflict for years and as an outsider I’ve never properly been able to comprehend it. But, you were there, on the ground and you were talking to people who have suffered immense trauma through the never-ending war.

ET: To give a bit of context, I’m a child and adult psychologist in my day job. I worked in the public sector for a long time, I was also involved in the investigation into child sexual abuse. I now have a private practice. I wanted to do some kind of giving back and so I have been going and working a month a year as a voluntary psychologist in the paediatric wing on the Hadassa hospital in Jerusalem where the patient body is split about fifty-fifty between Israeli and Palestinian children and their families.

That’s how I got involved in this world. I met people through that work at the hospital who had lost family members and through that I went to the joint Israeli Palestinian Memorial Ceremony (2017). I was completely blown away by the power of it and I thought people outside Israel and Palestine need to know more – people inside need to know more – but the world community needs to be aware of how these people are role models for being able to manage trauma and being able to alchemise it into something positive and also as a model for conflict resolution.

NW: It is such a powerful documentary hearing first-hand accounts from people who lost their loved ones and how they lost them, and how none of it makes any sense. They had so much anger, but they turned it into compassion for each other and “the other.”

ET: Israeli-Palestinian Bereaved Families organisation did an amazing campaign where they did a blood drive where Israelis donated blood to Palestinians and vice versa and the byline of that campaign is “Would you hurt someone who has your own blood running through their veins?” Which speaks to the idea of can you hurt someone if you really understand their story. It is Meytal who says, “The chance of hurting someone when you really know who they are lessens dramatically.”

NW: That is such a resonating and important line and critical to the documentary’s thesis. There were certain aspects I was blown away by, such as the idea that so many Palestinians either are ignorant of or deny the existence of the Holocaust.

ET: Bassam says he grew up thinking the Holocaust was a big lie. That’s not uncommon. That was part of the false education given to people. Palestinian people felt that Jewish people were given the opportunity of developing a state in Israel after the Holocaust partly because of the Holocaust. They were resentful of it and asked, “Why are we paying the price for the Holocaust?” I think that’s part of the background of trying to delegitimise the Holocaust.

It was only when Bassam, a once radicalised Palestinian youth who spent seven years in prison watched a very well-known film about the Holocaust he changed. What’s amazing is that Rami’s own father is a Holocaust survivor. In Israel on Holocaust Memorial Day there is a one-minute siren that goes through the whole country and everybody stands still. Now Bassam stands still at that time.

NW: The relationship between Rami and Bassam is inspiring. They are like brothers.

ET: They really are. Rami and Bassam will be at the screening in Melbourne on Sunday 28th May. They have been touring with the documentary all over the world.

NW: The Leonard Cohen song Anthem (performed at a concert in Tel Aviv) comes through the film in the idea of a crack of light so often – the crack of light that shines on the idea of peace and but also the notion that a crack of light is a way to start shining on learning about your prejudices and opening up to other people. I think Cohen would be so pleased to see the documentary.

ET: It’s so amazing I got that. Leonard Cohen dedicated that song to the Israeli-Palestinian Bereaved Families Organisation and gave fifty percent of the profits from the concert to the organisation. I saw a clip of the concert and I reached out to Leonard Cohen’s manager and he was supportive. I really feel that Leonard’s statement about the song is powerful. “This is a response to human grief, a radical, unique and a holy, holy, holy, response to human suffering,” is the heart message of the film.

NW: Documentary filmmaking is obviously very different to your day-to-day career. What did you have to learn to get behind the camera?

ET: I had to learn a lot. This is my first film. I’ve got a feature film script sitting in a drawer. I wrote that years ago. I’ve always had a creative side. Sometimes it feels like a curse, but truthfully I love it. It means I have to do all these projects I never get any money from. I’ve published three books also. The next thing that came to me was something visual, so I went and studied scriptwriting and I was on the road with this feature film script but when I went to the 2017 ceremony I felt that there was a story that had to be told so I studied documentary filmmaking.

I was very lucky to find great Israeli and Palestinian cinematographers and even luckier to find two incredible editors who I worked very closely with. I know there are some directors that hand a film over to the editors, but I sat with my editors and became very good friends with them. I thank them for making the film look so beautiful.

NW: It does look beautiful. There are so many wonderful shots of the area where you are concentrating on trees growing in impossible places, for example. The idea that life can thrive in difficult spaces.

ET: I know which tree you’re referring to. A tree that is growing on its side in the desert. I put that one in there as a distortion. Things seem so out of kilter. I was conscious of the theme of olive trees throughout the film. The olive tree is such a powerful symbol to both peoples. And the fact that the olive tree is an international symbol of peace is so ironic in an area where there is anything but peace. The Palestinian national poet writes a lot about the olive tree and the olive tree is important in Jewish tradition way back to the olive branch that the dove brings to Noah. The Jewish people see themselves as an olive tree that was uprooted from the land of Israel and has now found its place back there.

NW: The Narrow Bridge is an impact film. Can you tell me a little about how the impact campaign has been going?

ET: When you asked about my experience of making the film it has been really hard work. I am the ‘everything’ writer, director, producer. I did a crowd funding to raise funds. Film Victoria gave a small amount of money because they believed in the film. On the website there is some information about the goals of the impact campaign.

There are lots of things that can be done with this film both within Israel and Palestine and across the world. Essentially I’m looking at doing a TV version of the film around 55 minutes with Hebrew and Arabic subtitles that can be supplemented with a study guide that can be used as a basis of workshops in Israel and Palestine.

There’s this whole concept of transitional justice which was used in Northern Ireland and South Africa and it’s about that bottom-up grass roots peace building. $54 per person was spent in Northern Ireland and $1.50 was spent in Israel and Palestine. I’m trying to get it on an Israeli broadcaster. I want to use it to break down stereotypes about Muslim and Jewish people, break down people’s preconceived ideas about the conflict and give some hope for resolution. So the documentary is a tool for organisations working with conflict resolution, but it is also a tool for organisations working with trauma because I think it’s really useful to show the stages that can happen after trauma. How it impacts upon your body, your mind, your spirit – the depression, the anger, the isolation, but also how things can change. It shows a pathway to post-traumatic growth which we need to know more about.

It screened at the Jewish International Film Festival. We are hoping that we can have some more screenings at this stage, but they aren’t locked in yet. It has had festival screenings across the world.

NW: I can’t wait to recommend the film to a wider audience. It is an absolutely essential piece of filmmaking. My heart broke a thousand times and then it was healed and broken again.

ET: I think that the Israelis and Palestinians are two traumatised people clinging to this tiny sliver of land. I know that there is a lot of trauma in both in both populations. I know that conflict increases trauma, that’s obvious, but trauma also increase conflict because people who are traumatised are often hypervigilant and over-reactive. There’s all that side of trauma that can cause people to lash out.

NW: For some of your participants that was their immediate reaction, to lash out. But the question that was raised was what good would that do? It wouldn’t bring back the dead.ET: When I went to that first concert in 2017 it wasn’t that organised, and we had to walk through the right-wing Israeli protestors who were cursing and spitting at the people. I was thinking to myself what would make people so vehemently angry and bring them out on Memorial eve to do protest this instead of doing their own thing, and my guess was some of those people would have lost people in the conflict as well, but their pain has taken them in a direction of revenge, ultra-Nationalism and patriotism.