John Michael McDonagh, director of the superb drama Calvary, returns to his themes of hypocrisy and excess in his latest and most expensive feature, The Forgiven. Set in Morocco instead of his native Ireland, McDonagh with the excellent eye of cinematographer Larry Smith crafts a visually sumptuous piece that unfortunately too often relies on exaggeration to adequately convey complexity.

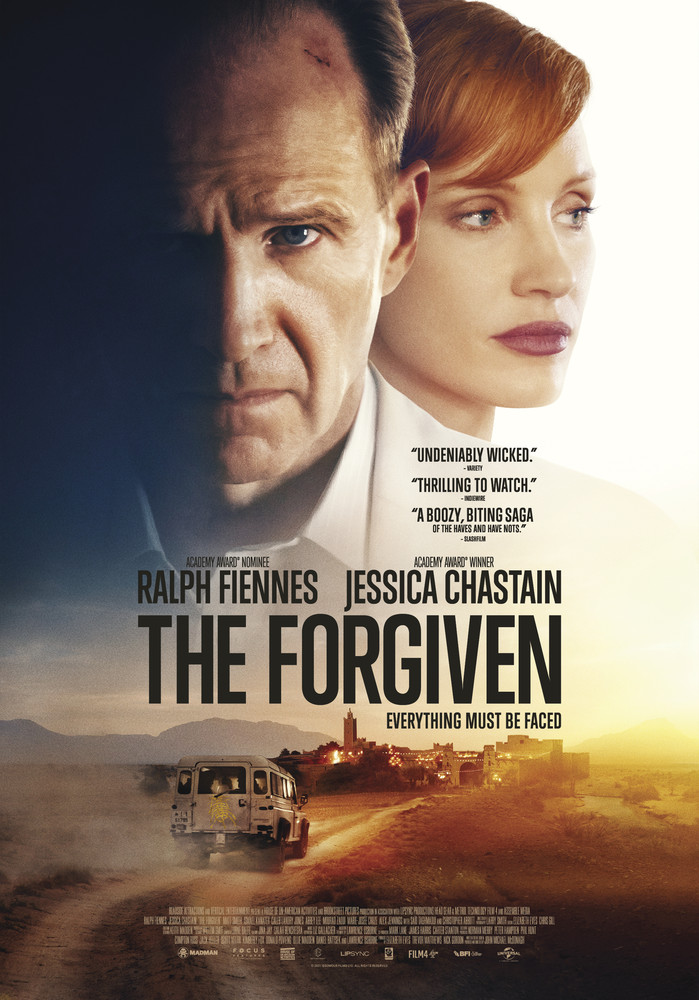

Adapted from Lawrence Osborne’s novel and written for the screen by McDonagh The Forgiven begins with a wealthy couple in Tangier who are vacationing from London to attend the house party of an even wealthier gay couple. David Henninger (Ralph Fiennes) and his American wife Jo (Jessica Chastain) are unhappily married but seem settled into their routine of barbed insults and deep cuts. David, a doctor, is an alcoholic with a distaste for almost everyone. He is callously racist, homophobic, and misogynist which leads to Jo appearing to be the more progressive of the two as she suffers embarrassment at her husband’s crassness.

Driving from Tangier to a grand estate owned by David’s ex school chum, Richard “Dicky” Galloway (Matt Smith) and his partner Dally Margolis (Caleb Landry Jones) in the Atlas Mountains, the drunken David hits and kills a local boy, Driss (Omar Ghaaoui) who was attempting to sell the couple a fossil. Not knowing what to do the couple bundle the body of the dead boy into the backseat of their rented car and continue on to the party.

Jo appears to be in genuine shock at what has transpired, and David seems mostly annoyed by the inconvenience of it. A pragmatic Dicky calls the local police and assures the couple that they’ll probably have to pay something to make it all disappear but it’s unlikely that the investigation will be taken much further. Morocco is a place where “people vanish.” What upsets Dicky most is that the police will not be able to remove the body of the boy during his weekend festivities and having a corpse around will perhaps dull the tenor of the wildly extravagant weekend.

The next day Driss’ father Abdellah (Ismael Kanter) arrives to collect the body. He insists through his translator Anouar (Saïd Taghmoui) that David accompanies them back to his home village to bury the boy and pay for what he has done – presumably with financial restitution. David’s initial reaction is to protest that as far as he knows these people could be “fucking ISIS,” but is convinced by Dicky that it would be a far easier way to deal with the situation instead of involving the embassy who would conduct a thorough investigation which would not be in David’s best interests.

