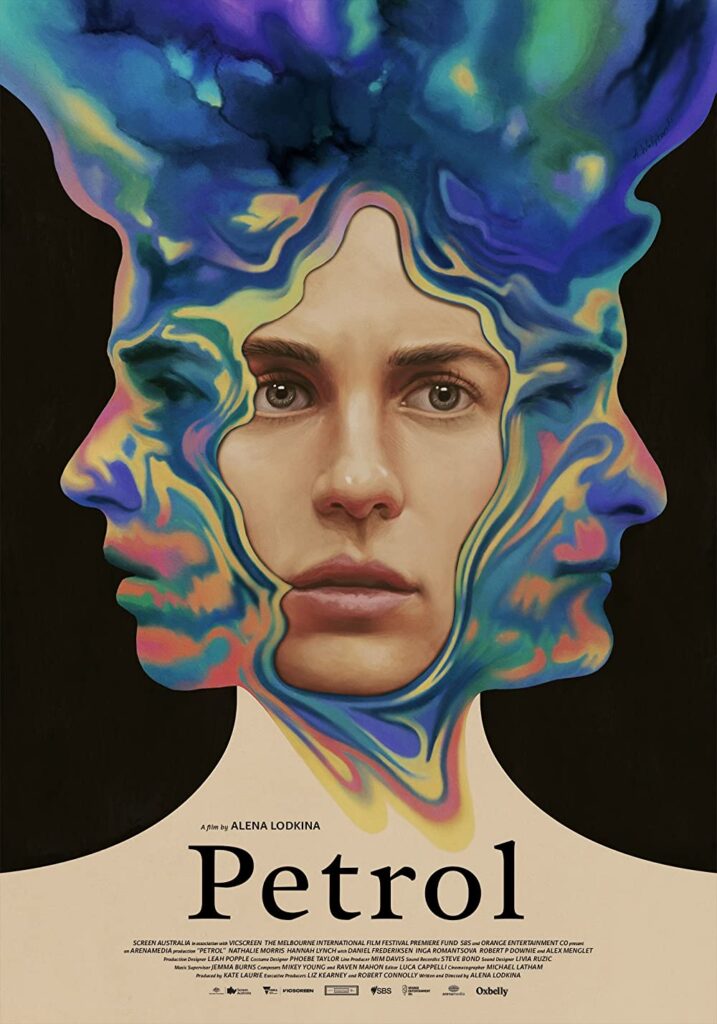

Alena Lodkina’s second feature film Petrol had its domestic launch at the Melbourne International Film Festival alongside a wealth of other Australian films that presented the Melbournian landscape on film. It tells the story of Eva (Nathalie Morris), an emerging filmmaker who encounters the enigmatic Mia (Hannah Lynch) while she is scouting for locations. Over the course of the film, the two flow in and out of each other’s lives, influencing, shaping, and changing each other in tense, curious, and playful ways, collectively orbiting the world of Melbourne art, ultimately questioning relationships with reality and fiction. At times, Petrol is charming and sweet, leaning into a whimsical view of the world, only to have characters pulled out of that mood and into the reality of the world around them.

In this interview taken ahead of the films release, Alena talks about her vision for the film, working with cinematographer Michael Bentham, and the impressive sound recording, design, and mixing from Steven Bond, Livia Ruzic, and Keith Thomas.

Petrol will screen throughout the Melbourne International Film Festival with Q&A sessions across the festival, and will have screenings at Cinefest Oz later in August.

I interviewed you [for] Strange Colours, and I remember you mentioning you were about to go into production on Petrol. It’s different, but it’s quite beautiful. It’s really fascinating. Congratulations.

Alena Lodkina: Thank you. I’m curious for those who have seen Strange Colours how Petrol will come across? Because I think they are really different, but they’re also a little bit similar in some ways. Some people have told me they see so much similarities between the two.

I see similarities. These two characters are effectively looking for their place in the world, some kind of purpose or connection or realisation of who they are. In Strange Colours that’s with her dad and trying to discover [herself in] that, and then [in Petrol] it’s with a stranger who she gets to know, and [builds a] relationship and friendship with. It’s this balance of darkness and then lightness and playfulness. How long did you have this idea rolling around in your mind?

AL: It’s been so long actually. Probably some seeds of the story, the kind of world and the characters were in my mind even before Strange Colours or around that time. Whatever random notes [I wrote] was probably before I even wrote the script for Strange Colours. So it’s been a really long, long kind of stewing process for Petrol. The original documents with the notes that I started on my computer was called Petrol, so I just kind of stuck with that name, because I’ve always liked it. And it had this kind of sentimental value for me as well.

After Strange Colours I almost immediately started working on the script, but it took ages and went through different iterations. And when I started writing, I didn’t know what kind of shape the story would take. I just knew how it would start and who the characters were and the feeling of – it’s always kind of similar for me starting on a project, I have to have a feeling that I have to hold on to. Then the story kind of shapes itself. I was writing the script for at least three years. We finally we got the film funded, amazingly, early last year, and we were in production mid last year.

It’s crazy, I can’t believe I made a second film. It’s such a huge challenge in Australia to get your second film funded.

You’re part of a group of people [alongside James Vaughan] who work together and in the orbit of one another alongside Amiel Courtin-Wilson. Is he a bit of a mentor for you?

AL: Yes. I guess it’s relevant to say because this film is set in Melbourne, and it’s like a real Melbourne film. I’ve been living there for ten years, if not more. I moved to Melbourne originally, because I had met Amiel, and I just graduated from uni. I came across his film Hail, and I thought that looked amazing. He was working in this kind of space that was exactly what I was interested in, which was working with non-professional actors and blending different stylistic documentary, non-documentary. I don’t know what you would describe that as, I guess people used to use the word hybrid a lot, which I think is not used as much anymore. But this new realist kind of space.

And I was like, “I need to meet this guy.” And then I just reached out to him, and he said, “Oh, we have this big warehouse in Melbourne. And you can intern. Is always need collaborators [and] people to do stuff.” And that just sounded great. And I moved to Melbourne and ended up meeting all these people who were working with him, there was this kind of orbit around him.

I also worked on his film The Silent Eye. I edited that actually, which was a really cool experience going to New York and working on the edit of that and meeting Cecil Taylor and getting to know a little bit more about how Amiel works. He’s been a friend, and an important figure for me.

Let’s swing back to Petrol. Is there an autobiographical tone, or form to this particular story? It feels like you’re pulling from a bit of yourself here.

AL: It’s a really obvious question, in a good way. And in a way, it’s obviously autobiographical, the similarities between the character and me are really clearly there. But in reality, it’s more of a personal film, rather than autobiographical. The whole story is completely fictional, but it comes from really personal observations and experiences. My model for that, working with a character who’s similar to you was [that] when I was writing the script, I was reading Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, and I really love the way that that work is so obviously his wife and his world, but it’s not. And the characters are actually, in fact, completely different to him. And, it is almost like an autobiography, but it’s not.

I’m interested in how you can take from your experience of life, and yet create a work of fiction. I was never interested in telling my story, the migrant story or even the filmmakers’ story. It’s not even that. It’s just the film happens to be fed by intimate and kind of personal observations of life. And the more intimate and personal aspects of the film are actually really tiny things like objects, or some insignificant phrase that was borrowed from an overheard conversation.

Also, the way that I was writing the film was not so much pulled from diaries, but more a diaristic process, in that I would take notes of things I’ve seen. I guess, [that’s] the way that many writers work, probably without us knowing, that you’re just kind of constantly taking notes about things you observe. And then somehow they enter the story, but not necessarily in the way that you think they would.

That leads into something which I found really fascinating, was [how] it plays with the notion of what film can be. Our first introduction to [the personality of the film] is the font. I love the font choice.

AL: It’s so funny because I just did an interview before this other person said exactly that, “The font! Yes!”

Can you talk about the choice of that font?

AL: We did work with a designer [and] I had a very clear [idea of] the colour, I really knew what I wanted. I guess I just love those kinds of simple big fonts in films that are classic in some way, but then also has like a bit of an 80s vibe. Maybe I was watching some late 70s Brian DePalma and 80s Michael Mann films at the time. They don’t use those kinds of fonts, [but] something about the style, it was like a little bit 80s genre.

And I wanted to stylise the film like that at the start, so you would know that it’s not a realist film, and it has an element of genre, but it’s playing with the genre. And then I love that blue colour. The slight 80s genre influence, which is very indirect, [in that] we use a zoom lens. I just had a great fun having a zoom lens in the film. It was an actual 80s zoom lens, and that creates that feel that is a little bit out of time. I think I wanted to create that juncture in the film between realism and genre, which is really at the heart of the themes of the film, reality and imagination and art and life and the thing that repeats itself in various aspects of the film. To open with a very contemplative, naturalistic landscape, and then to have a stylised font just seemed really fun to me.