At this juncture the narrative splits its focus to following David and Abdellah south to his home and remaining with Jo and the partygoers at Dicky’s residence. A deliberate object lesson in contrasts could not appear more contrived. As David is driven through increasingly abject poverty, Jo takes to imbibing the party spirit (in more ways than one) finally free of her dreary husband.

Dicky’s party, and indeed all of his guests, are emblematic of the overindulgences of Westerners as they callowly dismiss their part in colonising a poor country that has been at the mercy of Europeans for years. From a conceited over-the-hill and hard partying Lord (Alex Jennings) to a hypocritical French journalist (Marie-Josée Croze), to a vapid party girl (Abbey Lee) these characters are the epitome of careless people (to quote Fitzgerald). The group are repugnant narcissists who casually discuss Islamophobia in front of the long-suffering staff without ever admitting to their part in creating and fostering such a huge cultural divide, all the while snorting enough cocaine to the cost of which would feed a local village for a year.

Ostensibly less obnoxious is American business analyst Tom Day who strikes up a flirtation with Jo. He’s aware that he’s in a country that favours his wealth and privilege. His interest in Jo is clearly motivated by his wish to have sex with her but that idea is embraced by the bored wife rather than rebuffed. As the weekend transpires the audience is invited to watch the veneer of civility peel away from Jo who we learn is as resentful, self-absorbed, and as indifferent to the suffering of others as her husband appeared to be.

Meanwhile, David’s trip to the home of Abdellah and Driss opens his eyes to how casually he has become inured to people’s pain. Incrementally he begins to understand that his life has existed without real grief and hardship. Abdellah, played with gravity and subtlety by Kanter is both terrifying and pitiful. Abdellah is a man who is overcome with the loss of his only son to a system of inequity personified by David. Finally understanding his surroundings and the part he has played in destroying lives, David seeks redemption and is resigned that it may cost his life.

Observing a couple like the Henningers effectively swap moral spaces with each other is what McDonagh hinges his film upon. However, there is so much more to say about the social issues that the work depends on. Inserting acerbic dark comedy into the mix, whilst superficially entertaining, does little to address what plagues post-colonial nations like Morocco. It’s not just the scarcity of resources nor the tourist driven economy that fuels the region’s slow decline. There is more to be said than “Rich people are arseholes who don’t care about other people,” we already know that.

Where the film succeeds is in some of the slighter blink-and-you’ll-miss it sections. Dally insists that he has costumed the servants “authentically.” David bemoans the prediction for people he sees as uncultured to believe in ritualistic symbols. Jo complains that she hasn’t been served honey with her tea. A revered auteur filmmaker (played by Imane El Mechrafi) is making a film about North African Nomads yet is happily ensconced in the hedonistic milieu of Dicky, Dally, and their hangers on. Anouar explains to David that a fossil that is being excavated to be turned into a coffee table for some wealthy European is all that the desert has to offer in terms of survival for its inhabitants. If McDonagh had limited himself to making his point with these more subtle set pieces the film would have avoided repeating itself so often that the sledgehammer effect dulls the messaging.

Matt Smith, Ralph Fiennes, and Jessica Chastain give admirable performances. Embodying people who move between sympathetic and despisable isn’t an easy job yet all three manage it. Smith is wonderfully loathsome as the scathing and clever Dicky. Yet of all the people in the film, Dicky is the most authentic – he is unapologetic for everything from his wealth to his lifestyle. Fiennes manages to convince as a man who has become unmoored from his humanity. It is Ismael Kanter’s potent supporting turn as Abdellah that gives the story a sense of dignity that is lacking in other areas and is admirably bolstered by Saïd Taghmoui as Anouar to imbue the characters with a humanism that is missing generally in the film.

Although not a failure The Forgiven is a little too thin to be the type of film that it sets out to be. It’s nasty, but not nasty enough, it’s tense, but the tension wanes due to the over reliance on demonstrating a gulf of privilege we already know is there. After McDonagh’s superlative character work and atmosphere in Calvary, The Forgiven appears to be a step down in the director’s ability to capture moral conundrums and how they impact upon the communities in which they occur.

Director: John Michael McDonagh

Cast: Ralph Fiennes, Jessica Chastain, Saïd Taghmoui

Writer: John Michael McDonagh (adapted from novel by Lawrence Osborne)