I love how it calls attention to itself. A lot of the elements of the film calls attention to itself, and then [they] force you to consider [them]. The sound, for example, I was so conscious of the sound being recorded. It’s interesting you mention De Palma because I got that feeling of Blow Out, where we’re being made aware of what sound does to us, and how we pay attention to sound and especially choosing what sound to actually put in there. How did you write the sound design in the script?

AL: I was lucky enough to work with a really great sound recordist. I think that the sound was a big part of the script, because I remember even when Steve Bond, the sound recordist, read the script, he was like, “This is gonna be really fun for me.” And I was like, “Yes, I’m glad you say that.” Especially in that opening scene when it’s playing with the subjective and objective sound. And then also, I’m very fortunate to work with Livia Ruzic who’s the sound designer who did Strange Colours, and she did some of my short films as well. She’s an iconic Australian sound designer. And our mixer Keith [Thomas]. They’re just a great team.

On set and in post I just had a really great sound team. It was so exciting because I wanted to create a world that was a little bit dissonant and I think that the sound really helps because it kind of enters your experience as a viewer on a different, like on a sometimes unconscious level, but it can make you feel the scene in a really powerful, profound way.

And we had also a really great challenge with the sound on set because, of course, this might sound naive, but because I always think that “It’ll be fine,”, but it’s really, really difficult to shoot a film in the city. And this is something I guess I didn’t think about after Strange Colours because Strange Colours was such a dream because we’re in the middle of nowhere in any way. The only problem we had was like gennie [generator] going somewhere in the background that was noisy, and we’d have to go ask them to turn it off. But that was basically it. In Melbourne, it’s like impossible. There’s so much sound interference. It was so hard. We lost time having to pause because there’s always some construction, something happening. Recording sound by the water is rough. The scene in Port Melbourne, that was a nightmare to record sound because there’s traffic, water, it was really windy in the winter.

But somehow Steve managed to record sound, it’s a question for him how he pulls it off. And then also in post-production, they created something really special. With Livia, she’s got this amazing library of sounds that she uses. And we always try to pull authentic sounds from places and create the real feeling of a place with familiar sounds. Those little sounds like the beep at the traffic crossing, or particular Melbourne winds, I think they have a particular sound, and birds from the place.

It was something in a script, and I talked to everyone about it, even in pre-production that I really wanted the sounds of construction and that sound of a progressive city to be a real part of the film; airplanes, a lot of construction, traffic. The sound kind of has this slightly dirty feel. And that again partially plays with inducing that kind of anxiety even though you don’t see anything particularly menacing, but there’s a sense of anxiety, which is part of living in the city. Then it’s true to living in the city, especially when you start recording sound, you just realise how noisy and oppressive the sound is. And then playing with a genre because a lot of elements, a lot of sounds of construction and airplanes actually sound like sounds from horror films, those kinds of industrial bones that we know from industrial music or noise music.

I was really interested in how that could enter a film that’s not that and yet play with you on a different level. So that was really fun and interesting.

Let’s talk about the cinematography. You’re working with the great Michael Latham and who is in my opinion one of the best cinematographers working in Australia right now. He manages to make the screen feel so organic and lived in. What did you shoot on, and what’s it like working with Michael as well?

AL: Yes, I’m very lucky to work with Michael. It was very exciting. He shoots on an ARRI Alexa, but with older lenses. When we started the conversation, I was like, “I want to use a zoom lens,” and he was like, “Okay”, and then like he ordered this really cool 80s lens, and he was like “I’m pretty sure Tarkovsky would have shot on this.” Not that exact one, but that kind of lens. That was a really exciting thing. And it’s still in my bedroom lying somewhere because at the end, he was like, “I’m probably never gonna use this again, it’s really heavy.”

It was a real challenge to work with that lens, because it’s not very fast, so you have to use a lot of light. And neither of us had worked with this lens before, so there was a lot of figuring things out on a practical level. I had to think ahead about what lens I wanted to use, and if we were going to use the zoom, also obviously, we were using primes [a fixed focal length lens], but if we were to go on zoom, it would be a whole new lighting setup, which would chew up time and it was just hard to know ahead.

I think all that really contributed to this slightly magical feel of the film. It’s something that I talked to him about how to create. I wanted the film to be really romantic, and the universe to be really romantic, even though it’s sort of urban and the life that’s portrayed is quite melancholy, and hard. And the kind of industrial sounds we just talked about, and that feeling of the city, but I wanted it to be beautiful and romantic and noirish in the way that Melbourne comes across. It was a real obsession of mine to create that on screen.

Michael went out and found the filters and little tricks that he used to create that kind of softness, that kind of effect of being soft around the edges you see more of that on film, and it’s really kind of hard to create that on a digital camera. Cj Dobson, who graded the film, also worked to create that look, to draw that look out, and they did a really marvellous job.

Something I think that’s interesting with Michael, and on this film, you really see it, [is] he’s not afraid to expose a scene like maybe any other commercial cinematographer would do. There’s a sense of darkness, and it’s always kind of on the edge of what’s acceptable exposure. And I think it’s really bold and cool. I guess you the traditional thing to do would be like, let’s over expose it, and then expose it really well, because then you can grade it down. The film is really shadowy, it’s like this world of shadows, and shadow play, and you can’t really always make out what you’re seeing. And Michael wasn’t afraid of that. And sometimes like in the scene in Flagstaff gardens, for instance, in the park at night, we barely had lights, he was just shooting with the what was there in the park.

There is some beautiful dialogue here that sways between the realism and the fantasy that I just find is so really beautifully written, the two main characters are really beautifully written as well. There’s a line which I’ve written down, which is “I fall in love all the time. It’s just not with a real person.” Which I think is so glorious. Reading into it with the view of an artist and their art, and especially as somebody who watches and consumes films, art and books, and it feels like each one that I fall in love with is, again, it’s not a real person, it’s a film or it’s a book, but that’s what I’m doing, that’s my relationship [with it]. Is that kind of what you were aiming for?

AL: I think that’s really wonderful observation and quite acute. And I didn’t even really think about that particular line, because it was just felt organic to that conversation that they were having. But I think that it does capture something about those themes we were just talking about, art and life, reality and imagination, and the kind of line at the edge of reality. And I think that a lot of the melancholy in the film comes from this.

Some people have asked, “Is Mia real?” And, to me, she’s definitely real. I guess the feeling of unreality comes from, to me, something that’s really part of just any relationship or being a person to start with, which is that you can’t quite ever have a full grasp of reality. Just like those ancient philosophical problems, you don’t really know what’s outside of you, and you’re very limited in your perception. And there’s a kind of melancholy in realising that even the people you get really close to, you can’t really know anyone completely. But especially in the relationship that’s explored the film, it’s really messy, because so much of what you know about the other person is just you. [It] is your own imagination, or what you imagined about them. And I think that’s really common, it’s kind of the core of human relationships.

As you say, that relates to art and falling in love with art, which is such a big part of their bond in that world and being in this world of ideas and images and beauty and aesthetics and talking about those things. They are both artistic, romantic people who are very prone to getting confused. So, I think that’s kind of what the film is really about, actually. That line of where you end and something else begins, that’s very hard to grasp. And that’s at the root of all the confusion and disorientation in the film in general, and the style of the film and the dialogue of the film.

It’s something I’m going to be mulling over for a long, long time, just like I do with Strange Colours. Your films are so thematically rich, it’s quite brilliant to revisit them when you’ve let them sit in your mind for so long.

Last question, what does it mean to be an Australian filmmaker working today? Strange Colours was such an intimately Australian story, and this one is very Melbournian. I’m curious for you, is that something that you’re interested in exploring as a filmmaker?

AL: Australian cinema is always shaping, I feel like it’s probably fair to say that in this country we’ve never had a strong cinematic identity. We have a lot of brilliant filmmakers and even little pockets of movements, but nothing like Italian neo-realism or something like this. It’s kind of more sporadic and dispersed. And now I think there’s a great thirst to create something.

I’m really excited to go back to Melbourne and try and catch some of the Melbourne on Film program, which looks really brilliant. That’s really exciting that that’s happening this year when my film is coming out that is so Melbourne. Also, there’s so many great Australian films in the program. I’m also really looking forward to seeing The Plains by David Easteal. And Thomas’s film [The Stranger], which I also haven’t seen the final cut off. And, there’s so many I’m gonna leave many out.

James’s Friends and Strangers which came out last year, James is a really good friend of mine, so it feels like we all kind of know each other and have conversations about film. So it feels like something. And I think that, these are all really different films, and even different genres and completely different styles, but I think that what unites us is that we all want to do something – I don’t know how to put it politely – that appeals to the rest of the world. Maybe there’s a feeling that Australian cinema has been a little bit insular [since] when I’ve been coming of age as a filmmaker. And we all want to be part of the global conversation about culture. And so I think that we’re all drawing influences from Europe and Asian cinema or whatever. Everyone has their own things to say about it, but I think that unites us that there’s this thirst to create something that will be shown at festivals around the world and will be interesting, but at the same time, be very Australian.